In the first part of the 2026 outlook, the focus was on the overall macro mood and how AI is starting to change the physical economy. The next part zooms out and looks at how kthe world is adjusting underneath—how trade is being rerouted, why governments are running bigger deficits, and why different regions are starting to look less alike.

Trade isn’t dying, but it’s being rewired

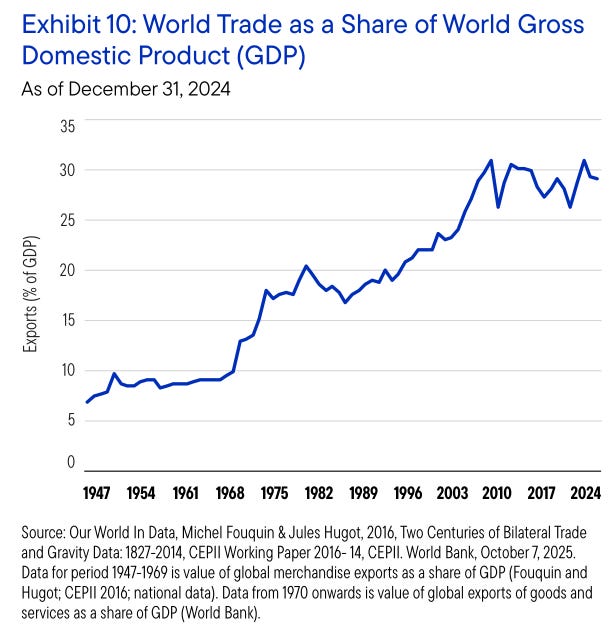

If you only look at the headlines, it feels like globalization is going backwards. Tariffs are rising, trade wars are back, and every country wants products stamped “Made in X.” But when you look through the big global outlook reports, they’re all saying something slightly different. Trade isn’t falling apart. It’s changing how it works.

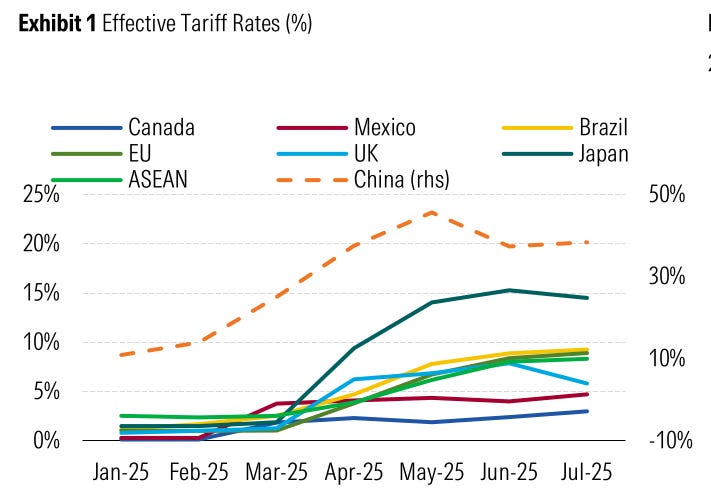

Morningstar’s outlook captures this mood by calling the moment “Global Trade in Turmoil.” US tariffs are clearly higher than they were before 2018. But for most major trading partners, they still sit below 10%. That’s a real shift, but it’s a long way from the kind of shutdown the world saw in the 1930s. The bigger change isn’t how high tariffs are. It’s where their impact is showing up.

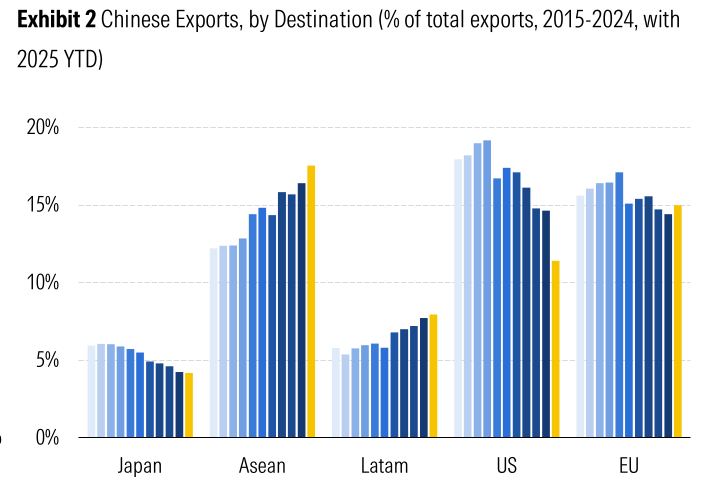

The clearest break is in trade between the US and China. A few years ago, the US took nearly one-fifth of China’s exports. That share has steadily fallen—from around 18–19% in 2017–18 to about 14–15% in 2024, and closer to 11–12% in 2025.

But that trade hasn’t disappeared. It’s been redirected.

Southeast Asia has absorbed a large part of it. The share of ASEAN countries has risen from roughly 12–13% in 2015 to around 17–18% today, making the region China’s largest export destination. Latin America has also taken a bigger share, climbing from about 5–6% to nearly 8%. Europe, meanwhile, has stayed broadly stable. In simple terms, the US–China trade route is narrowing, but China is still exporting at scale—just through different paths.

Goldman Sachs helps put numbers around this shift. In their 2026 Outlook, they estimate that US tariffs now amount to about 18%, the highest burden on American consumers since 1934. Even so, they don’t expect global trade to collapse. Companies have adjusted instead. They’ve shifted supply chains, sourced from more places, and raised prices where possible. So far, many have managed to protect margins despite the policy swings.

