Is AI cannibalizing smartphones and laptops?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Is AI cannibalizing personal computing?

Decoding the Fractal Analytics IPO

Is AI cannibalizing personal computing?

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, AI models are moving at lightning-speed. But today’s Daily Brief isn’t really about that.

Instead, we’re looking at a second-order consequence of the boom. Due to AI’s insatiable demand for resources, the consumer electronics you’re already familiar with are being rattled.

For instance, Apple CEO Tim Cook expects the cost of making iPhones to increase very soon — primarily because memory chips are being diverted from phones to AI data centers. Xiaomi, meanwhile, has basically asked consumers to brace for price increases in their smartphones. Laptops have the same problem; Lenovo, the largest enterprise laptop supplier, asked its clients to make bulk orders early before they hike prices.

In essence, AI growth seems to be coming at the direct expense of personal computing devices — like smartphones, laptops, gaming consoles, even smart glasses.

We aren’t sure what the implications of this are. Will AI kill these markets off? Will there be a new equilibrium, where AI co-exists with pricier consumer electronics? Or are there other structural forces at play?

None of these are questions that we mere nerds have definitive answers to. But merely thinking about them took us down rabbit holes that were too intriguing to not share.

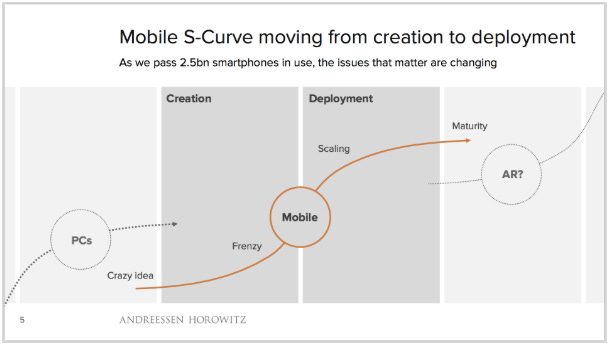

A mature technology

Before we get to AI, here’s something we’ve been noticing: the market for smartphones and laptops seems to have plateaued. These technologies have matured, and they’ve stopped being growth engines.

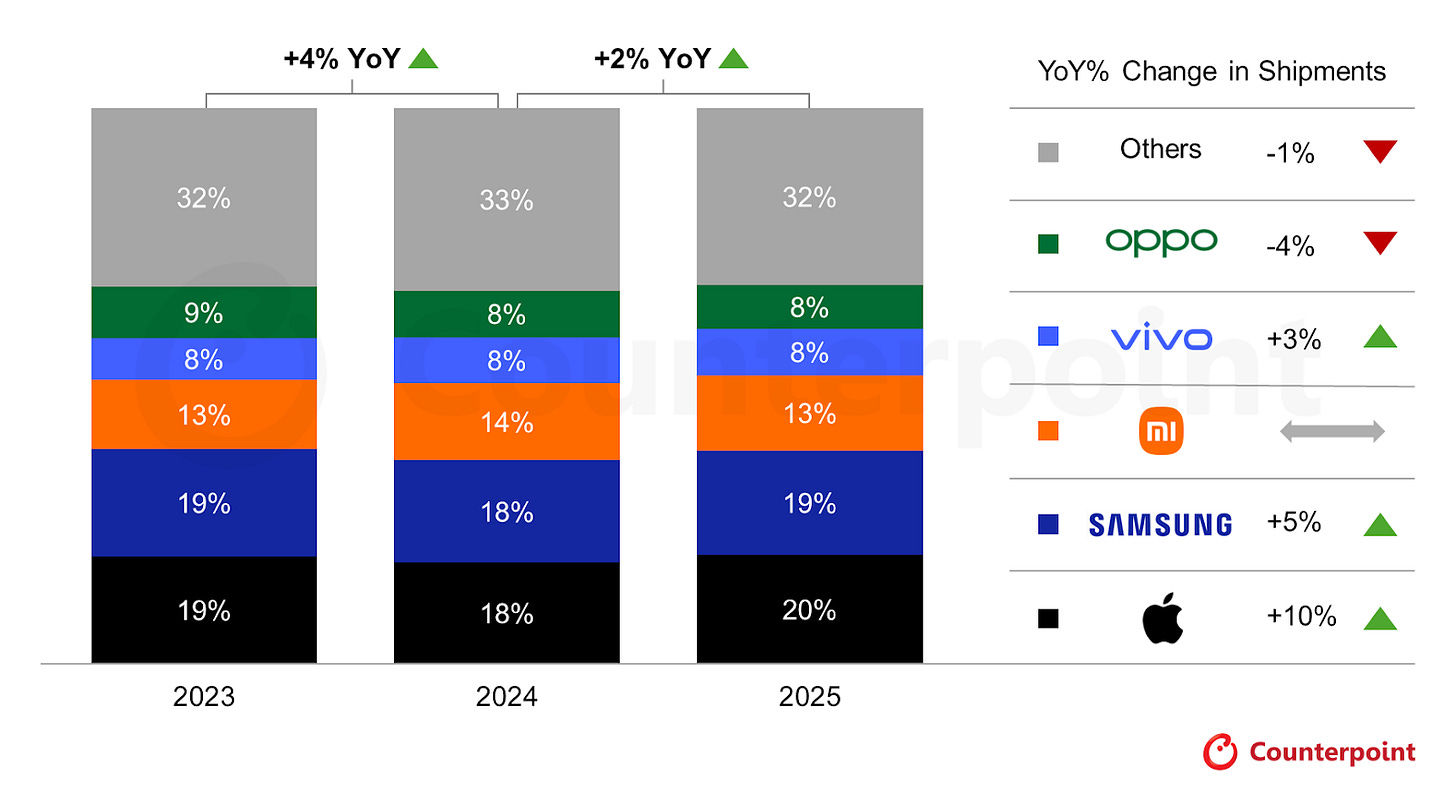

Phone sales, for instance, have been growing at a snail’s pace — probably because everyone who might need a competent phone already has one. They’ve gone through a long process of constant iteration and innovation — pushing the prices of smartphones to a point where most people in the world can purchase one. In India itself, over 85% of our households have at least one smartphone.

