Milky Mist is going Public - Here’s what you should know

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Milky Mist files for a ₹2000 crore IPO

SEBI brings order to the chaos of mutual funds

Milky Mist files for a ₹2000 crore IPO

If, like us at The Daily Brief, you live in South India, you probably have something from Milky Mist in your fridge. They're planning to go public with a ₹2000 crore IPO.

This gives us a chance to understand Milky Mist and how dairy companies work. But first, let's understand the basics of the dairy business.

How the industry works

Here’s what you should know about how your milk is procured. The journey has many moving parts that take a lot of time and money to sustain.

In India, every litre begins its journey on a farm that may milk anywhere between two cows or several thousand buffaloes. Roughly 65% of that milk still flows through the “informal” channel of local collectors and sweet-shops; the rest is funnelled into organised co-operatives like Amul and private dairies that can certify quality, pay by the milk’s fat-content, and bill the farmer by the end of the day.

Both the local milkman and big companies like Amul want to buy milk from the same farmers, creating a bidding war. The price farmers get for their milk keeps changing based on three things.

First, prices of cow fodder like hay and grain. When cow food gets expensive, farmers need more money for their milk.

Second, monsoons, good rains mean more grass for cows to eat for far lesser costs.

Third, during festivals like Diwali, everyone wants milk sweets, so prices shoot up.

Here's where it gets tricky, though. While farmers' prices keep changing, the price you pay in shops stays almost the same. Why? Because price revisions are politically sensitive. Even a small hike in the price of milk angers millions of voters, and state governments cap these increases just in time for elections.

This creates a huge problem for dairy companies, which already run on razor-thin margins. Imagine you run a milk business. You have to pay farmers more when cow food is costly, but you can't charge customers more because the government won't allow it. Your profit gets crunched from both sides.

However, saving just ₹1 by using a cheaper truck or a closer cold storage is as valuable as selling extra milk worth ₹1. So that’s precisely where milk companies try to build an advantage.

Collection, chilling, and transport, the first economic moat.

Raw milk goes bad incredibly fast. If you leave it outside the fridge for just three hours, it turns sour and you have to throw it away. Milk companies need to keep it cold through the journey from the farm to your home.

To solve this, companies like Amul and others build an entire cold chain system. Think of it as a network of veins spreading out from the main factory. Each of those veins has nodes, cooling centers in villages where farmers can quickly chill their milk. They have special refrigerated trucks that work like moving fridges.

They also have testing labs to check the milk at every step. This whole system has to work perfectly. If a truck is late picking up milk from a village, that entire evening's collection spoils and becomes worthless.

In this whole chain, Milky Mist has also found an interesting way to reduce costs. It uses some of its refrigerated trucks to carry finished products on the return journey, instead of running them empty.

This smart planning makes a huge difference, causing them to spend less on transportation. This means they have extra money to pay farmers better prices for their milk. In 2025, they had one of the lowest transportation costs in the entire industry.

Processing converts perishability into shelf-life and margin.

When milk arrives at the factory, it is processed through machines that do three important things. First, they heat it to kill germs (pasteurization). Second, they spin it really fast to separate cream from milk (centrifuging). Third, they mix everything back in the same exact proportions (standardization).

Why do all this? So that every batch tastes exactly the same. Whether you buy paneer today or next month, the taste is consistent across time.

This processed milk gets batched for two different uses. One portion gets packed into the pouches of regular milk. But the other batch turned into other value-added products where simple milk is transformed into daily eatables like butter, yogurt, paneer, and even fancier products like whey protein powder and desserts.

