Welcome to Beyond The Charts. A series where we look at charts to make sense of what’s happening in finance and the economy and uncover the stories they tell.

The storm that never came has been the big story for the past few years. There were warnings of a recession in the US, an energy scare in Europe, worries about a hard landing in China, and a fight against inflation around the world, with no clear way out. As 2026 approaches, though, the world seems surprisingly stable.

As there’s quite a bit to unpack, in this and upcoming editions of Beyond The Charts, we’ll look at the outlook of big global financial firms like Goldman Sachs, Morningstar, J.P. Morgan, Franklin Templeton, Amundi, S&P, for 2026, and what it means for the rest of the world and India.

The best way to understand 2026 is to see that two themes are happening at the same time. One is that inflation is going down, interest rates are no longer going up, and the world economy has not gone into a deep recession.

But the other, more important one is how AI is changing the demand for energy and computing around the world. Political alignment is changing the way trade works. More money is going to defense, infrastructure, and industrial policy from governments. The need for climate transition is growing faster, and older people are changing the job market and public finances.

In this edition, we will take a look at the global macro outlook and AI.

The macro backdrop

Let’s begin with the big picture.

The first thing that Morningstar says in its 2026 outlook is that the global economy “weathered the trade policy-induced shock relatively well.” Their predictions say that growth in 2026 will be “reasonably strong,” with inflation falling in most advanced and emerging economies.

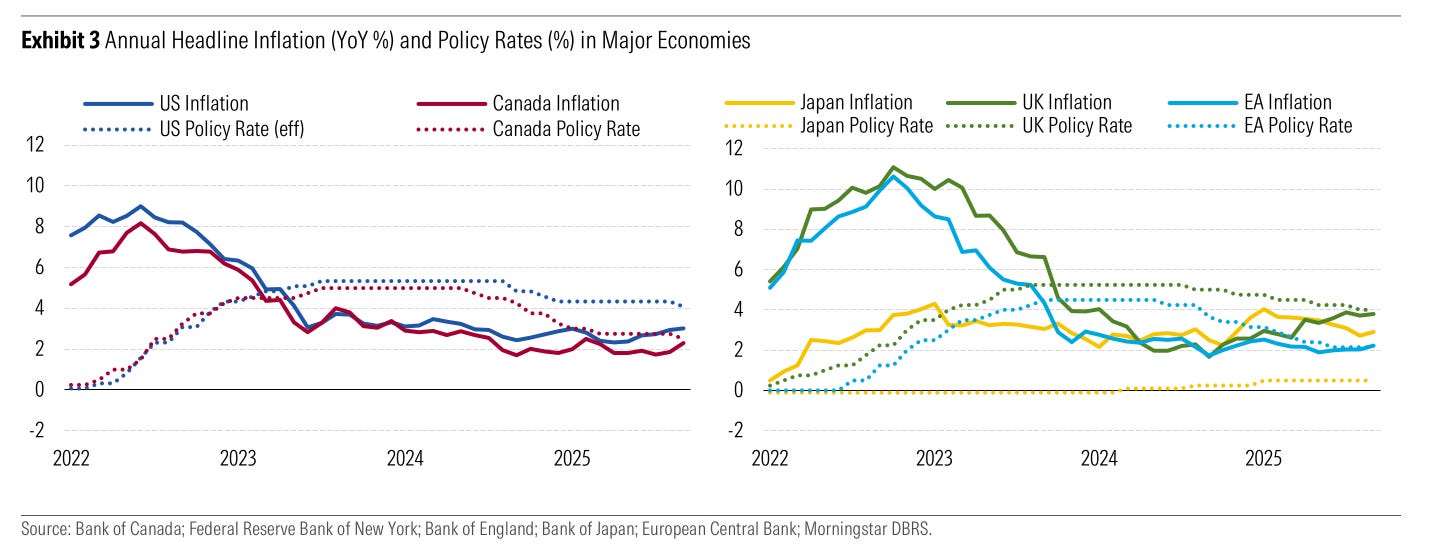

This chart from the report for the US, Euro Area, UK, and Japan shows these trends clearly. The rise in inflation since its peak in 2022 is behind us. The US and UK are still above their targets, but they are not at their highest points, and interest rates have begun to drop. Japan is the only country where the Bank of Japan is still raising rates from very low levels.