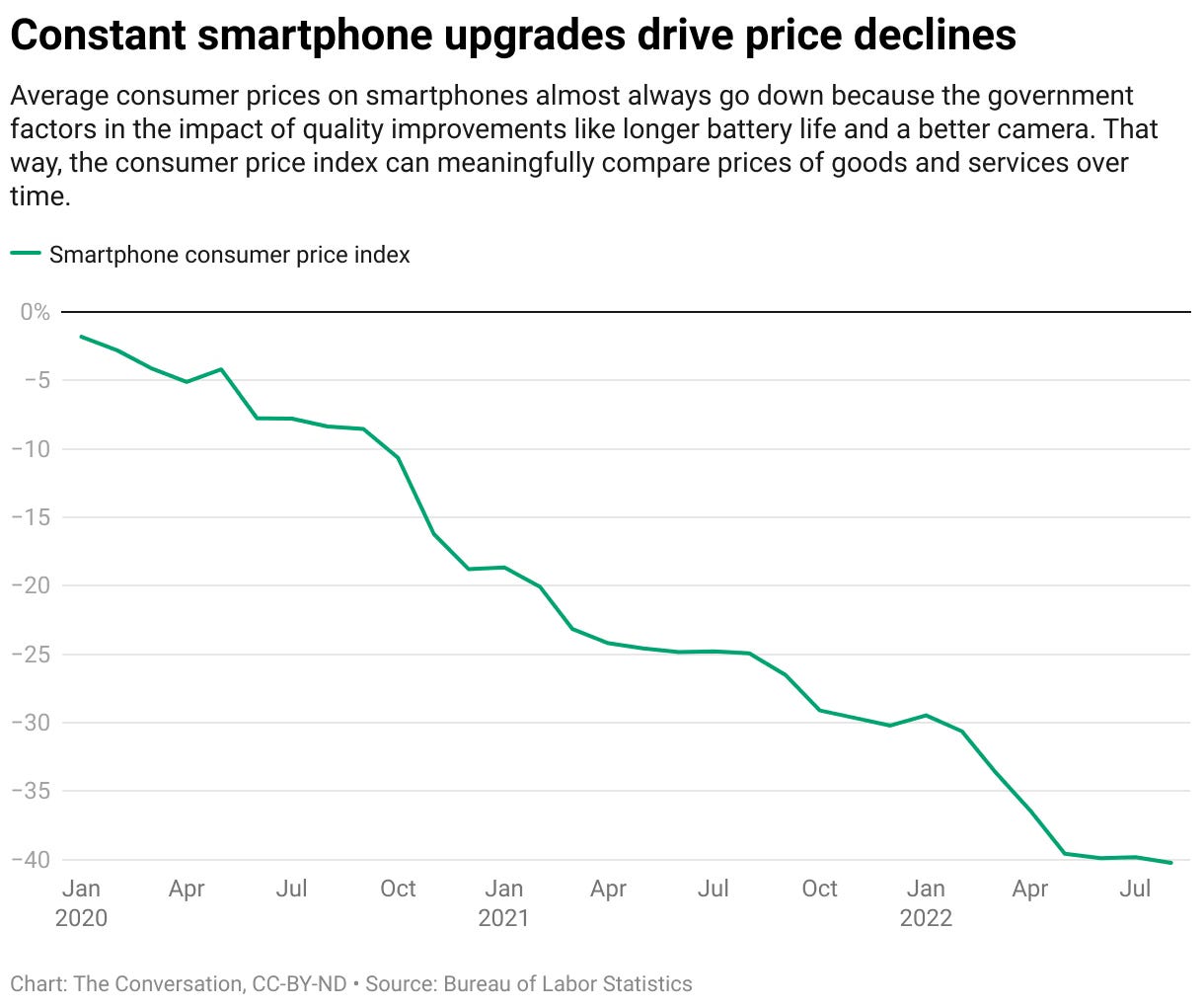

Meanwhile, even the most basic, cheap smartphone keeps notching up higher in quality. Chances are, both you and the richest person in the world use the same iPhone model. We’re nearing a point where innovation in phones is incremental; most of the transformational changes in the modern smartphone may be in the past.

For instance, one of the biggest draws for any phone Indians buy is camera quality. But increasingly, a solid camera can be found in a ₹15,000 phone just as well as one that costs 3 times more.

The story is similar for laptops. Even cheap laptops, today, can play most games, edit videos fast, and run multiple tasks at the same time with ease, all while lasting longer than ever. It isn’t obvious that there’s space for fundamental leaps.

Upstream funk

In essence, the demand for consumer electronics that defined the last few decades was already slowing down. And then AI came for the supply.

(ROM)e wasn’t built in a day

We’ve previously covered the world’s memory market, and the incredible supercycle it’s currently in.

This includes memory chips, which usually means DRAM — which stores short-term, working memory. This helps your phone process a heavy application, like, say, playing Call of Duty. This memory is wiped out once the application shuts.

