India’s Specialty Chemicals Industry Explained

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The special world of specialty chemicals

India’s booming medical implants industry

The special world of specialty chemicals

There are a bunch of sectors we haven’t yet covered on this channel. Forgive us — we’re a small team that’s learning on the go. We’re figuring things out one-at-a-time ourselves, and keying you in on whatever we find.

A sector we’ve been interested in for a long time is chemicals, specifically specialty chemicals. This is a complex space that’s new to us. And so, we’ll keep our scope limited. We’ll pick up three companies, as stand-ins for their respective segments, and dive into their Q4 results. Disclaimer: we’re certain to miss a lot of nuance, and we’ll park a lot of threads for later. But we’ll hopefully come around to it again, one of these days.

But first, let’s start from the very basics.

Specialty chemicals: a bird’s eye view

An industry overview

Most products you’re familiar with — plastics, paints, fertilisers and so on — are made using chemicals. These chemicals come in all forms, from all sorts of sources — from minerals, to plants, to animals. Petrochemicals, though, form the backbone of a lot of chemical products. For example, you get compounds like propylene and benzene from crude oil, which then go on to become building blocks for plastics, detergents, and much more.

The chemicals industry broadly has two segments: bulk chemicals and specialty chemicals.

Bulk chemicals are your standard, mass-produced industrial chemicals. The basic stuff you’d find in your high school chemistry lab — like caustic soda, or sulfuric acid. These are produced in large volumes and trade like commodities, with prices swinging based on global demand and supply.

Specialty chemicals, on the other hand, are a completely different beast. This business is not about volumes, but function; these chemicals are used for very specific purposes. For instance, a specialty chemical might be something that helps a shampoo foam up, or makes a T-shirt wrinkle-free, or helps crops absorb pesticides better. This market is a lot less commodity-like: here, performance matters.

Specialty chemicals have better margins, and are more insulated from commodity price swings. If a customer likes your product, they tend to stick around. But it’s a harder business to get into. You have to work with clients closely — sometimes even co-develop the product with them — and make sure you meet all their performance and safety standards. And if you want to export, you’re also under pressure to meet environmental and safety standards.

So it's harder to get started. But it’s more stable and profitable once you're in compared to a pure bulk chemical company.

Business dynamics

All of that creates a unique business landscape: one which is very fragmented, and very niche.

Unlike other industries, where a few big players dominate, specialty chemicals is made up of many small-to-mid-sized companies, most of whom pick a very specific category to focus on. You might have one company that just makes textile chemicals, another one that only focuses on surfactants for shampoos and soaps, and someone else who is really good at making pigments for paints and plastics.

Very few companies are fully integrated. They rarely do everything from raw material to finished product: instead, most try to occupy one perch in a complex value chain. One might buy basic chemicals and convert them into intermediate ones. Another could take intermediates and formulate the final product. And so on.

So here’s the big takeaway: specialty chemical companies are unique. Each of them has their own dynamics, its own customers, and its own types of R&D. There’s no one-size-fits-all way of looking at this sector.

