India's new insurance playbook

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s new insurance playbook

Does central bank independence matter?

India’s new insurance playbook

India just ripped apart its insurance blue-print, changing much of how the industry works.

Last week, the parliament passed the Sabka Bima Sabki Raksha Bill, 2025 — which modifies large parts of the legal regime around insurance. The amendments mark a change in philosophy.

Insurance is an industry that forces you to be circumspect. Since insurance companies sell people protection, were an insurer were to go bust, the consequences could be catastrophic. And so, for years, the government regulated the industry through granular prescriptions. But although this brought stability to the industry, it also created rigidity. Large parts of India simply never received the insurance they needed. Our insurance companies didn’t have the flexibility or the capital to cover everyone.

The new amendments are an attempt to change that. They run into hundreds of provisions, and we can’t possibly cover all of them. But we’ll focus on three broad changes that, in our view, could alter the very structure of the industry.

IRDAI becomes a modern regulator

There are two ways to regulate an industry.

One, you can try to micro-manage things within the law itself. You create extensive, highly detailed legislations that become set in stone as soon as they go through parliament. This tells everyone in the industry exactly what to expect, but if the law hard-codes any gaps or problems, there’s nothing one can do — short of going back to parliament.

The other is what’s called “principles-based regulation”. When you’re drafting a law, you just lay out broad principles and standards that ought to be followed. Then, you trust that your regulator will get the specifics right.

With the new amendments, we’re swinging from the former to the latter.

Earlier, large parts of what an insurance company could do — from how they sold insurance, to how they invested their money, to how corporate arrangements would work — were all spelled out in the law. The specificity was occasionally absurd. For instance, the law specified that if an insurer was refunding someone’s premium, it had to do so by cheque or money order. Anything else would effectively be illegal.

A lot of this, now, has been shifted under the control of India’s insurance regulator, IRDAI.

This doesn’t mean IRDAI has unlimited discretion. The parliament has mandated processes it must follow when it’s making regulations — it has to publish drafts, ask the public for comments, respond to those comments, and carry out periodic reviews of all its regulations. This creates a check on the regulator. If there are major problems in anything it is considering, this gives it ample time to course-correct.

Sometimes, however, all these procedures can get in the way. For instance, a new regulation might be unclear about something, or might need procedural fixes. It might not make sense to go through the entire rule-making process for these minor matters. For such cases, key members of IRDAI’s governing body can release “subsidiary instructions” that clarify things.

In a sense, India’s insurance laws are now “living”. The sector’s no longer married to how the parliament defined things years ago. Instead, the IRDAI has been empowered to change things around, keep what works, and eliminate what doesn’t — without needing a whole new law each time.

The insurance industry will soon look very different

Insurance is a business that trades in money. When you’re offering someone protection from future harms, you’re not just relying on your salesmanship — you’re promising to lock up a part of your balance sheet for them. That takes capital. Without enough capital, India’s insurance needs are immaterial; the industry simply won’t have the firepower to cater to them.

A big goal of these amendments, therefore, is to make it more attractive to bring money into India’s insurance market. This isn’t a matter of simply allowing more investment, but of giving investors much more flexibility over the money they put in. They make the market easier to enter, easier to re-structure in, and easier to exit.

No more FDI caps

Ever since we’ve opened our insurance markets to private companies, we’ve placed strict limits on foreign participation. When we began, foreign investors were only allowed to own 26% of an Indian insurer. That was stepped up slowly over the years, but until these amendments, foreign investments in Indian insurers were still capped at 74%.

Now, that cap has been taken down.

This is a big deal. It doesn’t just allow 24% more investment into our insurance industry — it strips away the friction of investing in the industry. While foreign companies could effectively own Indian insurance businesses before this, getting in was tedious. They had to find an Indian partner to do business with, and form a joint venture. The local partner got a lot of room to negotiate and bargain, simply because they were Indian. As we’ve written before, this could create a lot of friction.

The new amendments make it much cleaner for a foreign company to enter the market. They can simply set up wholly-owned subsidiaries, or buy Indian insurers cleanly.

Restructuring is now easier

The difficulty of entering this business isn’t the only thing keeping foreign capital out. Investors are also wary of what happens after they put their money in — can they manage their stake without getting stuck in paperwork, once inside?

Our insurance laws previously added red-tape around the smallest of ownership changes. If anyone wished to transfer more than 1% of the shares of an insurer, they needed IRDAI’s approval. Fairly routine transactions — stake rebalancing between investors, ESOP-related sales, secondary deals in listed insurers — all of it would be caught in a long, uncertain approval process.