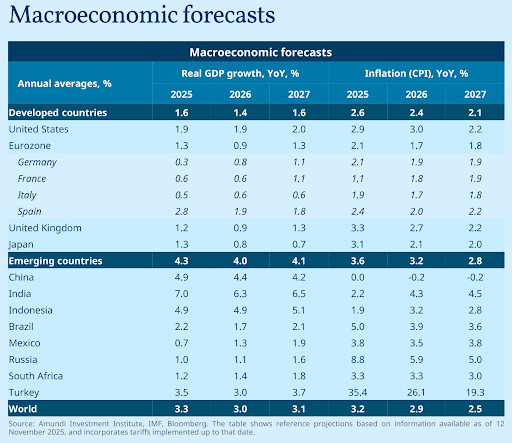

The numbers from Amundi for 2026 make it easier to see how inflation and growth are doing in the world’s biggest economies. They think that the US will grow by 1.9%, the Eurozone by 0.9%, Japan by 0.8%, China by 4.4%, and India by 6.3%. And the CPI inflation will be 3.0% in the US, 1.7% in the Eurozone, 2.1% in Japan, slightly negative in China (–0.2%), and 4.3% in India.

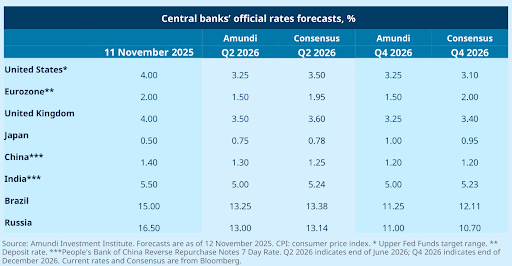

Amundi thinks that by the end of 2026, the Fed funds rate will be 3.25%, the ECB deposit rate will be 1.50%, the Bank of England’s rate will be 3.25%, the Bank of Japan’s rate will be around 1.0%, the PBoC’s 7-day rate will be around 1.20%, and the RBI’s rate will be around 5.0%.

The financial side is the messy part.

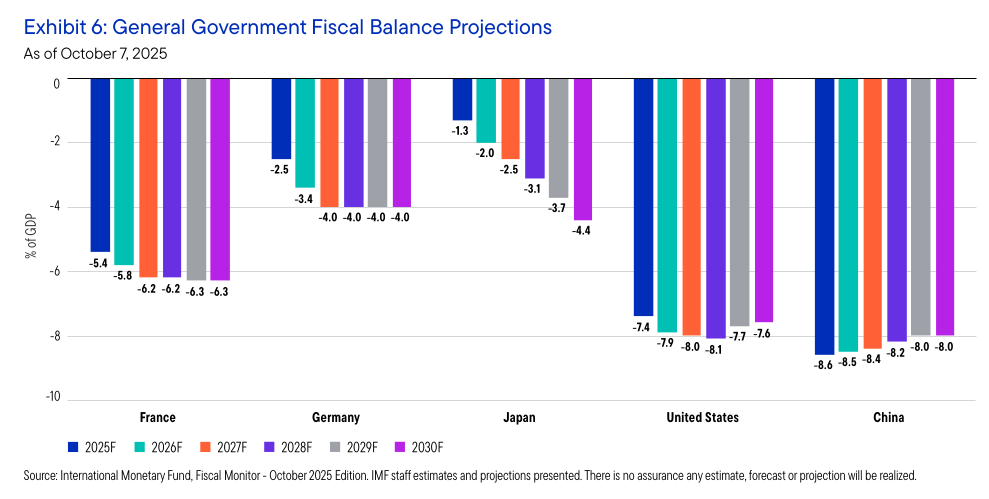

Franklin Templeton’s 2026 outlook says that we are now living in “an era of big and intrusive government.” This is most clear in the growing budget deficits of major economies. According to IMF data, economies like the United States will have a fiscal deficit of –7.9% of GDP in 2026, China will have a deficit of –8.5%, Germany will have a deficit of –3.4%, and Japan will have a deficit of –2.0%.

