Inside Amagi Media Labs IPO

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Inside Amagi’s Curious Media Model

Financing the AI boom, part #2

Inside Amagi’s Curious Media Model

The internet has enabled some strange new business models. Some didn’t exist in an offline world, and came up from scratch. Others have ripped through century-old industries, in ways nobody could have imagined.

Today, we’ll talk about an example of the latter.

There’s a company that helps run hundreds of TV channels and streaming shows for audiences worldwide. It helped bring everything from the 2024 Olympics to the US Presidential Debate to your screen. Yet, it doesn’t own any intellectual property itself. The media-tech upstart has over a thousand crores in annual revenue. This is Amagi, a vital behind-the-scenes player in streaming TV.

And it just launched its IPO.

Amagi sells the picks-and-shovels for the streaming gold rush. Today, we’re trying to understand its business, and the trends it is riding to get there.

Let’s dive in.

Explaining Amagi’s Business Model

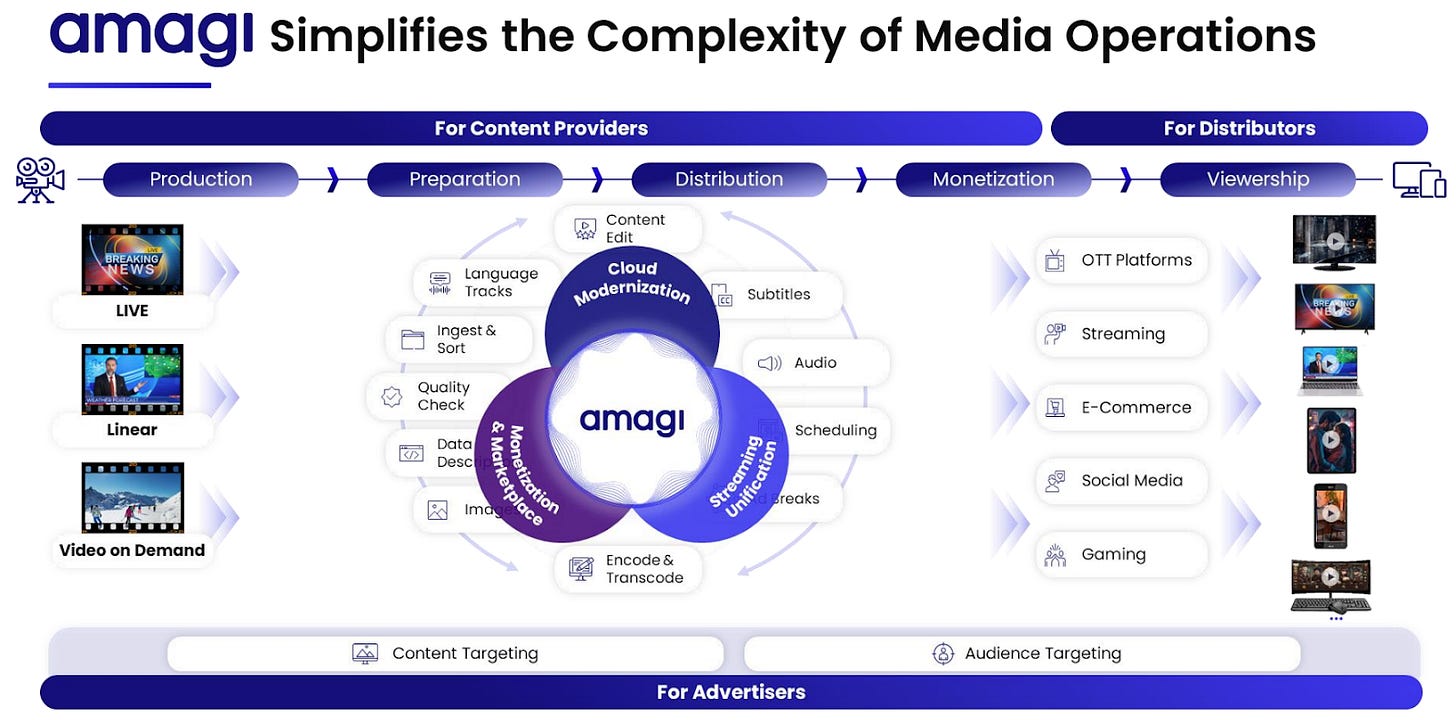

Amagi describes itself in buzzy terms in its IPO papers: as a “cloud-native B2B SaaS platform for broadcast and streaming operations”. Cutting through the jargon, though, Amagi essentially provides infrastructure to run internet TV. It has created software products that lets media companies schedule and stream their content on digital platforms, while stitching along advertising.

To understand why that’s important, though, you need a sense of the three key stakeholders in the modern “TV stack”.