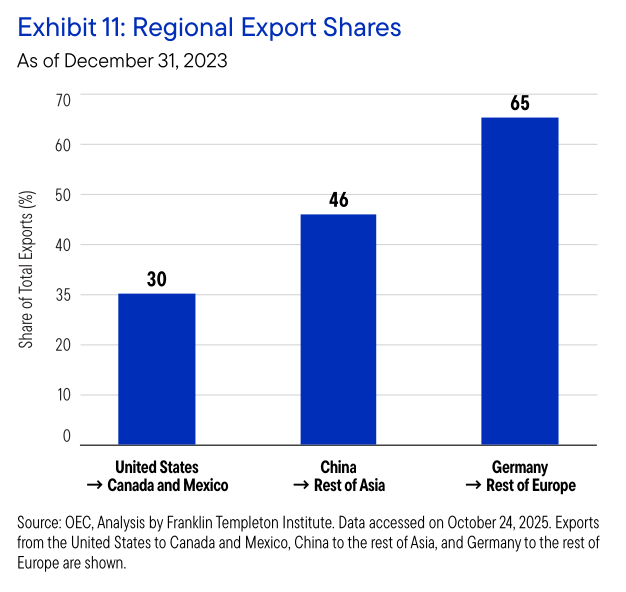

When you step back, these company-level moves start to add up to something bigger. As Franklin Templeton argues, globalization isn’t ending so much as being reorganized.

The old idea of one tightly connected global market is fading. In its place, a more political and more regional system is taking shape, built around three broad blocs: North America, Europe, and Asia.

Other reports describe the same shift in different ways. JPMorgan calls it a move from globalization to fragmentation, driven by tariffs, technology controls, and geopolitics. Goldman talks about a new trade order, where companies worry less about being the cheapest and more about keeping supply chains secure.

One data point ties this together. Global trade, as a share of the world economy, has barely grown since 2009. But investment into supply chains has surged.

Regions are rebuilding how things are made and moved—from North America’s push to manufacture closer to home to the fast-growing China–ASEAN–India corridor.

S&P’s data shows China sending far more goods to the Global South than it did a decade ago, strengthening trade within Asia itself. Europe, meanwhile, is feeling squeezed, caught between cheaper Chinese imports and rising protectionism at home.

This new regional order doesn’t benefit everyone equally. Countries like Mexico, Vietnam, Indonesia, and India are emerging as clear winners from this rewiring. At the same time, many Asian manufacturers face tougher competition as Chinese goods are redirected into their markets. And despite all the talk of decoupling, a clean break remains unlikely. The US still depends on allies for minerals and processing, while China’s grip on rare earths keeps both sides tied together.

Big government and the fiscal overhang

On fiscal policy, the reports are surprisingly aligned. Governments are bigger, deficits are wider, and this isn’t something that’s going to reverse anytime soon.