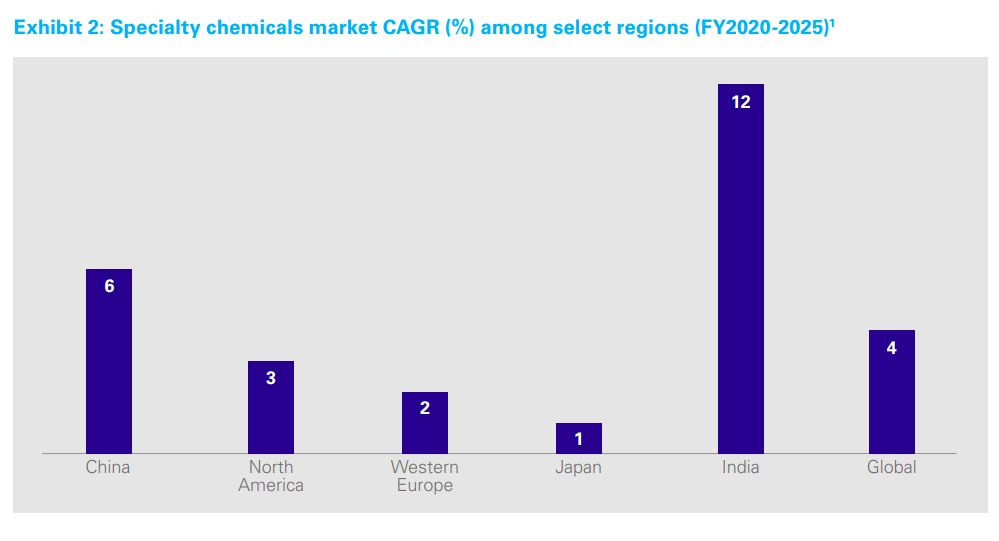

India’s move towards specialty chemicals

For the longest time, we were a bulk chemicals country. Our chemicals businesses ran on large volumes and low cost. But over the last decade or so, things have started shifting.

Over this time, a bunch of Indian companies started focusing on the specialty side. And with that, we slowly started becoming a bigger player in the global specialty chemical export market. For some products — like dyes, pigments, or surfactants — we are already among the world’s top exporters.

This shift was catalysed by China’s exit from the market. A few years ago, China started cracking down on pollution in its chemical factories, shutting many of them down. That made a lot of global buyers look for alternative suppliers — and India stepped up.

Mapping performances

Hopefully, you now have a better picture of the specialty chemicals industry. With that, let’s look at the quarterly results of three companies, from three different specialty chemical subsegments:

Aarti Industries

Fine Organics

Privi Speciality

Aarti Industries

Aarti operates in a very specific niche: it deals in what are called benzene and toluene derivatives. That might sound technical, but in practice, Aarti makes a set of chemical building blocks that it sells to other businesses. Those businesses use them to make things like dyes, pigments, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and fuel additives.

Aarti doesn’t make final products. It doesn’t do everything from scratch either.

Most of its business is about taking basic chemicals, and turning them into “intermediates” — in-between compounds that other companies process further. Many specialty chemicals businesses do the same thing, but Aarti has an edge: it’s integrated across multiple value chains. It takes raw materials like benzene, and turns them into a wide variety of downstream products. Very few players in India have that scope.

Now, before we get into their results, here’s the big picture: as a whole, FY25 wasn’t an easy year for the company. A lot of the end-use industries that Aarti supplies to — like agrochemicals and polymers — have been going through a slowdown. On top of that, prices for many of their products were under pressure globally, especially with China dumping cheaper supplies into the market. While volumes were starting to pick up later on, they weren’t making as much money on each product as before.

Last quarter, their revenue was ₹2,214 crore, up 13% year-on-year. That might sound good on the surface, but the full picture is mixed. Their EBITDA, which measures their core operating profit, actually fell 6% year-on-year to ₹266 crore. Their net profit — or PAT — fell sharply by 27%, to ₹96 crore.

To put it simply, the company sold more, but made less money doing so. Why? Well, their prices are still weak, while costs, especially energy and freight, have grown.

The company actually saw a solid pickup in volumes. Aarti’s non-energy business — basically its core specialty chemicals segment — saw a 14% increase in volumes quarter-on-quarter. That’s a good sign. It means demand is starting to come back after a bad year. Meanwhile, their energy business, which includes things like steam and utilities, saw a 21% volume growth.

But here’s the challenge.

Although Aarti’s moving out more product, it’s not being able to charge the prices it wants. Agro-chemicals, in particular, are soft: there’s too much supply, and nobody has enough pricing power. A big culprit, here, is China’s overcapacity. As Aarti’s management said in their earnings call,

“We are seeing volume recovery for sure, but given the amount of over capacity that exists in China, that incremental volume growth is also served by marginal pricing, and that's where we are not seeing uptick on pricing/margins at this stage.”