Content owners (studios, TV networks, sports leagues)

First, there are businesses who own shows and live events. Their job is to bring content from their portfolio before viewers. This is a messy affair, though.

Imagine a studio that has a big library — like Lionsgate, with franchises like John Wick or The Hunger Games. It might want to push its content out, through streaming channels, on-demand libraries, or live streams. It has to contract with multiple platforms, in multiple locations. That’s a lot of grunt work — handling scheduling, subtitles, compliances, different formats, and more.

Before the internet, they would have to engage with many broadcasters or cable distribution channels, and get them to push their content. The owners of WWE, for example, would simultaneously talk to USA Network for the US, Sky Sports in the UK, Sony in India, and dozens of smaller regional cable networks elsewhere. But as streaming takes over, that giant web of relationships matters less.

What matters, instead, is technology. This is where Amagi shows up. It gives content owners software to run a “channel” on the internet: program it 24×7, schedule content, insert subtitles and ad breaks, and package the feed for different platforms. And more importantly, it helps them shift away from “on-premise” set-ups — physical systems housed within their buildings — to the cloud.

Moving to the cloud can be cheaper, sometimes meaningfully so. Industry estimates suggest that such a shift can cut total costs by ~35–50% over five years. Now, that’s an optimistic figure; the real savings depend on your scale and workloads. But it does allow modest savings, at the very least.

Distribution platforms (OTT apps, smart TV makers)

At the other end are the Roku Channels and Samsung TVs of the world, who are trying to keep viewers hooked by offering lots of channels and content to their users.

This could have been an expensive, chaotic task: where they would sign deals, one by one, with a giant ecosystem of content owners, ingest each of their feeds individually, and manage the operational mess of thousands of channels.

Amagi simplifies this process. It has integrations with 350+ distribution platforms like OTT apps and smart TV makers, giving them plug-and-play feeds. Instead of stitching together all those relationships and workflows, platforms can just tap into Amagi’s network and onboard channels.

Advertisers and ad-tech players

In essence, Amagi connects content to distribution. That lets it insert itself in between, by catering the ads.

The old, traditional TV ad tech — with fixed slots allotted in between a broadcast — doesn’t neatly fit the world of streaming. On OTT apps, ads have to be inserted dynamically, in a way that works across devices, without breaking the stream. Often, they’re specifically targeted at the viewer, based on their data. Doing this reliably is hard.

Amagi has built the plumbing for this. It handles the tech that places ads directly into a streaming channel — like those you might see pop up while streaming a show. Meanwhile, it runs a marketplace to sell those ad slots, connecting advertisers to channel owners. In between, it takes a slice of what is paid.

Tailwinds and Industry Context

In essence, Amagi sits right in the middle of the content streaming boom, as a platform that enables content to be delivered and monetized. It got to that vaulted position riding powerful industry tailwinds.

