Lounge Access: Revoked?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Lounge Wars

Is Tata Motors losing its crown?

Lounge Wars

Airport lounges once felt like unaffordable luxuries. They’re still that for most of India. But if you’re one of the lucky few that regularly take flights, and own a credit card, you’ve probably found yourself stepping into these swanky spaces a lot more, in the last few years.

For that, you should thank a company called DreamFolks.

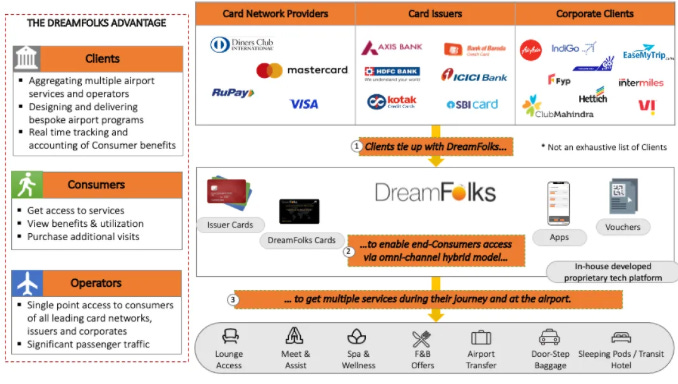

DreamFolks created the infrastructure that made airport lounges so commoditized and popular. It plays broker between banks and card companies who want to acquire more customers, and folks like you and me that dream of 5-star comfort before a flight. It’s an “aggregator” of airport lounges, playing the sort of match-making role that Zomato does for food deliveries.

Earlier this week, though, they indicated that they were being arm-twisted. CEO Liberatha Peter Kallat took to the news to criticize two major Indian airport operators (who she did not name). She accused them of using “pressure tactics” to unfairly malign DreamFolks. That immediately showed up in its stock price.

Her statement made us wonder: what’s happening? How can someone suddenly bully a company that occupies such a rarefied space? What role do they even play, and who stands to gain the most from them losing?

Behind this seemingly simple industry — and DreamFolks’ bold statement — lie ugly, and rapidly-shifting power dynamics.

Of dreams and relationships

DreamFolks’ business has boomed in the last few years.

Post-CoVID, as more and more passengers hopped on flights, DreamFolks’ business took off with them. Its revenue increased by 5 times in just 3 years — from ₹283 crores in FY22 to a whopping ₹1,292 crores in FY25. They’re profitable too, although their margins are razor-thin, with an EBITDA of around 8-10%.

In theory, it should be easy for anyone to enter this business. Theirs is an asset-light business, built largely around a technology stack. And there are other players they compete with, including PriorityPass — the largest such operator in the world. Yet, they utterly dominate the space, with more than 90% of every transaction for lounge access in India passing through their platform.

How? They have one huge moat — their relationships. Behind DreamFolks’ business are two types of relationships.

The first is with banks and card companies. These companies’ growth depends on having more customers, and one way to lure customers is to make them feel good. That’s why they offer a sense of luxury, through complimentary lounge access — sometimes even on simple debit cards.

But banks don’t really operate those lounges. So, how do they grant access for free?

This is where DreamFolks steps in. It signs multi-year agreements with these banks, giving their customers access to lounges in practically every airport in India. They track and account for these benefits through their technology stack. All they ask in return is a small fee each time a bank customer swipes their card for lounge access.

The second relationship is with operators of airport lounges and restaurants. Airport lounges don’t have direct tie-ups with banks. They don’t have a direct incentive to do so, either. Lounges are costly to run, after all, and it hardly makes sense for an operator to hunt for people to give free access to them.

DreamFolks fills in that gap. It takes in revenue from banks, and pays lounge operators or service providers to let people access them. The lounge operator makes more money on the side, while the bank makes its customers happy.

This is a win-win game. And at the centre of it is DreamFolks.

This image from the Invest Karo India newsletter summarises how these relationships work.

Not everything is rosy

There are some problems at the heart of DreamFolks’ business, though:

The thin margins are a feature. They’re fundamentally middlemen between big, institutional players that command serious power. It’s difficult to extract too much value from either side. The difference between what they charge banks and what they pay lounges has rarely exceeded 15%

If they tried to increase margins, they could be met with competition from one of the players building their own tech stack. DreamFolks has primarily benefited from being first to the game, but a tech-savvy player could build their own infra if the commercials start making sense.