Still, not all is bleak. There are a few bright spots.

One of them is MMA — mono-methyl aniline. This product line is used in fuel applications, and they’ve been scaling this aggressively. Volumes are up nearly 40% year-on-year, and they’ve started supplying to newer geographies like the US and Europe. This business is still in the early stages, but it shows Aarti’s ability to absorb shocks, and expand into newer, high-potential categories.

Behind the scenes, Aarti has also been cutting down its costs. They completed a bunch of fixed and variable cost savings projects in FY25 — like installing more efficient turbines for steam, switching to hybrid power sources, and improving yields in key value chains. Nothing flashy, but over time, they’ll help the company protect margins, even if prices stay weak.

Aarti has also been investing heavily in capacity. Their total capex in FY25 was over ₹1,370 crore. And it doesn’t end there; for FY26 they’ve guided another ₹1,000 crore. A large chunk of this is going into what they call “Zone-4” — a new facility with multipurpose plants that will allow them to manufacture more advanced, higher-margin chemicals, especially for pharma and agro sectors. But these projects take time. The bulk of the new unit’s impact will only show from FY27. Until then, Aarti will have to push as much volume as it can from existing assets.

And they’re very focused on doing just that.

For now, their capacity utilization, across major product categories, is still running below peak. For example, their ‘PDA’ chain — used in polymers — has just 33% utilization right now. Even MMA, despite the surge in demand, is at 62%. So there’s a lot of room to grow output without needing new capex. And that’s their aim, this year: driving higher capacity utilization and squeezing more profit out of existing assets.