Franklin says that these imbalances are structural, not cyclical. There are the same basic forces at work in all of the major economies: growth is slowing, populations are getting older, social service needs are growing, and defense spending is going up. All of these things are keeping deficits wide even as economies grow.

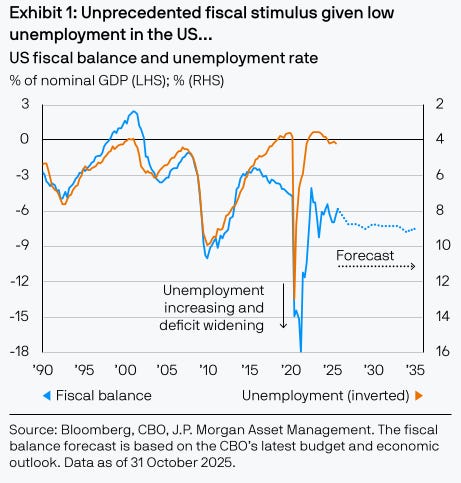

J.P. Morgan places the US situation in a sharp historical context. They note that “never before have we seen fiscal deficits… delivered outside of recessions.” In plain terms, the US is running recession-sized deficits even though the economy isn’t in a recession. This mix of monetary and fiscal fuel is helping sustain growth, but it’s also creating an unusual setup where deficits keep widening while unemployment stays low.

Amundi states that the “One Big Beautiful Bill” (OBBB) will add $3.4 trillion to US deficits over the next ten years. Many of its tax breaks and credits will help families make ends meet in 2026, which is a stimulus that will come even though unemployment is low.

Taken together with J.P. Morgan’s point, this creates a rare combination: the US is running a fiscally expansionary policy without being in a recession, something that has almost no historical precedent.

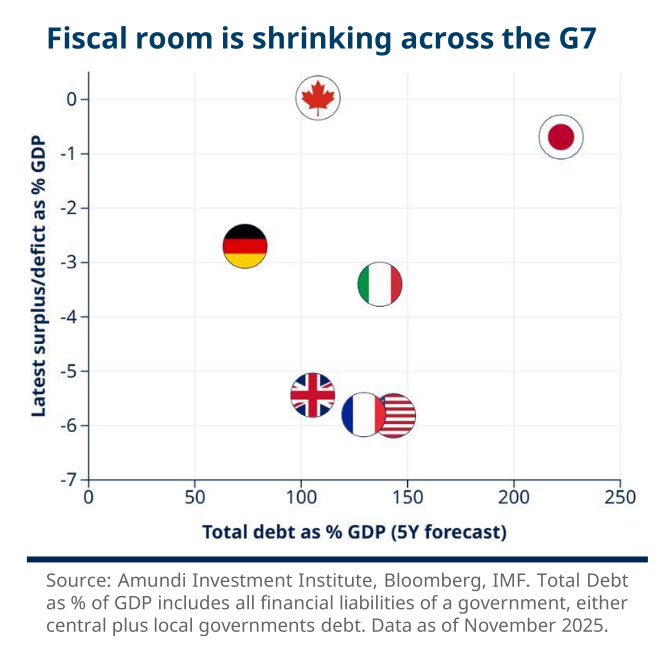

Amundi then looks at the G7 as a whole and comes to the conclusion that “fiscal room is shrinking across the G7.” Their study shows that there is a clear divide.

Germany has better public finances than most other countries, so it is using its limited fiscal space to spend more on defense and infrastructure because of slow growth and new security needs.

France and the US have the opposite problem: they have a lot of debt and deficits, but there is no political agreement on how to fix them.

Japan is the outlier. Even as the Bank of Japan begins gently raising rates, the government is shifting toward a more supportive fiscal stance under new political leadership. In other words, Japan is leaning into fiscal expansion at the same time its monetary policy is slowly tightening, which is the opposite of most other G7 economies.

