Just (can’t) do it?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Just (can’t) do it?

Indian pharma doesn’t face enough tests

Just (can’t) do it?

The energy from even the shortest Nike ad has the ability to energize you for the whole day.

For many people, Nike was never just a shoe company. In fact, growing up, Krishna from our team had a Nike poster on his wall. It represented a powerful, infectious idea — that greatness was within reach if you worked hard enough. Much like for him, “Just Do It“ felt like a definitive philosophy with which to live life.

But besides selling shoes, “Just Do It” embodied Nike itself.

In 1984, Nike wasn’t the biggest sneaker brand. But they saw something in a young NBA rookie named Michael Jordan that others missed. They pursued him with reckless desperation, offering him things no athlete — let alone rookie — had ever received. MJ got his own brand, royalties on every shoe, a true partnership. Adidas, Jordan’s preferred brand, wouldn’t match the offer. Nike bet the company on a vision nobody else believed in. They, well, did it.

But somewhere along the way, the feeling we got from seeing the iconic Swoosh logo somewhat faded. And when we started researching, we realised it wasn’t just us.

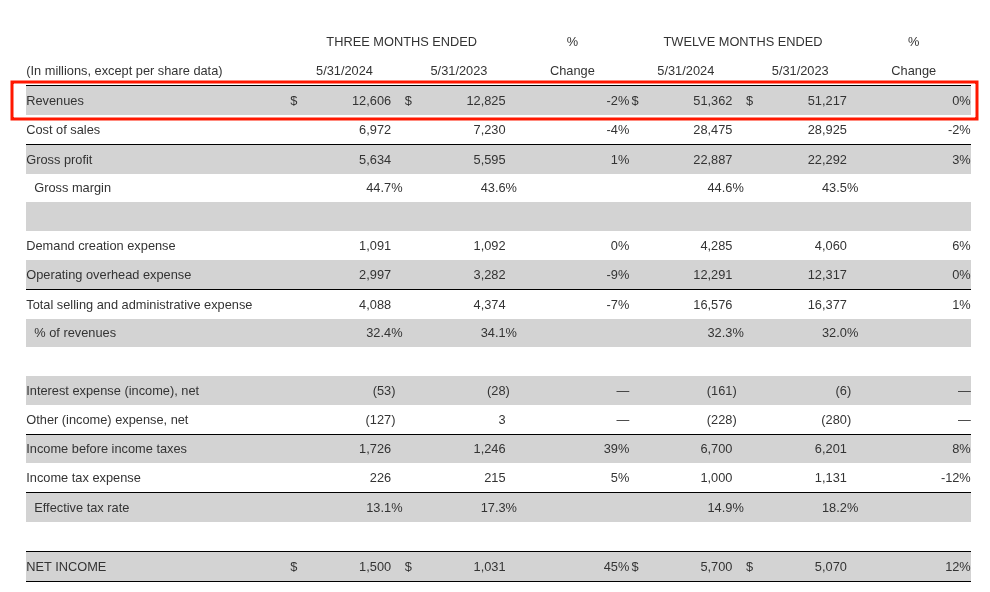

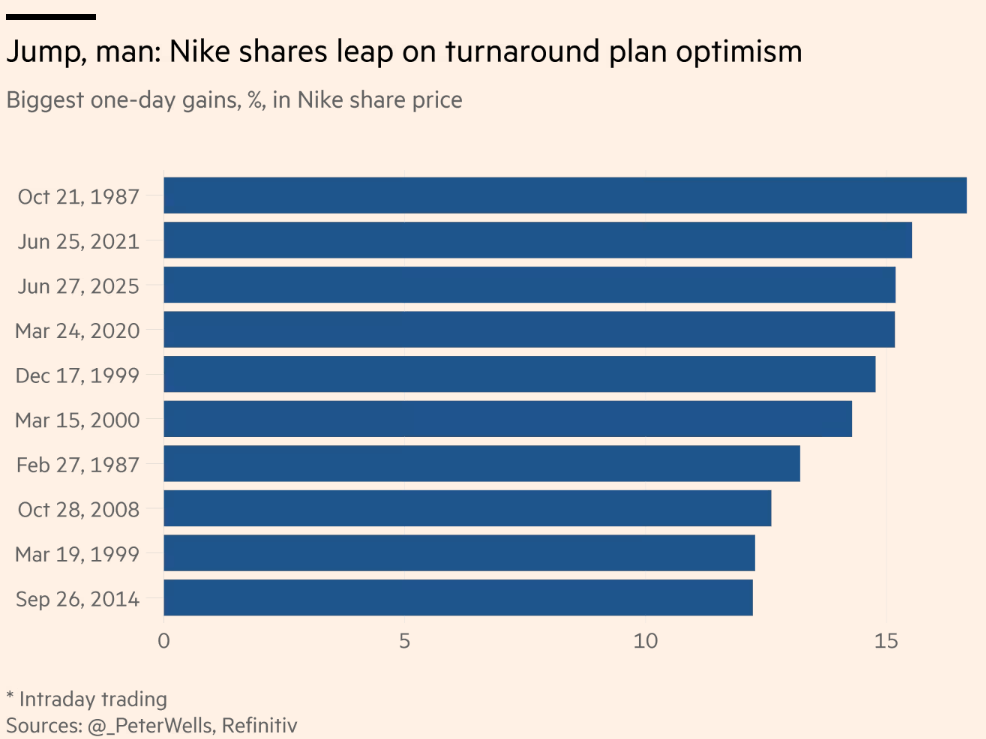

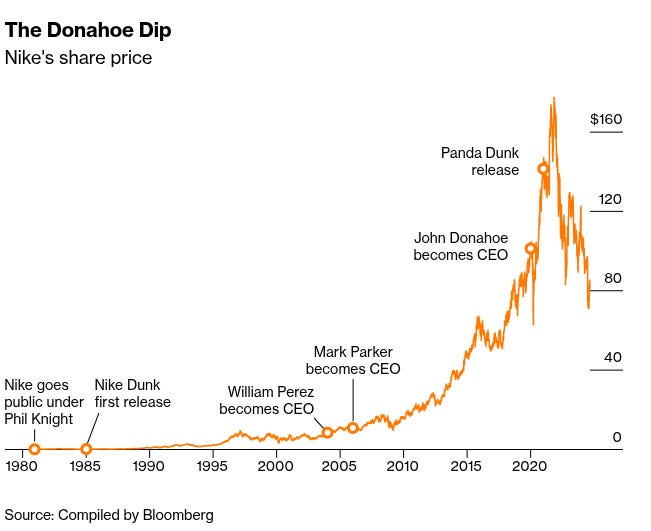

Nike’s stock has collapsed nearly 60% from its 2021 peak. In June 2024, shares fell 20% in a single day — the company’s worst since going public in 1980.

2024 was arguably Nike’s most difficult year in its six-decade history. Sales declined for three consecutive quarters across every geography. In July, the company laid off over 700 employees, including dozens of vice presidents and senior directors.

The company that taught the world to Just Do It was struggling to do much of anything. So, what went wrong?

Why do it?

The trouble began with a strategy that seemed smart at the time.

For decades, Nike sold most of its products through retail partners — like Foot Locker, Dick’s Sporting Goods, specialty running stores, and thousands of others worldwide. This model worked for sales, but it also meant sharing margins with retailers.

So, Nike’s leadership began asking themselves: what if we could sell directly to consumers instead? Their brand name alone would be powerful to sell shoes that way — why need a retailer? The margins would be significantly higher, and Nike would own the customer relationship plus the data that came with it. It would give them even more control of the brand.

So, Nike made some moves in that direction.