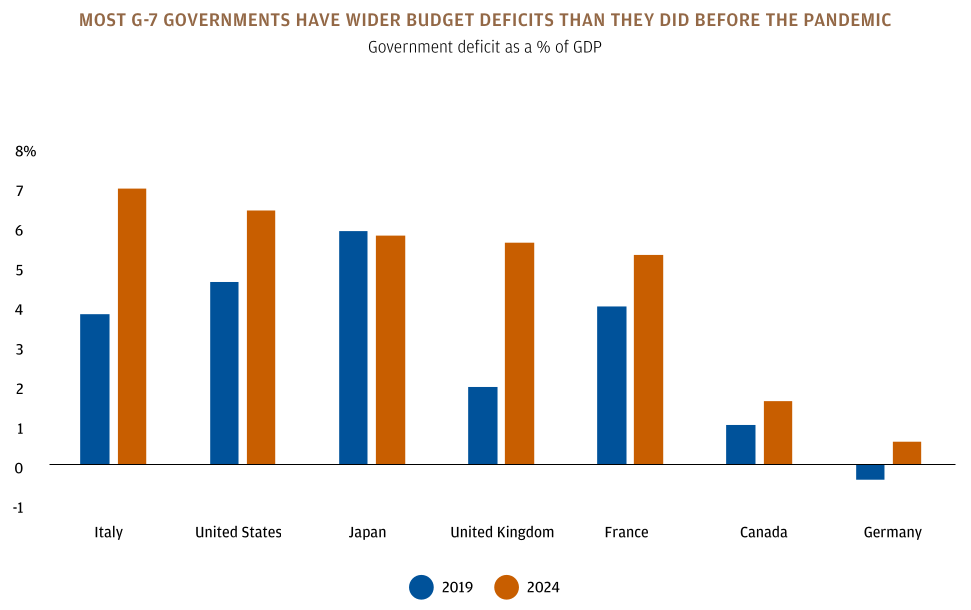

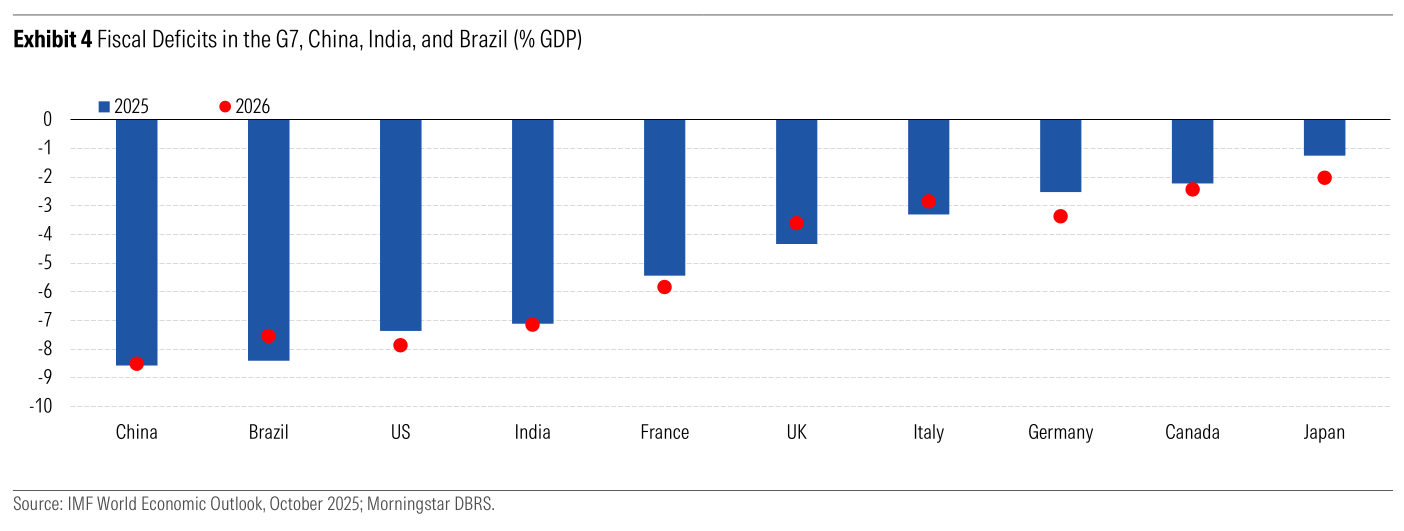

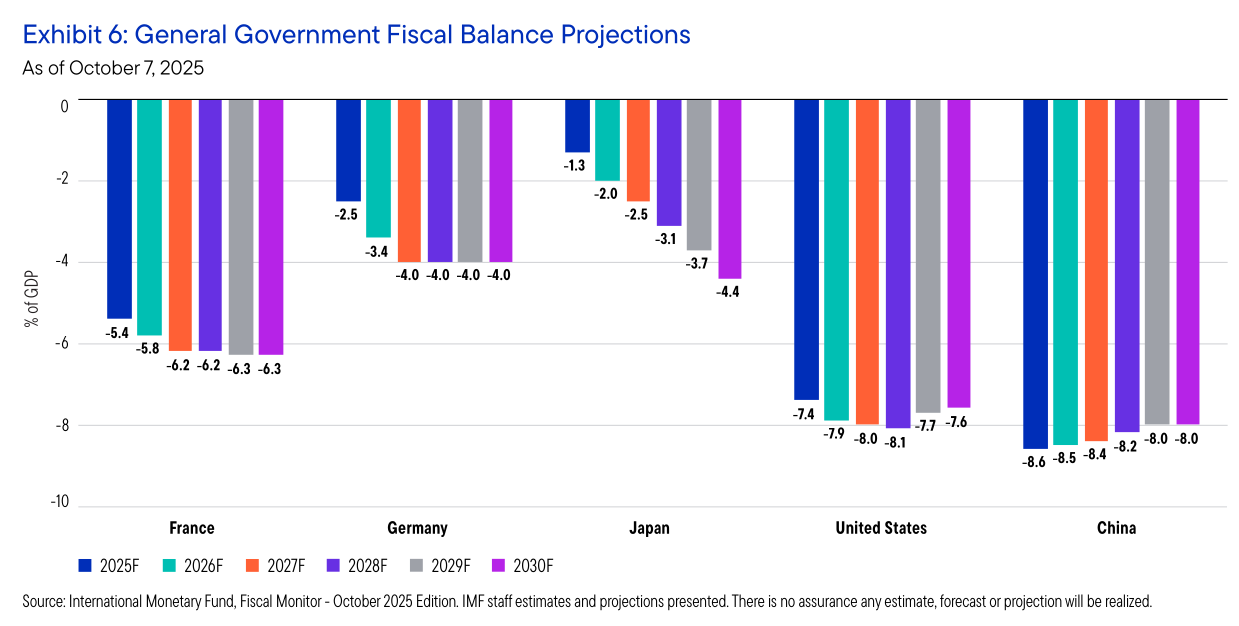

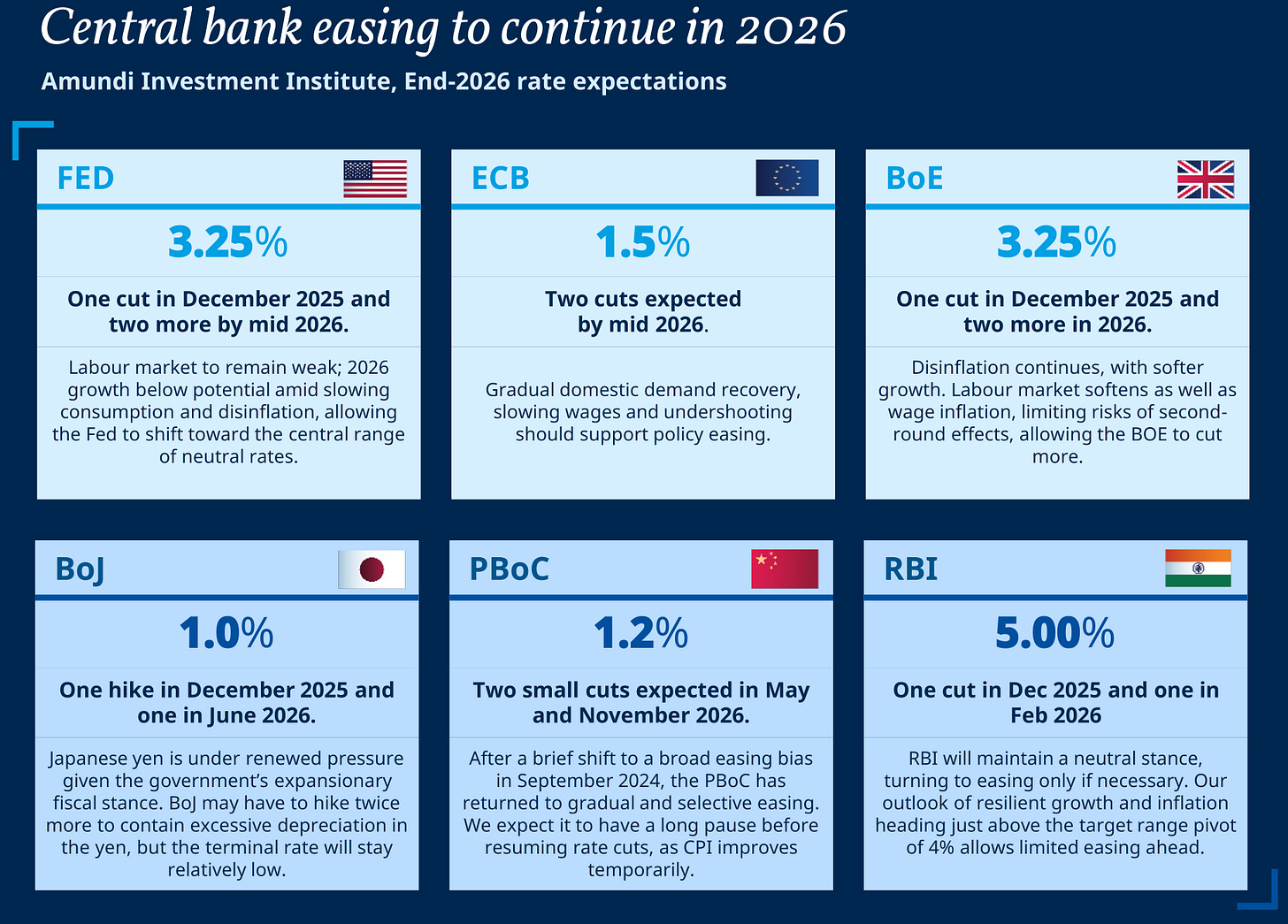

Government finances are already stretched in most big economies, and many are likely to get worse in 2026. As per Morningstar, budget deficits across the G7, China, India, and Brazil are staying firmly in the red through 2025 and 2026. The reasons are well known, but they’re all hitting at the same time: slower long-term growth, aging populations that push up pension and healthcare costs, higher welfare spending, bigger defense budgets, and rising interest bills as old debt is refinanced at higher rates.

Weak public finances are becoming one of the biggest risks to sovereign credit ratings, not just in rich countries but also in large emerging markets like China, India, and Brazil.