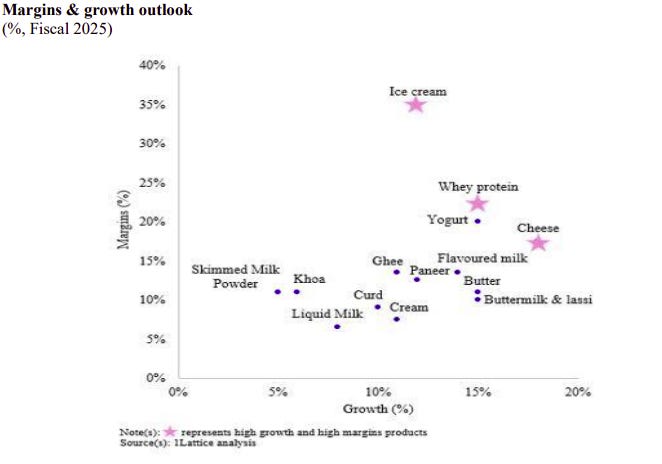

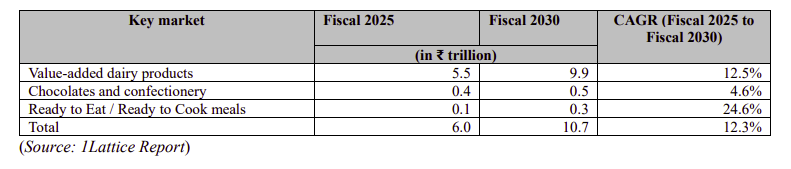

While cheese and paneer demand more machines and money upfront, they earn much more profit. A liter of milk yields ₹1 profit, but when that same liter of milk is converted to cheese, it yields a ₹3 gain. And value-added products are what Milky Mist deals in the most.

Milky Mist: laser focus on value-addition

Milky Mist started in Tamil Nadu almost 30 years ago. Instead of focusing on selling regular packeted milk like regular milk companies, they decided to make paneer, cheese, and curd their main money-makers.

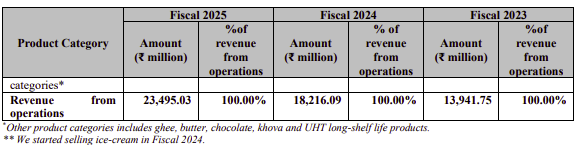

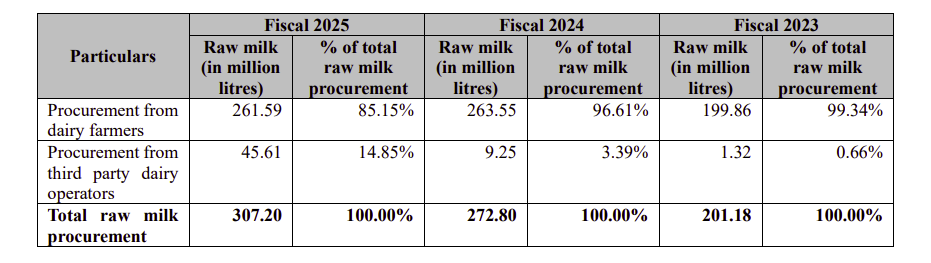

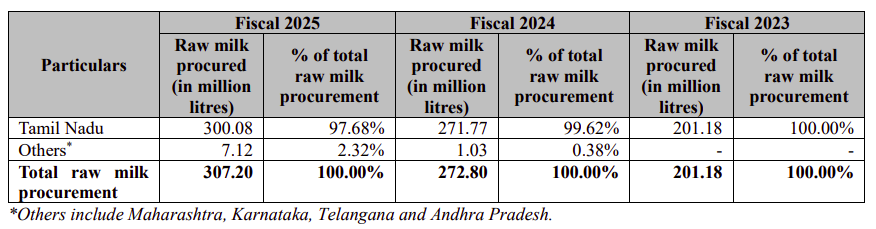

Today, Milky Mist buys more than 30 crore liters of milk every year. Most of it comes directly from farmers and some of it through third-party operators. The majority of their presence is in South India.

Since they buy directly from farmers, they know exactly what quality of milk they're getting, how creamy and fresh it is. This higher milk quality translates to better premiums on their value-added products as well.

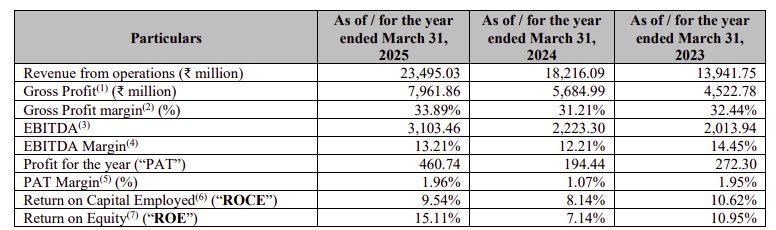

Milky Mist is growing incredibly fast. In 2023, they sold products worth ₹1,390 crores. By 2024, this jumped to ₹1,820 crores. And in 2025, it reached ₹2,350 crores. Their higher-value products are expected to grow really well in the coming years.