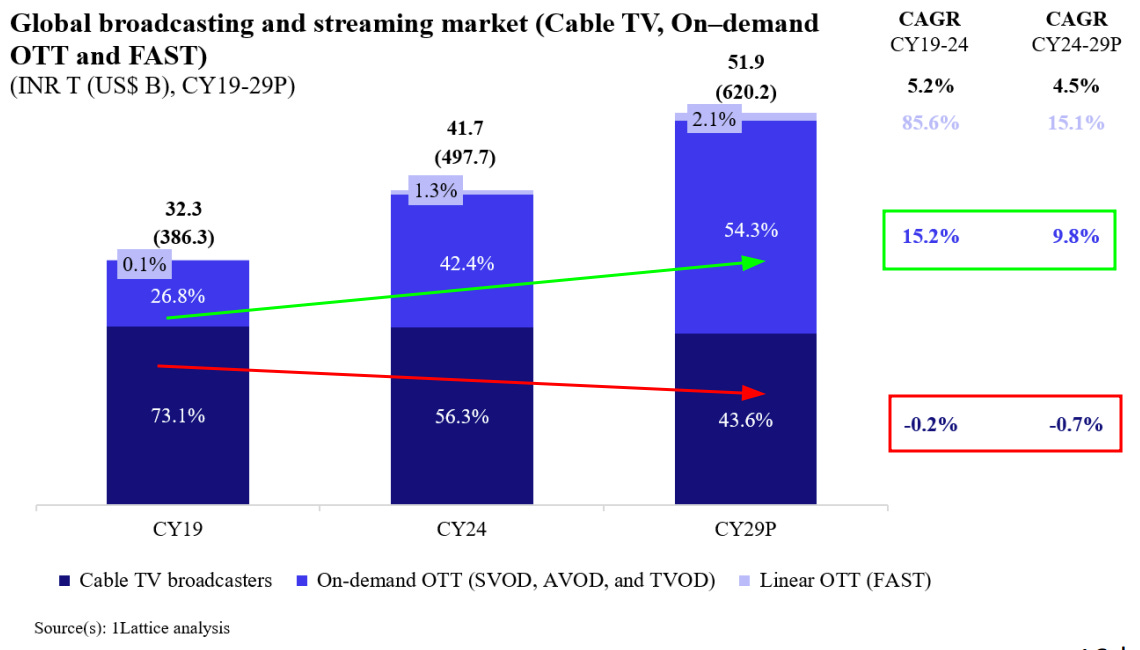

Streaming, you probably know, is eating cable. It hasn’t displaced it yet; In 2024, cable still accounted for over 56% of global viewing revenues. But things are changing quickly. By 2029, cable’s share is projected to fall to ~44%. OTT and free ad-supported streaming (FAST) are taking its place.

As this shift happens, distribution is breaking into a thousand pieces. Back when cable dominated the TV-watching experience, a content owner would only focus on a few distribution pipes. But now, the same piece of content is pushed across a messy sprawl of platforms: FAST apps, smart TV, OTT bundles, and more. This makes operations a nightmare. And that nightmare is an opportunity for Amagi.

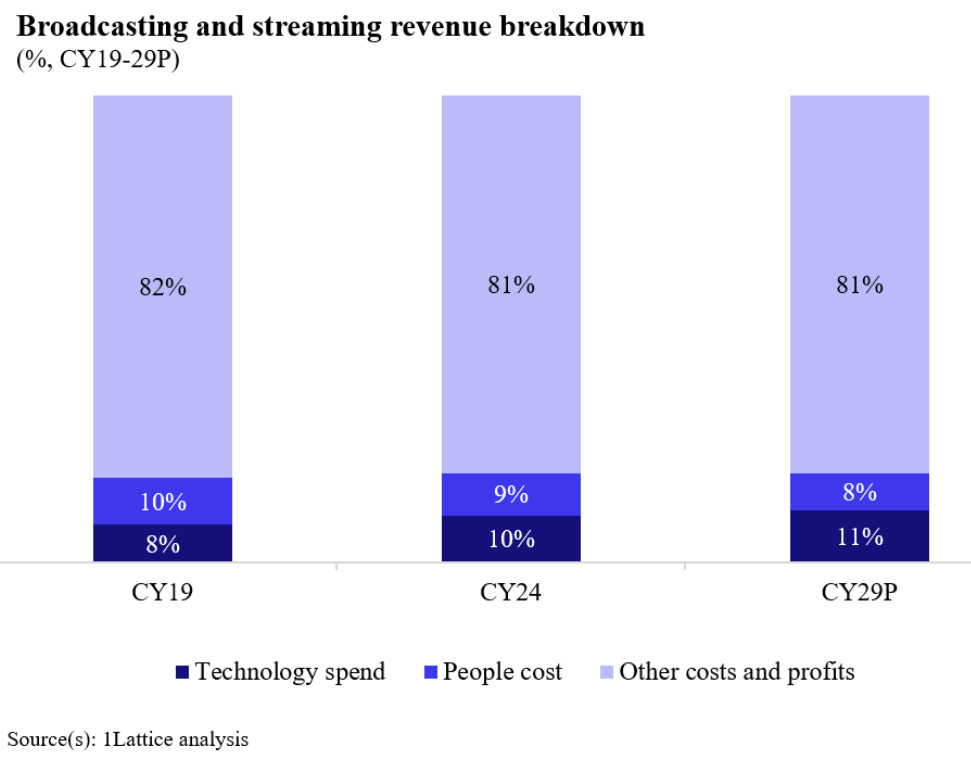

Meanwhile, media companies are slowly being forced into an uncomfortable realization: they have to turn themselves into tech companies. Software, after all, is eating the world. Previously, a TV network would mostly spend on content and marketing, while tech was a small back-office function. That world is gone. Every year, a larger slice of their revenue goes into meeting tech expenses — from ~8% in 2019, to a projected ~11% by 2029. With that, the pool of money available to vendors like Amagi is growing.

Then comes the third force powering this all: cloud migration. Traditional broadcasting ran on heavy, physical infrastructure — which came with big upfront costs. Cloud-based workflows are far more flexible. You can now launch channels faster and scale them up or down, without building a hardware-heavy “broadcast facility”. This is a shift that’s still in its infancy; right now, only about 10% of cable TV networks have moved core workflows to the cloud. But the company thinks that could rise to 40–60% by 2029.

Finally, there’s monetization — with streaming moving en masse to a new business model. After all, people love “free” content. Platforms love ad revenues. “FAST” channels are connecting the two: with streaming channels funded by ads. As FAST grows, so does the volume of ad slots sold on smart TVs. Companies like Amagi benefit twice from this shift: they power more channels, and they get more opportunities to service ad monetization.