To start with, in January 2020, Nike hired John Donahoe as CEO. Donahoe was an outsider — only the second external CEO in Nike’s history. He came from the technology world, having previously run eBay and learned the mechanics of ruthless efficiency at consulting firm Bain & Company. He knew nothing about making shoes, but everything about online selling and efficiency. Nike’s board wanted his Silicon Valley expertise to build their online, direct-to-consumer pipeline.

Once Donahoe came in, he began with cutting ties with retailers Nike had cultivated over decades.

This was an extremely bold decision. After all, these were partnerships built over generations, so they went above and beyond merely being transactional. For instance, Foot Locker and Nike had worked together for fifty years — Nike products constituted ~75% of everything Foot Locker purchased.

But more than that, specialty running stores were special places where you felt like you discovered something new. They built their reputations on helping serious runners find the right Nike shoe. A customer would walk in, try on several pairs, ask questions, and receive expert advice. This is where a customer and a brand forged trust — something a website would find it hard to replicate. Yet, Nike cut the access of all retailers to the Swoosh.

At first, the strategy appeared to be working well. The pandemic had trapped everyone at home shopping online, so Nike’s direct sales surged by nearly $9 billion over three years. The stock soared to all-time highs in late 2021.

But Nike had made a fundamental miscalculation. They assumed that the pandemic changed consumer behaviour forever in favor of online — that nobody would buy shoes from a physical store anymore. And they couldn’t be more wrong.

When the world reopened, consumers still wanted to visit stores, try shoes on, discover new products in person. And when they walked into Foot Locker or Dick’s Sporting, the shelves that once held Nikes were now stocked with unfamiliar brands eager for the opportunity Nike had handed them.

At the same time, in an attempt to cash into nostalgia, Nike leaned heavily into its archive rather than investing in new innovation. After all, wouldn’t you want to wear the same shoes that Michael Jordan did? So, the company flooded the market with retro releases — Dunks, Air Force 1s, Jordans — in endless colourways. One such shoe, The Panda Dunk, initially resold for triple its retail price.

But Nike couldn’t resist overdoing it. They kept restocking until the exclusivity that once made sneakerheads queue for hours had completely evaporated. Combined with the direct-to-consumer misstep, the stock dip was so catastrophic that Bloomberg called it “the Donahoe dip”.