Interestingly, their final profit actually dropped from ₹27.2 crores in 2023 to ₹19.4 crores in 2024! But then in 2025, it shot up to ₹46.1 crores, more than 2x from 2024.

That drop in profits in FY24 isn’t without valid reason, though. Their cheese-making machines depreciated 30% in value. The loans to buy these machines increased finance costs by 25%. This ate into their extra sales for that year.

Manufacturing backbone and utilisation

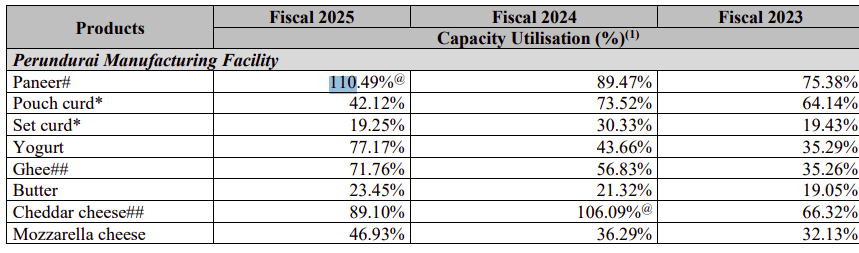

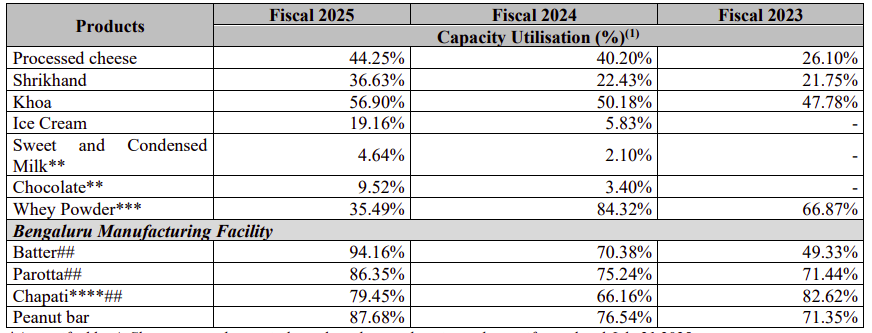

Impressively, Milky Mist just owns two factories. One is in Perundurai (Tamil Nadu) that makes paneer and cheese. Another is in Bengaluru that makes ready-to-eat foods like parottas and chapatis.

Each factory is designed to operate beyond its normal limits, maybe even using extra shifts. In 2025, their paneer-making machines — all of them in the huge Perundurai plant — ran at 110% capacity.

While this might reduce costs in the short term, it's actually worrying. Machines running this hard break down more often, and the quality can suffer. If something breaks, there's no backup.

Within products, the capacity varies, too. Yogurt and cheese production are at 70-90% capacity. The Bengaluru plant runs at 80-94% capacity. Ice-cream, however, is far lower at 20%.

But this low utilization isn’t necessarily bad for ice cream. You can't run ice cream machines full-speed all year because the demand depends on the season. They have room to grow when it’s summer or when they get more customers.

What the IPO funds will be used for

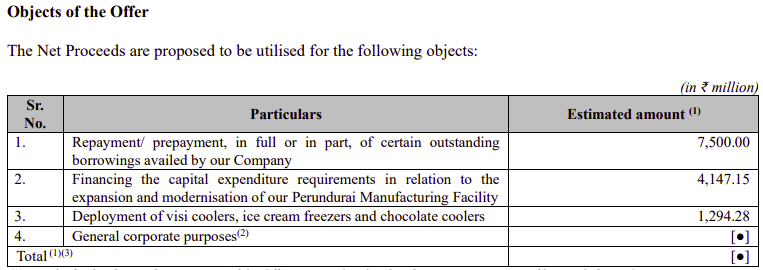

The money that Milky Mist raises (through a mix of fresh issue and offer-for-sale) will be used for four main things.

First, they'll pay off a big chunk of their loans. Second, they'll expand their production lines (both old and new) and upgrade equipment with modern technology, which we’ll cover in more detail. Third, they'll buy thousands of branded glass-door fridges that you see in kirana stores with the company's logo. Lastly, some money will be kept for day-to-day operational needs.