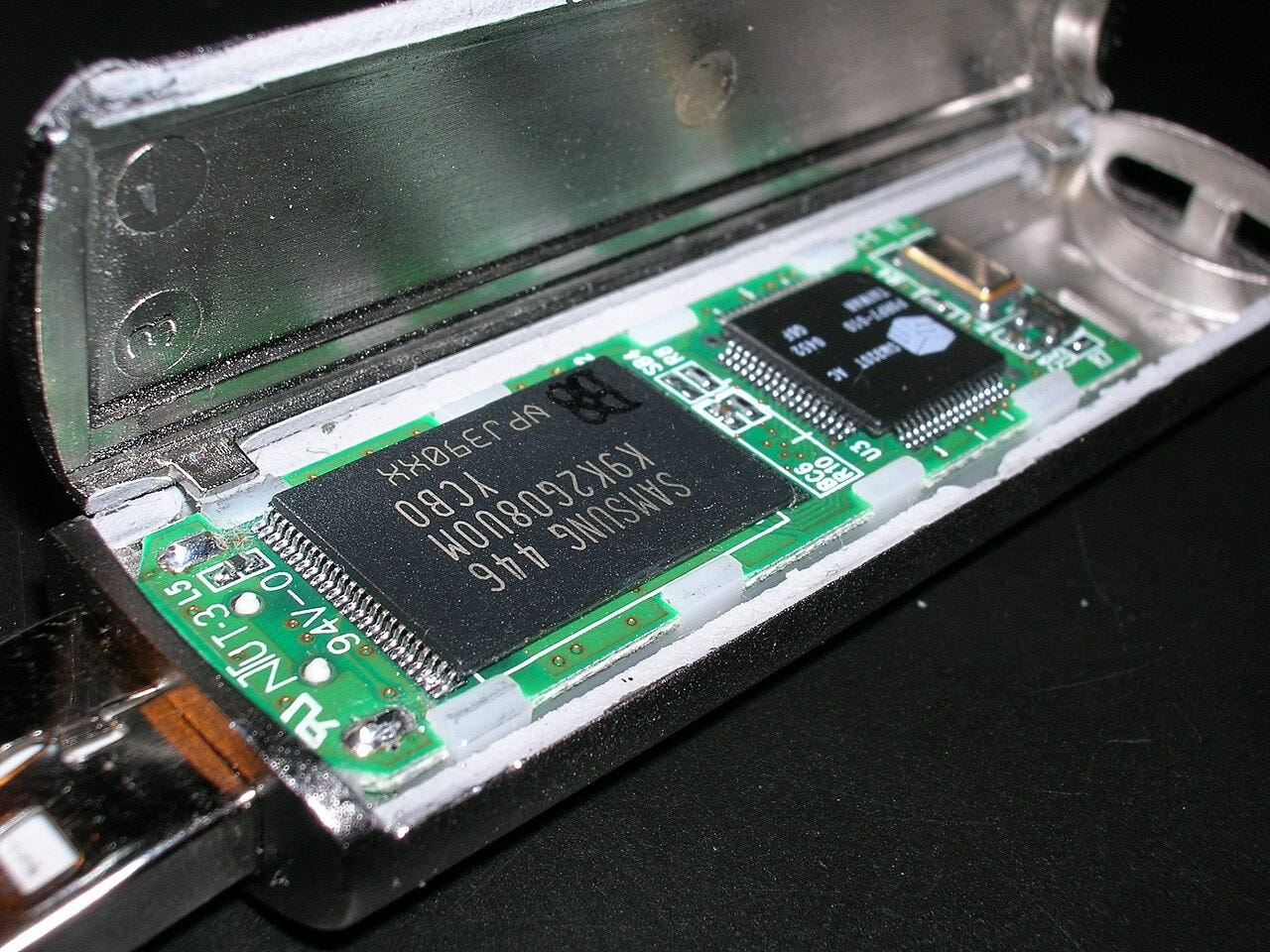

More broadly, memory also includes long-term storage devices (or ROM), where you probably still keep your favorite music and movies if you’re older than 30. This could be a hard drive, a USB stick, or — in the case of phones — NAND flash memory.

Like phones and laptops, AI also needs DRAM and NAND. It uses a special, more complex type of DRAM called high-bandwidth memory (HBM), which holds your LLM’s working memory as it processes your requests. NAND, meanwhile, is where the actual weights of the model live — as does all the data it’s trained on.

Where’s all that memory chip capacity to serve this exploding new industry coming from? Well, companies are diverting their existing capacity, built for phones and laptops, towards AI.

See, building a memory chip plant is incredibly costly and takes years. Meanwhile, the memory industry is extremely volatile, swinging between oversupply and excess demand. Rarely does it strike a balance. This is an industry where few can predict what will happen just a couple of years into the future. The history of this industry is littered with companies that got their long-term bets wrong, over-committed investment for demand that never came, and died out.

So, memory chip-makers are usually conservative with capex. Re-tooling is a cheaper and faster way to meet demand.

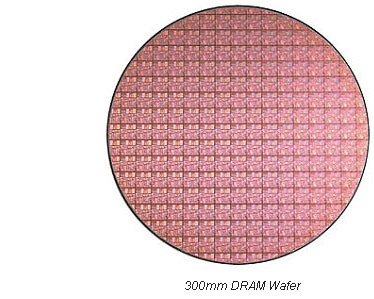

It’s not just plant capacity, though. DRAM chips of all kinds share similar inputs. For instance, they use wafers — ultra-thin slices of silicon, which are stacked to create a DRAM chip.

However, silicon is a rare commodity, as are wafers. Every wafer that’s used in a laptop is one wafer less that goes into a high-bandwidth memory chip. Companies would rather choose the more profitable option. Smartphones and laptops no longer have the margins where they can out-compete AI, which offers stratospheric rewards.

Perhaps no company truly showcases this trade-off better than Samsung. Its Galaxy line of smartphones is one of the most popular in the world. It is also one of the world’s biggest memory chip makers. However, the memory division declined a long-term DRAM deal with the phone division. Samsung knows all too well that their memory business is, on some level, cannibalizing their phone business — and is willing to live with it.

Advanced packaging

Memory is only part of the AI resource crunch. Another important, under-appreciated bottleneck is advanced packaging.

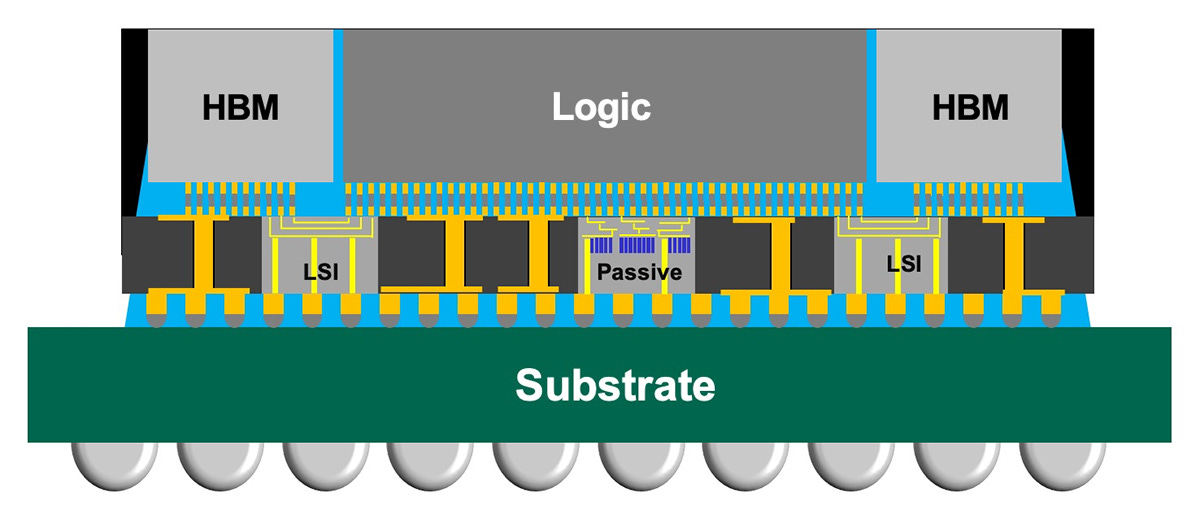

For any computing device to work efficiently, it’s not enough to just have processors and memory. The two units also have to be connected close to each other. The closer they are, the faster data flows between them. However, it isn’t as easy to just keep them close to each other. Both HBM and GPUs generate tons of heat that could damage the entire module that houses them, unless its cooling is managed properly.

This is ensured by advanced packaging. The packaging technology that AI uses is called chip-on-wafer-on-substrate (CoWoS) — where its processing and memory units are placed within mili-meters of each other, with millions of connections tied together.

Modern-day phones and laptops don’t really use (or need) CoWoS. But they have their own packaging needs, and they compete with AI for the same packaging infrastructure. New capacity is expensive, and expansion often isn’t viable. And like with memory chips, the raw materials for packaging technology are often the same.