There Is No Finish Line

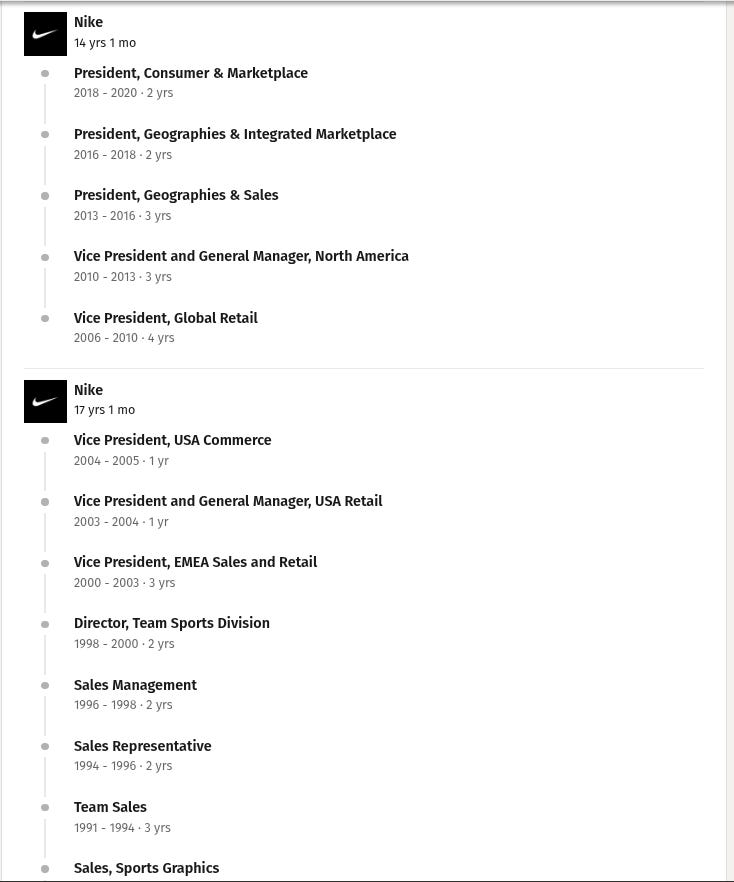

In September 2024, Nike saw John Donahoe out the door. They replaced him with Elliott Hill, a retired Nike veteran who spent a whopping 32 years at the company. Hill’s LinkedIn profile is iconic today — it reads like a history of Nike itself!

Hill joined Nike as an intern in 1988. What he thought was a short-term position turned out to be a six-month internship. He spent his early years driving a minivan across small towns in Texas and Oklahoma, hauling Nike clothing racks into the back entrances of sporting goods retailers. He even paid for his own product samples out of pocket. He genuinely believed in the Nike ethos.

That belief paid off. Hill worked his way up through sales, earned the trust of co-founder Phil Knight, and eventually ran the company’s entire consumer and marketplace operations. By 2020, he had become a strong contender for CEO.

But instead, he retired, exhausted after decades of relentless pressure. Knight reportedly refused to accept the decision, calling it a “quit” rather than retirement. Four years later, the board — particularly Knight himself — asked him to come back.

On his first earnings call as CEO, Hill declared: “We lost our obsession with sport.” He acknowledged that Nike had leaned too heavily on a handful of retro franchises, admitting:

“I don’t know if we’ll ever see again where we are today - three shoes being as big a piece of the pie as they are. I don’t think it’s healthy. We need a broader base. We need to be looking forward and trying to take consumers somewhere they’ve never been before.”

His immediate priorities were rebuilding relationships with the retailers Nike abandoned, reinvesting in performance innovation, and restoring the company’s connection to actual athletes. But he’s warned investors that the turnaround will take time, and results will worsen before they improve.

If You Let Me Play

When Nike vacated retail shelves, two brands were perfectly positioned to fill the space: On and Hoka.

For years, On grew through word of mouth rather than any marketing spend. The founders focused on convincing specialty running store owners that their CloudTec cushioning technology was genuinely superior. If the store owner believes in your product, they’ll recommend it to customers, and you build authentic credibility as a performance brand.

This strategy required distribution access that Nike inadvertently provided. When the Swoosh retreated from retail, On and Hoka suddenly had access to premium shelf space that retail stores were already looking to fill up.

On’s revenue reached approximately $2.5 billion in 2024, growing an impressive 30% year-on-year. They’re still a fraction of Nike’s scale, but they’ve hardly spent as much time in the market as Nike has. And On didn’t defeat Nike in direct competition. Nike stepped aside and opened the door. In fact, On’s co-CEO Martin Hoffman said as much that Nike’s stumble “is one reason why On and Hoka exist today.”

Impossible is nothing?