What makes this period different is that these deficits aren’t being driven by a crisis. Many governments are running large, persistent budget gaps even though unemployment is low and growth is reasonably stable. That leaves much less room to respond when the next slowdown eventually comes. It also means bond markets start worrying about fiscal risks much earlier than they used to.

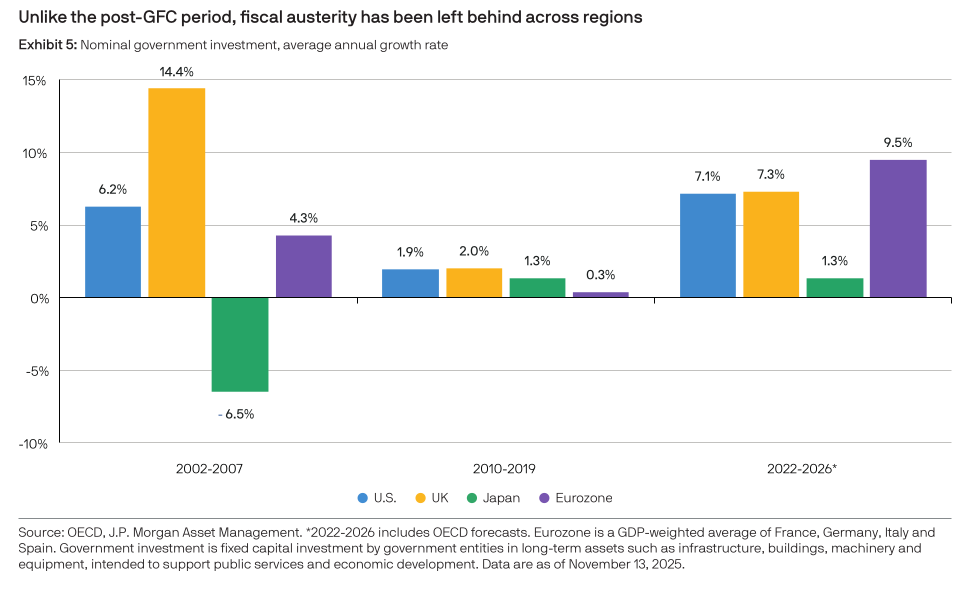

Franklin Templeton describes this shift as the start of an “era of big government,” as we touched on in part 1. The old belief in small government, tight budgets, and strict discipline has been fading ever since the global financial crisis. Today, governments are playing a much bigger role in trade policy, industrial strategy, defense, the energy transition, and social support. Their charts show large and ongoing deficits across the US, Western Europe, China, and possibly Japan, with only a small group of emerging markets moving the other way.