The bottomline is that, at many levels, the capacity and raw materials for AI and consumer electronics are shared. And in a world where smartphone and laptop sales were already slowing down, it makes more sense to divert to AI.

Replacing the screen

Where does this train stop? Are the consumer devices we use — the one you’re reading this on — already outdated? Could the AI wave eventually replace the devices themselves, with new devices for this new era?

This question is a bit of a leap, we know. Our bet is that nobody really has an answer.

There have been some attempts to answer that question. Only, they have so far been failures.

Take, for instance, the R1, built by the startup, Rabbit. It was a “pocket companion” that ran a custom AI-centric operating system — neither Android, nor iOS. It was designed to direct AI agents to do many things at once for you. Theoretically, for instance, it could book a cab on Uber for you, without you even seeing the app.

In practice, though, people didn’t find it too different from… well, a smartphone. It didn’t even run basic voice commands properly. It was terrible at booking that Uber cab.

There’s also the Humane AI pin, launched by ex-Apple employees. It was a device you could wear on your chest and operate with voice commands. Sadly, the device was unable to even perform basic phone functions, hardly able to meet its initial hype.

The race for the next big computing form factor is still on. The big labs are all in on this race. Reportedly, OpenAI is building one. Meta, of course, has its AI-powered smart glasses. Google is making its own wearables play.

But this is a hard race to win. To go toe-to-toe with a smartphone, a new form factor needs to be many things at once — it has to have many uses, a great battery life, strong cybersecurity, a great camera, superb call quality, great sound, and so on. Today’s phones are close to being all-in-one devices. Why, then, would we want to ditch them?

Co-existence, coherence

The alternative is that phones and laptops are supplemented by AI: with AI becoming the biggest feature people look for within phones and laptops? That’s the trajectory AI seems to be on, today. Phones and laptops are incredibly personal devices. AI hasn’t meaningfully changed their roles in our lives. Maybe, AI supplementing consumer devices is just what consumers want.

The modern architecture of AI services revolves around centralized cloud servers, with phones and laptops serving as interfaces to those servers. Phones and laptops, in a sense, are a ready-made distribution layer for AI services.

As a result, many AI services today are being designed around smartphone or laptop applications. Claude Cowork, for instance, will neatly organize the files on your Windows or Mac desktop automatically, without you having to move the cursor yourself.

Some of the biggest phone brands are already making huge bets on this reality — following two approaches:

One, bolting on AI

In this approach, AI is integrated into specific features or tasks, but not at a system level. It doesn’t control your phone, nor can it easily do tasks that require many steps. That is, AI only streamlines your existing workflows, but doesn’t shape them itself.

Samsung’s Galaxy phones, for instance, have built many task-specific AI enhancements, like translating a video call in real-time, or creating realistic images out of sketches, and so on. But broadly, they still work like the phones we know.

Two, AI-native devices

A newer approach is one where AI is integrated into the system logic. That is, it isn’t just limited to specific tasks — but can access the whole system. It can interpret your goal, based on some broad prompt, and figure out the best way to get there autonomously, even decide its own workflows. In short, it’s an agentic device.

Take ByteDance — the parent company of TikTok. Along with ZTE, China’s largest state-owned telecom operator, it created the Nubia M153 phone — powered by ByteDance’s own LLM, although it otherwise runs on Android.

Interestingly, it’s able to do a lot of multi-step tasks, based on a simple audio prompt. Ask it to buy something, for instance — and it might look for it, compare the best prices across retailers, and push the order through for you. It could also make restaurant bookings for you without you opening an app.

This is almost revolutionary. Perhaps that’s why it sold out on day 1 — faster than any attempt at a new form factor.

But the device came with one massive problem: privacy. Many companies that owned individual apps were uncomfortable with the lines that ByteDance’s LLM breached. Meanwhile, some Nubia users couldn’t log into their own apps. ByteDance, then, was compelled to pull back its AI integrations.

And that’s probably the biggest danger with this approach: it’s extremely invasive.

Conclusion

For the foreseeable future, phones and laptops aren’t going anywhere. They might get a bit pricier, and AI will likely seep into them, but the fundamental device remains. Plus, right now, most companies are looking to shape these devices as vessels for AI services.

But, AI has shifted the economics of consumer electronics. There is little incentive for phone makers to pay obscene amounts to procure memory chip capacity, especially as their sales are plateauing. But AI firms are more than happy to make those payments. That, currently, has decided the outcome of the upstream battle.

The downstream battle, though, might only be beginning.

Decoding the Fractal Analytics IPO

Over the past couple of years, and especially more recently, we’ve seen a lot of noise around AI eating the internet world. And according to some of the louder takes, AI is also the death of Indian IT.

But at the same time, we’re seeing something that doesn’t quite fit that narrative. A bunch of mid-cap IT firms are out there talking about strong, sometimes surprisingly high, revenue growth in this very same period. That tells you something important is happening under the surface. We’ve talked about it before.

