Is this the End of Cheap Chocolate?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Climate change hits your favourite treat

Unraveling a stock market scam

Climate change hits your favourite treat

Barry Callebaut, the world's largest chocolate manufacturer, announced this week that it was cutting its sales volume guidance for the second time this year. The Swiss company, which processes nearly 2 million tons of cocoa annually, cited "unprecedented cocoa volatility" as the primary reason for reducing its outlook.

This announcement marks a significant moment in what has become the most severe cocoa crisis in over six decades. What started as localized weather problems in West African cocoa farms has evolved into a global crisis affecting everything from farmer livelihoods to chocolate bar prices at local grocery stores.

The cocoa market is collapsing

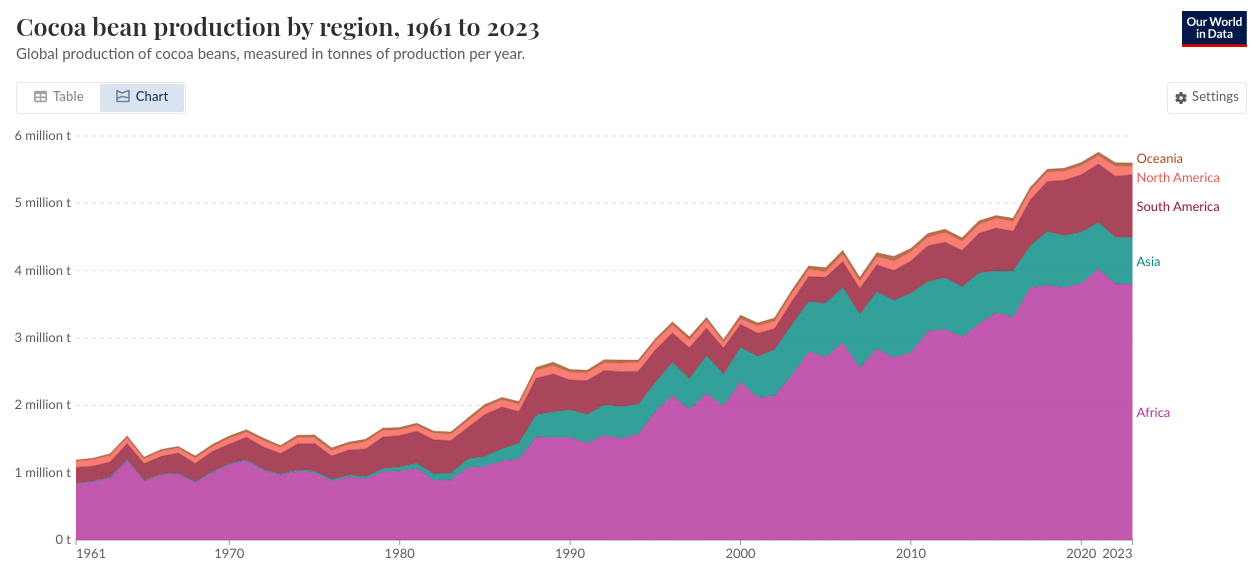

Global cocoa production declined by 13% in the 2023/24 season to 4.368 million tonnes, while demand remained steady. This created a supply deficit of 494,000 tonnes — the largest shortfall in more than 60 years.

Just to put that into perspective, it is basically equivalent to losing the yearly cocoa output of Ecuador, the world's third-largest producer.

The production collapse was most severe in the world's two largest producers that produce 60% of all cocoa — Ghana and Ivory Coast:

Ghana's cocoa production reached only 531,000 tons in the 2023/24 season, while its average hovers around 800,000 tons. This season is Ghana’s worst performing cocoa bean production session over the past 15 years.

Ivory Coast's production fell by about 20% to approximately 1.8 million tons, down from an average of 2.25 million tons annually in recent years.

Combined, both countries lost more than the entire global shortage

There aren’t enough cocoa reserves in the world right now. The cocoa-to-stocks ratio, a key indicator of market tightness, suggests we have less than two months of consumption. Usually, the markets require a three-to-four buffer for stable prices.

And what happens when demand is high and supply is tight? Cocoa prices rise dramatically.