The threshold has now been moved up to 5%. It still restricts large changes in an insurer’s ownership. But it meaningfully reduces the industry’s “compliance tax” on small shifts of capital — giving investors some flexibility around how they acquire a stake, or how they dispose of it.

The amendments also broaden the kinds of group-level restructurings that are legally possible. They now allow schemes where the non-insurance business of a company can be transferred into, or merged with, an insurance business, with IRDAI’s approval. With so many insurance businesses existing within conglomerate structures, this opens some leeway to change around one’s corporate structures.

Easier reinsurance

The amendments don’t just draw in foreign insurers. They also draw in foreign reinsurers, letting them set up branches in India with far lower “net owned funds” — ₹1,000 crore, from the previous ₹5,000 crore threshold. This is, effectively, an 80% reduction in the entry barrier into the business.

Reinsurers play an important role in the insurance industry — they take some of the load of an insurer’s balance sheets. This increases the capacity of the insurance system to insure more risk, and take up larger risks. As more reinsurers enter India’s markets, our primary insurance ecosystem becomes better.

The lower threshold, specifically, opens the door for niche players. The world’s major global reinsurers would probably qualify any threshold. But by lowering this threshold, India could create room for niche reinsurers that are focused on specific classes of risk — like cyber insurance, or aviation insurance.

This might bring more complexity to our insurance market. As new types of reinsurers offer unique services, our insurers might specialise in specific kinds of risk, experimenting with more interesting risk-sharing structures. This could make our insurance markets more mature and complex.

The battle for distribution

One of the great challenges for Indian insurance is figuring out how to actually bring insurance to most Indians. This has been stubbornly hard. Our insurance penetration is stuck at ~3.8% of our GDP — almost half the global average. This figure, in a sense, tells you how much of a country’s economy has been earmarked for long-term protection. Low insurance penetration is a sign of an economy that is under-invested in avoiding risk.

Why is penetration so low? Among other things, Indian insurance has a “last mile problem”. There are large parts of India — especially rural India — that insurers simply can’t reach.

This is, to an extent, the result of broken incentives. So far, a lot of Indian insurance was sold through agents and banks. Both work for commissions. They seek volumes and ticket sizes. For one, this concentrated their business to rich, urban households. Two, they weren’t always concerned with how suitable a policy was for a customer. People were sold policies without a real sense of what they covered, and what they didn’t. Sometimes, they were sold as investments. This left a deep scar on the Indian psyche. Insurance came to evoke mistrust rather than security.

The challenge for law-makers, then, is two-fold: we have to expand distribution, while guarding against mis-selling.

To that end, the new amendments strengthen IRDAI’s control over intermediaries. Our insurance laws, previously, gave IRDAI a lot of power over insurance companies — to inspect or investigate them, issue directions, penalise them for non-compliance, and more. It always had powers over the intermediaries distributing insurance, but this entire toolkit was created with insurers in mind. Now, though, the law extends the full suite of powers to intermediaries as well.

The amendments tighten the legal architecture around intermediaries. It makes it mandatory to get an IRDAI license if you want to distribute insurance — with clear penalties if you don’t. With that, IRDAI gets the right to regulate everything you do. It can decide how you’re permitted to market that insurance, what commissions you can charge, and what compliance requirements you must follow. It has fairly muscular provisions to enforce these requirements too — it can inspect you, search your offices, seize anything it finds suspicious, and penalise you. If it thinks you’ve made money wrongfully, it can even ask you to “disgorge” those excess gains, paying back those you’ve wronged.

In essence, IRDAI has been given a lot of granular controls over how insurance distribution works. Ideally, that gives it the room to calibrate the industry’s incentives — over time, finding a formula for what fair distribution looks like.

Meanwhile, the Act also widens its imagination of what insurance distribution can look like. For the first time, for instance, it explicitly recognises “Managing General Agents”. These are an entirely new sort of distribution creature — they aren’t simply agents; insurers actually give them underwriting authority. MGAs can actually create their own products, price risks, and even manage claims, while the insurer simply brings capital. This lets IRDAI create something new in India’s insurance market: specialist entities that break into new pockets of demand on behalf of an insurer.

This is just one new class of entities. The new amendments give IRDAI the discretion to include all sorts of other entities into the “intermediary” fold.

The bottomline

These amendments signal something that, so often, is missing in India’s legal regime — trust. They’re a bet that the IRDAI is a mature institution that can be trusted to manage the sector, and doesn’t need to be hemmed in with prescriptions. They’re a bet that foreign capital can be trusted to deepen India’s insurance ecosystem, and won’t simply cannibalise the industry.