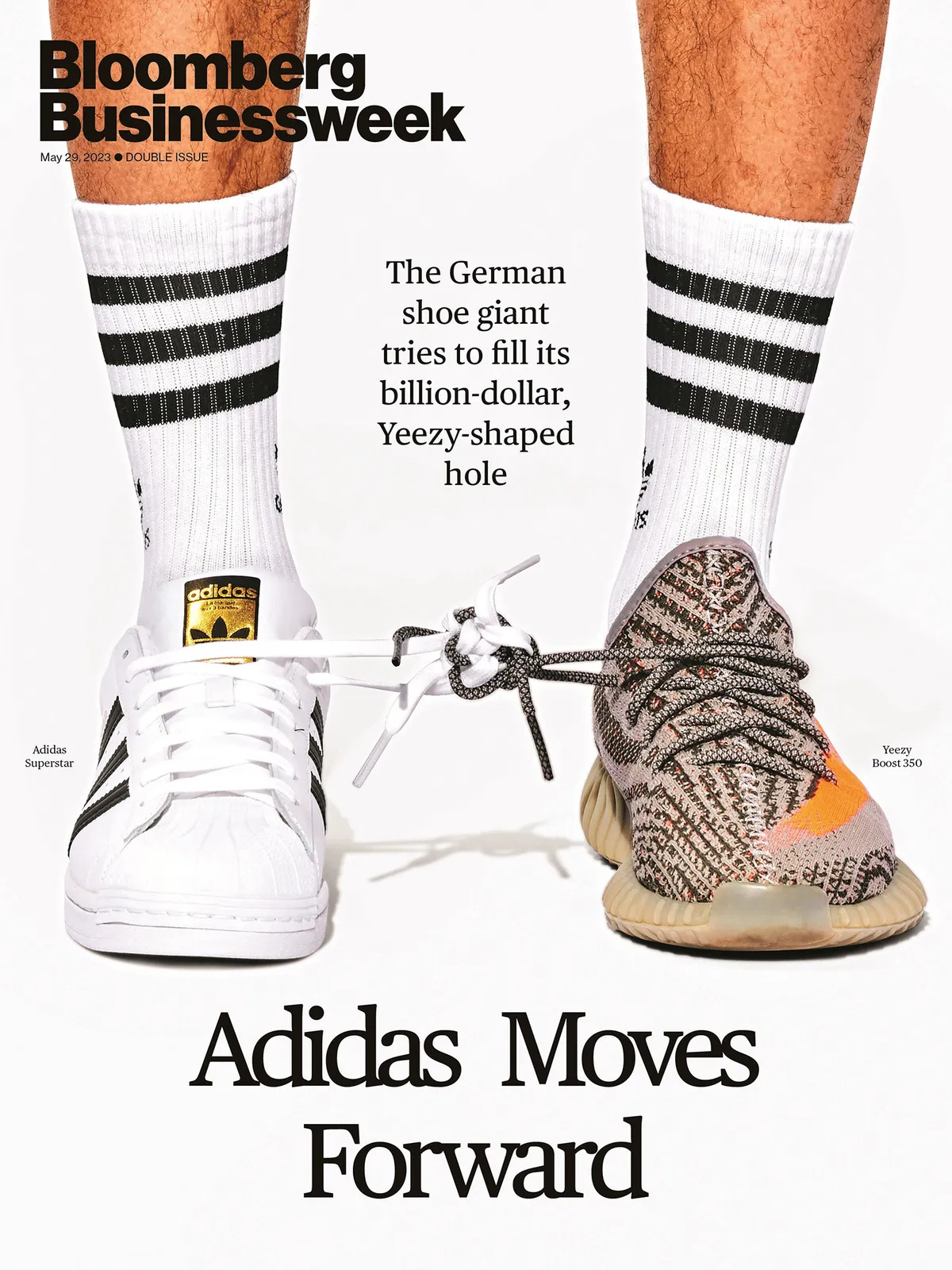

While Nike wrestled with self-inflicted wounds, its long-standing rival Adidas faced an entirely different catastrophe.

For much of the last decade, Adidas’ business was defined by its partnership with American rapper Kanye West. The Yeezys — named after an alias of Kanye West — generated a whopping 40% of Adidas’ profits despite only making up 8% of their revenue. Owing to their exclusivity and their association with the musician, the Yeezys commanded premiums like they were rare, antique items.

But this outperformance came at the cost of a dependency. In itself, a dependency isn’t always bad, but wherever Kanye walked (or tweeted), controversy came running right behind. Kanye made many antisemitic statements over time, forcing Adidas to terminate the partnership in late 2022. But as a result, they were left holding over $1.3 billion worth of unsold Yeezy inventory. With Yeezy profits disappearing overnight, Adidas projected an operating loss exceeding $700 million for 2023. This was their first loss since the early 1990s.

Now in the trenches, the board recruited Bjørn Gulden from their rival Puma — interestingly, Puma and Adidas were started by 2 brothers who hated each other. Gulden had spent a decade successfully revitalising the Puma brand. He had to replace the Yeezy megawhale somehow.

Gulden’s turnaround has centred on two pillars. First, he’s leaned into retro styles — particularly the Samba and the Gazelle — that have caught a genuine fashion moment. Unlike Nike’s retro fatigue, Adidas appears to have timed this wave correctly. Secondly, Gulden pushed Adidas to become competitive in running again, with the company’s running business expanding by more than 30% recently.

The turnaround remains incomplete, but there are signs the company has stabilised and begun climbing out of the Yeezy drama.

Write The Future

With this, the sneaker industry may be at an inflection point.

Analysts from The Bank of America argued that the 20-year sneaker boom has passed its peak. The structural shift that fuelled the industry’s growth — where people replaced dress shoes with sneakers in virtually every context — is largely complete. Sneakers now account for ~60% of all footwear sold in the United States. There’s not much more market share to capture. Future growth may be fairly low.

Maybe, the future belongs to specialist brands rather than generalists. On and Hoka, for instance, have proved that consumers will pay premium prices for brands delivering genuine performance innovation in specific categories. The era of a single company owning everything may be giving way to an era where different brands own different domains — simply due to the nature of how fashion cycles work today. Take On for running, someone else for basketball, someone else for football, and so on.

This inflection point represents three different bets. One, Elliott Hill is betting he can restore Nike’s primacy through renewed focus on sport and innovation. Two, Gulden is betting on retro momentum and running improvements. Three, On and Hoka are betting that performance credibility translates into mainstream scale.

But in any case, the old order dominated by Nike has cracked. The days when a single swoosh dominated every shelf and every sport may not ever return. The sneaker world is moving to a new era, where the companies that thrived in the previous era will need to become something new to survive the next one.

They’ll have to believe in something (new), even if it means sacrificing everything (old).

Indian pharma doesn’t face enough tests

When it comes to researching and developing pharmaceutical drugs, failures are normal to have — and may even be necessary for success. But once a drug hits the market, these failures cannot take place.