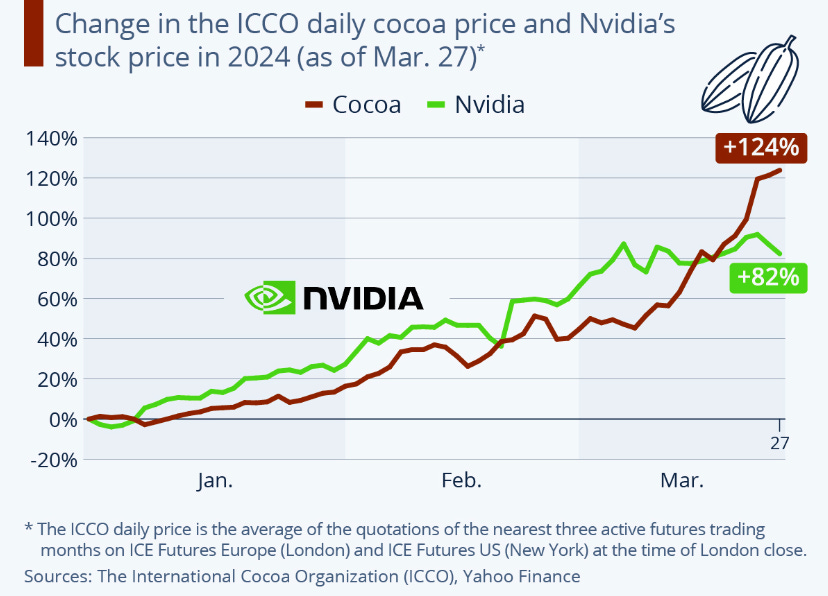

Futures contracts reached wild highs of $12,931 per metric ton in December 2024, more than four times from typical levels of $2,000-$3,000 per ton. At its peak, a kilogram of cocoa became more valuable than precious metals of the same weight.

For two years back-to-back, cocoa prices have risen far more than every major commodity. While gold rose 25% in 2025 and oil prices had modest gains, cocoa's meteoric rise has made it the standout performer in global commodity markets. Briefly this year, the percentage rise of cocoa prices even exceeded that of NVIDIA.

The International Cocoa Organization projects some recovery for the 2024/25 season, with global production expected to increase by 7.8% to 4.840 million tonnes. Simultaneously, demand may decline by 4.8% to 4.650 million tonnes due to high raw material costs. This would even out demand and supply to some extent.

Analysts suggest that next year, cocoa prices will stabilize but remain elevated around $6,000-$10,000 per tonne.

Resources are being fueled into making cocoa varieties that need less water and are more resilient. The World Bank has also invested a whopping $227.5 million into diversifying its crop production from cocoa in order to minimize risks.

But cocoa’s comeback is highly dependent on the one big factor that has brought about this crisis in the first place.

Climate Change: the biggest culprit

Climate change has long been considered as the biggest threat to making cocoa. It is worsening the conditions that cacao trees, which give us cocoa, require to thrive.

Cacao trees require very specific temperatures to grow. The trees need warm conditions that aren’t too hot either. Maximum annual averages should not exceed 30-32°C, while the minimum must stay above 18-21°C.

This narrow temperature tolerance makes cacao trees extremely vulnerable to climate change. Even small increases in temperatures can push existing regions outside the optimal range, leading to reduced yields, poor bean quality, and eventually making areas unsuitable for cocoa cultivation entirely.

And that is exactly what is happening.

In Ivory Coast and Ghana, Climate Central reveals that there’s going to be 40 more days with temperatures hotter than 32°C every year. This has severely impacted the quantity and quality of harvests. By 2050, climate change could reduce global cocoa yields by 20%. West Africa could potentially lose half of its cocoa-producing regions as it gets hotter.

And climate change isn’t just making areas hotter. Rainfall has become more volatile, too.

The 2023-24 season was particularly devastating due to the El Niño weather phenomenon. West Africa has swung violently between periods of extreme rainfall and severe drought. In December 2023, total precipitation in West Africa was more than double the 30-year average, followed by a scarcity of rain in 2024. This pattern of alternating excess and scarcity has made production of cocoa unstable.

Climate change has also exacerbated the spread of devastating plant diseases that threaten cocoa plantations. For example, Black Pod Disease emerges due to the humidity created by too much rain followed by hotter conditions. It can destroy up to 80% of farmers' crops. Cacao Swollen Shoot Virus Disease affects approximately 20% of Ivory Coast’s cocoa and accounts for 15-50% of harvest losses in Ghana. Ghana has launched the biggest viral eradication effort ever attempted to combat this.

