Inside Meesho’s IPO

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Meesho IPO: The Challenger of India’s E-Commerce

How SEBI Caught ₹2 Crore Front-Running Case

Meesho IPO: The Challenger of India’s E-Commerce

For over a decade, Amazon and Flipkart shaped Indian e-retail by pouring billions into warehouses, logistics, and next-day deliveries. But now their dominance is being squeezed from two directions.

In big cities, instant-delivery upstarts like Blinkit, Zepto, and Swiggy Instamart are poaching convenience-seeking customers. High-value urban shoppers, who once might have used Amazon/Flipkart for small quick orders, are instead turning to Q-com apps for super-speedy service. We’ve written about this aspect of E-commerce multiple times.

In smaller towns and rural India, a very different threat has emerged in the form of Meesho. While the giants were busy wooing metro customers, Meesho quietly captured price-conscious shoppers across tier-2, tier-3 cities and villages. It’s the online equivalent of a DMart or Vishal Mega Mart – thriving on ultra-low prices and no-frills operations to serve the masses, representing over half of India’s new online shoppers.

Quick commerce has gotten a lot of hype for its flashy speeds and massive VC bets. But value commerce is proving just as disruptive. Meesho’s upcoming IPO shines a spotlight on this less-glamorous revolution: a mass-market, low-cost model that is fundamentally different from Amazon or Flipkart’s playbook. Today, we will talk about that.

Business Model Deep Dive

The most interesting part about studying Meesho was the different innovative ways they were solving for Indian retail, much different from traditional e-commerce players.

Meesho’s journey is a story of pivots. It began in 2015 as a platform for small sellers to set up online shopfronts, then gained fame with a reseller-driven social commerce model (think homemakers selling products via WhatsApp). By 2021, however, Meesho had reinvented itself as a more direct marketplace. Why? The reseller model, while novel, didn’t scale cleanly and people had become comfortable buying things online.

So, Meesho shifted to a zero-commission marketplace where consumers buy straight from the app, more like a traditional e-tailer.

Unlike Amazon or Flipkart, Meesho doesn’t charge sellers a commission fee at all. 0% commission on most categories means small vendors can sell online and keep 100% of their earnings. This was a radical move – Meesho essentially forgoes the typical ~15% marketplace cut to attract a flood of tiny sellers and super-low-priced products.

How do they make money then? Largely through logistics and advertising. We’ll dive into monetization soon, but the key is that Meesho’s take rate (revenue as a share of total merchandise sold) is the lowest in the industry – by design.