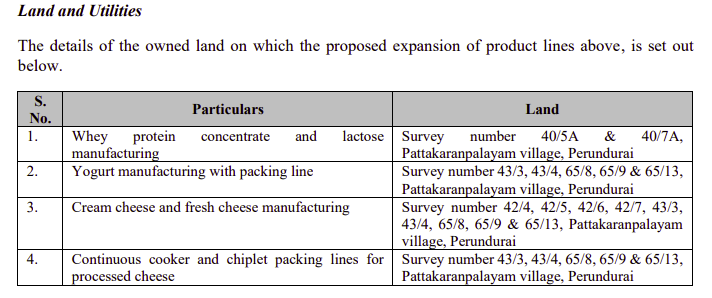

Within their expansion plans, they have three ambitious projects.

First, they’re expanding their whey protein and lactose lines. They have a really clever and scalable way of making whey. When you make paneer, you get solid chunks (the paneer) and leftover liquid (whey). Usually, the whey is thrown away or sold as cheap animal feed. But Milky Mist will turn this "waste" into expensive products. They expect to make 10 tons of whey protein and 44 tons of lactose daily.

Second, they're installing a super-fast yogurt production line that can fill 21,600 cups every hour. That's a dizzying rate of 6 cups every second!

Third, they're adding equipment to make more processed cheese - the kind used in burgers and pizzas. They'll also start lines of premium cheeses where profits are higher, like feta and gouda.

The expansion plan has another smart, cost-efficient aspect to it. Instead of building a whole new factory, they're adding these machines to their existing Perundurai plant. There’s no need for them to buy more cooling systems, waste treatment plants or steam boilers.

But, there are risks

The first risk is that of extremely high dependence for their milk procurement from just one state, nearly 98% came from Tamil Nadu alone.

This is incredibly risky. Imagine if your entire business depended on supplies from just one area. What happens if that area floods? Or if truck drivers go on strike? Your business stops overnight. That's the danger Milky Mist faces.

More worryingly, Milky Mist can’t readily hedge for this risk by procuring milk from other states as they haven’t built relationships with farmers there. They are trying to fix this. Last year, they bought 7 million litres from neighboring states like Karnataka and Maharashtra.

The second risk is quality control. In 2023, Milky Mist bought 99% of their milk directly from farmers. But things have shifted since. By 2025, 15% of their milk came from middlemen - companies that collect milk from many farmers and then sell it to others.

This shift is because they can’t find enough farmers to supply the milk needed for their growing business, but it also creates a problem. When buying directly, you can check if farmers’ cows are healthy, if they're using clean buckets, and if they're diluting the milk. But you lose this control with middlemen, who might mix milk from different sources.

To prevent this, Milky Mist now needs to test every batch from middlemen extra carefully. More tests mean more time and money spent on testing equipment and staff. The very thing that helps them grow also makes their business riskier and more expensive.

The third risk is production. Most of Milky Mist’s comes from the Perundurai plant.

If the factory suffers any kind of major damage, a fire, a flood, or an earthquake, they have no backup. The pollution control board could also order them to stop production for violating environmental rules. If the factory stops for even one week, stores can’t stock Milky Mist’s products, while other companies try to eat into their market share.

Finally, there’s distribution. Milky Mist doesn't deliver products directly to shops. They depend on distributors who don’t just handle the final delivery, but also perform other useful jobs. They pay Milky Mist upfront and collect money from shops later. They provide and maintain the branded coolers in small shops. They also share data about the best-selling goods.

But, these distributors are not loyal to Milky Mist. If Amul or Heritage offers them better profit margins, they'll switch immediately, and Milky Mist loses all those advantages that distributors gave them. Rebuilding this network would be incredibly difficult for them.