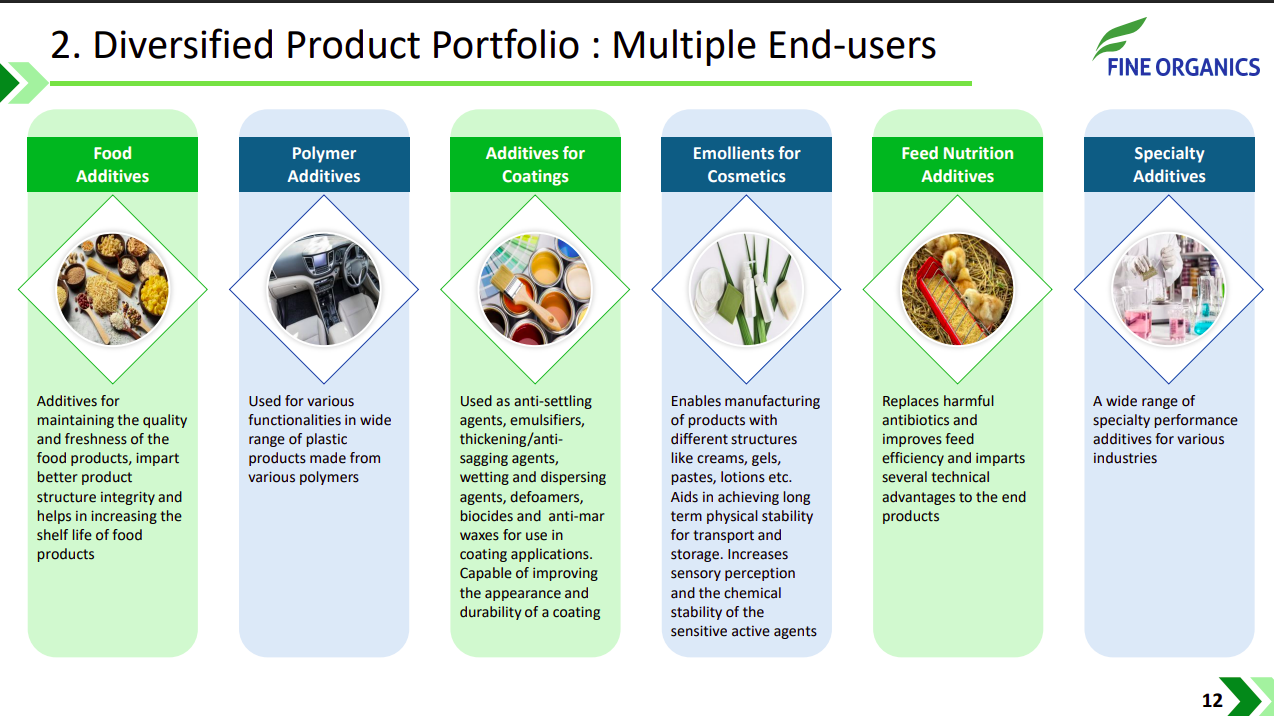

Fine Organics

Fine Organics doesn’t make chemicals in bulk at all. It makes specialty additives — tiny, specialised inputs that go into products like food, plastics, cosmetics, coatings, and animal feed.

These additives aren’t even 1% of the final product’s weight. But they dramatically change its performance. For example, an emulsifier can help cake batter stay fluffy, or a slip additive can make plastic packaging easier to peel. That’s the sort of stuff Fine makes — that last 1% which makes the remaining 99% actually work.

Its strength lies in a niche area called ‘oleochemistry’ — that is, its additives are derived from natural oils and fats. These are marketed as ‘green’ or ‘bio-based’ alternatives to petroleum-based chemicals. That’s the company’s moat: as consumer brands push for more sustainable ingredients — especially in food, personal care, and packaging — Fine's products become more relevant.

In a business like this, everything hinges on relationships. Getting a single product approved by a customer can take 6–12 months. Which is why Fine Organics doesn’t chase a thousand different clients — it picks long-term partners and grows with them.

In FY25, the company ran into a few speed bumps. Like Aarti, Fine’s revenues for Q4 last year grew by 11% year-on-year, reaching ₹607 crore (compared to ₹547 crore a year ago). But this hides its falling profitability: the company’s EBITDA fell by roughly 17% YoY — from ₹144 crore to ₹120 crore. Similarly, its Q4 PAT dropped by ~15% YoY to ₹97 crore, from ₹114 crore last year.

So, once again, we have a company that’s selling more and earning less. What’s going wrong?

The first thing is cost pressure. Midway through FY25, Fine’s raw material — natural oils like palm, sunflower, and castor — started becoming more expensive, and they remained high through the second half. This volatility was outside its control, but it couldn’t pass on those same costs to its customers.

This was a major challenge. Fine had to absorb all the cost inflation for large customers who operate on long-term contracts. It could charge more to smaller or spot customers, but that wasn’t enough to rescue its margins. As CFO Sonali Bhadani explained:

“Wherever there were no long-term contracts, we passed on. But wherever there were, we had to bear that additional cost.”

But there’s a more long-term problem: most of Fine’s plants are already running near full capacity. Its Patalganga plant (referred to as E-73) is the only facility that still has room to grow. That puts a cap on how much its volumes can grow. As its management said:

“All our plants, except E-73, are running almost full. The only growth may come mainly from E-73. Other plants — there will be some small additions here and there, but not much, honestly.”

Basically, in the short term, Fine has little space to grow. This is why it’s preparing a bigger scale-up.Fine has two major projects in motion:

New SEZ facility at JNPA (Navi Mumbai): Early preparation is through — the company has signed a lease, and has environmental clearances in place. Construction shall start soon. This plant will be located in an SEZ, allowing it to primarily serve exports. That will free up existing capacity elsewhere for domestic growth.

Manufacturing plant in the U.S.: Fine already has a customer base in the U.S., but so far has been servicing them by exporting from India. That takes 2–3 months in transit — and limits how much customers can depend on them. A local plant will allow faster deliveries, more business, and stronger relationships.

The management was very clear on this shift:

“Today they are buying from me, but they cannot buy the major share because manufacturing is from India. It takes 2–3 months to reach there. This cannot continue forever.”