The numbers?

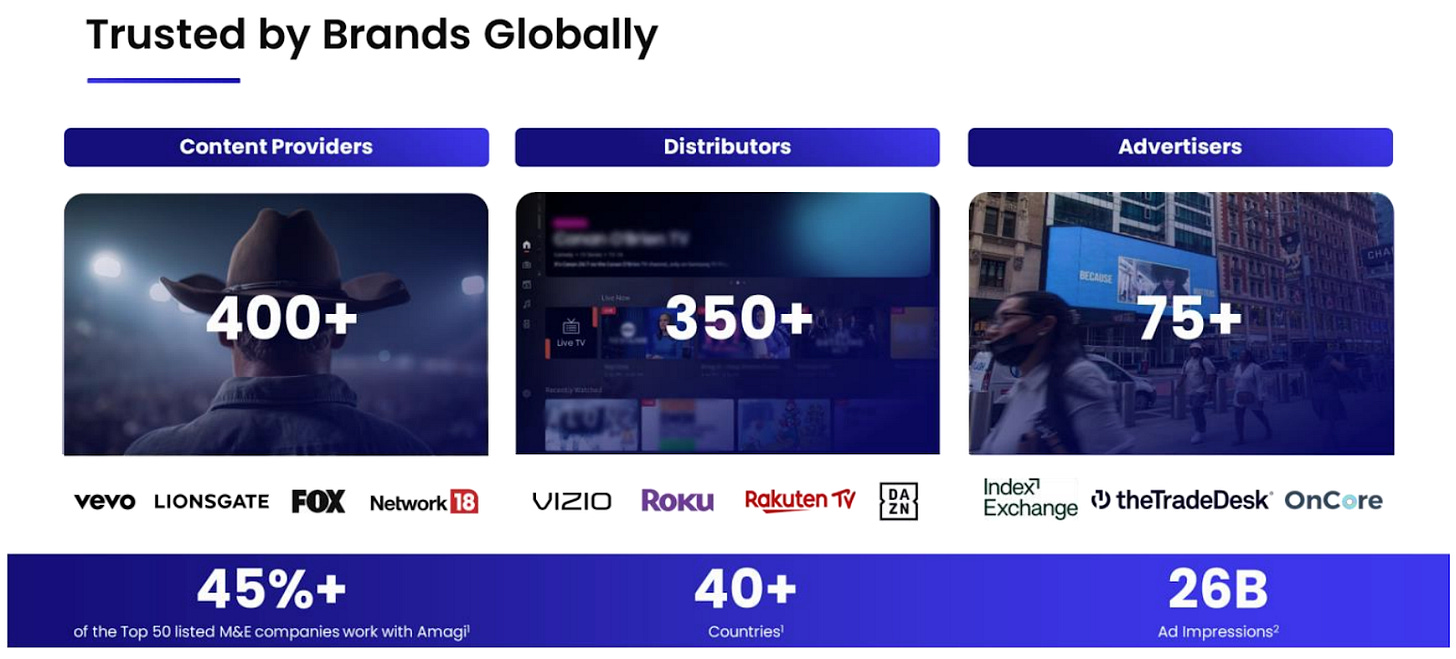

This shift away from cable has been underway for a while, and Amagi’s now operating at scale. As of late 2025, it reported 400+ content providers, 350+ distribution partners, and 75+ advertisers — all plugged into its ecosystem. Most of its clients are outside India. 73% of their customers, in fact, are just from the US.