SEBI brings order to the chaos of mutual funds

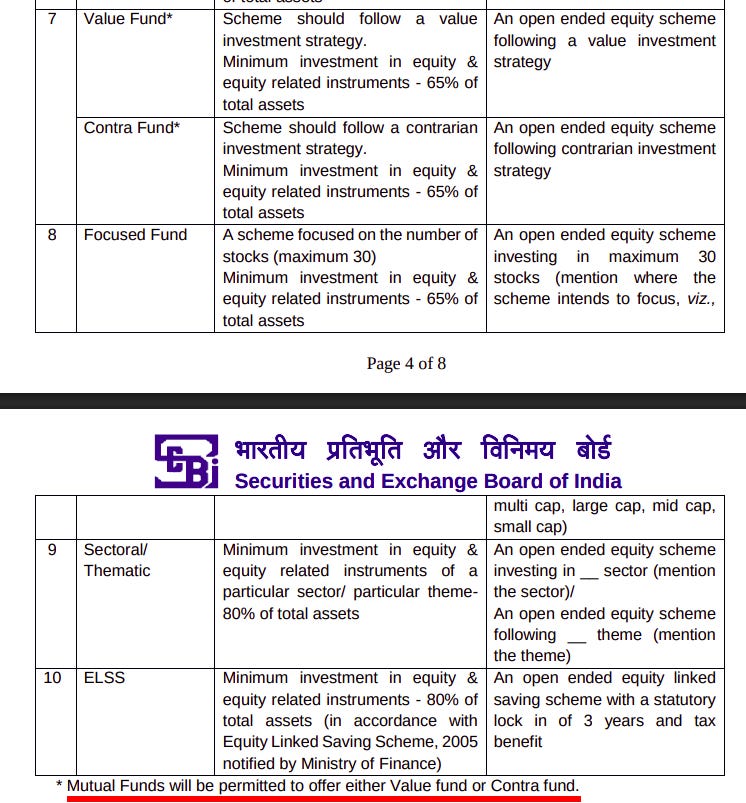

In 2017, India’s market regulator SEBI tried bringing order to the wild world of the then ₹20 lakh crore mutual fund industry.

Before that, fund houses would launch many schemes that effectively looked the same, leaving investors confused. But in October 2017, SEBI introduced a categorization and rationalization framework. No more would investors have to scratch their heads about how “XYZ Savings Plus Scheme” was different from “XYZ Income Saver Scheme”. A fund house, now, could just have one scheme per category. This brought standardisation across the industry, letting people make easy apples-to-apples comparisons between funds.

The landscape kept evolving. By 2020, SEBI saw the need to make more adjustments. While many of its changes were just minor tweaks to the 2017 framework, it also brought in entire categories, like “Flexi-Cap Funds”. All-in-all, SEBI was pursuing the same goal: keep fund categories meaningful and “true to label.”

Fast forward to 2025; we have a new set of proposals on the table. These aren’t final; SEBI’s still looking for public feedback right now. But it’s worth understanding what’s being discussed, since it’ll probably shape what you invest in, going forward.

Here are the biggest things we could find.

Duplication and distinction

Back in 2017, in the first round of SEBI’s industry-wide clean-up, it was zealous about a “one fund per category” rule. At the time, there was a sharp disconnect between what a scheme was called and what it actually did. Investors, especially non-experts, could get confused about what they were buying, and similar-sounding schemes from different fund houses weren’t actually comparable.

SEBI’s fix, one scheme per fund house per category, essentially forced clarity across the industry.

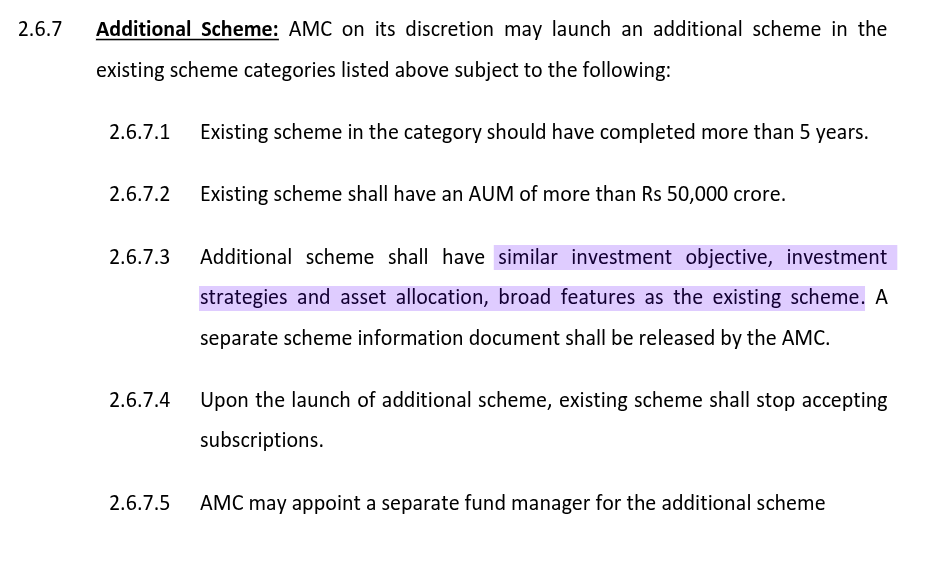

Now, however, SEBI’s willing to relax that rule. With more discipline in the industry, it’s willing to let fund houses break up massive funds, and offer two variants of the same idea. It might soon let AMCs launch a second scheme in the same category.