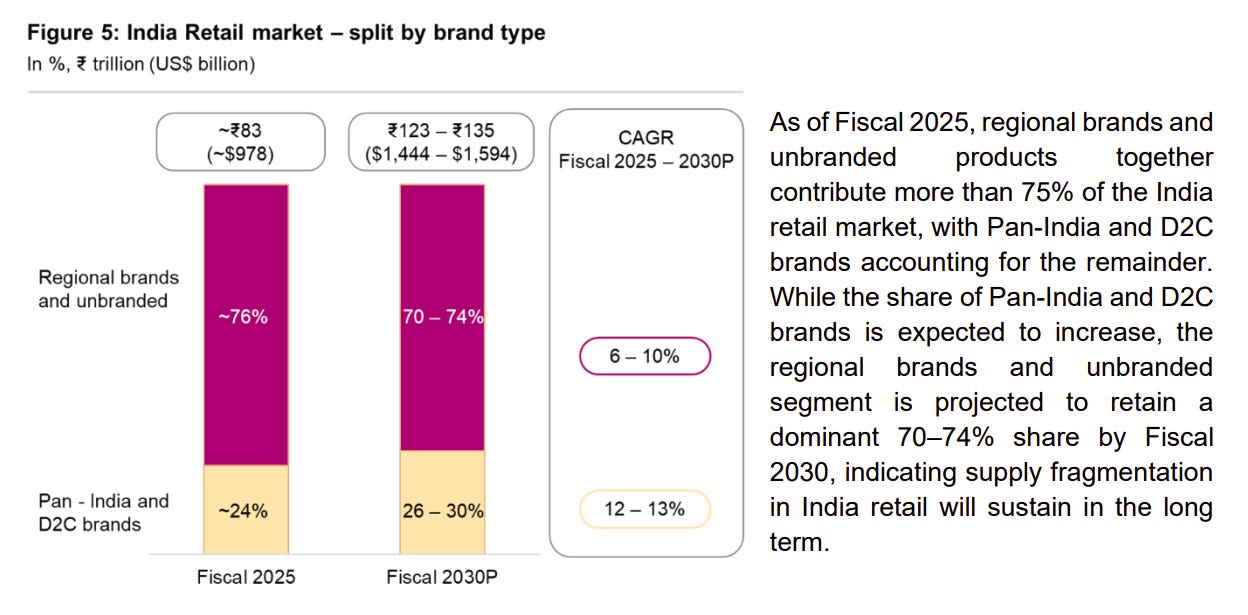

At the heart of this strategy is one realization: 75%+ of India’s retail market is unbranded or regional products, and even by FY2030 that share will be ~70%. In other words, the long tail of no-name products is the market in India, not a bug. Meesho explicitly caters to this segment.

The platform is flooded with affordable fashion, home goods, kitchen items, cosmetics – mostly made by small manufacturers without famous labels. The average order value (AOV) on Meesho is only around ₹260, which is a fraction of the AOV on Amazon/Flipkart. But that’s not a flaw – it’s the whole point.

Meesho embraces falling AOV as a growth feature: lower ticket size = more people buying more often. As the company puts it, the Meesho flywheel is all about wider assortment at cheaper prices -> more customers -> attracts more sellers -> even better prices and variety. While others chase higher spending per order, Meesho is happy to “race to the bottom” on price, because that’s where the mass market in India lives.

Today, Meesho hosts 5.75 lakh+ active sellers — mostly small manufacturers, local wholesalers, and home entrepreneurs, many without GST licenses. Over 80% of GMV comes from fragmented, unbranded supply that bigger e-coms largely ignored. Meesho built the rails for them: sellers can list and ship nationwide, while Meesho owns no warehouses, no inventory, and no private labels. It’s a pure, asset-light marketplace aggregating India’s unorganized retail online

Another piece of insight in Meesho’s different business model is that shopping in its target market is more like browsing a bazaar than searching a catalog. Over 70% of orders on Meesho come from discovery and recommendations, not from users typing in what they want. This “discovery-led commerce” mimics the offline window-shopping experience. By contrast, on Amazon you typically search for a specific item with intent. Meesho’s audience is “less intent-driven and more exploratory”, as Redseer’s research puts it.

To fuel this, Meesho is now investing in content-led commerce features. Think short videos, live streams, and influencer campaigns showcasing products. The company’s filings mention plans to integrate live streams and video shopping, creating a “shop-as-you-scroll” experience in-app. Today, content-led discovery accounts for a small but growing portion of Meesho’s sales.

Of course, a discovery-driven model has trade-offs. Engagement is high, but conversion rates and ticket sizes tend to be lower than in search-based shopping. Many people may window-shop without buying, or stick to very cheap purchases, but that doesn’t bother Meesho, but plays into its strengths.

How Meesho Makes Money

Since Meesho doesn’t charge sellers a commission, how does it earn revenue?

Short answer: by operating like a logistics and advertising company sitting atop an e-commerce platform.

1. Logistics:

Every order on Meesho runs through its system which assigns deliveries to partner couriers. Sellers pay a shipping fee to Meesho, which is a major income source. In FY25, its in house logistics arm – Valmo – handled 62% of Meesho’s orders, lowering costs by roughly 12% compared to traditional couriers. That efficiency lets Meesho keep the cost of delivery low while still earning a margin on delivery fee it charges its sellers.

2. Advertising:

Meesho also runs an ads platform where sellers pay to promote listings in search results or feeds. With millions of sellers, visibility is scarce, so ad spending is rising steadily alongside the seller base.

3. New bets:

The company’s DRHP outlines early experiments: a financial services platform (credit for sellers and buyers through partners) and expanding Valmo’s logistics services to non-Meesho merchants. These are small today but point to future revenue streams.