But one theme that keeps coming up across most of these reports is fiscal dominance, the idea that central banks are increasingly constrained by governments’ heavy borrowing. Taken together, they point to the same concern. Major economies are running large, persistent fiscal deficits that are politically difficult to correct, and these deficits are starting to shape inflation, interest rates, and central-bank decisions in the US, Europe, China, and Japan.

AI, data centres, and the electricity supercycle

Now let’s turn to a theme that dominated the conversation in 2025 and is set to stay at the center of everything in 2026, you guessed it right, it’s AI.

What’s different this year is the way everyone is talking about it. It’s no longer just a technology story. In all the major outlooks, AI shows up in discussions about electricity supply, metal shortages, infrastructure spending, government budgets, jobs, and even geopolitics. It has moved from being a “sector” to something that shapes the entire economy.

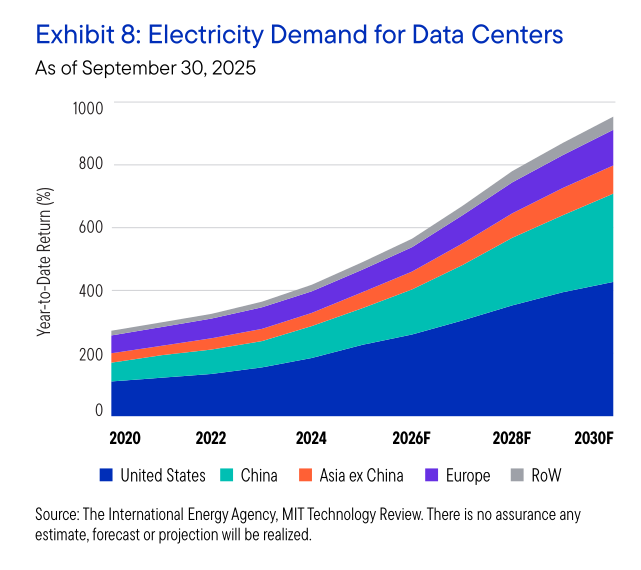

Franklin Templeton’s long-term outlook includes a chart showing data center electricity consumption rising steeply through the decade. Their point is simple: the first leg of the AI boom rewarded chipmakers and big platforms, but the next leg is going to hit a very real limit—electricity.

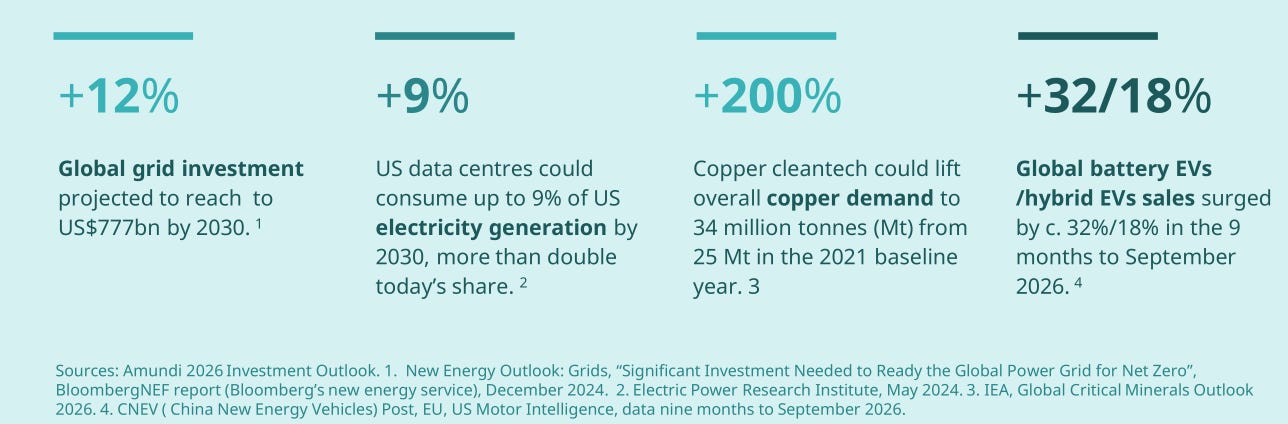

They describe AI as having a “vast energy appetite” and say that the world now needs to “feed the beast,” not by building smarter chips but by building a lot more power plants, strengthening transmission lines, and investing in large batteries and storage. And once you go down that path, you see the knock-on effects.