DreamFolks doesn’t enjoy economies of scale. More customers do not bring better unit economics. Their costs grow the same way their revenue does, ensuring a linear rate of growth.

DreamFolks understands these bugs, so they’ve been diversifying how they make money — especially by expanding in non-lounge services like food, spa and wellness, baggage transfer and even doorstep visa delivery. They’ve expanded their services to Railways and highways as well, and have also established presence in airports outside India.

But none of this changes the structure of the game they’re playing — they’re just diversifying their revenue sources. Lounges continue to be their biggest money-turner.

And now, there’s a worse problem they’re facing. Some are annoyed by the privilege DreamFolks enjoys, that too on their own turf.

Enter airport operators

Airports require scale. There are just a handful of airports that are genuine money-spinners, and you need to win massive tenders to get your hands on them. It’s the kind of sector where monopolistic firms tend to dominate because of the sheer financial might they bring to the table.

In India, the largest such operator is Adani, which single-handedly controls a quarter of all airport footfalls in India. GMR is another major operator, owning the main airports of key destinations like Delhi, Hyderabad and Goa.

If you’re running an airport, you probably want to find as many ways of generating revenue as you can. One of them is to run lounges. While there are companies like Plaza Premium and Encalm who specialize in lounges, it makes sense for airport operators to get into the game. That’s what Adani and GMR are doing.

And lately, they’re also trying to build their own tech stack for lounges.

Why now? Well, it’s usually a crisis that presents an opportunity. Late last year, passengers across India were suddenly blocked from airport lounge access. DreamFolks’ tech stack had stopped working, and most airport lounges in India were dependent on them. Adani Airports, in particular, was mad. It alleged that DreamFolks was in “violation of its service agreements with the affected airports”.

Perhaps this episode gave them a new idea. Perhaps it gave them cover for an idea they had already conceived. We’re not sure.

Either way, airport operators saw an opportunity to fully bypass an aggregator like DreamFolks. In fact, just yesterday, Adani Airports CEO Arun Bansal publicly stated that “lounge access at airports no longer needs middlemen.”

But that wasn’t all — it soon dropped a bigger bomb by debuting its own digital platform to allow direct access to its own airport lounges.

Breaking up the party

Off late, it seems like all of DreamFolk’s carefully curated relationships are under threat.

Adani Airports could pull its lounges out of DreamFolks’ tri-party ecosystem. Now, that doesn’t kill off the business. Other lounge operators — estimated by DreamFolks at more than 60% of all lounges — continue to work with DreamFolks.

But banks are re-thinking their relationships, too. On July 1, DreamFolks announced that some travel-related programs with ICICI and Axis Bank had been canned, even though their multi-year agreement was still in operation. This came just weeks after a statement in May by DreamFolks’ chief business officer Sandeep Sonawane, who said, “Almost top 10 banks are now deeply integrated with us, and that's the kind of trust that they have shown."

Why are banks pulling out? This could be a response to last year’s service disruptions. It doesn’t help that offering lounge access (and other benefits) at low cost with little return has hurt banks’ pockets. To curb this excessive spend, many banks have recently limited benefits to those with more premium credit cards. In fact, even for premium cardholders, some banks are limiting benefits only to high credit card spenders. With fewer cardholders accessing lounges, the virtuous cycle that drives DreamFolks’ growth is coming under threat — especially since credit cardholders constitute an extremely miniscule part of India’s population.

But there’s a more serious claim by DreamFolks: that airport operators are flexing their power unduly on banks.

This is different from them merely entering the business and offering direct, fair competition. DreamFolks alleges that they have given banks an ultimatum — if banks didn’t bypass third-party firms like DreamFolks, the operators would ban their cards at their own lounges. It also claims that the authorities have been unwilling to regulate this matter due to their small size.

The stock market has responded to this flurry of events by expressing low confidence in DreamFolks, as it fell by 9% in just two days. More worryingly, over the past year, DreamFolks has fallen by over 50%.

Where does DreamFolks go from here?