This isn’t an unlimited license; it applies to a small sliver of schemes. A fund can only introduce a new scheme if its original is at least 5 years old, and has over ₹50,000 crore in AUM. Only 13 schemes actually qualify. SEBI is essentially just letting fund houses duplicate this elite group of schemes. It still doesn’t want the pre-2017 overlap and confusion to return.

Any new scheme must be very similar to the original: same category, investment strategy, objective, etc. And the relationship between the two schemes must be clear. They should carry similar names, with clear suffixes, like “XYZ Series I” and “XYZ Series II”. Nor can they confuse investors with the fees they charge; the new fund’s expense ratio (TER) cannot exceed what the old fund was charging at the time of launch.

A new scheme, in a sense, substitutes the old one. When the second scheme (Series II) launches, the original fund (Series I) has to stop accepting new investments.

The consultation paper’s wording is a bit vague here. If the new Series II scheme has to broadly mirror Series I, what exactly is it solving for?

If the AMC still has to invest in the same or very similar stocks, why not continue doing it in the existing scheme itself?

Even if we argue this move gives fund managers more “flexibility”, however broadly we define it, what precisely can the new scheme achieve that the original one couldn’t?

These are some pressing questions raised after reading SEBI’s consultation paper. For definitive answers, though, we’ll likely have to wait until the final circular is issued.

Clamping down on lookalike thematic funds

Meanwhile, there’s a new way in which SEBI’s cutting down duplication: by preventing sectoral/thematic funds from looking similar.

Sectoral funds focus on a single sector, like banking, or technology. Thematic funds let you stick to broader themes and ideas, like green mobility, or infrastructure, bunching stocks from a variety of sectors. Broadly, however, both make a similar promise: they let you invest in a part of the economy you’re particularly hopeful about.

Historically, SEBI has offered unlimited leeway here, letting a fund house run multiple sectoral/thematic funds. In practice, however, these could end up holding very similar stocks. For example: a “PSU equity fund” and a “Infrastructure fund” from the same AMC could both just end up buying large PSU bank stocks. Investors that buy the two may feel like they’ve invested in different ideas, even when they get identical exposure.

This is a trap many investors fall into.

The numbers are mind-boggling. In 2023, total inflows into thematic funds were Rs. 30,840 crores. In 2024, it was more than four times as much, Rs. 1,40,132 crores. That’s insane! In fact, in 2024, thematic funds had more inflows than large, mid, and smallcap funds all put together!

What this means is that under an illusion of choice, investors poured more and more money into different thematic funds, only to end up owning the same stocks.

That’s what SEBI’s trying to do away with. It proposes that any two thematic or sector funds from the same fund house should not overlap by more than 50%.

But there’s also a small sphere where it’s loosening things.

Value fund vs. contra fund: Both allowed now?

There was a peculiar restriction that SEBI had added in 2017: a fund house could offer either a “value fund” or a “contra fund”, but not both.

In theory, both value and contra funds aim to invest in stocks with attractive valuations; however, the fund manager defines. Their approaches are supposed to be different: value funds look at fundamentals and bet on ‘undervalued stocks', while contra funds try moving against prevailing market trends. In practice, though, both types of funds could end up investing in a very similar basket of stocks. That’s perhaps why SEBI folded both together, avoiding duplication and reducing confusion.

Now, however, SEBI is coming to see the merit in separating them. It’s planning to let fund houses have one of each, provided they truly differentiate between the two. That is, the two portfolios shouldn’t overlap more than 50%.

Right now, there are a total of three contra funds in the market — maybe because of these limits. Perhaps that number will soon climb up?

Using the “residual” portion

SEBI’s rules define how much of a fund’s money goes into its primary purpose. This varies by the type of fund. An equity fund, for example, must put at least 65% in equities. Some categories could require 80% in a certain type of equity. And so on.