Alarmingly, this happens in India quite often. In October last year, over 20 children in Madhya Pradesh died after consuming a contaminated cough syrup. In 2022, the deaths of 66 children in The Gambia were linked to another Indian-origin cough syrup. A recent academic study found that a large chunk of Indian cancer drugs meant for exports failed quality tests.

This is an unacceptable outcome for an industry that’s dubbed “the world’s pharmacy”. Why does India’s testing infrastructure for drugs fall short of finding such issues on time? We’ve briefly touched upon this in past Daily Brief editions, but never covered it in and of itself until now.

We ended up finding a vast, complex world governing India’s medicine-testing — we won’t be able to cover all of it in one episode. But, we’ll look into the most important structural reasons for why India struggles to check the quality of our drugs.

A house, divided

To understand the core of India’s drug-testing framework, we must first dig deep into how the government approaches it.

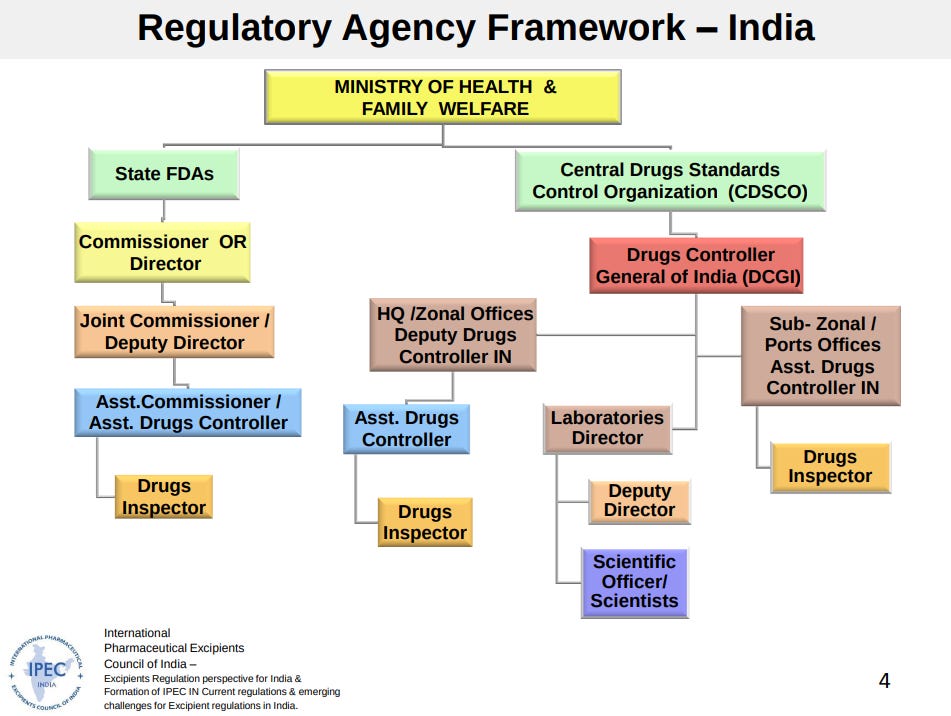

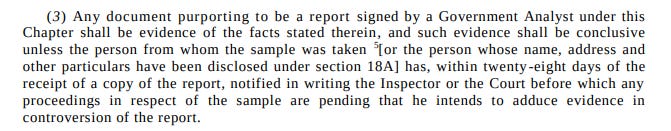

At the national level, there are two public bodies that govern drug-testing: the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) and the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission (IPC). In collaboration with the IPC, the CDSCO sets standards that every drug should meet. It also grants manufacturing licenses for all new drugs for a period of 4 years.

However, the day-to-day enforcement of Central standards is done by states. Each state has its own food & drug administration (FDA), which conducts factory inspections and tests drug samples within its borders. In fact, once the first 4 years of a new drug ends, the powers of issuing and revoking licenses lies entirely with states where the factories are located. The Centre cannot intervene anymore.

In theory, this decentralization should allow states to monitor their local manufacturers closely. Unfortunately, the practical reality couldn’t be more different.

For one, state FDAs are chronically understaffed and overwhelmed. In 2012, a parliamentary committee found that India needed around 3,200 drug inspectors. But only 846 — just a quarter — were actually in post. Even Maharashtra, home to a big pharma cluster, operated with a 77% shortfall in drug inspectors last year. A single inspector might be tasked with overseeing tens of factories, stretching them thin. As a result, smaller units could go years without proper inspection.

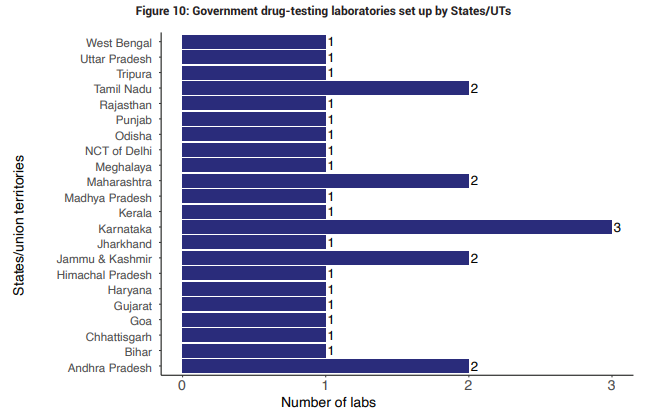

Nowhere is this capacity problem more evident than in the lack of drug-testing labs. Several Indian states don’t have a functioning drug-testing lab at all. States with minimal lab infrastructure conduct only a minuscule number of quality tests each year. As a result, substandard drugs often circulate undetected there.