DreamFolks will not give up without a fight. They’re saying to shareholders: “We have built this industry once – we’ll build it again.” They’re aiming to go beyond just making money through lounge access, and encompass all kinds of travel benefits. Much like PriorityPass, they’re also attempting to expand their own direct card program.

Even in the lounge business, they still have a solid value proposition, given how much trust they’ve built over time. They have also been working with corporate firms that issue cards to their employees.

But they face a steeper hill than ever before, with a behemoth like Adani Airports directly challenging them. A past error has also dented their credibility, with some of its big clients expressing doubts about their relationship. Perhaps that’s why the stock market has been so gloomy.

One thing is for certain: the airport lounge industry is hardly lounging.

Is Tata Motors losing its crown?

India's electric vehicles market is on a roll. In 2023, Indians bought more than twice the number of EV four wheelers as they did in 2022. In 2024, that number doubled again.

But even before it matures, this young market is already seeing the first of its great upsets.

See, there’s one name that was almost synonymous with the early foray of four-wheeler EVs into India: Tata Motors. They practically created the segment, and for a few short years, they dominated it. In 2023, the company controlled a staggering 73% of India's EV market. It sold over 6 times more EVs than the second biggest player in the market, and 30 times more than the fifth largest.

But the competition is starting to catch up, even as Tata’s advantages seem to be crumbling.

But how?

How Tata conquered the market

Tata came to India’s EV market well before the market really existed. It bought a series of advantages to bear on the space — from government permits to its own industrial ecosystem. In those early years, there was a lot that was going right for the company.

The early-bird advantage

Tata's path to EV dominance began in 2017.

This was back when most Indian automakers were still skeptical about electric vehicles. The government had just announced a huge tender — it was looking for someone to supply 10,000 electric vehicles to Energy Efficiency Services Ltd., a joint venture between various state-run power companies. Three companies applied for the tender: Nissan, Mahindra and Tata.

Tata won. By the end of the year, it had started rolling out its Tigor EVs to the entity.

This early entry provided Tata with a 3-4 year headstart over its competitors. It also had a guaranteed buyer for years’ worth of sales.

This gave them the opportunity to road-test their offerings, without the risk that their product would fail right out of the gate. It also gave them time to understand customer needs, refine technology, and build brand recognition. And it worked. Soon, Tata was India’s pioneering EV company.

Building a complete portfolio

From this early start, Tata set out to create a comprehensive electric vehicle lineup. It covered different segments with different price points and features with regular new releases:

Nexon EV (January 2020): Tata launched the Nexon EV in January 2020 — positioning it as India's first mass-market electric SUV. Priced around ₹14-16 lakh, it hit a sweet spot for the newly-curious middle class — it was affordable, yet feature-rich enough to feel premium. Soon, the Nexon EV was Tata's flagship product, with 50,000 units sold in 2023.

Tigor EV: The Tigor line of EVs, first released in 2017, was expanded substantially in 2021. This model specifically targeted commercial fleets and taxi operators — with its 315 km range and fleet-friendly pricing, it was practically built for businesses.

Tiago EV (September 2022): In September 2022, Tata launched the Tiago EV. Priced at around ₹8 lakh, it became India's first electric hatchback, and the most affordable EV in the market. This opened electric cars to budget-conscious city commuters, who wanted an eco-friendly daily car.

It would continue to expand this line up with EV variants of its Punch, Harrier and Curvv car models. This was a formidable line-up — Tata seemed to have offerings for every sort of customer.

Technology that worked for India

How did it get to this point so quickly? The company wasn’t trying to build new electric vehicle platforms from scratch. Instead, it started by converting its existing, successful petrol and diesel models into electric variants. This allowed it rapid market entry, while keeping costs low.

It married these old models to its new ‘Ziptron’ technology platform. This platform was developed in 2019 specifically for Indian conditions. Where international platforms were designed for different climates and road conditions, Ziptron was built with the intention to handle India's unique challenges.

The platform addressed key concerns Indian consumers had about electric vehicles. India was dusty for a lot of the year? Their batteries were dust-proof. India saw sudden downpours during the monsoon? The batteries were waterproof too. Temperatures ran too high in the summer? They had liquid cooling for extreme temperatures. Traffic kept stalling? The cars came with regenerative braking.