The rest of a fund’s money, its “residual portion,” is not tied to its main mandate. Managers often keep it in cash or other assets, giving them liquidity and allowing diversification. Until now, SEBI didn’t really mention what a fund manager could do with this residual portion. It’s filling in that gap now. This cuts down the leeway fund managers have, but in exchange, gives them clarity.

One place that fund managers would welcome clarity, for instance, is REITs and InvITs. While SEBI had never explicitly prevented fund managers from using their residual portion for these, it wasn’t clear that they were fair game. After all, these were “quasi-equity” investments. Although they gave predictable income, they carried a lot of volatility and market risk.

What did SEBI think about investments in such assets? Nobody knew. These didn’t really exist back in 2017, when SEBI first came out with its framework. So these weren’t technically a problem, but there was always a risk that SEBI would eventually clamp down on such investments.

Now, however, SEBI might explicitly let fund managers put the residual portion of most types of schemes into such funds, but not all. Very short-term debt funds, for instance, will be prohibited from doing so.

Changes in debt fund categories

SEBI plans to give debt funds a makeover. If you’re ever baffled by the alphabet soup of debt fund names, liquid, low duration, ultra short, etc., SEBI’s trying to make things clearer:

Clearer naming: SEBI thinks descriptions like “Low Duration” or “Short Duration” may not be intuitive. Instead of vague “durations”, they plan to shift the industry to standardised “terms”. All schemes that invest in instruments that mature between 1 and 3 years, for instance, shall uniformly become “short term funds”.

New debt funds added: Currently, all debt funds are categorized by duration or credit profile. There’s no way of investing in the debt of a particular sector. But now, SEBI wants to permit sectoral debt schemes, much like the sectoral equity schemes you already see. Such a fund could focus on bonds from a particular sector. You could use these, for instance, to only take exposure to infrastructure company bonds, or to banking sector bonds.

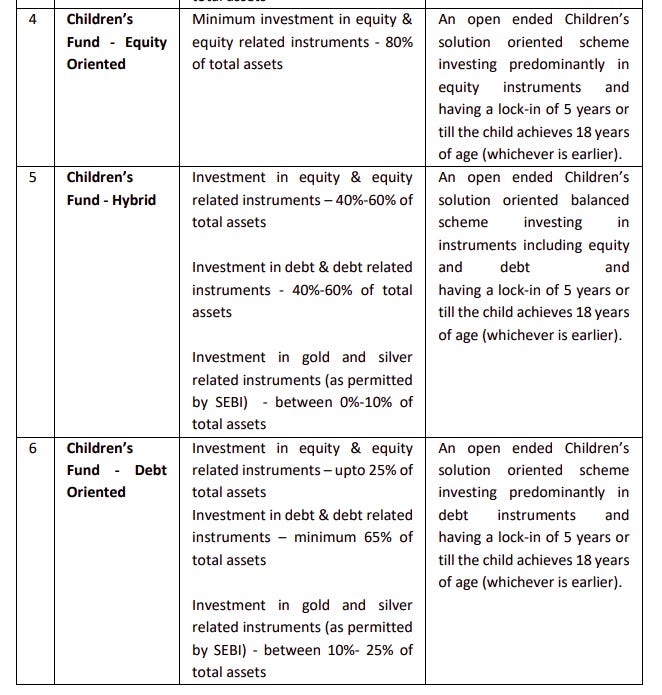

Solution-oriented and other schemes

There are schemes that are meant for specific goals, like retirement plans or children’s education funds. SEBI’s proposals could inject more flexibility here:

Multiple Variants for Goals: Typically, fund houses offer one retirement fund and one children’s fund. SEBI wants more diversity here; it wants mutual funds to offer different types of solution-oriented schemes, with varying mixes of equity and debt. For instance, if you’re investing for your children’s college education, your risk appetite may vary depending on how old your child is. So, SEBI’s creating categories like “Child Education Fund – Equity oriented” vs “Child Education – Hybrid”, letting you tailor the scheme to your risk appetite, without limiting goal-based funds to one template.

SEBI took investor choice to another level when it decided to introduce a completely new category.