The company will start cautiously; after all, this is their first time operating a plant in the U.S., and they anticipate regulatory and cultural challenges. The new facility will begin with the same products Fine already exports. But gradually, it might expand into new products.

Fine has the cash to fund these expansions. They’re sitting on over ₹1,100 crore in cash and have no net debt — even though they’re open to raising debt if needed. The company has also hinted that they’re actively evaluating potential acquisitions, which could add to their capacity even further.

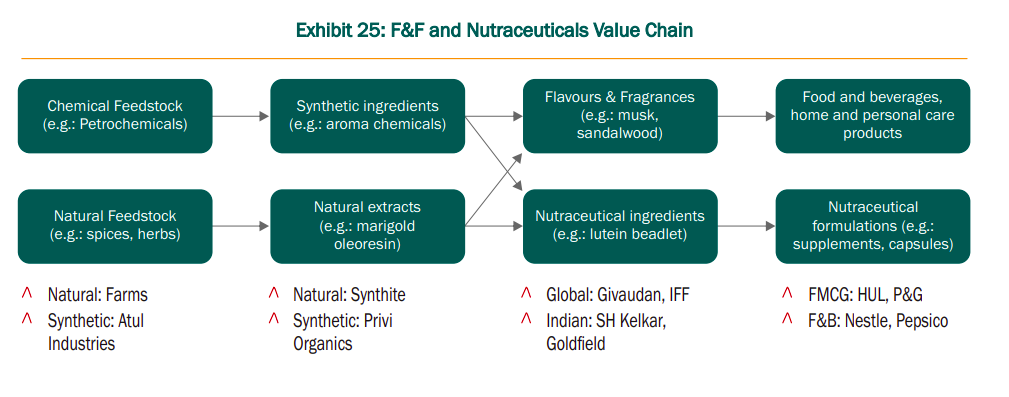

Privi Speciality

Ever bought toiletries for how nice they smell? Well, there’s a good chance the scent comes from a molecule made by Privi Specialty Chemicals. Privi makes scents. Not perfumes, mind you, but the ingredients that go into them — the raw aroma molecules that create that smell. They’re one of the biggest players in India when it comes to making these base aroma chemicals.

Privi makes more than 70 aroma chemicals, including molecules like Galaxmusk, Prionyl, Indomerane, Amber Woody Xtreme, and more recently, newer derivatives that are sold into personal care, home care, fine fragrance, and hygiene products. Their customers include some of the biggest FMCG and fragrance companies in the world — so they’re not chasing bulk; but building sticky, long-term relationships.

Privi has an interesting moat. Most aroma chemicals in the world are made using pine-derived raw materials like CST (crude sulphate turpentine) and GTO (gum turpentine oil). These are usually hard to source in bulk — they come from pulping processes or forest resources, and are hard to churn out at industrial scale. But Privi has spent years securing its access to these inputs.

It has big advantages here. For one, the company is backward integrated — it owns its supply chain. Additionally, it has also built processes to use side-products from its own operations to develop new high-margin products. That’s a little like a kitchen that turns scraps or peels into sauces and garnishes, instead of throwing them away. That’s a big edge. This level of process innovation is rare — and it gives Privi its margins.

And last quarter was its strongest quarter ever. Here’s a snapshot: Privi’s revenue rose to ₹628 crore, up 28% from last year. Its EBITDA grew to ₹147 crore, up 50% year-on-year. Its PAT more than doubled since last year, to ₹64 crore.

This standout performance came on the back of excellent margins. Its EBITDA margin came in at a record 23.5%, and PAT margin rose to over 10%.

What makes these numbers more impressive is what’s behind them.

According to CFO Narayan Iyer, this result wasn’t driven by a one-off spike in prices, or a cost windfall. It was the result of better yields, process innovation, and a healthier product mix. Some “other income” helped, sure, but he was confident that the margin strength is structural:

“It’s not just the other income; it is more with regard to process innovations and yield improvements that we were able to get these margins.”