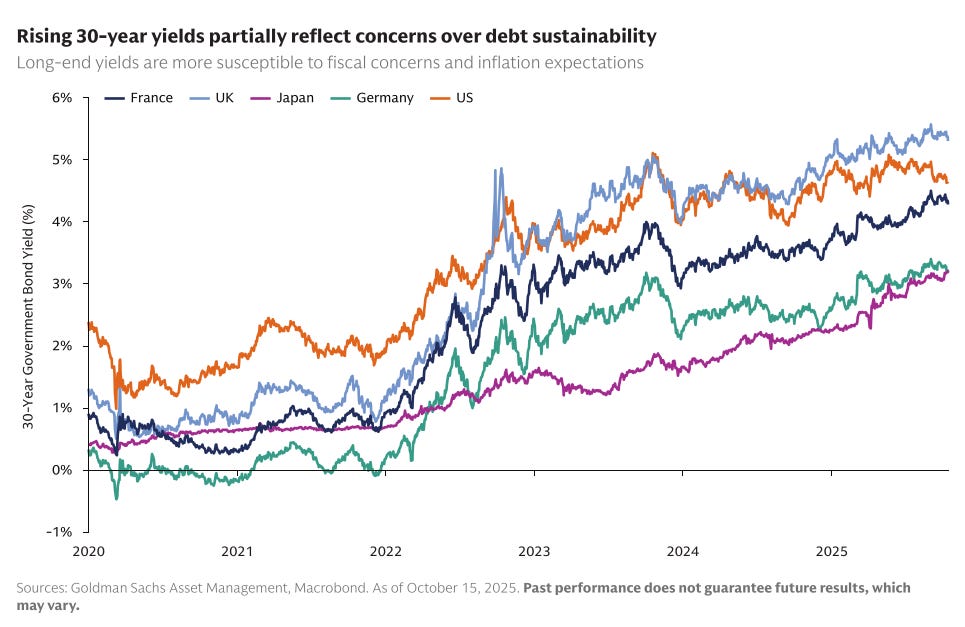

Goldman Sachs adds some perspective on scale and market reaction. Global government debt has now crossed $100 trillion. In the US, deficits are unusually large given how strong the economy still is, with debt levels close to post-war highs. Goldman also points to France as a warning sign. Political uncertainty there has pushed 10-year bond yields close to Italian levels, showing how quickly markets can lose patience when fiscal worries meet political instability.