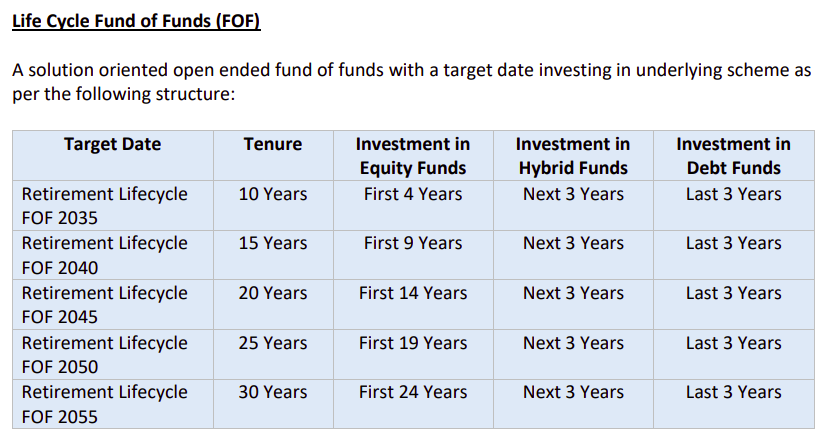

Life-cycle/Target date funds

Imagine you're investing with a specific year in mind. Maybe you're aiming to retire by 2040 or want to save for your child's college education in 2035—but you don't want the constant headache of managing your asset allocation year after year. Is there a product that fits this scenario?

SEBI now intends to allow "solution-oriented life-cycle fund-of-funds (FoF)," which will come with clearly defined target dates and lock-ins.

You'll select a fund based on your specific goal year. This fund will actually invest in other mutual fund schemes, automatically adjusting its investment mix as the target date approaches. Let us explain using an example:

Suppose in 2025, you invest in a Retirement Life-cycle FoF 2040, because you're targeting retirement in 15 years. During the fund’s early years, the manager would likely allocate more heavily towards equity, aiming for better returns. Since your retirement is still far away, even if equity markets face temporary setbacks, you'd have enough time to recover and remain on track toward your goal. Then, as the target date gets closer, the manager would gradually shift more of your investment into hybrid funds, and ultimately into debt funds, to protect you from unexpected market shocks as your retirement date approaches.

This framework is already common in the United States, and SEBI aims to introduce this innovation in India. It could simplify goal-based investing for many individuals. Instead of being overwhelmed by choices and lacking sufficient knowledge, investors could simply select a fund corresponding to their goal year, invest, and let the fund handle the rest.

For someone convinced about mutual funds as a wealth-building tool but burdened by decision-making, this innovation could significantly ease their lives—and might even completely transform the wealth advisory business.

From 2017 to 2025: An Ongoing Evolution

Mutual fund rules aren’t static; they evolve with the market. In 2017, SEBI began a one-time clean-up. Building from the base it created, it is now layering on incremental changes, perfecting things for the Indian market. That’s a good thing; it shows how the regulator is responding to the times.

Remember, as of now, these are just proposals, not final rules. These could still change. But whatever we finally get shall sharpen the edges of SEBI’s 2017 clean-up, preserving the clarity it brought, while giving the industry room to grow more meaningfully.

Tidbits

Remember Stargate? That’s now starting with a small data center in Ohio. Six months after that high-voltage White House launch, Stargate, the OpenAI–SoftBank joint venture, has completed zero deals. The two sides are stuck on basics like where to build. On paper, Stargate is still aiming for 10 GW capacity by 2029. But the reality so far? One pilot data center. Maybe. By year-end.

Source: Mint

We have a new results season for liquor brands! United Breweries posted a ₹184 crore net profit for the June quarter, up 5.9% YoY. But revenue fell 7.4%, dragged by a high base from last year’s election-impacted Q1. Still, volumes were up 11%, and premium beer is doing the heavy lifting. The segment grew 46%, led by Kingfisher Ultra, Amstel Grande, and Heineken Silver.

Source: Business Standard

A month ago, talks of an India-UK FTA were brewing. Now India and the UK are set to sign a landmark Free Trade Agreement on July 24, 2025, during Prime Minister Modi's visit to London. The deal promises significant tariff reductions, enhanced market access, and improved mobility for professionals, aiming to boost bilateral trade and economic ties.

Source: Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Kashish

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Fab stuff! Well organized explanations both!

I loved your explanation of Milky mist business model and how it works

Do it more often to make us understand different companies and industries thanks 👍