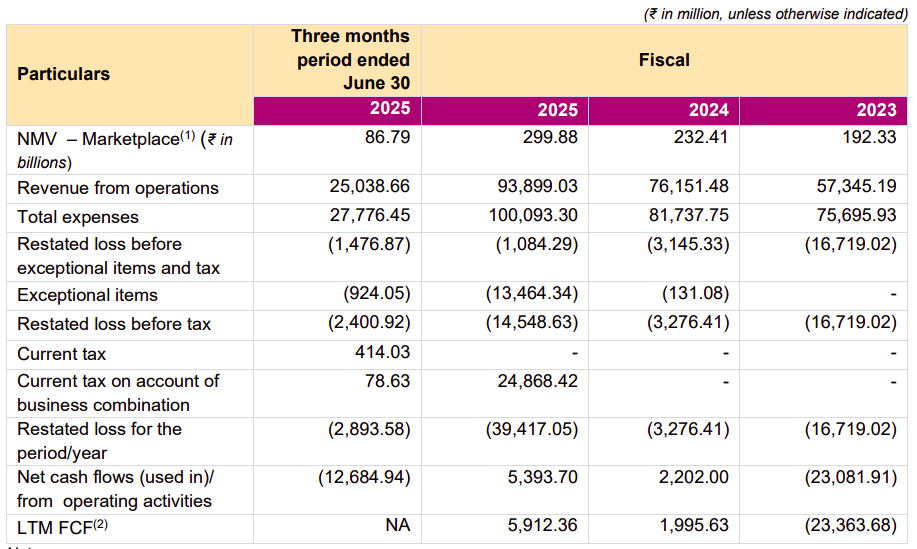

Despite having no commission income, Meesho’s monetization scale is striking. In FY25, it generated ₹9,390 crore in operating revenue on ₹30,000 crore of Net Merchandise Value (NMV) — an effective “take” of about 31%, mostly shipping-related. (For context, rivals typically earn 10–15% commissions plus shipping fees.)

Crucially, that 31% includes logistics costs — the pure marketplace commission remains zero. Yet Meesho’s model has become increasingly efficient: its contribution margin rose to 4.95% of NMV in FY25, up from 2.94% in FY23.

The payoff? Scale and cost discipline have pushed Meesho close to profitability. In FY25, it posted an adjusted net loss of only ₹108 crore and delivered positive operating cash flow for two straight years. For a zero-commission marketplace, that’s rare.

A Few Key Numbers

Over the past year, Meesho served 21 crore buyers, giving it nearly 30% of all e-commerce shipments in India. But because each order is small, its share of merchandise value (NMV) is far lower. The average order value (AOV) is just ₹274, down from last year as Meesho pushed into even cheaper categories. Management sees that as a win — deeper reach into low-income markets.

At first glance, the ₹3,915 crore loss in FY25 looks worrying. But 98% of it came from one-time accounting items — mainly a corporate restructuring and accelerated ESOP vesting for founders. Excluding those, the underlying loss was only ₹108 crore, effectively breakeven.

Operationally, the improvement is dramatic. The adjusted EBITDA margin climbed to -2.3% in FY25, from -29.5% in FY23. Meesho also generated positive operating cash flow of ₹539 crore and free cash flow of ₹591 crore, thanks to better cost discipline and working capital management. By FY25, it had stopped burning cash to run daily operations — a rarity among Indian unicorns.

A big driver was efficiency in marketing. Sales and marketing spend dropped, down from over ₹900 crore in FY23, even as user growth stayed above 20% CAGR. That suggests a powerful referral loop — existing users bringing friends and family onto the platform, rather than Meesho buying growth through ads.