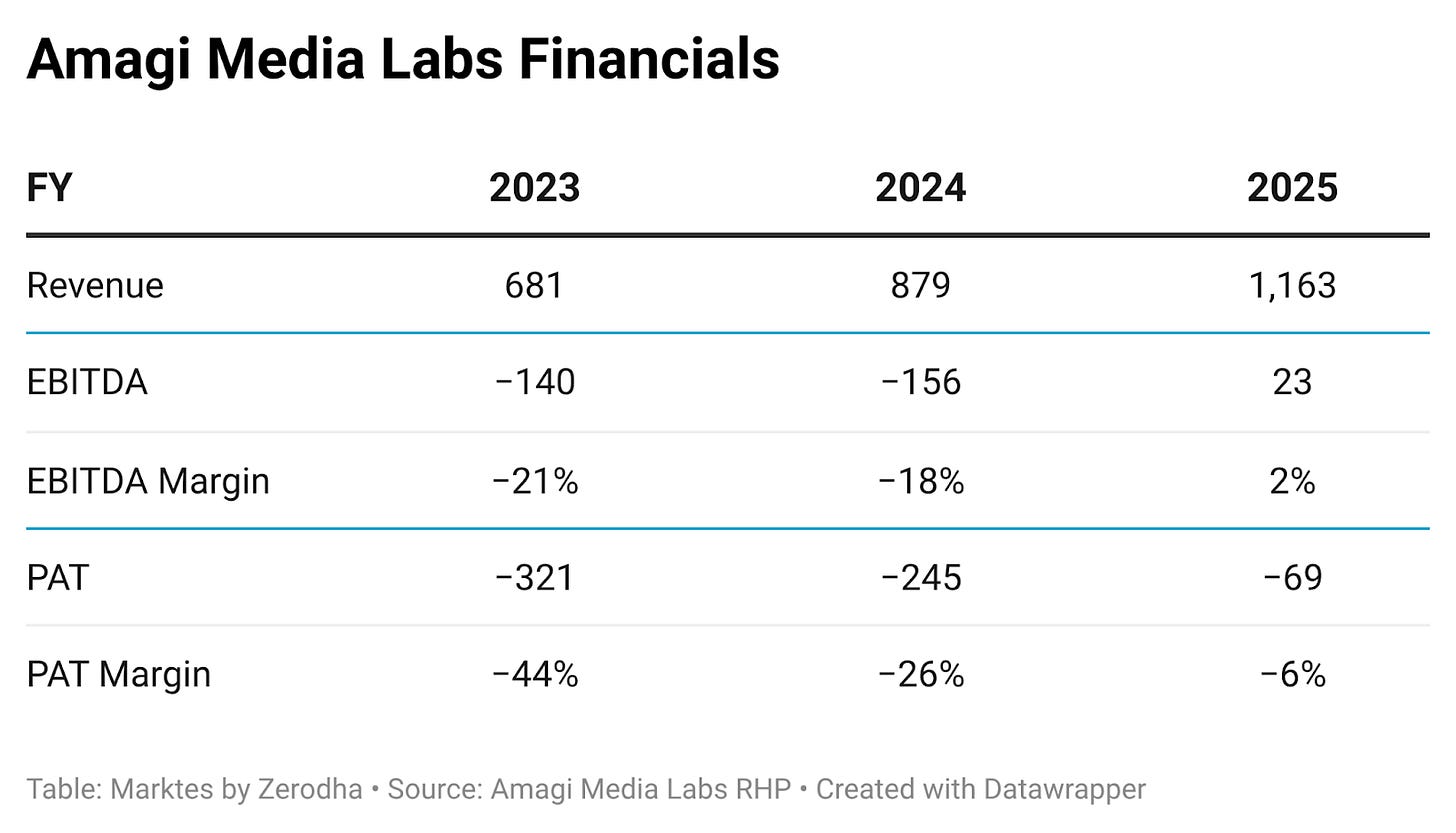

This has all translated into strong, steady growth. In the two years between FY 2023 and 2025, its operating revenue grew at a CAGR of ~30% — almost doubling from ₹680 crore to ₹1,162 crore. In the first half of FY26, it grew even faster, with revenue up ~34.6% year-on-year over the same period last year. All this in today’s rather anaemic media sector.

This money comes from two buckets. In FY25, about 76% of its revenue came from its core cloud software — which helps content owners run and distribute its content, and help distribution platforms manage their channels more efficiently. The remaining ~24% came from its advertising business, where Amagi helps sell ads on these channels. This is a good balance. The ad business is cyclical — ad slowdowns or falling viewership can hit revenues. But with over three-fourths of revenue coming from stable, SaaS-style contracts, Amagi could survive the turbulence.

Another promising sign is how existing customers expand their spending with Amagi. In FY25, the company reported Net Revenue Retention of ~126–127%. That is, customers from the last year spent ~26% more on average, the next year. That is, with time, clients tend to add more channels, features, or monetization services.

The big question, though, is around profitability.

Amagi is loss-making at the PAT level, with negative margins around (-) 5.5%. To be fair, it’s making meagre operating profits — ~2% margins at the EBITDA level. This is a clear improvement from the earlier phase of double-digit losses.

But will the business actually make money?

Amagi has two big cost lines: people and cloud infrastructure.

Employee expenses made up more than half of its total costs, in FY25. But as revenue grows, these costs are making for a decreasing share of their sales — since, in the software business, the same employees can service more customers.

At the same time, the company is struggling to shed its technology and infrastructure expenses. This is, by and large, the rent Amagi pays AWS for its servers. It eats up ~27–29% of their revenue. And it caps their margin upside. In fact, if AWS raises prices, or if Amagi needs more redundancy or bandwidth to meet client demands, those costs could creep up.