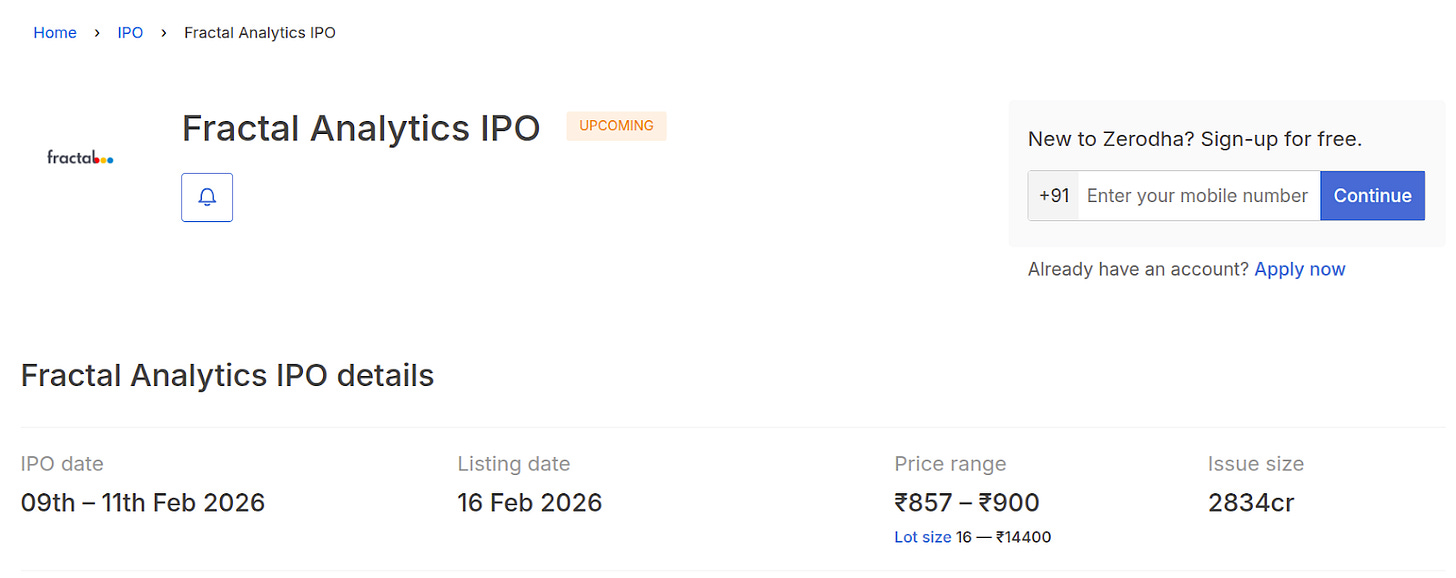

It’s against this backdrop that a new upstart, Fractal Analytics is coming to the market with an IPO.

At first glance, it’s easy to bucket Fractal as just another services firm with AI slapped onto the pitch deck. But we think that’s a lazy way to look at it. This is one of those cases where a bit more nuance actually matters.

And this isn’t just about analysing one IPO. Understanding Fractal is really an attempt to make sense of how mid-cap IT is evolving, what kind of work is growing, and where AI actually fits into all of this, beyond the hype and the hot takes obviously.

So let’s start.

From “keeping the lights on” to “telling you what to do next”

Let’s start with the basics.

For the longest time, when we spoke about IT services, it broadly meant one thing: helping large businesses digitize their operations. And digitization could mean a lot of different things.

It could mean fairly standard stuff — application development, maintenance, and so on. It could also mean cloud services: migrating systems to the cloud, maintaining them, and making sure they don’t break. It could also mean cybersecurity — building systems to protect data and infrastructure. All of this sat neatly under “IT services.”

The common thread across all of this is important. These services were fundamental to running a business, ensuring these new systems were smoothly integrated — and compliant — with business operations. But Fractal doesn’t vibe with that.

Instead, it places itself in a category called DAAI services — short for Data, Analytics, and AI services. If traditional IT services were about running business operations, DAAI is about decision intelligence.

Let’s say you’re a company that sells protein bars. You have data on customers that tells you how often they buy, where they’re located, and so on. But how do you use that to decide what your product should look like, its pricing, or which stores should stock more of it at what times? And if any of the decisions you’ve taken on these questions don’t work as intended, how should you change your plans?

That’s where Fractal says DAAI steps in. It helps clients run simulations that estimate the probability of different outcomes, test decisions, and keep iterating as real-world data comes in. In practice, this involves applying a lot of statistical methods, like regressions, root cause analysis, etc. And increasingly, to improve the quality of predictions, machine learning and AI are being used to run complex, behemoth-scale statistical models.

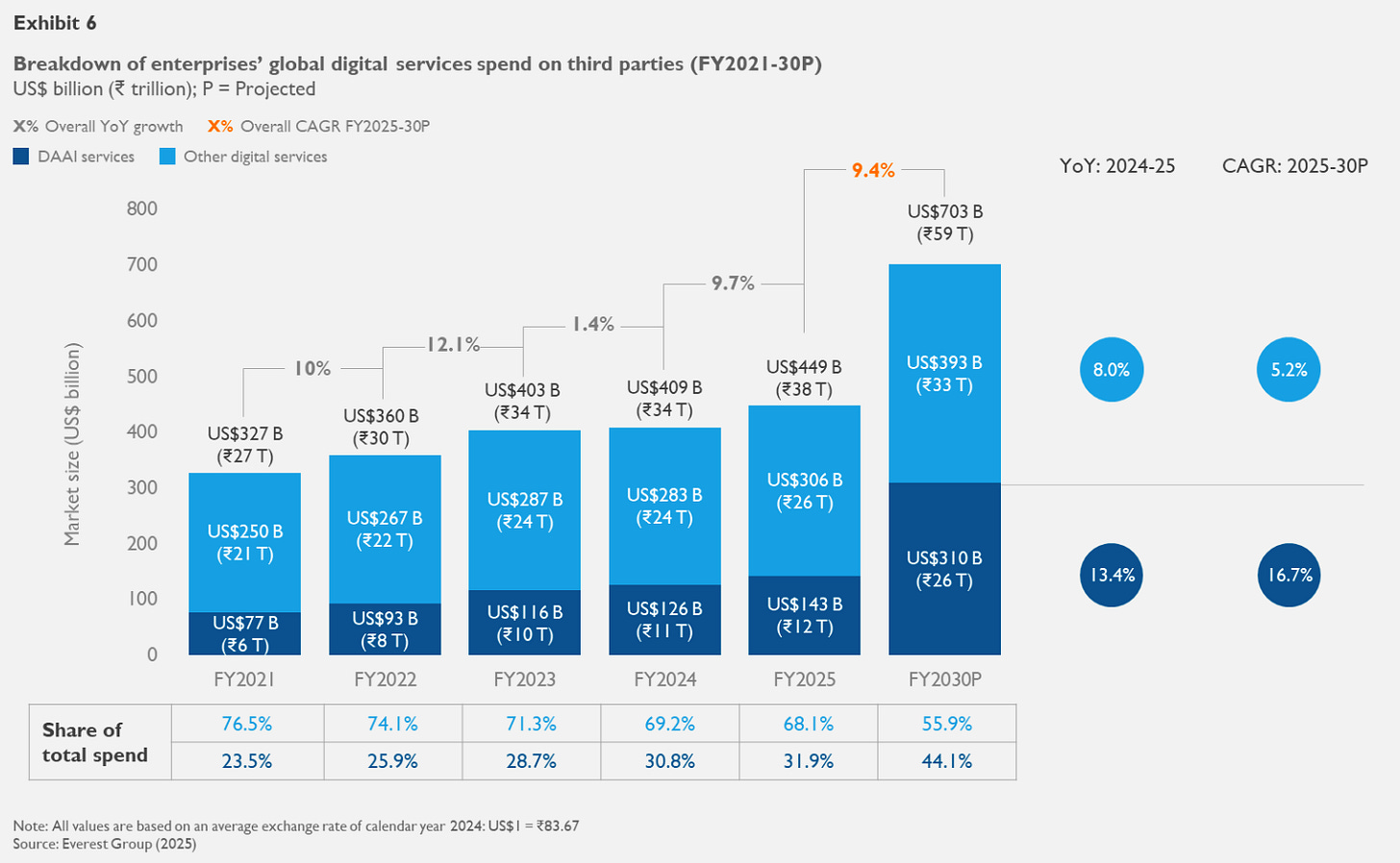

As per industry estimates, the DAAI market has grown faster than that of other IT services, with the growth rates only diverging further.