Beyond climate change, several other problems have made the cocoa crisis worse:

Illegal gold mining, called "galamsey" in Ghana, has become a major threat. Farmers lease their cocoa farms to miners for quick cash. This destroys the land permanently, making it impossible to grow cocoa again.

Meanwhile, many cocoa trees are simply getting old — some plantations are way past their prime productive years, but farmers lack the money to replant new, healthier trees.

Despite record-high cocoa prices, farmers still receive very low payments due to government price controls. High costs for fertilizers eat into their thin profits. This gives them little incentive to re-invest in farms or replant new trees. Some farmers have even started smuggling their cocoa across borders to find better rates.

Young people are abandoning cocoa farming entirely, seeing it as unprofitable hard work.

Beyond Cocoa

Cocoa is one of many crops that climate change is destroying. Major food crops worldwide are facing similar struggles. If they continue to do so, we could be facing food insecurity at a global level in the not-so-distant future.

Maize, for example, has the highest production among grain crops. But it is very sensitive to heat stress. If greenhouse emissions are consistently high, yields of maize might drop by 24% by the latter part of this century. And it will affect everyone from North America to East Asia.

Wheat and rice serve as a dietary staple for billions of people. But wheat yields are projected to decrease by 19% by 2050 and up to 40% by 2080 in India alone. And rice yields are expected to decline by 20% by mid-century in many regions, including India.

Soybeans are an important source of protein for both humans and animals. Global soybean yields could fall by more than 11% by the end of the century under even moderate warming scenarios. Yields can decrease by 4% for every 1°C increase.

The bottom line is clear — climate change is reducing the world’s capacity to produce food at scale. For every degree the planet warms, global agriculture loses about 554 trillion kilocalories. And each person loses 120 calories per day, while they should have 2,000-2,500 calories daily. That’s extremely worrying.

Here’s another way to put it: if temperatures rise by 3°C, the caloric loss would be like a whole population skipping breakfast every day.

The Broader Implications

The cocoa crisis is the most visible example of how climate change is reshaping global commodity markets and supply chains. The unequal distribution of impacts — with smallholder farmers bearing the greatest production risks while receiving the smallest share of profits — highlights inequities in global agricultural systems. These structural problems are likely to worsen as climate pressures intensify, potentially creating new sources of instability.

The question is no longer whether climate change will disrupt our ecosystem. It already is doing so. The question now is how global action must proceed to maintain food security and economic stability.

Unraveling a stock market scam

In the last few months, SEBI has been on a roll, increasing its vigilance on fraudulent schemes. In what could be one of its biggest crackdowns yet, SEBI is stepping up its investigation into a large pump-and-dump scheme involving shell companies.

One recent case involves just a single day of trading in KPIT Technologies, and a little-known firm called Mehrangarh Financial Advisors Pvt Ltd (MFAPL). On the surface, it looks like just another profit-making intraday trade. But SEBI’s order shows it was actually a front-running operation carried out by MFAPL. They somehow knew that a large client was going to sell KPIT, and used that to their benefit. Also involved in this was the brokerage Anand Rathi.

The profit in this case was just ₹19.53 lakh – fairly tiny relative to more famous scams. But this isn’t about how big the scam is. It’s all about the structure — how a firm places trades ahead of a big client’s order, how people inside brokerages use that information, and how it all plays out on the exchange within seconds.

We’re covering this story to show you how front-running actually works — in real time, with real trades.

What’s front-running?

Front-running is when someone places trades based on confidential information about a large client order that hasn’t yet been executed. If you know a big client is going to buy, you buy first. If you know they’re going to sell, you sell first. When the client’s large trade moves the price, you profit — at the expense of everyone else.

And, of course, this is illegal.

What happened in the KPIT case

On July 26, 2017, MFAPL made an intraday profit of ₹19.53 lakh by buying and selling shares of KPIT Technologies.

This is how the trade unfolded, within all of 2 hours:

- Before 10 AM, Anand Rathi received a ₹100 crore buy order from an institutional client called Warhol Ltd

- Between 10:00-10:35 AM, Vishal Laddha from Anand Rathi and IIFL's Rishad Lalla arranged a bulk deal - matching Anand Rathi’s buyer with Warhol Ltd's plan to sell KPIT shares

- From 10:13-11:10 AM, MFAPL sold 5.52 lakh KPIT shares at ₹123.73 average price. 95% of sales occurred after the Warhol deal was confirmed (but not executed) at 10:35 AM

- At the opportune time of 11:11 AM, MFAPL placed a buy order for the same 5.52 lakh shares at ₹120.20 - far below market price

- At 11:24:06 AM, Warhol's sell order was executed. Merely 2 seconds later, at 11:24:08, MFAPL's buy order was matched

- In the matter of a few minutes, MFAPL made ₹19.53 lakh profit by selling high and buying low

This kind of setup — sell first, then buy back at a lower price after a large sell order hits the market — is known as a Sell-Sell-Buy (SSB) pattern. SEBI accused MFAPL of illegally finding out about Warhol’s sell order in advance.