In fact, cloud providers could become an existential risk. For instance, AWS already offers media services such as AWS Elemental. In theory, it could bundle these tools with its cloud infrastructure and price aggressively, squeezing independent players like Amagi out of business.

So, the big question is, can Amagi grow fast enough that its revenues dwarf its employee costs?

The hope is that Amagi is entering a “favourable operating leverage” phase: that is, its revenue is scaling faster than headcount and infrastructure. That’s the goal of any maturing SaaS business.

Notably, the IPO proceeds will fund its ongoing operating costs, like cloud and R&D, rather than asset-heavy expansion. That is, new investors are being asked to finance its growth runway — and implicitly, Amagi’s cloud bills. If the company plays its cards well, this influx of money will see it through to the point of sustainable profitability.

That is, if current trends hold. If they don’t, the bull case breaks.

The verdict?

Amagi’s offers an interesting snapshot of how the media and tech landscape is evolving. It has built a big business on the back of industry disruption: as old-school TV gives way to OTT and FAST, it has organised itself around solving the new headaches that emerge.

This is a business with strong tailwinds. Steaming is here to stay, and distribution and monetization are only increasing in complexity. But can Amagi grow fast enough to fend off its high costs? Or will it end up as a platform with structurally low margins?

That’s the thesis worth tracking.

Financing the AI boom, part #2

2 months ago, we covered the nature of the AI bubble through a report by the Center for Public Enterprise. It was a story of US Big Tech aggressively building tons of data centers, all to feed computing power to their own AI systems and that of others. We highlighted the multiple points of fragility that could ultimately crack if the economy is unable to absorb them profitably.

Now, there’s a new paper from the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) which goes deeper into this bubble. While the earlier paper mostly focused on the supply chain, this one focuses on how the supply chain interacts with the capital markets to raise funds. AI is changing not just how we work, but how we’re financing new technologies like itself, and what that means for broader capital markets.

Let’s jump in.

How AI Investment is Being Financed

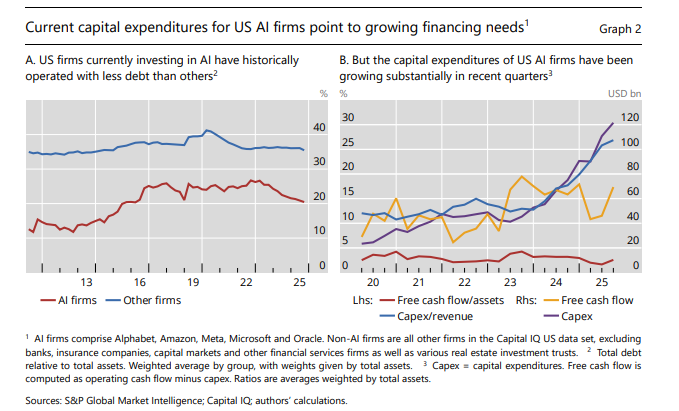

Historically, the big tech firms driving the AI boom — think Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Oracle — have been very profitable and had strong cash flows. So, they’ve always used their internal resources to fund their own growth. They didn’t need much external debt. In fact, the BIS data shows these AI firms have traditionally carried way less debt than other companies in the economy. Their debt-to-asset ratios have been substantially lower than the average firm.

But AI has changed that financing model.

The capex for Big Tech has absolutely exploded, both in absolute dollar terms and as a share of their revenues. In fact, their free cash flow is now lagging behind their capital spending — they can’t fully fund these investments out of their own pockets anymore. The scale is just too massive. We’re talking about building entire data center complexes, each costing hundreds of millions — even billions of dollars. And they need a lot of them, fast.

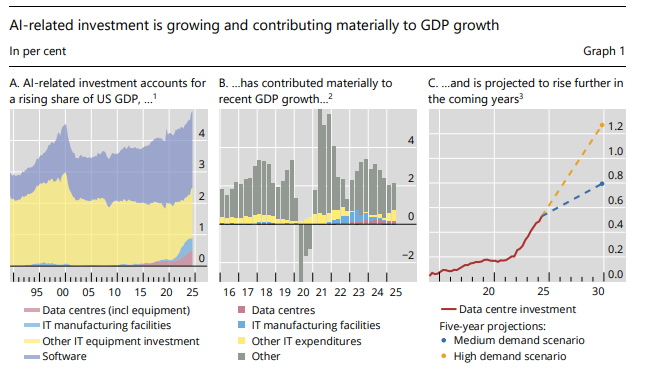

By mid-2025, spending on IT manufacturing facilities and data centers alone hit 1% of US GDP. One percent might not sound like much, but when you add in other IT equipment and software, total IT-related investment reached 5% of GDP. That’s higher than it was at the peak of the dot-com boom in 2000. In fact, total IT investment basically accounted for almost half of US’ economic growth in recent quarters.