They’ve also launched new products—Indomerane, Florovane, Amber Woody Xtreme—that are being scaled up and have already been well-received in the market.

Privi’s factories today can make about 48,000 tonnes of aroma chemicals every year. Most of them are already running close to full capacity — at around 85–90%.

To grow further, they’re working on ways to get more output from the same factories, instead of building completely new ones from scratch. They’re improving processes, upgrading equipment, and removing small bottlenecks that slow things down. They think this could increase total capacity to 54,000 tonnes by March 2026 — an addition of about 6,000 tonnes, despite no new facilities. For this, they plan to spend ₹250–300 crore.

They have a very specific vision of what they want to make more of. They’re leaning deeper into high-value, low-volume molecules — products that can sell at prices well above $100/kg. These aren’t made in massive quantities, but can bring in a lot of money per kilo. Many of these are also made using side-products from other processes, so they cost little, and help it run up margins. According to the company:

“From side streams, we make products which give higher contribution… even if the quantity is small, the value is significant.”

This shift is one of the big reasons its margins have steadily improved over the past few years.

The company has also been shedding off its risks. It used to run a huge concentration risk not too long ago: a few years ago, it had just 3 major customers. Today, it works with 6 of the top 10 global fragrance players, and is increasingly getting a larger share of wallet from existing clients.

Here’s one major foray: in February 2025, Privi commissioned ‘PRIGIV’, a joint venture with fragrance giant Givaudan — where it’ll co-develop and manufacture high-end aroma ingredients, that will be sold back to Givaudan under a buyback arrangement. This partnership is still small in scale; in FY25, PRIGIV contributed only about ₹4 crore in revenue. But the company expects it to break even by FY27, and eventually contribute ₹300–₹350 crore in revenue over the next 3–4 years. And because this is an assured business — with volume and margin visibility built in, it could be a solid, predictable anchor for future cash flows.

India’s booming medical implants industry

Speaking of sectors we haven’t covered before.

We just came across a Care Edge report on a market that’s extremely niche — and perhaps a little morbid, to tell you the truth — but no less fascinating for it. This is the market for medical implants.

This is a market that, by the looks of it, is absolutely exploding. Over the last six years, it has grown by a monumental CAGR of 25%. And if Care Edge is to be believed, that momentum isn’t breaking any time soon: from its current size of around $2.5 billion, it’s expected to rise all the way to $4.5–5 billion by FY 2028. In other words, it might double in size in just four years.

And while this isn’t good news — there’s a tragedy on the other side of every sale made in this sector — these numbers still got us to take notice. So here’s everything we thought was interesting from the report.

What are we even talking about

Let’s get more specific. We’re focusing, here, on two things: orthopaedic and cardiac implants.

These are what you put in when parts of one’s body stop working as they should. Orthopaedic medicine deals with your skeletal system — and if that system fails, or breaks (god forbid), you need implants to take over some of the load. These could include joint replacements — knees, hips, shoulders — as well as spinal implants and trauma fixation devices, like rods and screws — something you might be familiar with if you’ve ever had a bad fracture.

Cardiac implants help you with heart issues. These include stents to open clogged arteries, heart valves, and TAVR devices used in valve replacement surgeries.

As you can imagine, this is a market where failure just isn’t an option. These components are mission-critical. If a heart implant fails, for instance, you could literally die. And this is why trust is absolutely crucial, here. Every product has to meet extremely high standards for safety, durability, and performance inside the human body.

And so, this is a market where entry barriers are steep. Manufacturers need precision engineering, cleanroom manufacturing, regulatory approvals, and the ability to conduct extensive clinical trials. On top of that, they need distribution networks, on-ground post-sales support, and, most importantly, the trust of doctors who perform the surgeries.

That trust — and with it, its $70 billion market — has historically rested with foreign multi-national companies. These companies have long dominated the market. Most implants sold in India today are still imported, in fact.

But something is changing. Indian manufacturers are wedging their way into their market — not just at home, but abroad as well. They had cornered business of $2.3–2.5 billion in FY 2024, and are only poised to grow from here.