Who was MFAPL?

On paper, MFAPL had two directors: Naresh Chandra Bohra and his mother, Shakuntala Bohra. But SEBI found that the company was not truly independent. It was operated and funded by entities and employees of the Anand Rathi group.

Here’s what SEBI found:

Bank transactions showed that all the funds in MFAPL’s accounts came from Anand Rathi group companies.

The email ID and phone numbers linked to its trading accounts belonged to Anand Rathi employees.

The people who operated and authorised MFAPL’s accounts also worked at Anand Rathi.

MFAPL was later merged into another Anand Rathi group company in 2018.

SEBI concluded that MFAPL was a front entity — a shell used to carry out trades based on privileged information.

How did SEBI find out?

Interestingly, SEBI’s order doesn’t say how the trade was flagged. There’s no mention of a whistleblower, a client complaint, or an internal alert. But SEBI decided to investigate the case in March 2019, nearly two years after the trade happened. The Investigating Authority itself was appointed in 2020.

The trade may have stood out during a standard data review. It was a large trade, and too precisely timed. But officially, we don’t know what triggered the investigation.

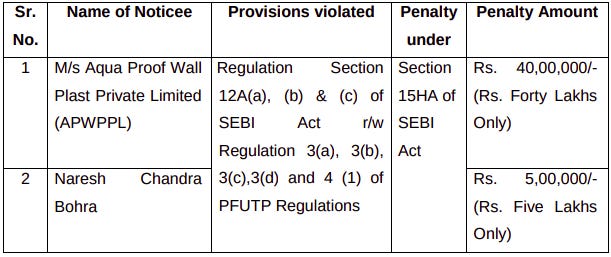

MFAPL (now APWPPL) was fined ₹40 lakh and its director Naresh Chandra Bohra was fined ₹5 lakh, totaling ₹45 lakh.

Tidbits

We had looked into the Q425 results of life insurance companies. We have some new data which could shed some light on how Q126 results might look.

India’s life insurers clocked a 4.25% rise in new business premiums (NBP) in Q126 — a slowdown from last year’s 23% jump post-regulatory changes.

LIC grew premiums by 3.4%. Its margin constraints continue, thanks to heavy reliance on low-margin participating policies. HDFC Life led private players with 14.5% growth. SBI Life maintained margin discipline, but posted just 3.3% growth, likely due to a shift away from low-margin ULIPs. ICICI Prudential’s 6.4% growth hints its pivot from ULIPs toward guaranteed products may be taking hold — but the impact on margins will be clearer in coming quarters.

Source: Business StandardWe recently wrote about how India’s auto sector is facing the heat from China’s rare earth export curbs. That heat’s now turning into action.

With magnet shipments still stuck at Chinese ports and Indian EV plans under stress, local players are scrambling for solutions. Mahindra & Mahindra and Uno Minda are now exploring local rare earth magnet production — a critical step toward self-reliance.

The government, too, is pushing for this shift. Incentives are reportedly in the works, and plans to build strategic stockpiles and expand domestic mining through IREL are gaining momentum.

Source: Business LineThrough the results of major FMCG companies, we saw that growth is slowing in the space. Could a new CEO shake things up?

Hindustan Unilever has appointed Priya Nair as its new Managing Director and CEO, effective August 1. Nair, who has been with the company since 1995, currently leads Unilever's €13 billion beauty and wellbeing division and will succeed Rohit Jawa, who steps down after over 37 years with the company.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Prerana and Krishna.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Scared to read, As it was like Interstellar storyline we are losing out our crops. but here there is no bulk being help us. we have to find a solution and take action now!

Instead of:

"Before 10 AM, Anand Rathi received a ₹100 crore BUY order from an institutional client called Warhol Ltd"

You meant:

"Before 10 AM, Anand Rathi received a ₹100 crore SELL order from an institutional client called Warhol Ltd"