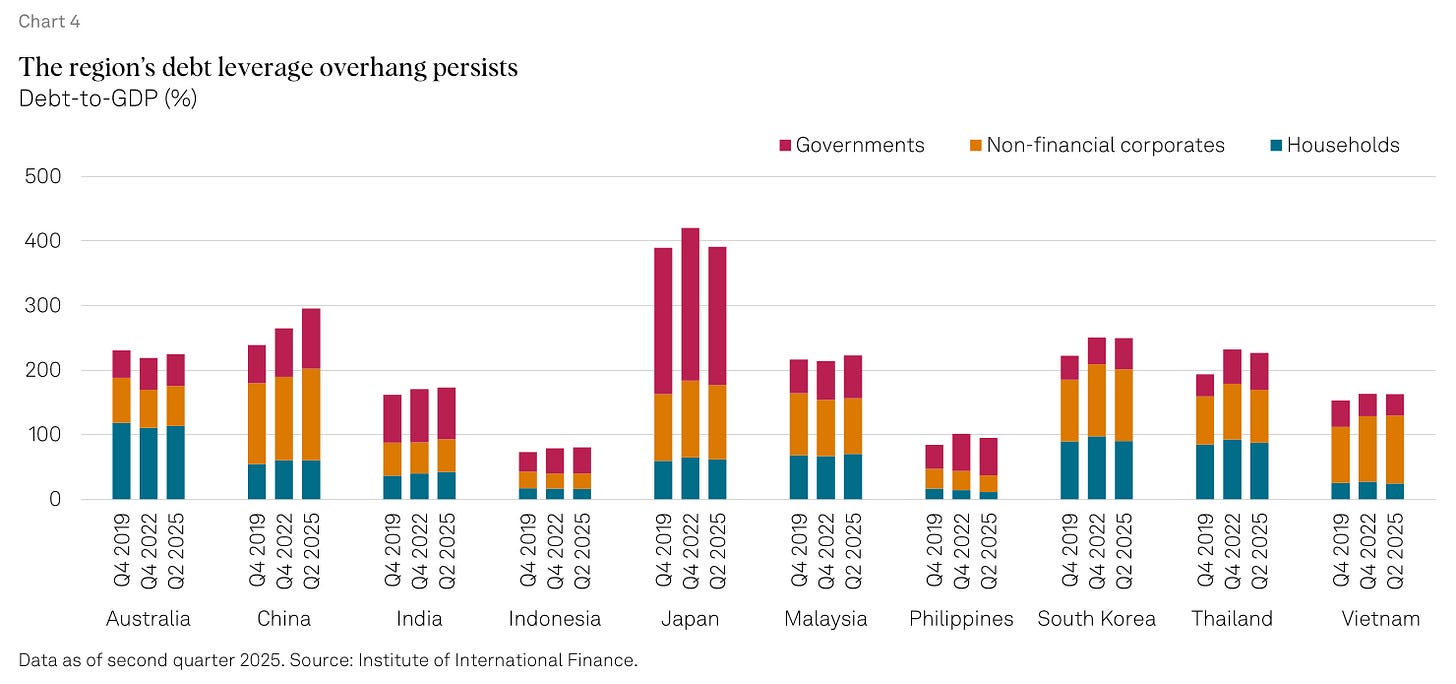

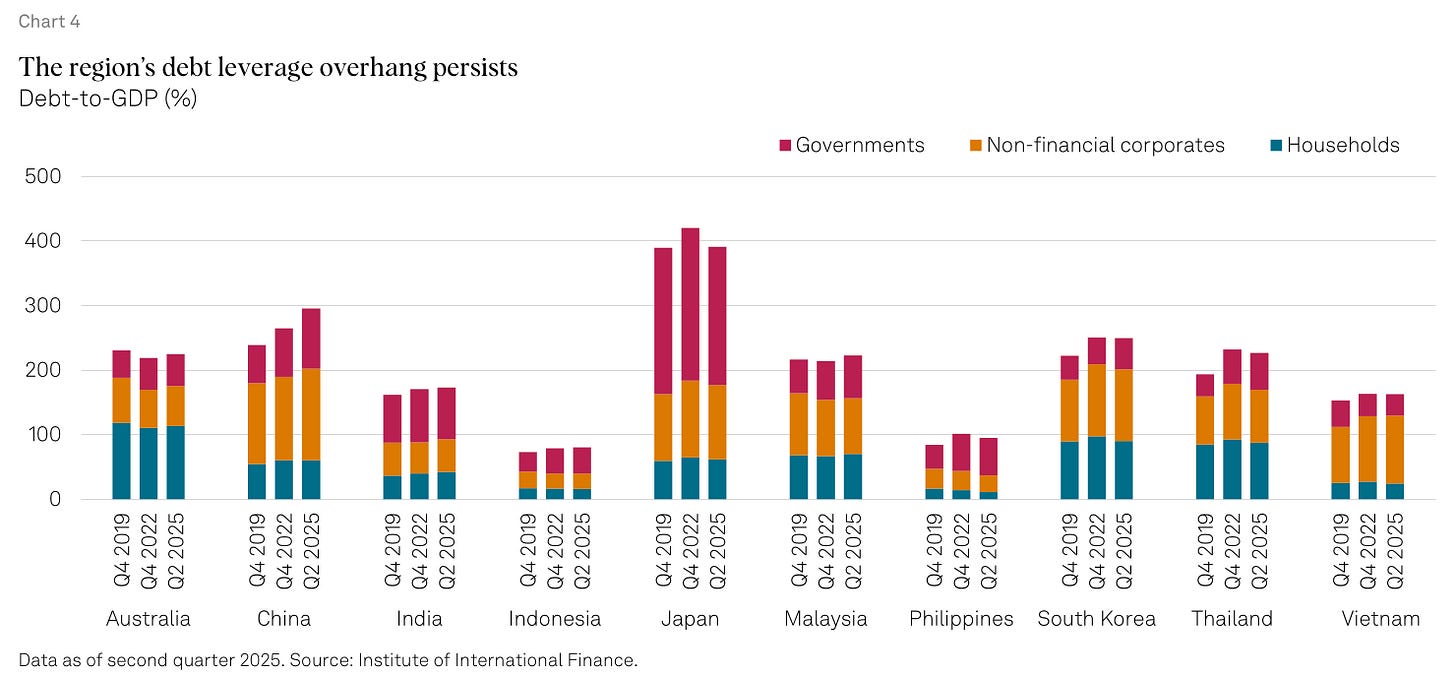

S&P’s Asia-Pacific outlook tells a similar story. Many governments in the region have taken on much more debt since 2019. S&P warns that efforts to cut deficits may stall, as governments lean on spending to deal with high living costs, social pressure, and uneven growth—even if that weakens their balance sheets further.

One important consequence is competition for money. When governments run large and lasting deficits, they compete directly with the private sector for savings. That includes investment in AI, data centers, energy infrastructure, and the climate transition. This makes it harder for interest rates to fall in a meaningful way. Higher real interest rates start to look less like a short-term phase and more like something that could last through the decade. And that raises the bar for returns across markets while putting pressure on valuations if profits don’t grow fast enough.

Markets are also becoming more selective. Not all deficits are treated the same anymore. Countries that issue reserve currencies, like the US, still have more breathing room. But even there, long-term bond yields are reacting more quickly to fiscal news. In countries without that privilege—from parts of Europe to large emerging markets—loose budgets are translating much faster into higher borrowing costs and pressure on credit ratings.

As deficits stay large, central banks face more pressure to support government borrowing. That makes it harder to keep monetary policy fully independent. Inflation control becomes more political, and bond markets become more sensitive to elections, budgets, and policy surprises.

Put simply, three things are happening at once. Governments are spending more—on defense, energy transition, social support, and industrial policy. There’s little political appetite to reverse that. And the cost shows up as higher debt, more nervous bond markets, and bigger swings in long-term yields, especially around elections and budget announcements.

What else do the reports warn about

Beyond the big headlines, there’s a set of slower-moving forces that don’t always make it into the executive summary.

China: slowing down, not falling apart

Most reports don’t see China as heading into a crisis. They see it in the middle of a long transition. S&P describes China as slowly moving away from an economy driven by property and heavy borrowing and toward a more mature model by 2035. The focus is shifting to areas like advanced manufacturing, green technology, and other strategic industries.

This shift isn’t painless. S&P is clear that there will be losers along the way. Some companies—including state-owned firms—and weaker banks are likely to take losses as excess capacity is worked out of the system. The cleanup in real estate is still unfinished.

Local governments are under financial strain. Private investment hasn’t fully recovered. Slower growth, in this sense, is not a mistake. It reflects a choice by policymakers to accept short-term pain in order to create a more stable system over time.

Policy support has also changed. Instead of big, economy-wide stimulus packages, China is using smaller and more targeted tools. Support is being directed toward specific sectors, with selective liquidity help where needed. This makes a sudden collapse less likely, but it also caps how fast the economy can grow. Growth is being guided carefully, not pushed aggressively.

Most of the pressure is now inside the country. Local governments are struggling with weaker land-sale income and rising spending needs. Banks are dealing with stressed loans without assuming they’ll always be rescued. Investors, both at home and abroad, are adjusting to lower returns and more policy uncertainty. The real question isn’t whether China slows—that’s already happening. It’s how the costs of that slowdown are shared across the system.