Where IPO Proceeds Will Go

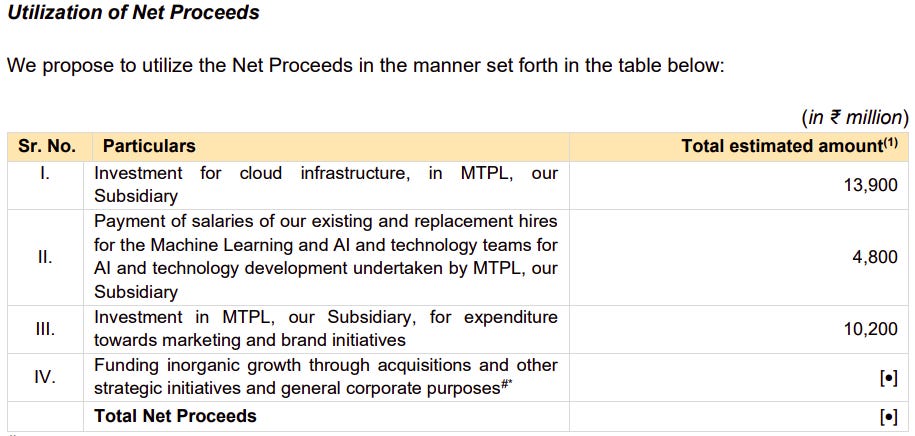

Meesho plans to raise about ~₹7,000 crore in its IPO, including a fresh issue of ₹4,250 crore. According to the DRHP, the money will primarily strengthen its tech backbone and market reach.

Cloud Infrastructure – ₹1,390 crore (~33%)

The largest share goes to expanding Meesho’s tech infrastructure — servers, cloud capacity, and hardware via its tech subsidiary. The investment, spread over FY27–FY29, will boost platform speed, uptime, and scalability, reducing dependence on costly external cloud vendors.

Technology & Talent – ₹480 crore (~11%)

Around a tenth of the proceeds will fund hiring and retention in AI, data science, and engineering. The focus: improving personalization, recommendations, and seller tools — essentially, the brainpower behind Meesho’s discovery-led engine.

Marketing & Brand – ₹1,020 crore (~24%)

Nearly a quarter of funds will go toward brand-building and outreach, especially across tier-2 and smaller cities. Expect heavier online campaigns, influencer tie-ups, and regional programs. It’s a shift from Meesho’s earlier frugality — marketing spend fell from ₹927 crore in FY23 to ₹643 crore in FY25, so this marks a fresh push.

General & Strategic Uses

The rest will go toward general corporate purposes and a war chest for acquisitions or new initiatives — giving Meesho flexibility to invest in adjacent categories or acquire niche players that complement its ecosystem.

Risks

No business is without risks, and Meesho’s model – while groundbreaking – comes with a fair share of challenges.

Price-sensitive users, low loyalty

Meesho’s customers shop for the lowest price, not the brand. If a rival — say, Shopsy or a revived Snapdeal — offers the same goods cheaper or with cashback, users could switch instantly. There’s no lock-in like Amazon Prime or exclusive brands to keep them loyal. Retention is an ongoing battle when your biggest hook is price, so Meesho must keep its deals unbeatable and experience frictionless to prevent churn.

Quality and trust concerns

Zero-commission onboarding lets anyone become a seller — great for scale, tough for quality control. Product reviews often mention mismatched items or poor durability. With mostly unbranded goods, trust depends entirely on recent customer experience. A few bad purchases can push users away, reinforcing the “cheap = low quality” stigma and driving up return costs.