Will customers respond by trusting the system? Will they come to see insurance as a worthwhile investment in their peace of mind? We’ll soon find out, one way or the other.

Does central bank independence matter?

In late August, Donald Trump did something no American president had done in the Federal Reserve’s 111-year history: he threatened to fire a sitting governor, Lisa Cook, over allegations of fraud.

Those allegations have hardly been proven, and Cook still has her job. In fact, many believe that the allegations were just a pretext for firing her before her tenure ended. The move sent the dollar sliding at the time. People were concerned that if Trump can fire one governor, what stops him from going after Fed Chair Jerome Powell himself?

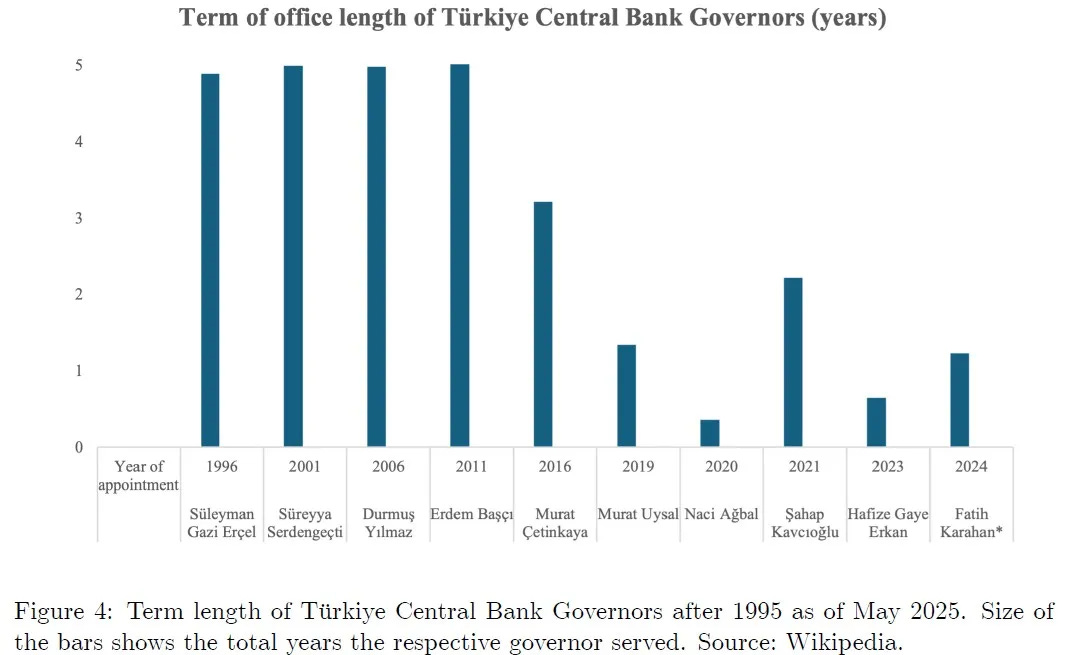

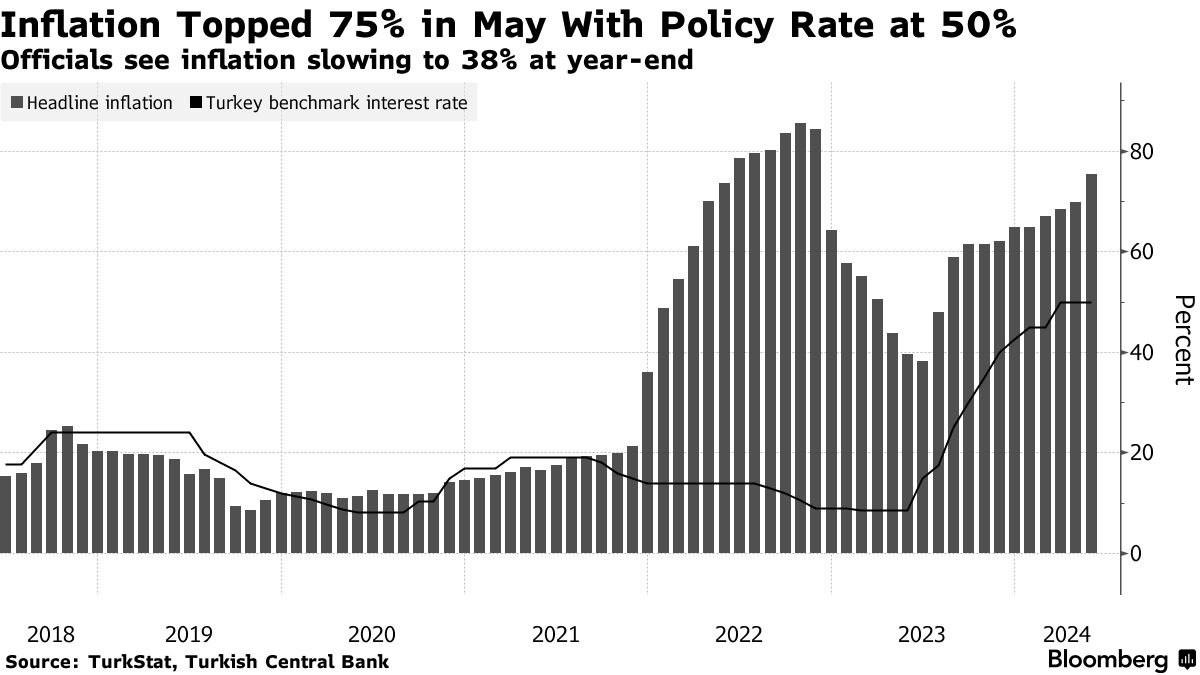

This assault on central bank independence (or CBI) isn’t uniquely American. In Turkey, President Erdoğan spent years forcing out central bank governors who refused to slash interest rates. The European Central Bank launched a controversial bond-buying program in 2022 to cap borrowing costs for indebted member states, blurring the line between monetary policy and fiscal rescue.

India has its own tensions. Over the past decade, India has seen four RBI governors. At the heart of this turnover rate is an unease between the RBI and the government on how to determine India’s economic policy. In fact, ex-deputy governor Viral Acharya warned that governments undermining central bank autonomy would “ignite economic fires“.

The issue of central bank independence matters to how the nation sets its economic trajectory. When they set interest rates, they shape the cost of your home loan, your business borrowing, your savings returns. And when they lose credibility, currencies collapse, inflation spirals, and ordinary people pay the price.