The main risk, then, isn’t a sharp crash. It’s a long period of repair, where losses are absorbed gradually, and growth stays modest. How well China manages this phase will matter for years to come, even if there’s no dramatic crisis along the way.

Europe: holding up, but fragile

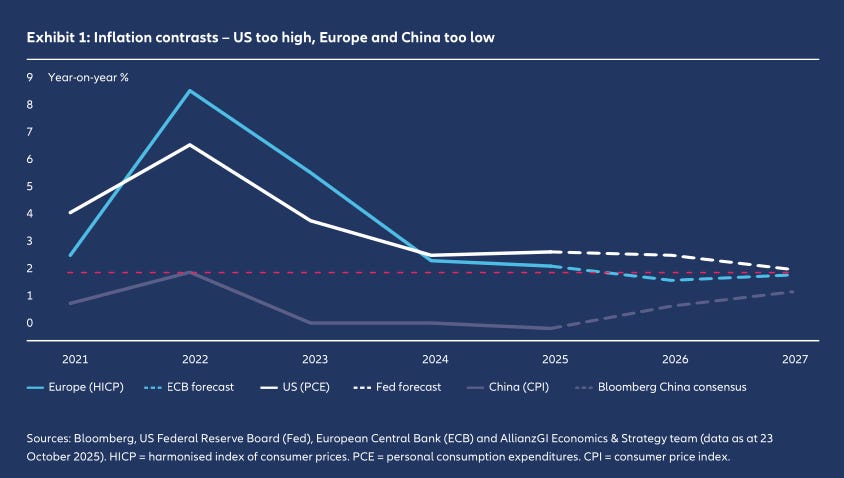

Most outlooks place Europe in an awkward middle spot. Growth isn’t strong, but it isn’t falling apart either. Amundi and Allianz describe an economy that’s being helped by higher spending on defense and clean energy but held back by tight budgets, weak productivity, and ongoing political uncertainty.

The bigger issue isn’t a lack of government support. It’s the absence of a strong private-sector growth engine. Years of underinvestment in technology, slow productivity gains, and an aging workforce mean that government spending mainly prevents things from getting worse, rather than pushing growth higher. Even defence spending takes time to show up in the economy, because contracts move slowly and capacity is limited.

T. Rowe Price flags a near-term risk. Many European exporters appear to have rushed goods to the US ahead of expected tariffs. That may have boosted recent data, but it could leave factories quieter in 2026. If that happens, the ECB may feel pressure to cut rates to support growth.

At the same time, higher government spending—especially in Germany—means more bond issuance. So even if short-term rates fall, long-term bond yields may stay high. Europe’s challenge isn’t avoiding a recession. It’s breaking out of a low-growth pattern where government support keeps the economy stable but can’t fully revive it.

Japan: a real change after decades

Japan stands out as one of the few clear changes in the global outlook. Morningstar notes that the Bank of Japan has started raising rates from extremely low levels, but policy is still loose by historical standards. More importantly, inflation has finally stayed above zero, ending decades of deflation.

The bigger change is in wages. T. Rowe Price expects labor shortages to keep pushing pay higher. This matters more than interest rates. Rising wages support household spending and reduce Japan’s reliance on exports to drive growth.

Policy changes are likely to stay cautious. With very high government debt, the BOJ can’t raise rates aggressively without upsetting the bond market. Any hikes are likely to be slow and careful.

The dollar and emerging markets

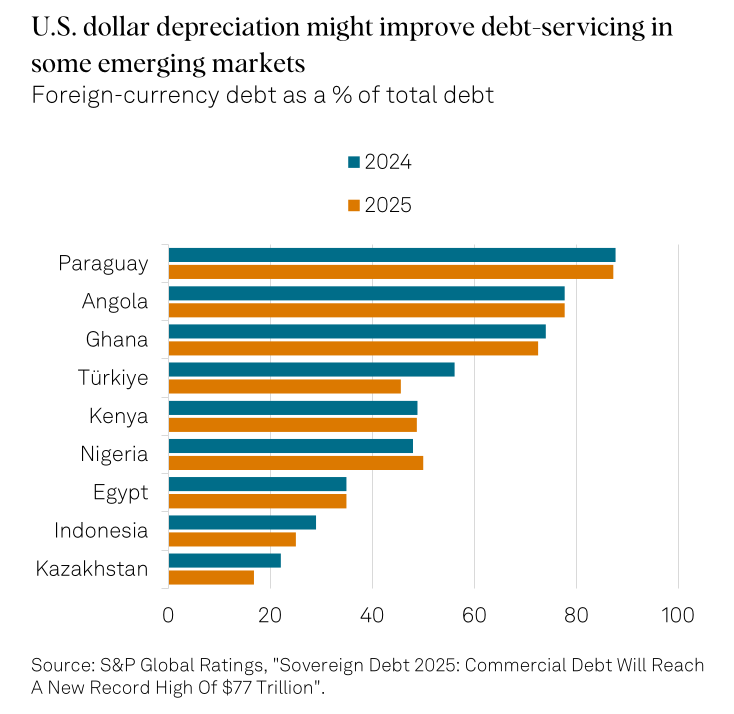

For emerging markets, the direction of the US dollar matters a lot. S&P shows that a weaker dollar can make it easier for countries to service debt that’s been borrowed in dollars. That alone can improve financial stability.