Cash-on-delivery risk

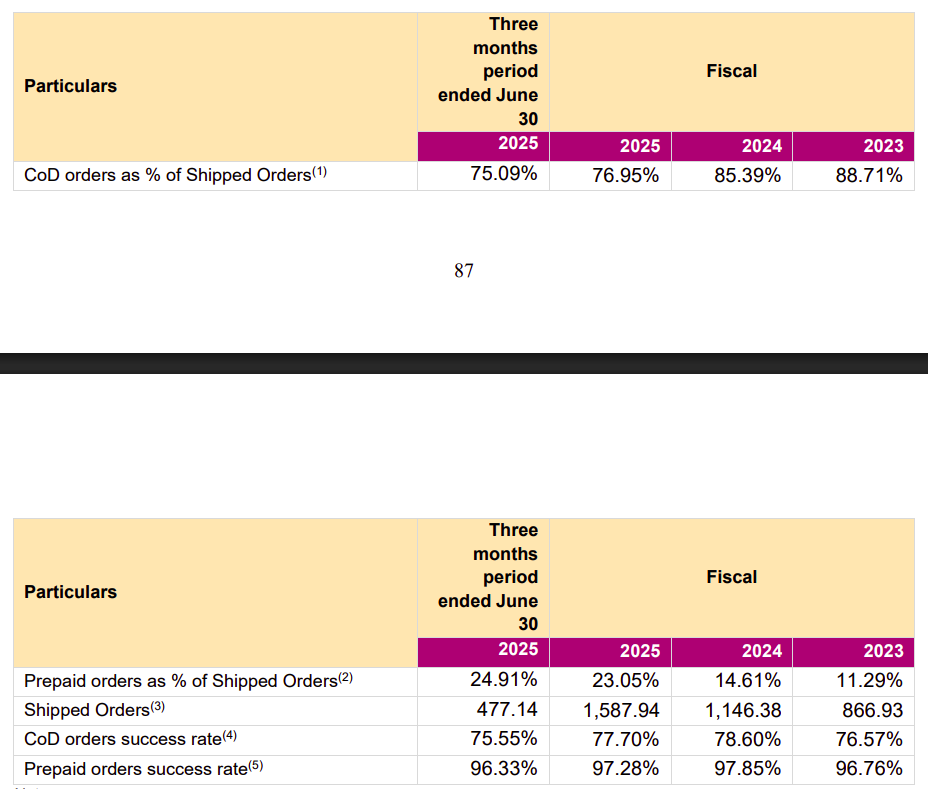

Roughly 75% of Meesho’s orders are cash-on-delivery (CoD) — and only about 75.5% of those are actually completed. Nearly 1 in 4 CoD orders fails, meaning the customer refuses or can’t be reached. Each failed delivery burns money: double shipping costs with no revenue. Even successful CoD orders add friction — cash collection, reconciliation delays, and leakage risks.

Failed orders incur round-trip shipping cost which is often a loss. Plus, for the ones that are successful, cash has to be collected by delivery agents and remitted – a process prone to leakage and delays.

Each of these challenges is manageable — Meesho is investing in Valmo, tightening return systems, and pushing digital payments — but they’re real execution tests. The DRHP devotes pages to these risk factors for a reason: Meesho’s mass-market disruption is exciting, but investors will be watching closely to see if it can sustain growth without bleeding from these cracks.

So what does it mean for the IPO?

Meesho’s IPO isn’t just another tech listing — it’s a signal that India’s e-commerce playbook is being rewritten. In a decade, this startup has built a mass-market giant by focusing on value-conscious Bharat shoppers — outselling Flipkart in order volumes while nearly breaking even.

It did so by empowering small sellers and winning buyers with ₹200 sarees and ₹100 gadgets — all through a zero-commission model that turns the traditional marketplace logic on its head. By serving the India that Amazon and Flipkart largely overlooked, Meesho embodies a new kind of disruption: one half of the market wants things faster (hello, 10-minute delivery); the other wants things cheaper — and Meesho owns that side completely.

For investors, Meesho’s IPO is more than a listing — it’s a bet that value commerce, not just convenience commerce, will power the next phase of digital India.

How SEBI Caught ₹2 Crore Front-Running Case

Recently, SEBI put out a detailed order in a front-running case where a few traders made over ₹2 crore by trading ahead of a “big client”.

Now, front-running, in simple terms, is when someone gets an early tip about a large buy or sell order that hasn’t yet been placed, trades ahead of it, and then exits once that order moves the price.

SEBI’s investigation shows how that information moved, who used it, and how the entire chain stopped trading the moment the regulator came knocking.

Let’s dive into how this particular case of insider trading worked, and how it unraveled.

Who the big client was

The investor at the centre of this case was a set of family trusts, which included: the Bharat Kanaiyalal Sheth, Ravi Kanaiyalal Sheth, and Arjun Discretionary Trusts. They traded through a partnership firm called Safe Enterprises, which acted as the execution arm for their investments. However, Safe Enterprises itself wasn’t accused of wrongdoing — they were merely the channel of investment.