Additionally, to conduct impurity tests, state labs need to buy impurity standards — which are pure samples of the known impurities in a drug. However, these standards, which are often bought from abroad, can be very expensive. The IPC itself also supplies them, often at much cheaper rates, but it doesn’t make enough of them.

Even states with powerful pharma clusters are painfully short of lab capacity. For instance, Telangana, which accounts for nearly 40% of India’s drug output, was almost entirely reliant on a single public lab in Hyderabad last year. So is Himachal Pradesh, which alone is a massive supplier of medicines to the world.

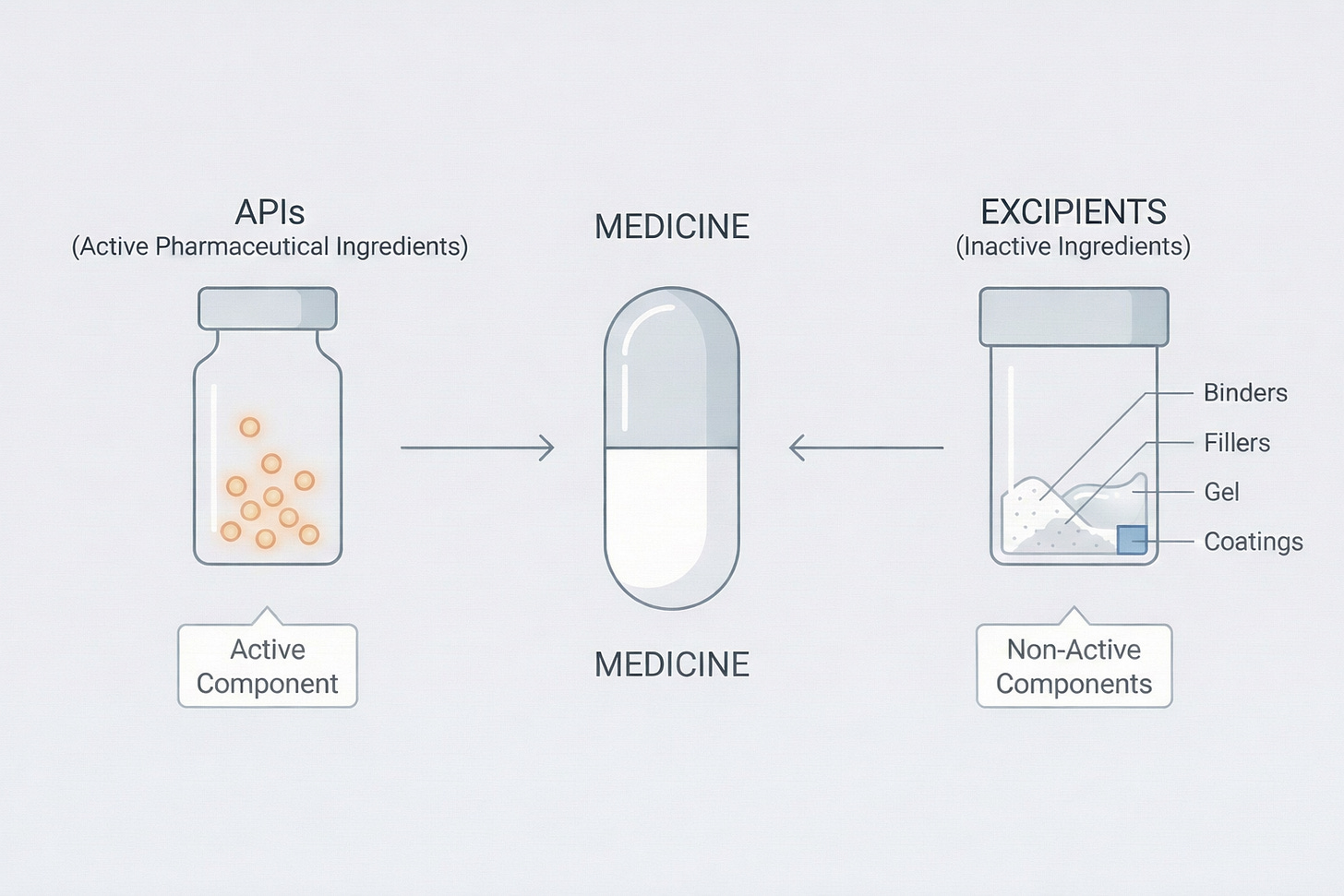

Now, you might be wondering: what about private labs? They do exist, and are also publicly-accredited by the NABL. But, as per the Drugs & Regulations Act, a test is only legitimate if it is conducted by a government analyst. Eventually, a private lab has to get a government stamp for every report, without which it has no legal standing. This leaves little incentive for private players, especially since labs also cost a lot to build.

What adds to the complications in India’s enforcement mechanisms is a concept called “loan licensing”. In this, Company A, which has a license to market a drug, uses Company B’s facility to produce those drugs. In effect, this is a form of contract manufacturing. It is often done by firms that don’t get a license in one state with a pharma cluster, but do so in another with much less presence of a pharma supply chain.

For a long time, India’s laws have barely addressed this. So, when something goes wrong, accountability fractures.