That shift also changes how value is measured. In traditional IT services, success is often measured by how many man-hours have been logged into a project. In DAAI services, the focus moves away from that and towards outcomes.

An important nuance that differentiates DAAI from traditional IT is who the buyers actually are.

In the AI and analytics services market, the buyers are overwhelmingly large enterprises. More than 70% of the demand comes from companies with over $5B in revenue. And the reason is pretty simple: DAAI services tend to be more discretionary than typical “keep-the-business-running” IT work. For smaller enterprises, that kind of spend often feels harder to justify. Larger enterprises, on the other hand, have both the budget and the scale to invest in it.

That alone changes how this industry behaves. DAAI work doesn’t split cleanly across vendors. A vendor for managing its data, while another for building models and finally someone to deploy it — these are too tightly linked to be fragmented. If you try to stitch together different partners, it gets messy, slow, and risky. So large enterprises usually prefer one end-to-end provider.

Traditional IT services are different. You can easily have one vendor for apps, another for cloud, another for cybersecurity, and it still works. In DAAI, that kind of fragmentation is a headache. And that’s where Fractal’s “end-to-end” pitch helps.

There’s another misconception worth clearing up here. Even though we keep using the word “AI,” the bulk of the work in this market is still not pure-play AI. Data work continues to dominate. This includes modernization, integration, transforming data, basic statistical modeling, and even making charts and dashboards. After all, client output ultimately depends on the quality of the data.

In that sense, Fractal is, at its core, an analytics company rather than a pure AI company. But modern analytics has become heavy on using ML and AI, so it would be unfair to dismiss that part either.

With that, let’s talk a bit more about the company now.

The Fractal way of doing business

At a high level, Fractal splits itself into two parts: Fractal.ai and Fractal Alpha.

Fractal.ai is the main engine which does DAAI work for enterprises. The DRHP does spend time describing the products embedded in this service line. But what’s missing is the one thing investors actually care about: how much revenue comes from these products, and whether this “product” revenue is genuinely separate or just bundled into services deals.

That distinction matters because if a product line is real, it can turn into recurring revenue through licenses and subscriptions — very different economics from services. Right now, there’s just no clean visibility on that.

Then you have Fractal Alpha, which is basically their “optionality” bucket. The idea here is to incubate new AI businesses, like Asper.ai and Qure.ai, in the hope that one or two of them turn into future growth levers. These sit as subsidiaries/associates, but they’re currently loss-making.

So where does that leave us?

Even if Fractal is positioned in the DAAI category, the business today is still services-first, and not a product business. There might be product optionality over time, and there might be value in these incubated bets. But neither has clearly materialized into a predictable, recurring profit stream yet.

Now, how does Fractal land clients?

Usually, it follows something called the land-and-expand model. Here, Fractal typically starts by landing inside a client with a relatively small engagement — often with a single team or function. Once they’re in, they expand horizontally and vertically across the organization, moving into more teams and functions.

For example, there was a client where Fractal initially worked with just one team. Over time, that relationship expanded to 50+ teams and more than 200 stakeholders within the same company. This model is quite common in consulting and IT services, although sometimes, the services company will land a contract with the enterprise as a whole.

This shows up in the numbers as well. Fractal’s net revenue retention (NRR) stood at 121% in FY25, which basically means existing clients, on average, spent 21% more than they did the year before. Once Fractal lands, it usually manages to expand. And these top clients are long-tenured too — the top 10 clients served have been on average for 8+ years.

But there’s a huge flip side to this model. As relationships deepen, revenue gets more and more skewed towards a smaller set of large clients. Fractal’s top 10 clients account for 54% of revenue, and the top 20 account for about 70%.

Numbers, numbers, numbers

Let’s get down to the meat of the DRHP: the numbers.