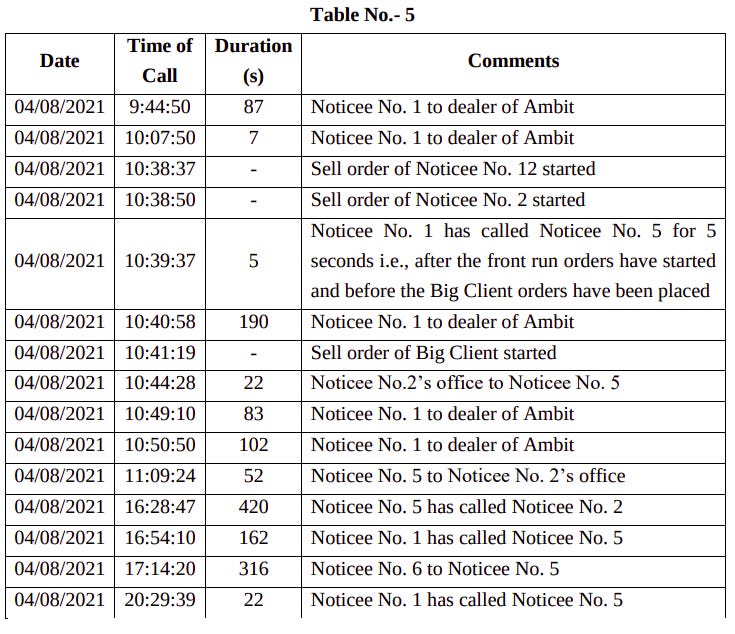

Inside Safe Enterprises sat an investment team, led by a man SEBI calls Noticee 1. He placed the orders with two brokers, Ambit Capital and Emkay Global — often staying on the phone with the dealers as the trades were being executed, and sometimes adding more quantity midway. That meant he always knew, down to the minute, which stock the client was buying or selling and how much.

That information, meant to stay confidential, became the raw material for the front-running.

How the leak happened

Now, here’s how the leak went down.

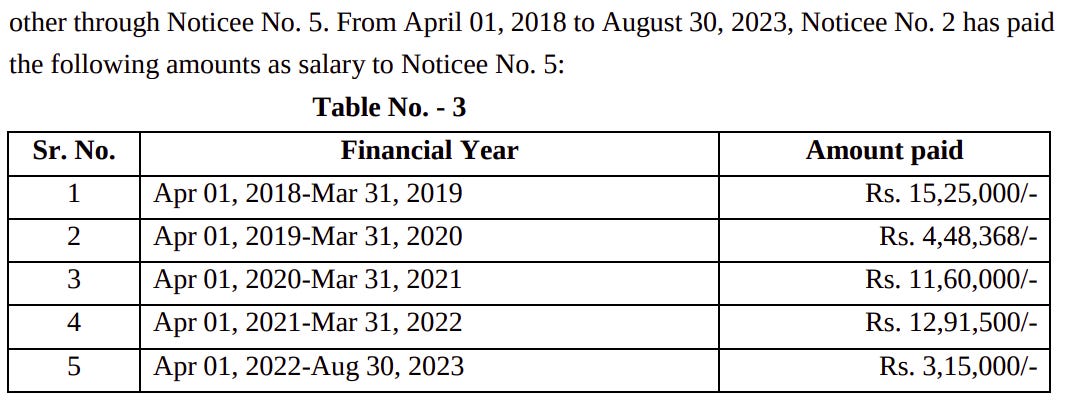

Noticee 1 was in constant touch with another trader that SEBI calls “Noticee 5”, who worked at a small sub-broker called NJK Securities. The firm was run by Jitendra Kewalramani, listed in SEBI’s order as Noticee 2.

According to SEBI, this was the pipeline: Noticee 1 shared details of upcoming trades with Noticee 5, who passed them to Kewalramani. With that knowledge, Kewalramani began buying or selling just before Safe Enterprises’ orders went out.

However, he didn’t always trade in his own name. Some orders went through his wife’s and HUF accounts, some through his employees’, and many through his clients’ accounts that he operated directly. SEBI found instances where clients admitted that he effectively ran their accounts — he decided what to buy, when to sell, and sometimes even arranged funds. In one case, money was routed through a client’s husband to bankroll the trades; in another, he sent trade confirmations to clients after the fact for them to sign.