You need more engineering capacity, more copper, more rare earths, and more industrial metals—because behind every AI model is a physical world of cables, transformers, cooling systems, and substations that has to scale up too.

AI, they argue, now has a “vast energy appetite,” and meeting it will require enormous investment in generation capacity, modern transmission lines, and large-scale storage. This, in turn, spills over into engineering, basic materials, rare earths, and industrial metals, because every layer of AI infrastructure ultimately relies on physical systems, not just software.

Amundi looks at the problem from another angle, which is the grid itself. In many advanced economies, about 40% of the grid is over twenty years old and these networks were never designed for the combination we now have with rising data center loads, industrial electrification, and mass EV charging. Amundi points to research showing that updating these systems will take hundreds of billions of dollars over the next decade.

They also highlight how fast the demand is rising: US data centers alone could end up using close to 9% of the country’s electricity by 2030. Add the green-energy push on top of that, and the pressure on metals like copper jumps sharply, because copper sits inside almost every part of an electrified economy.

S&P’s Asia-Pacific Credit Outlook shows why this pressure becomes even more intense in Asia. The region already accounts for more than half of global emissions and almost two-thirds of new energy demand, according to the IEA—and that’s before adding the extra load from AI.

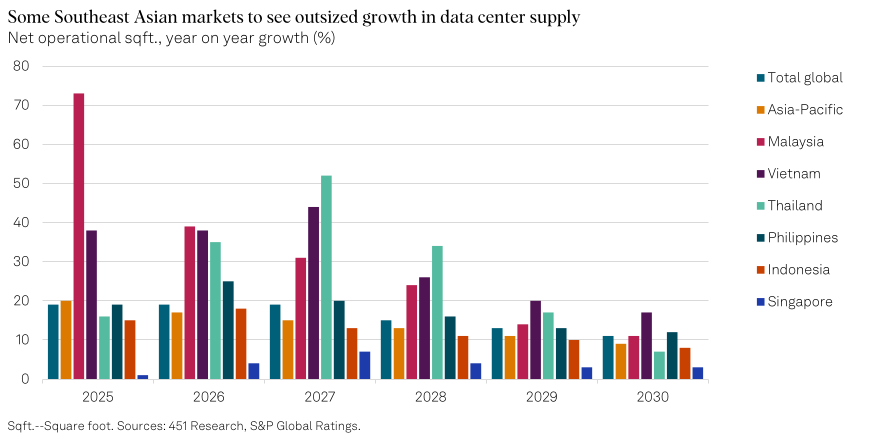

With digital adoption racing ahead, from payments and logistics to cloud computing and AI workloads, S&P warns that Asia’s energy demand “can only go up,” and that some countries could “see lost growth” if they don’t upgrade grids and improve resilience fast enough. They expect electricity use from data centers in the region to more than double by 2030.

However, the region faces practical constraints: markets in Southeast Asia are already seeing pressure on water supplies for cooling, and competition for power is intensifying—making it increasingly difficult to build and sustain large data center clusters.