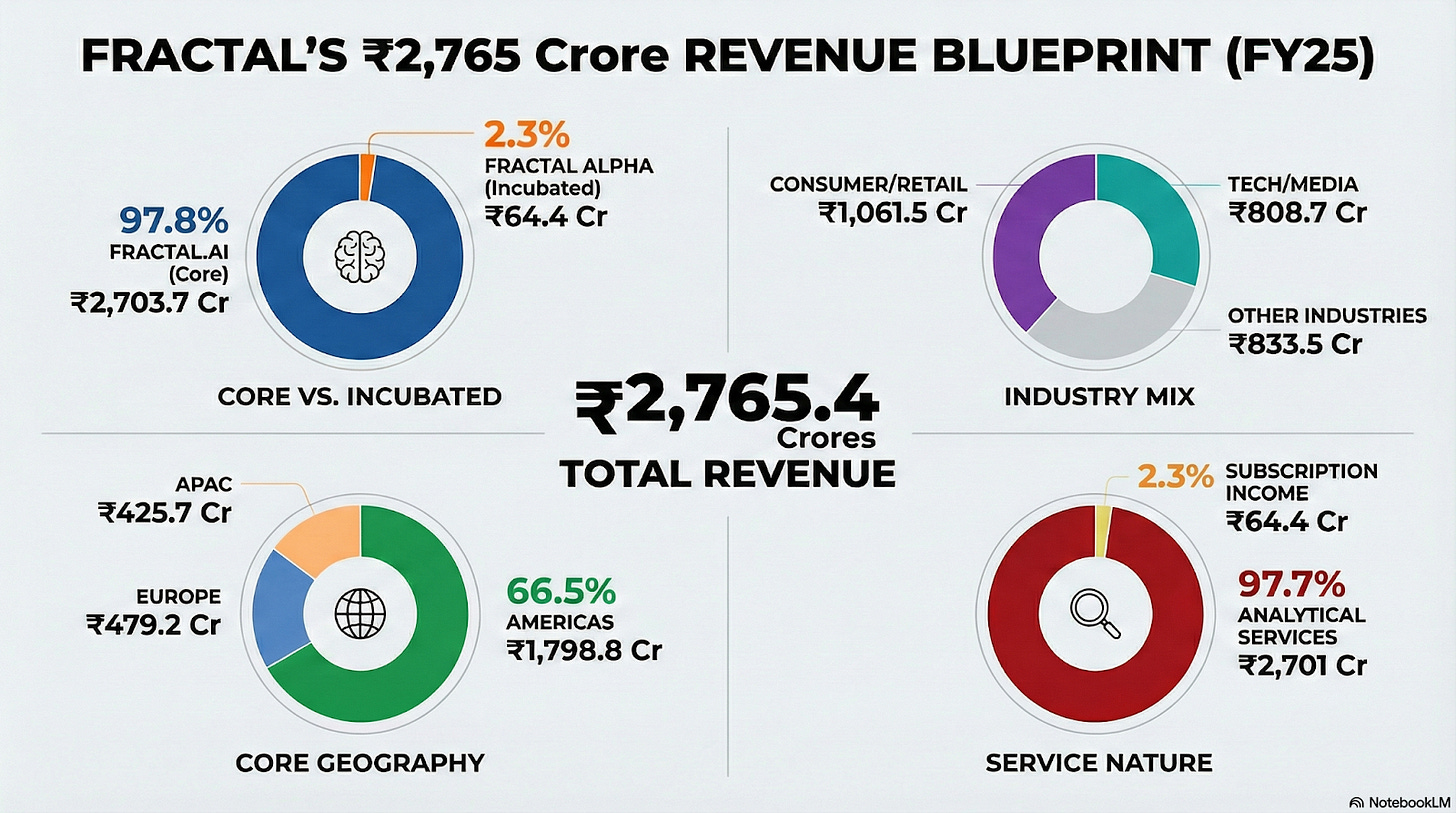

On the top line, revenue growth has clearly picked up. In FY24, revenue from operations grew 10.6%. In FY25, that accelerated to 25.9%, taking revenues to ₹2,765 crore. Even in the latest six months, growth is running at around 20%.

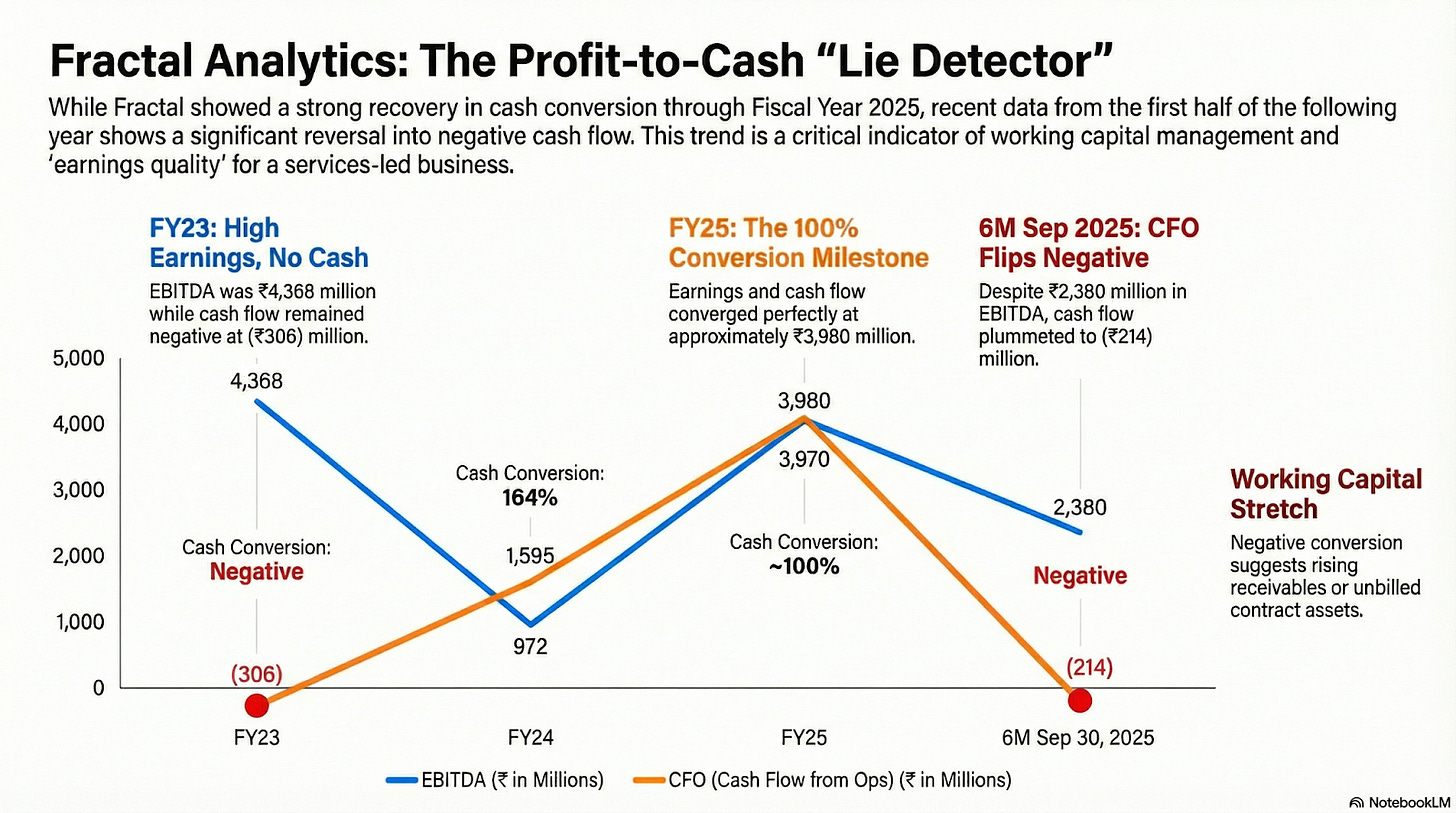

Whenever you see that kind of acceleration in a services business, the next question is operating leverage. And to Fractal’s credit, that has shown up in margins as well. EBITDA margins expanded sharply, moving from 10.7% in FY23 to 18.8% in FY25.

In terms of where the growth is coming from, it’s not narrowly concentrated in one pocket. The Telecom, Media and Technology segment — or TMT — grew 38%, while banking and financial services (BFSI) grew 28%.

Now, when you look under the hood, the dominant expense line, as with most IT and analytics firms, is employee cost. Here, the trend is clearly positive. Combined employee costs have come down from 89% of revenue in FY23 to 75.4% in FY25. Existing employees were better utilized, leading to more efficient delivery.

But there’s another cost line that needs to be watched very closely going forward: cloud and communication expenses. As GenAI adoption increases and R&D usage goes up, these costs naturally rise. On this note, Fractal made a very interesting — and somewhat funny — disclosure. They explicitly say the rate limits imposed by closed-source AI labs like Claude and Gemini has created delivery bottlenecks.

See, GenAI introduces a variable compute cost into what has traditionally been a largely people-driven cost structure. If pricing doesn’t fully pass through to clients, margins don’t expand — they either stagnate or even compress. This is a new, important dynamic that didn’t exist in traditional analytics services until now.

But, beyond costs, what about working capital and cash flow?