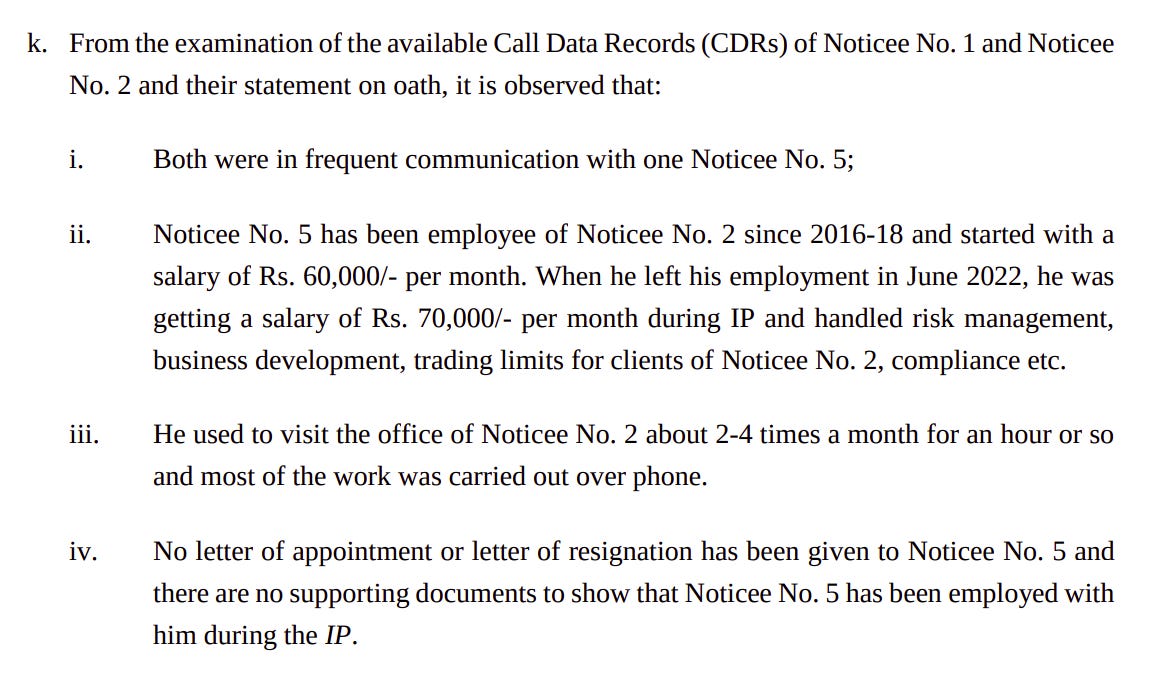

Payments between Kewalramani and Noticee 5, that were categorized as “salary,” were far larger than what their small brokerage business could justify. SEBI eventually concluded that these were not salaries at all, but kickbacks for the information being passed along.

How SEBI caught on

So, how did SEBI get alerted to this trade?

The front-running trades took place between January 2021 and October 2022. They stopped abruptly on June 29, 2022, the day SEBI sent its first query to Safe Enterprises. This wasn’t a formal investigation yet — more of a routine information check, which was maybe triggered by their market-surveillance systems.

That one query turned out to be a turning point. From the very next day, the suspicious trading pattern vanished completely.

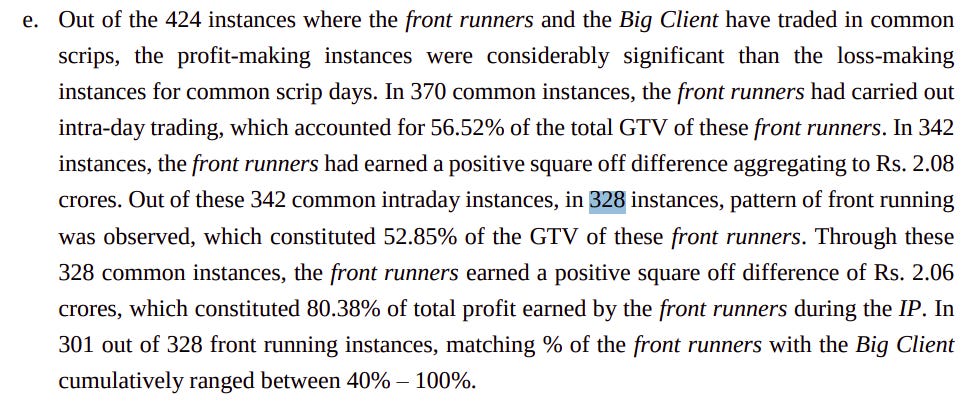

Months later, in May 2023, the National Stock Exchange formally compiled and sent its findings to SEBI. The exchange’s data showed exactly what those early alerts had hinted at: whenever Safe Enterprises placed large buy or sell orders, a cluster of other accounts traded the same stocks seconds earlier and squared off within minutes. The pattern was too precise to be a coincidence.