The biggest problem that customers had, though, was trust. They didn’t know if these cars could survive for long. And so, Tata offered an unprecedented 8-year battery warranty to build confidence in the new technology. It has now moved to a lifetime warranty on its batteries.

The Tata ecosystem

One of Tata's most significant advantages was that it was building its cars on top of an entire industrial base — the Tata Group ecosystem. Eight different Tata companies collaborated for an EV push that competitors couldn’t match.

Tata Power developed charging infrastructure, and provided home installation services. Tata Chemicals invested ₹800 crore in battery manufacturing and recycling facilities. Tata AutoComp Systems handled component manufacturing. Tata Croma promoted EVs through VR booths in retail stores. Even Tata Consultancy Services contributed with its technology and software development expertise to the project.

Many of the company’s vendors, in short, were its own group companies. This gave Tata incredible cost advantages and supply chain control. Where its competitors were mere car companies, Tata entered the fray with an entire ecosystem for electric mobility.

Policy alignment

On top of these advantages, though, Tata’s had government support.

In the early years, the Indian government had a two-pronged approach to electric vehicles. On one hand, the government gave generous sops to any Indian company that wanted to build EVs. On the other, it maintained heavy tariffs to keep the competition out. Tata benefited from both.

Tata Motors was the largest beneficiary of India's FAME (Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles) series of schemes. The scheme encouraged Indians to buy EVs, by subsidising their purchases. This brought Tata’s electric offerings nearly at par with petrol cars.

The company also benefited from the government’s Production-Linked Incentives (PLI). As the posterchild for “Make in India” EVs, the company received approvals for 15 out of the 27 applications it made under PLI schemes — securing ₹142.13 crore in incentives for FY24, and another ₹385 crore for FY25.

On the flip side, it was protected from outsiders. India has always tried to safeguard its automotive manufacturing industry, and it brought the same high import duties to EVs as well. We set import tariffs of 110% for premium EVs, making imported vehicles extremely expensive. This was a huge entry barrier for foreign EV giants, all of whom found it hard to displace Tata from its perch.

Tata starts losing its shine

But there’s a twist.

Despite all these advantages, we are seeing Tata's once-unshakeable dominance crumble. The company's market share has recently plummeted — from 73% in 2023 to just 35.4% by May 2025. In fact, its EV sales fell 13% year-on-year in FY25, in a market where its competitors are seeing triple-digit growth.

Despite having figured so much out, the company seems to have lost its lead. What happened?

Competition gets serious

For one, Tata’s competitors are finally learning to breach its moat. They’re attacking it wherever they can — price, range, charging speed, battery longevity, these have all become key battlegrounds.

From the very start, Mahindra was Tata’s biggest EV rival. But after playing second-fiddle for a long time, it has started outflanking the market leader.

In March 2025, it launched its "born electric" BE 6 and XEV 9e models. With ranges of 542-683 km, these new cars significantly exceeded Tata’s offerings. Customers proved enthusiastic, buying 10,000 units in just 70 days. On the very first day, in fact, Mahindra hit 30,000 bookings. Clearly, people were looking for alternatives to Tata's offerings.

Tata's primary challenger, though, almost came out of nowhere.

When General Motors, the company behind Chevrolet, decided to exit India in 2017, they sold their sole factory in the country to a rapidly-expanding Chinese auto manufacturer — SAIC Motor. In 2019, the company started operations from the plant, under the ‘MG’ brand, becoming the first Chinese auto manufacturer with a presence in India. It planned to invest ₹2000 crore into refurbishing the unit. But disaster struck immediately.

Midway through 2020, Indian and Chinese troops clashed in the Galwan valley. Suddenly, Chinese businesses were no longer welcome in the country. Many Chinese auto companies had to make a quick exit, as their Indian investments came under increasing scrutiny.

SAIC needed an exit too. This is when a consortium of Indian investors, led by the JSW group, picked up 51% in the company — leaving the SAIC with a minority stake.