Say that company A sells in Telangana, but company B’s factory is located in Karnataka. Who’s responsible in that case? Karnataka must take action against the factory, but they may not even know there’s a problem until Telangana alerts them — if Telangana catches it at all. Neither state has the power to inspect the facilities in the other state. This makes it extremely hard to decide who’s accountable, and by how much.

What makes this worse is that states rarely impose penalties on their own manufacturers for not conducting impurity tests. For instance, manufacturers are legally required to provide state labs with placebos, which help in testing. However, they often don’t cooperate, in which case, state labs with not enough resources simply skip basic impurity tests. Meanwhile, dangerous medicines continue to circulate through the cracks between jurisdictions.

The excipient problem

The fragmented regulatory structure is only part of the story. How the drugs themselves are made reveals a gaping hole in India’s testing infrastructure.

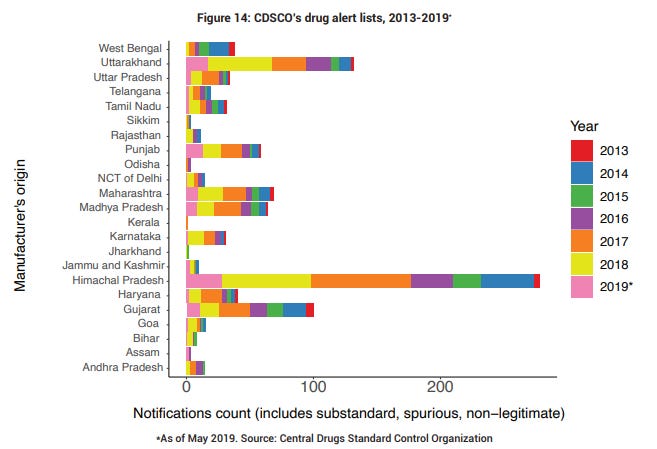

See, every medicine has two components: the core active pharmaceutical ingredient (or APIs) and the non-core excipients. APIs are what actually treat you — the paracetamol in your fever tablet, the antibiotic that fights infection, and so on. Excipients are everything else: the fillers, binders, solvents, and flavorings that hold the drug together and make it consumable. A drug usually contains a small amount of the core API, but a lot more of excipients.

In a cough syrup, for instance, the API might be a small amount of dextromethorphan, while excipients include glycerin, propylene glycol, water, and flavoring agents. These excipients are generally industrial chemicals that are often used in other non-pharma factory processes as well.

Now, most pharma R&D focuses on developing APIs. Such attempts fail very often, but they’re usually caught at the R&D stage itself in routine quality control tests. Since the API is the active core of the drug, it gets plenty of attention by the regulator. In fact, India imports most APIs, and pharma imports are strictly governed by the Centre.

But, the larger risk lies with the excipients. They are used at the manufacturing stage to mix with the APIs — so they can only be spotted on the factory floor. India has not given adequate attention to excipients as it has to APIs, and that has been a major blindspot.

See, the standards for excipients and APIs are set centrally. However, there is a lack of specific regulations on excipients. In fact, for a long time, there was no official guideline on how much of an excipient can be used in a drug. And until last year, brands were not forced to put key information about excipients on their product labels. Think about it: you would have no way of knowing how much of a toxic item was present in your cough syrup.