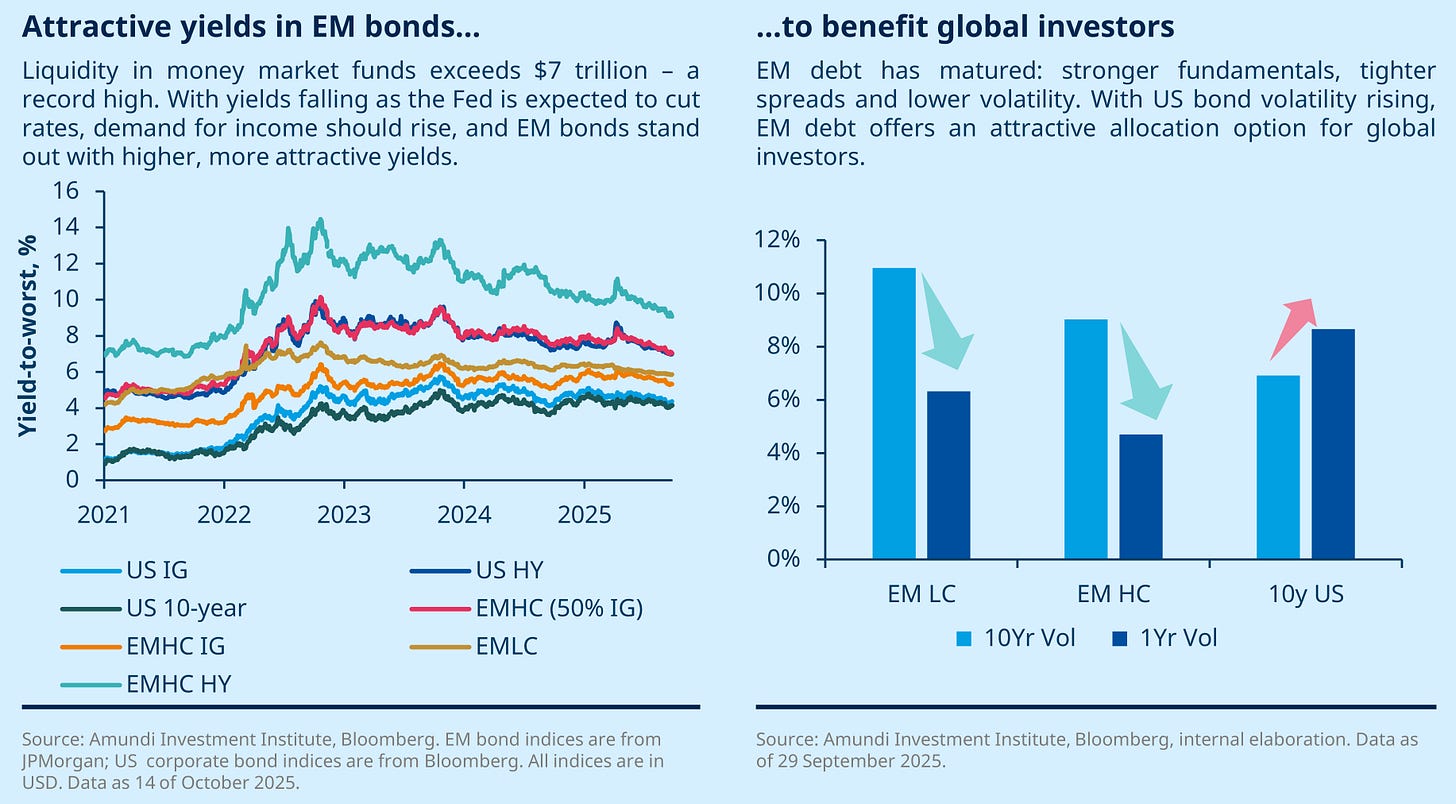

Allianz points out that many emerging markets, especially in Asia, are in better shape than in past cycles. Inflation is lower, interest rates are positive in real terms, debt maturities are longer, and more borrowing is done in local currencies. That makes them less vulnerable than during episodes like the 2013 taper tantrum.

Still, a weaker dollar isn’t a magic fix. Countries with weak public finances, unstable politics, or poor institutions remain exposed. The benefits will be uneven.

The likely outcome is divergence. Countries tied into global supply chains and technology investment look better placed than those relying mainly on commodities or loose fiscal policy. A softer dollar creates breathing room, but fundamentals still decide who can use it well.

Demographics: the slow force underneath everything

Demographics run quietly through almost every theme in the reports. Franklin Templeton and Morningstar both point to a widening gap between aging economies—like Europe, the US, Japan, and China—and younger ones such as India, Indonesia, the Philippines, and parts of Africa.

Aging affects much more than growth. Smaller workforces tighten labor markets, push wages up, and make inflation harder to control. At the same time, older populations raise pension and healthcare costs, adding pressure to government budgets.

Younger populations offer opportunity, but nothing is guaranteed. Franklin notes that demographic advantages only turn into growth when countries invest in education, infrastructure, and jobs. Without that, a young population can become a source of stress rather than strength.

Demographics don’t cause sudden shocks. But over time, they decide which economies keep moving forward—and which ones struggle to regain momentum.

That’s it for this edition. Thank you for reading. Do let us know your feedback in the comments.

Can someone please explain the stark difference in Japans Fiscal Deficit 2025 and Budget Deficit 2024? The two graphs shown up here in the article? All the other countries more or less match in the two graphs but Japan, Italy and UK.

Nice article indicating global uncertainty in different markets which depend on govt policies after fragmentation and tariffs. The South, South East and Far East and Central Asia have to necessarily unite with a common trading policy coupled with China. China would need to reforms its political and economic policies in tune with the requirements of these regions. Countries in African Continent need to understand their strength in a united scenario as a food and water security for the globe as well as for the continent's fast infrastructure and industrial growth . The African union needs to understand its prospect and have to have a uniform political and economic outlook . It is the next high growth continent