The explosion of India-made implants

Not too long ago, foreign companies once held a near-total grip on the Indian market for medical implants — in fact, they made up for over 90% of implant sales, at least in value terms, before COVID struck. But in the short years since, things appear to have inverted.

In the four years ending in FY 2024, Indian manufacturers grew their medical implant sales at a scorching 28% CAGR. That’s more than double the 12% clocked by foreign players over the same period.

These players are not just selling in India. They plan to export heavily as well. If anything, exports grew at an even faster rate — at a CAGR of 37%.

What’s powering this surge?

Much of this growth has come from one critical advantage: price. Indian firms make far more affordable products — and that’s helped them capture market share in a segment that’s otherwise known for exorbitant prices. It has brought them a lot of business from government-sponsored insurance schemes, and more generally, from value-conscious markets. Volume growth has followed.

At the same time, in a market like this, price can only push you so far. They’ve gotten here because of how well their products have performed. Domestic players are beginning to meet the same quality benchmarks as their international rivals, which is why they’re finally being taken seriously.

India is also pushing this trend forward with policy support. The government has put out a PLI scheme for medical devices, with an outlay of ₹3,420 crore. Six domestic firms have been cleared under the scheme. For five years, the government will pay these firms 5% of whatever extra they can sell, incentivising them to push harder.

Where do we go from here?

Going ahead, we see different forces tugging at this industry — both from the supply side, and from the demand side.

Demand

Let’s start with demand. There are two reasons you should expect demand to grow:

One, here’s a depressing truth: India’s population is aging fast. According to UN estimates, the number of Indians over the age of 45 is expected to grow at ~2.3–2.4% every year until 2050 — a rate that’s far higher than our overall population growth rate of ~0.6–0.7%. That is, for an ever-larger portion of India, getting a stent, or a hip replacement, will become a real topic of conversation over the next 25 years.

Two, our aging population is also more likely to opt for a medical implant if they need one. Indians are getting richer and more aware of health issues. Health insurance is penetrating deeper, and hospital infrastructure is improving. All of this means Indians who need implants are more likely to get them — another marking of a sustained, long-term boom in demand for implants.

On a less positive note, though, the global market remains a tough nut to crack. While Indian companies have made real progress with exports, there’s much further to go. Globally, they still account for a very small share of implant sales — and that’s mostly because they don’t yet have long clinical track records.

The key challenge, here, is getting into the United States. That’s the biggest market for implants, but also the hardest to access. To get in, you must complete large, US-compliant clinical trials — an expensive, slow, and paperwork-heavy process. And then, you have to beat away entrenched giants that have huge advantages over you — like deep relationships with hospital procurement networks and group purchasing organisations (GPOs), a local presence and strong post-sales support.

This is still an uphill battle for Indian manufacturers. Trump’s tariffs, if they kick in, could complicate things even further. But it’s an interesting space to keep an eye out for. If you see Indian manufacturers manage a toe-hold in the United States, they might be poised to unlock demand at a scale they’ve never seen.

Supply

Supply-side policy choices are doing something interesting to this market.

In 2017, India’s National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA) capped the prices of both stents and joint replacement products. For instance, bare metal stents are capped at ₹10,500. Knee implants fall between ₹32,000 and ₹83,000 depending on the material used. This has caused problems before: many foreign manufacturers were shut out of the Indian market, and withdrew many of their most premium products. Meanwhile, India saw a brief shortage of stents.

But over time, the market has adapted to these price controls. They opened up the market for Indian manufacturers, who were able to nudge their foreign competitors out of business. And this continues to give them a competitive advantage.

The bottomline

The remarkable success of Indian medical implant manufacturers hasn’t gone unnoticed. The road ahead will likely get more competitive. The sector’s already drawing new players — including some of India’s largest pharma companies, like Zydus Lifesciences Limited and Alkem Laboratories Limited. This heated competition could put more pressure on this budding sector. It could compress margins further, especially for commoditised products. And while the government’s support has helped expand this market, if these price caps remain prolonged, they may begin to hurt innovation and R&D spending over time.