MG came with more luxurious cars that had better range. But JSW MG Motor's real innovation was the Battery-as-a-Service (BaaS) model, which allowed customers to buy the car without owning the battery. This dramatically reduced upfront costs and eliminated concerns about battery replacement — addressing two major barriers to EV adoption that Tata hadn't solved.

The company is now extremely close to beating Tata for the top position. It achieved a 30.6% market share by May 2025, selling just 587 units less than Tata Motor.

There are others that are knocking at Tata’s doors. The Chinese giant, BYD, went from 1.95% market share in FY24 to 3.16% in FY25, making it the fourth largest player — despite facing 110% import duties.

The policy landscape shifted

Meanwhile, government policies are no longer as generous as they were to Tata.

For one, India’s becoming more pragmatic about its stance on foreign companies — instead of shutting them out altogether, we’re now inviting them to set up manufacturing in India. Recently, the Ministry of Heavy Industries passed a scheme through which imports from any country were opened up with a reduced 15% duty — as long as those companies invest $500 million in India. This could reduce prices of imported cars, while bringing global manufacturers to Tata’s door.

At the same time, Tata’s no longer receiving the subsidies it once did. The FAME-II scheme expired in March 2024, which instantly wiped away Tata's cost advantages. While the entire EV portfolio suffered, this was particularly brutal for Tata’s commercial offerings. Tata’s volumes were driven by taxi fleet operators. As the subsidies disappeared, their economic calculus shifted. As a result, Tata saw a catastrophic 92% drop in fleet orders — from 26,000 units in 2023 to just 2,000 units in 2024.

Fighting Back: Tata's Response

Don’t get us wrong. Tata might not dominate the segment any more, but for now, it still holds the poll position.

If anything, its profitability is improving. Despite losing market share, Tata Motors EV business achieved a positive EBITDA margin of 6.5% in Q4 FY25 — one of very few EV manufacturers globally to have a positive operating margin.

The company isn't giving up its market share without a fight either. It has announced an ambitious ₹33,000-35,000 crore investment plan, targeting 18-20% overall passenger vehicle market share by FY30. They have also invested ₹950 crore in a new battery gigafactory. It is planning range improvements across existing models and is introducing initiatives to narrow the price gap between EVs and combustive engine vehicles.

But perhaps the biggest news is its major structural change. Back in 2024, it decided to demerge its commercial and passenger vehicle businesses, turning them into separate listed entities. The could give its EV business the flexibility it needs to compete more effectively.

This story is far from over. But it's clear that Tata will no longer dominate the market as it once did. The next chapter will be written by multiple competing players. For consumers, this competition means better products, more choices, and faster innovation. And if Tata wants to hold on to its lead, it will have to work much harder for their business.

Tidbits

Just last week we wrote on Reliance’ soft drink shakeup with Campa Cola. We just learnt today that Reliance is embarking on a restructuring exercise that aims to group all its fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) brands, currently part of its retail ventures, into a new company so they get "specialised and focused attention", besides drawing investors focused on this segment. This will include Campa cola too.

Being a stock broker, we have covered major changes in this industry for our audience multiple times. This time it’s about Indian markets adopting single contract note for BSE and NSE. Previously, investors needed separate contract notes with details such as price, quantity and charges for each transaction when trading on the BSE and National Stock Exchange (NSE). This is done adopting a practice followed in developed markets such as the U.S.

RBI has been making a lot of changes to how lending companies operate their business. Be it how they are making it easy for SFBs by loosening priority sector lending rules, or changing its risk weights. This time they have come up with a new circular which is revisiting the prepayment charges rules. The RBI on Wednesday directed banks and other lenders not to levy any pre-payment charges on all floating-rate loans and advances, including for business purposes, availed by individuals and micro and small enterprises (MSEs). The directions will be applicable to all loans and advances sanctioned or renewed on or after January 1, 2026.

When we covered story on how Intel lost its edge, we got a lot of responses from our audience across platforms. Here’s an update to that story. Intel's new chief executive is exploring a big change to its contract manufacturing business to win major customers, in a potentially expensive shift from his predecessor's plans. The new strategy for Intel's foundry business would mean offering outside customers a newer generation of technology. This will be more competitive against Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co,in trying to land major customers such as Apple or Nvidia.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Prerana.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Amazing insights, as always. Keep crushing it guys! 💪