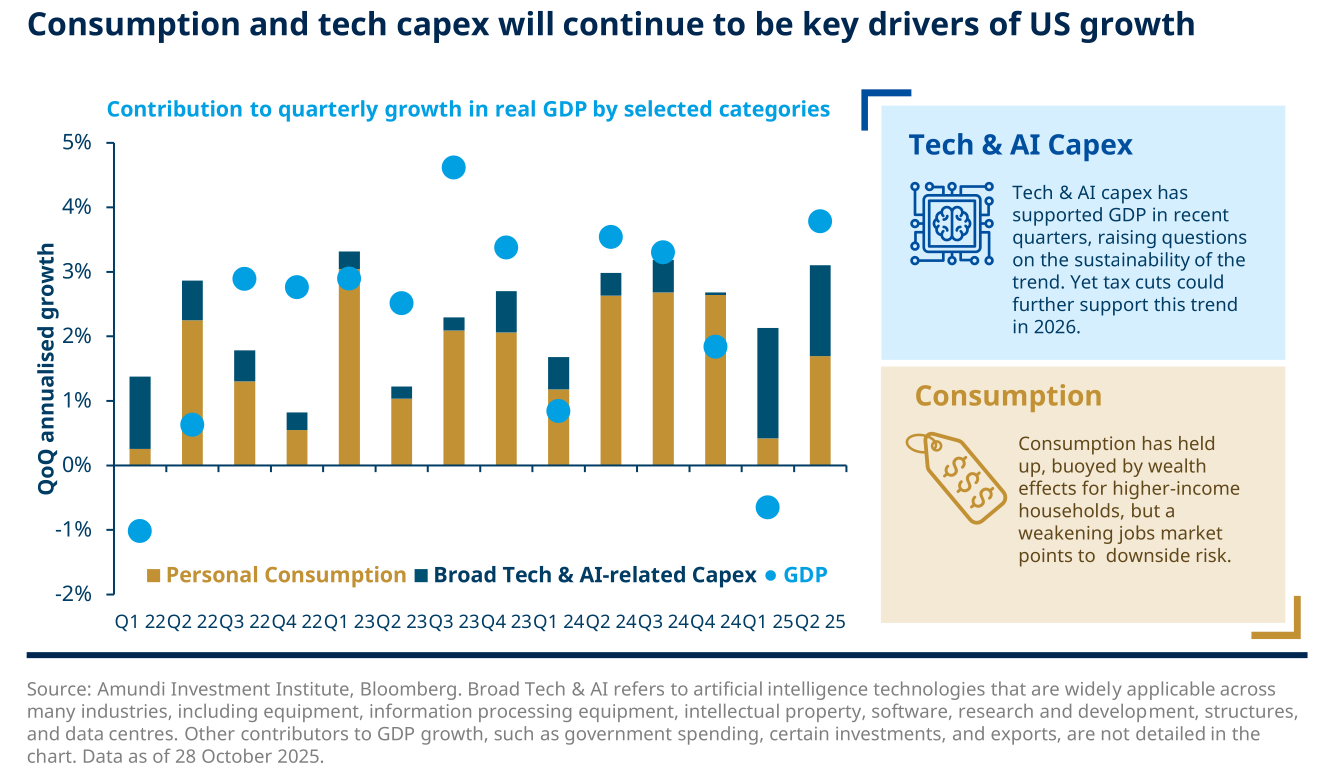

All this infrastructure spending isn’t just putting pressure on the system; the charts show that it has already become a major driver of economic activity. One of the clearest examples comes from Amundi’s 2026 Outlook. Technology and AI-linked investment are adding more to US growth than household consumption. Investment has stayed strong even as consumption has cooled, and that widening gap is a big part of why the US economy hasn’t lost momentum.