Still, this is a segment with strong fundamentals. Demand will only rise. Exports are already blooming. And Indian players are slowly building credibility in a space where trust means everything. For an industry that’s often out of sight, medical implants may just be one of India’s more interesting manufacturing stories in the making.

Tidbits

SEBI Issues ₹2.1 Crore Recovery Notice to Mehul Choksi for Insider Trading Violation

Source: Business Standard

India’s market regulator SEBI has issued a recovery notice of ₹2.1 crore to Mehul Choksi for violating insider trading norms related to Gitanjali Gems Ltd. The notice, dated 15 May 2025, includes a penalty of ₹1.5 crore and accrued interest of ₹60 lakh. SEBI warned that if the amount is not paid within 15 days, it may initiate proceedings to seize Choksi’s assets, freeze his bank accounts, or proceed with arrest. The case dates back to a January 2022 order, where Choksi was found to have shared unpublished price-sensitive information with Rakesh Girdharlal Gajera, who then sold a 5.75% stake in Gitanjali Gems just before fraudulent Letters of Undertaking came to light. Choksi, also an accused in the ₹14,000 crore Punjab National Bank fraud, has been living abroad since 2018. SEBI had earlier issued a separate notice in May 2023 demanding ₹5.35 crore from Choksi for alleged fraudulent trading. Meanwhile, a Mumbai court this month issued a non-bailable warrant against him in a separate ₹55.27 crore bank fraud case involving Bezel Jewellery.

Varun Beverages Acquires 50% Stake in Sri Lanka’s Everest Industrial for $3.75 Million

Source: Business Line

Varun Beverages Ltd (VBL), PepsiCo’s key bottling partner, has announced the acquisition of a 50% stake in Everest Industrial Lanka (Pvt) Ltd for $3.75 million (approximately ₹32 crore). Everest Industrial Lanka is engaged in the production, distribution, and sale of commercial visi-coolers and accessories. The investment was approved by VBL’s investment and borrowing committee, and the deal has also secured clearance from Sri Lanka’s Board of Investment. The transaction is expected to be completed on or before May 30, 2025. According to VBL, the move will help the company internally source visi-coolers within the group, potentially enhancing supply chain efficiency.

Heritage Foods Announces ₹400 Cr Capex as FY25 Profit Jumps 77%

Source: Business Line

Heritage Foods Ltd has announced a capital expenditure of ₹400 crore over the next 18–24 months, including ₹200 crore for a new ice-cream facility and ₹100–150 crore for value-added products and automation. In Q4 FY25, the company reported a revenue of ₹1,048 crore, up from ₹950.56 crore in the same quarter last year, while net profit stood at ₹38 crore compared to ₹40.49 crore in Q4 FY24. For the full financial year, revenue rose to ₹4,134 crore from ₹3,794 crore in the previous year. Net profit for FY25 jumped to ₹188 crore from ₹106 crore, marking a 77% increase. The company said milk procurement prices have stabilized, and consumer price hikes were already implemented in March. It may consider selective price increases depending on products or geographies. CEO Srideep Kesavan stated that business fundamentals remain strong, with consumption showing signs of recovery across channels.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Introducing “What the hell is happening?”

In an era where everything seems to be breaking simultaneously—geopolitics, economics, climate systems, social norms—this new tried to make sense of the present.

"What the hell is happening?" is deliberately messy, more permanent draft than polished product. Each edition examines the collision of mega-trends shaping our world: from the stupidity of trade wars and the weaponization of interdependence, to great power competition and planetary-scale challenges we're barely equipped to comprehend.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Great content on speciality chemicals. Medical equipment story need improvement with more reasearch, insights.

Another company to check out is Vishnu Chemicals. taking lots of backward and forward integration initiatives. what's your opinion?