That’s when SEBI opened a full-scale investigation. It pulled nearly two years of order and call records — from January 2021 to October 2022 — and matched them side by side. The overlap was striking.

Take August 4, 2021, for instance. Moments before Safe Enterprises began selling a stock through Ambit, there was a short call between Noticee 1 and Noticee 5. Within seconds, Jitendra Kewalramani’s account and a few linked ones began selling the same stock. Once the big client’s sell order hit and the price fell, they bought it back immediately, locking in a quick profit.

The same sequence — quick calls, identical trades, rapid exits — kept repeating for months. Out of 424 trading days for the big client, 328 days showed overlapping trades, most lasting less than two minutes from entry to exit.

The web of accounts

Kewalramani was the hub. Around him were spokes: his employee Shankar Vadatkar and Vadatkar’s wife; his own wife and HUF; and about 13 client accounts that moved in sync with his trades.

Many of these accounts were new and fell silent after the regulator’s first query. SEBI says this behaviour is typical of proxy accounts created for a single purpose. On days when the big client traded, these accounts’ square-off profits spiked; on other days, they earned almost nothing.

In SEBI’s charts, the alignment is almost perfect: same stocks, same direction, same timing. Over those 328 days, the network made around ₹2.06 crore in total.

Safe Enterprises itself wasn’t accused of wrongdoing. It was the channel through which the family trusts placed their trades. But the insider who ran its desk, Noticee 1, had access to everything: which stock, how much, and when. Once that timing information leaked, the sub-broker’s group could mirror the trades almost instantly.

When SEBI issued show-cause notices in January 2024, the main trio — Noticee 1, Kewalramani (Noticee 2), and Noticee 5 — opted to settle. In December 2024, they paid back the entire ₹2.06 crore with 12 percent interest and were banned from the market. That took care of the insiders at the top of the chain.

The current order deals with the remaining 13 linked accounts, mostly clients and relatives who had either allowed their accounts to be used or followed Kewalramani’s trades. SEBI imposed a mix of penalties and trading bans.

The steepest monetary penalties — ₹12 lakh each — went to Swapnil Uday Shah HUF and Piyush Mehta HUF. Shankar Vadatkar, another employee in the sub-broker’s office (different from the one who settled earlier), received a ₹10 lakh fine and a three-year market ban — the longest debarment in the group.

Each has 45 days to pay through SEBI’s online portal. Until they do, their bank accounts can be debited only for the penalty amount. If they hold any open derivative positions, they’re allowed three months to close them; they can’t open new ones.

What this case shows, more than anything, is how little escapes SEBI’s radar anymore. There was no tip-off here, no confession, just timestamps and trades too perfectly aligned to be chance. A few people thought they’d found a quiet edge. All they really did was leave behind the clearest evidence of how front-running works and how quickly it unravels.

Tidbits:

Former IndusInd Bank exec settles SEBI case

IndusInd Bank’s former deputy CEO Arun Khurana has paid 50% of alleged insider trading gains to SEBI, leading to the unfreezing of his bank accounts. Khurana and ex-CEO Sumant Kathpalia were accused of trading irregularities worth nearly ₹19.8 crore that led to their exits earlier this year.

Source: ReutersReliance rushes battery imports before China curbs

Reliance Industries is fast-tracking its battery equipment shipments from China before new export controls take effect on November 8. The move aims to protect its clean energy plans as China tightens oversight on battery tech exports, crucial to Reliance’s solar and storage projects.

Source: The HinduBusinessLineStarlink begins security tests in India

Elon Musk’s Starlink has started security trials in India, a key step toward launching commercial satellite internet by early 2026. The SpaceX venture is building 10 ground stations across India—triple its rivals’—and aims to tap millions of rural users as India opens its space and satellite market.

Source: Bloomberg

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Krishna

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Excellent analysis! Love how you explained the two-directional squeeze.