Equity financing isn’t always practical, either. That’s because AI valuations can be volatile, and the market windows for raising capital are narrow. Additionally, issuing new stock dilutes existing shareholders, which isn’t ideal when you’re trying to fund long-term, asset-heavy projects.

Instead, Big Tech is turning to the one thing it has rarely been forced to rely on: debt — like corporate bonds, leasing arrangements, and increasingly, loans.

The Rise of Private Credit

And this is where private credit enters the picture. At The Daily Brief, we’ve been meaning to look into the burgeoning private credit space for a while, and this story gives us a chance to take a glimpse.

Private credit mainly refers to loans made outside the traditional banking system. In this system, instead of going to a bank, small and mid-sized companies borrow from specialized investment funds. These deals are negotiated directly between the lender and the borrower, the terms are bespoke, and the loans sit on the fund’s balance sheet until maturity.

Structurally, these private credit funds are closed-end vehicles. They lock in institutional capital for the entire life cycle of their loan portfolios — typically 4-8 years. This is actually important because it means they don’t have the same liquidity and maturity transformation risks that banks have. The sector has exploded from around $100 billion in assets under management in 2010 to over $2.2 trillion today.

Why do AI projects like private credit? One reason is because of what traditional bank financing can’t do that private credit can. Risks in building data centers — like construction delays, power availability issues, tenant concentration — don’t fit neatly into standard bank lending frameworks. Private credit is faster, more flexible, and you can structure deals around these specific challenges. There’s more certainty of execution compared to going through the bond markets.

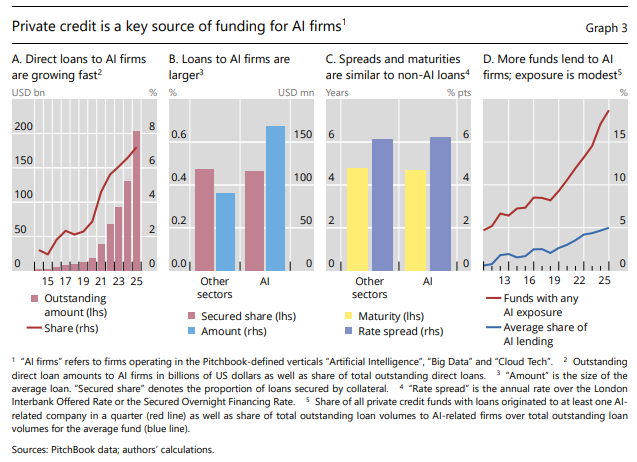

The growth here has been staggering. Outstanding private credit loans to AI-related companies have gone from essentially zero to over $200 billion today. As a share of total private credit volumes, AI-related lending has jumped from less than 1% to nearly 8%. In 2025 alone, these funds originated over $40 billion in new loans to AI companies, compared to ~$3 billion back in 2010.

And just to get a sense of how much bigger this could get: as per its own projections, the BIS estimates outstanding private credit to AI firms to hit somewhere between $300-$600 billion by 2030.

Now, in terms of the standard loan characteristics, private credit loans to AI firms aren’t that different from loans to other sectors. They’re about as likely to be secured by collateral—around 46% versus 48% for non-AI loans. But they are bigger — averaging $169 million compared to $90 million for other sectors. The maturities are similar as well, around 4.7 to 4.8 years. And the interest rate spreads over benchmark rates? Also pretty similar — about 6.2% versus 6.1.

What’s also notable is that about 20% of all private credit funds now invest in AI-related sectors, up from just 5% in 2010. But for the average fund, AI loans still only account for about 5% of their total portfolio. So exposure is growing, but it’s not overwhelming yet.

But what happens when it does get overwhelming?

Financial Stability Risks

The BIS flags a few concerns worth looking into.

First, there’s the leverage issue. These AI companies that used to run lean balance sheets are now taking on more debt. That makes them more vulnerable if things don’t go as planned. If the expected returns on these AI investments don’t materialize, you could see defaults, writedowns, and that could ripple through the financial system.

Second, private credit is less transparent than traditional bank lending. We don’t have the same level of oversight or disclosure. And some of these financing structures might be masking leverage by keeping it off balance sheets. Leverage doesn’t disappear just because it’s out of sight. And then, there’s concerns about the long-term value of the collateral itself. What’s a data center actually worth if the AI boom fizzles?

Third, there’s a disconnect between how the debt markets and equity markets are pricing AI risk itself. Private credit lenders are charging AI firms roughly the same interest rates as they charge other borrowers. That suggests lenders think AI investments are about as risky as the average private credit deal — which is to say quite a bit. But AI stocks are trading at sky-high valuations, which implies investors expect massive future returns and are willing to attach huge risk premiums.