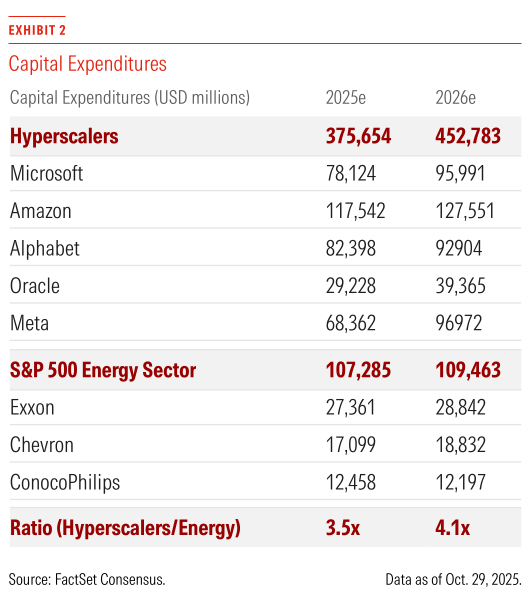

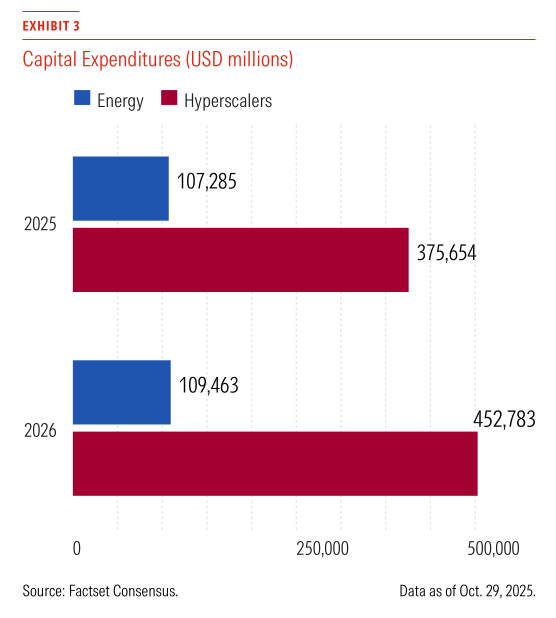

You see the same pattern in other reports, too. Morningstar’s global outlook highlights just how large the AI build-out has become. Most of the capital spending by hyperscalers—the big cloud and AI players like Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Meta—is climbing sharply from 2025 to 2026. The scale is striking: by their estimates, hyperscaler capex will be more than four times what the entire US energy sector is expected to spend. Goldman Sachs doesn’t give a precise GDP contribution, but this is exactly the kind of spending they have in mind when they describe data center construction as a central pillar of the US investment cycle heading into 2026.

While S&P shows that data center development across Southeast Asia, parts of Australia, and India has become a meaningful part of investment plans, backed by both private companies and utilities. They also explain that these projects require heavy upfront spending and increasingly complex financing. Instead of relying only on equity and bank loans, firms are turning to a mix of project finance, asset-backed structures, and, eventually, corporate bonds.

AI and inflation

A number of reports also draw a link between this global build-out and inflation, making the case that rebuilding energy systems, strengthening grids, and scaling up renewable capacity will keep investment needs—and therefore prices are now higher than they were in the 2010s. None of them say AI is the sole driver. But they all place AI inside a bigger structural investment wave that includes the green transition, supply-chain security, and national-security spending.

Put together, these forces make it difficult to imagine a return to the old low-inflation world. And because governments will have to support parts of this transformation—especially grid upgrades, storage, and resilience infrastructure—these investment demands also put pressure on public finances.

Franklin Templeton adds an important point about timing. The investment comes first; the productivity gains come later. Firms need time to understand how to use AI tools, train workers, and redesign workflows. The payoff only shows up after this adjustment, not at the start.

They also lay out what this means for workers. AI will phase out some roles and create others, but the transition won’t be smooth. There will be a period where companies experiment, workers adapt, and skill requirements shift. Productivity will improve in the long run, but getting there involves plenty of friction.

There’s also the geopolitical layer. J.P. Morgan notes that the US–China rivalry is increasingly shaped by access to advanced chips, compute capacity, and high-end AI hardware. AI capability is becoming a quiet marker of national strength. It influences industrial strategy, export restrictions, investment screening, and diplomatic relationships. Countries are now competing not just on software or model breakthroughs, but on who can secure the land, electricity, cooling water, and chips needed to run large-scale computing.