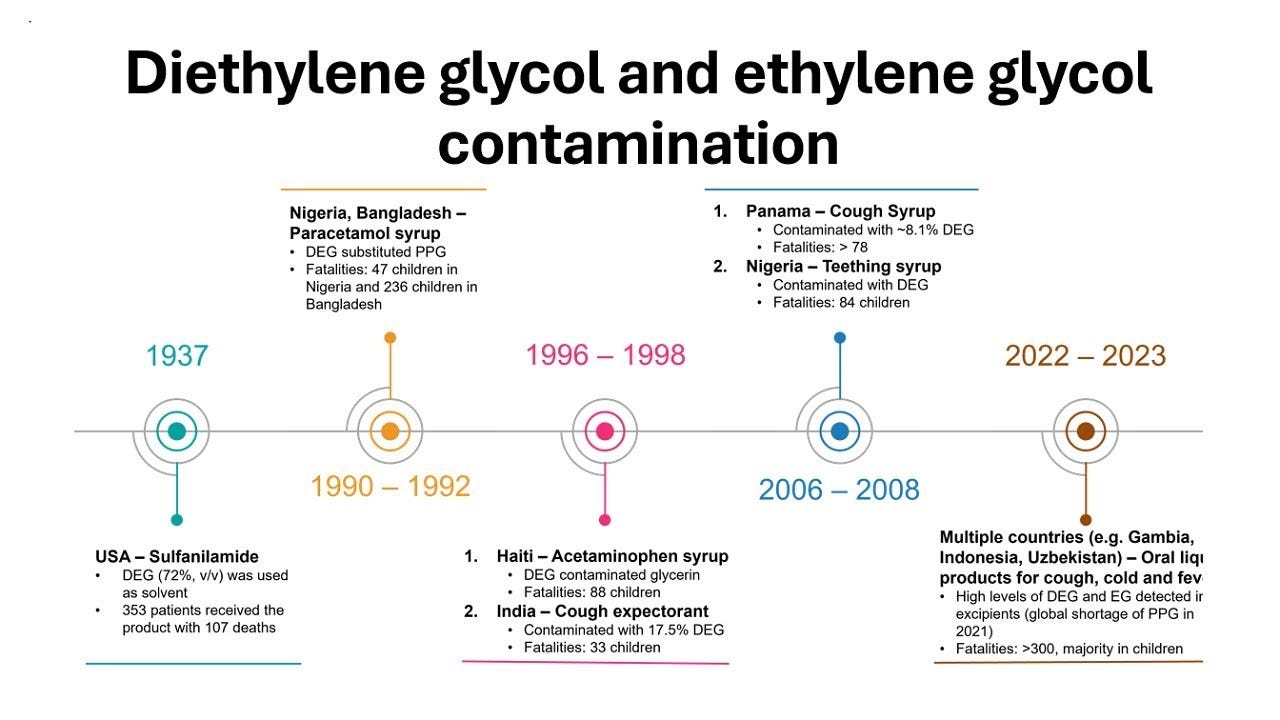

Let’s take the example of the Gambia incident in 2022. Here, the drug was found to have two toxic ingredients: diethylene glycol (DEG) and ethylene glycol (EG). DEG/EG are often found in cheaper forms of glycerin, which is commonly used as an excipient. In fact, DEG/EG poisoning has been common in other countries in the past. Yet, shockingly, despite this history, the Centre simply did not mandate DEG/EG testing in drugs until this incident.

Alongside our legal framework, our supply chains also fail to oversee excipient quality properly. Unlike APIs, excipients are often sourced domestically from commodity chemical suppliers who face far less scrutiny. To save costs, a supplier might substitute, say, pharma-grade glycerin with cheaper DEG-laced glycerin. A manufacturer might not have enough resources to test samples. However, the onus of ensuring compliance with IPC’s excipient rules lies not with the supplier or the contract manufacturer, but the brand.

The supply chain problem gets worse when you consider how low-quality drugs move between states — with a brand in one state and a manufacturer in another (and maybe a supplier somewhere else). Only host states have the power to revoke licenses, as well as approve excipients. They can’t oversee processes in other states — nor can the Centre.

While India has focused much of its rule-making towards excipients over time, enforcement continues to be very uneven across states. In fact, despite the DEG/EG testing mandate existing since 2022, DEG poisoning was yet again the cause of the children’s deaths in Madhya Pradesh last year.

Moreover, since the Gambia incident, India now operates under a regulatory model with split personalities. That’s what we’ll get into next.

Two roads diverge

India gained “pharmacy of the world” status by becoming an export powerhouse in generic medicines. However, global scrutiny threatened this reputation. After all, we were deciding the medicine rules of many poorer nations that imported our cheap products. Since then, we have taken action, but mostly only for medicines leaving the country.

Since late 2022, exports of many high-risk medicines — like cough syrups, biologics, vaccines and so on — have been directly governed by the CDSCO. India was partly forced into taking such action due to the WHO’s oversight. Moreover, the drug administrations of nations that import our medicines, like the US and the EU, are extremely strict about drug approval.

However, the rules for drugs sold within India hardly changed. A cough syrup made in the same factory now faces far tougher scrutiny if labeled for export to a different country than if it’s destined for a pharmacy in Uttar Pradesh or Assam. But Indian consumers still rely on the same under-resourced, fragmented system.

This two-tier system creates perverse incentives. A manufacturer knows that export batches will face central government testing, so those must be perfect. However, that same manufacturer could cut corners for domestic medicines, just because it doesn’t expect to be caught by the state authorities.

A much-needed correction

The story of how India became one of the world’s most powerful pharma industries is almost magical. We were hailed as the savior of poorer nations who couldn’t afford expensive Western medicines. Pharma is one of the brightest spots in Indian manufacturing, even as we struggle to scale other sectors.

But, throughout our tale of triumph, the quality control of Indian medicines has always been a prickly thorn. In the absence of a tight framework, Indian companies have often fabricated data about the quality of their drugs. The most infamous such case, Ranbaxy, ceases to exist independently anymore. And they’re all part of the same systemic problem. Our state capacity, legal infrastructure, and supply chains have often brought us down.

In many ways, these issues resemble the early days of any country trying to scale up manufacturing — think “Made in China” once being a symbol of poor, copycat products. However, for Indian pharma to not be stuck there, the next phase of industry evolution cannot avoid fixing how we test our medicines.

Tidbits

Telcos clash with Adani over mobile networks at Mumbai airport

Reliance Jio, Airtel and Vodafone Idea have urged the government to intervene after Adani’s Navi Mumbai airport allegedly blocked telecom operators from installing mobile network equipment. Telcos say the move creates a monopoly bottleneck, while Adani denies the charge and offers a “neutral host” network instead. Passenger complaints over poor mobile coverage have surged since the airport opened.

Source: ReutersIndia’s unemployment rises to 4.8% in December

India’s unemployment rate edged up to 4.8% in December, from 4.7% in November, according to government data. The increase points to a softening labour market even as economic growth remains strong, raising questions about job creation keeping pace with expansion.

Source: ReutersRBI recognises FEDAI as forex market self-regulator

The RBI has recognised FEDAI as a self-regulatory organisation for authorised dealers in the foreign exchange market. FEDAI has one year to align with RBI’s Omnibus SRO framework and expand membership, a move aimed at improving conduct, transparency and oversight in India’s forex market.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Manie.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Hey team - thanks again for the stories. Wanted to share a research note that you guys might like to explore - https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/the-central-bank-balance-sheet-trilemma-20260114.html.

Useful read... thanks for no noise article