Yes, operating leverage improved in FY25, and operating cash flow looked strong for the full year. But in the latest six months, operating cash flow has actually turned negative. That signals a meaningful working capital drag. This happened because they paid up more payables and more money got stuck in unbilled revenue.

This is not a small issue. For a services business, how quickly revenue turns into cash is everything. Going forward, this means investors should be tracking receivables, contract assets and unbilled revenue.

The most fundamental risk to Fractal’s business, though, comes from the very thing the company wants to build itself around: GenAI and agentic tooling. As these tools get better, they don’t just create new demand — they also eat into existing services demand. Clients can start insourcing more work as AI adoption increases across the board.

Fractal actually acknowledges this risk quite clearly in its own disclosures. They point out that GenAI is significantly enhancing productivity through low-code and conversational SaaS tools. This can directly lead to revenue erosion for third-party service providers.

In such a world, Fractal’s role shifts. Instead of building and executing large pieces of the software, it increasingly moves toward just maintaining and overseeing them.

Conclusion

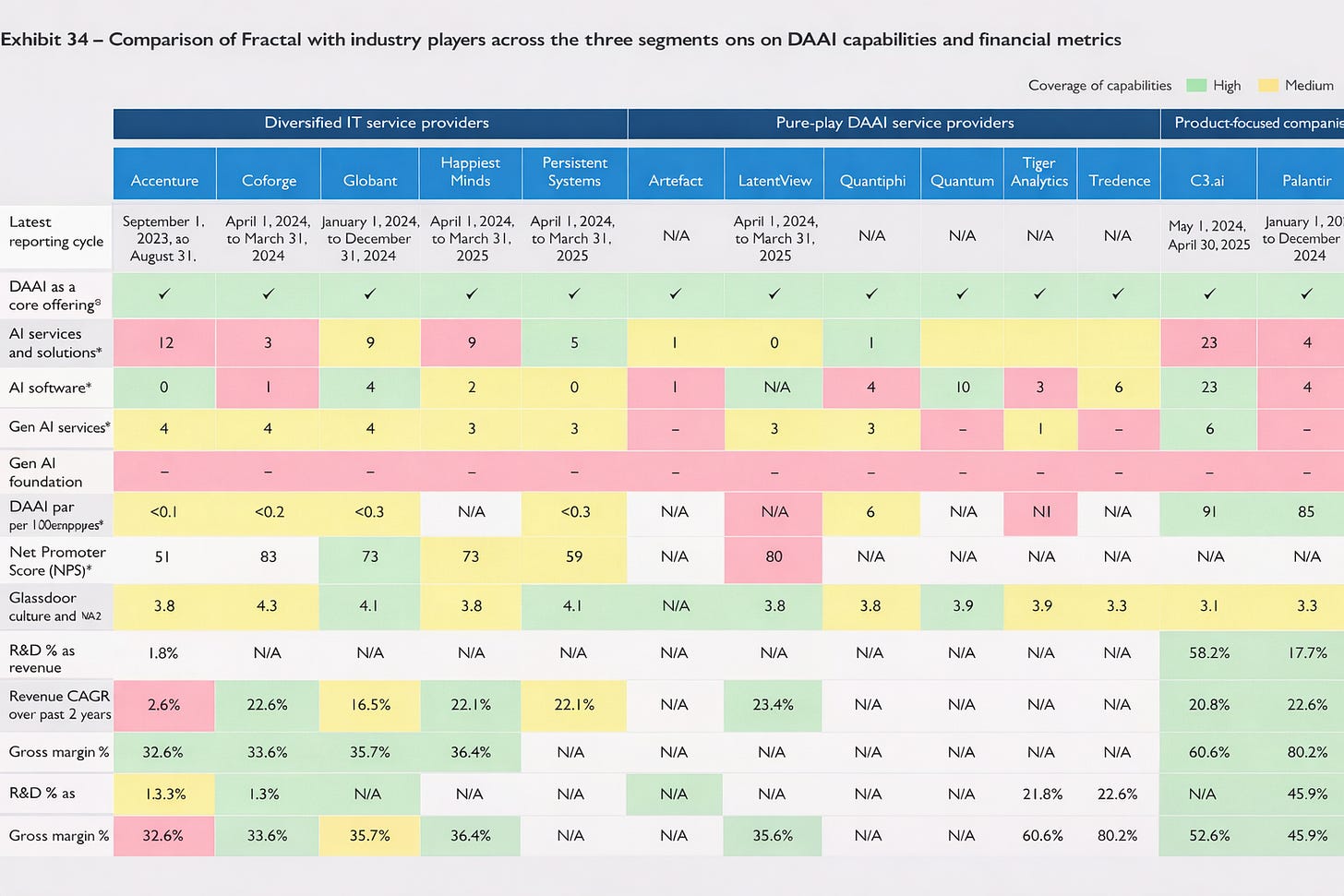

To wrap it all up, one way to look at Fractal is this: it is indeed more of an AI company than most traditional Indian IT firms. The work it does, the buyers it serves, and the problems it solves are clearly different.

But at the same time, it still carries the baggage of being a services business. It’s not as exposed to the downside risk of AI as plain-vanilla IT services, because it’s closer to decision-making and higher-value work. But it’s also not fully positioned to capture the upside of AI in the way a true product or platform company might.

Fractal lives in the in-between — part services, part AI, with some product optionality that hasn’t fully shown up yet. Understanding that middle ground is key to assessing the IPO.

Tidbits

Alphabet, Google’s parent company, expects to spend $175-185 billion on capital expenditure in 2026, potentially doubling last year’s outlay. The bulk will fund data centres, servers and AI compute capacity for Google DeepMind, as the tech giant races to keep pace in the AI arms race.

Source: CNBCVi’s ₹35,000 crore loan bid hits fresh hurdles, as lenders and banks are revising a 2024 creditworthiness study of the company. While recent AGR relief has eased near-term cash pressures, lenders remain cautious about the telco’s ₹1.25 lakh crore spectrum dues and want updated projections on revenue and cash flows before committing.

Source: MintAmazon MGM Studios is launching a closed beta programme in March for AI-driven filmmaking tools aimed at cutting costs and speeding up TV and movie production. The tools will help with tasks like maintaining character consistency across shots and integrating AI with industry-standard creative software, even as actors worry about AI reshaping the industry.

Source: TechCrunch

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Agentic device is very interesting. Wonder if there was ever a field of basic/applied science which developed at such breakneck speeds. Blink for a while and feel that you are left years behind.

Would it be possible for you folks to contrast (in charts/figures) the state of affairs year ago and today? the most optimistic/doomsday predictions and where we are today? What was felt achievable and by how much was it overshot? Hardware status then and today? This will help to gauge the rate of development in this domain.