Impact on markets

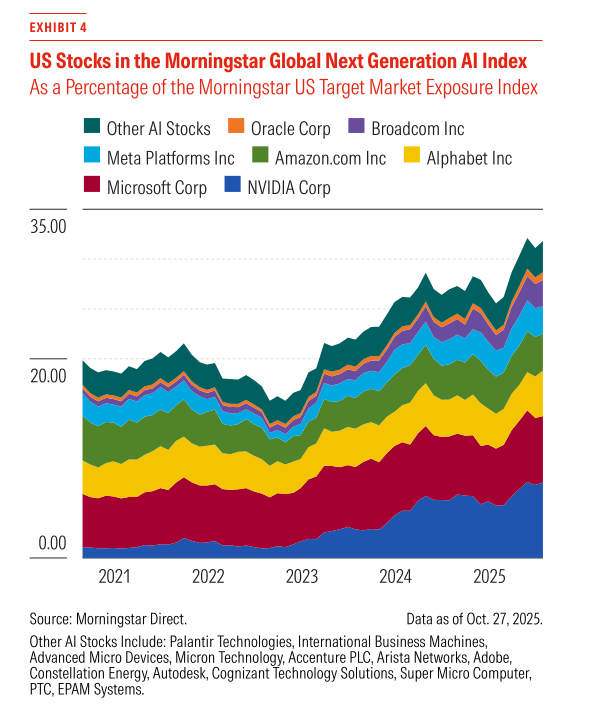

And AI is reshaping financial markets as well. Morningstar’s data on the Global Next Generation AI Index shows just how dominant US companies have become within the AI universe. A handful of mega-cap names have come to dominate the entire basket. NVIDIA, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Broadcom, and Oracle—together, they have pushed the US share of this AI index from under 20% a few years ago to well above 30% by 2025.

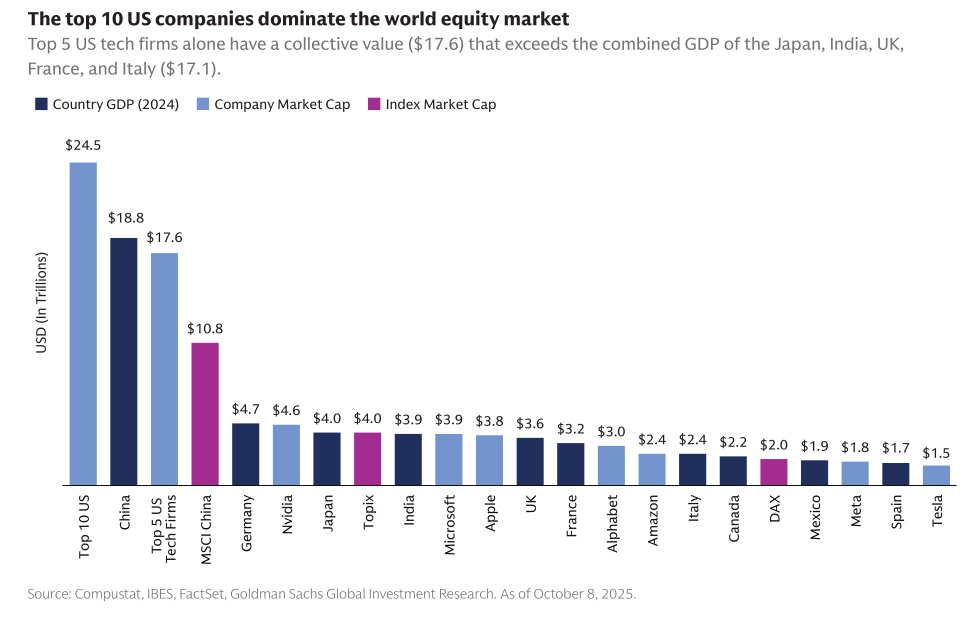

This is the concentration story that Goldman Sachs also talks about in their outlook: the enthusiasm around AI has lifted a small cluster of mega-cap technology firms to the point where they now dominate index returns. The chart makes the point visually—when so much of the market’s AI exposure sits inside a few companies, the entire index becomes more sensitive. If these firms move, everything else tends to move with them.

Across all these outlooks, one conclusion keeps coming back. The next chapter of AI won’t be defined only by model breakthroughs or faster processors. It will depend on the companies and sectors that build and maintain the physical foundation for all of this, which are the equipment makers, engineering firms, grid operators, renewable-energy developers, metals producers, utilities, logistics networks, and the data-center specialists who house and cool the hardware. AI is becoming as much a story about transformers, cooling systems, and copper as it is about algorithms.

That’s it for this edition. Thank you for reading. Do let us know your feedback in the comments.

Can i please get some clarity on Exhibit 8? Why does it say return on the y axis. I checked the Franklin Templeton report as well. No head or tail to it