Someone’s wrong here. Either the debt market is underpricing the risk, or the equity market is overestimating the upside. And that gap is concerning, especially as lender exposure keeps growing.

What makes this more complicated is the circular financing within the AI ecosystem that we covered in our previous bubble story. In summary, some AI companies are investing in each other, or in each other’s suppliers, which can create an illusion of demand and inflate valuations. When that unwinds, it could get messy.

How big is too big?

Now, one thing that we touched upon but didn’t fully elaborate in our previous story is how big is the AI boom compared to other technologies.

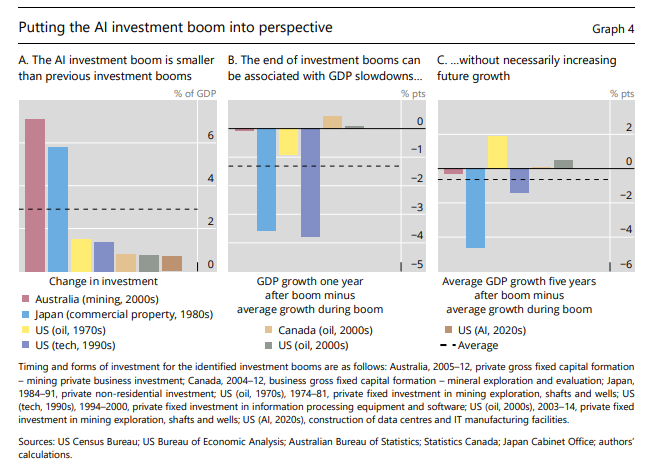

The BIS paper does this comparison as well. At just 1% of GDP, the AI boom is similar in size to the US shale oil boom in the mid-2010s. It’s about half the size of the dot-com investment wave in the late 1990s. However, it’s way smaller than Japan’s commercial property boom in the 1980s, or Australia’s mining boom in the 2010s — both of those were five times larger relative to GDP.

So in historical terms, it’s significant, but not unprecedented, and definitely not yet the biggest investment boom ever.

That said, the consequences of a collapse could still be substantial. When previous investment booms ended, GDP growth typically slowed by more than 1 percentage point. Notably, the biggest contraction came after the dot-com boom, even though that boom was relatively modest in size.

What’s sobering is that there’s little evidence that these investment booms lead to sustained increases in GDP growth over the medium term. Even the dot-com boom, which was driven by genuine technological innovation, didn’t permanently lift growth rates afterward.

If the AI boom were to reverse and companies pull back on spending, you’d likely see a meaningful drag on GDP growth. And if it comes with a stock market correction, which seems plausible given how concentrated valuations are in AI stocks, the spillovers could be even larger.

Wrapping up

So where does this leave us?

The AI investment boom is real. It’s contributing meaningfully to economic growth right now and not just in the US. As we’ve covered in multiple editions, the AI supply chain expands through much of Asia, and even countries that produce copper — an important raw material for data centers. But it’s increasingly being financed with debt rather than cash flows, and private credit—now a $2.2 trillion industry—is playing a central role in that shift.

The sustainability of this boom hinges on whether AI companies can meet the high expectations baked into their valuations. The fact that debt markets are pricing AI risk similarly to other sectors while equity markets are pricing in huge future returns suggests we’re in a period of significant uncertainty. And questions about what happens to the data center collateral if things don’t pan out add another layer of complexity.

Financial stability risks look moderate for now, but they’re growing. And if reality doesn’t live up to the hype, the unwinding could be very painful.

Tidbits

Retail inflation rises for second straight month

India’s retail inflation climbed to 1.33% in December, up from 0.71% in November, mainly due to higher food prices, especially vegetables. Inflation is still well below the RBI’s comfort range, but the uptick reduces room for aggressive rate cuts. Core inflation remains muted.

Source: Economic Times

Apple to use Google’s Gemini models for next-gen AI

Apple and Google have entered a multi-year partnership under which Apple’s next-generation Foundation Models will be based on Google’s Gemini AI and cloud infrastructure. The models will power future Apple Intelligence features, including a more personalised Siri, while Apple says privacy standards will remain unchanged.

Source: X / News from Google

Bloomberg delays Indian bonds’ global index entry

Bloomberg has deferred the inclusion of Indian government bonds in its Global Aggregate Index, citing operational and market-infrastructure gaps. While the review remains open, the delay pushed India’s 10-year bond yield up 5 bps to 6.63%. Long-term inclusion is still seen as likely.

Source: Moneycontrol

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Bhuvan.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

https://open.substack.com/pub/abhinavmishra/p/amagi-ipo-zomato-moment-or-zomato

is AI in a bubble right now? could you write more about the circular financing deals of Big Tech?