However, there is a debate on how much this independence even matters. What gets achieved by keeping a central bank independent? Is it even possible to have them be truly free of political constraints? These are questions we’ll be diving into in this piece.

The case for independence

Now, at its core, the proponents of CBI don’t say that CBI implied total autonomy — no central bank operates in a vacuum of its own, and its policy is certainly intertwined with government policy. However, what it does mean is protection from the short-term pressures that elected politicians face.

What does this mean? See, governments approaching elections are tempted to “juice“ the economy: cut interest rates, pump money into the system, and boost growth just enough to win votes. But the costs of such policy — like higher inflation and financial instability — come later, usually after the election. And often, these costs negate the nominal growth achieved by governments.

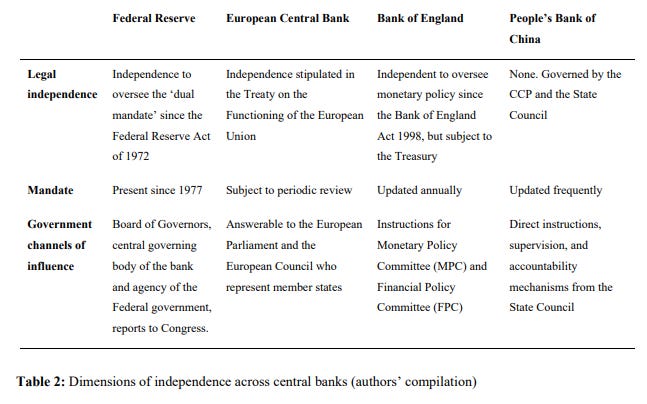

By delegating monetary policy to an independent, technocratic body, countries can resist these pressures. The central bank can raise rates when inflation threatens, even if it’s politically inconvenient. It can refuse to print money to cover the government’s budget deficits. There are various degrees of independence, but broadly, this basic feature must be covered.

But what kind of independence are we talking about, if not a complete one? There are a few elements that proponents of CBI emphasize on.

First, there’s instrument independence: the freedom to choose how to hit your targets. If the government sets an inflation goal of 4%, the central bank decides whether to raise rates, conduct open-market operations, or tighten liquidity, without needing political approval for each move. The government defines the ends; the central bank controls the means.

Second, and perhaps more crucial, is freedom from fiscal dominance. This means the central bank isn’t obligated to finance the government’s deficits. If the treasury is running out of money, the central bank shouldn’t be forced to print more of it, or to keep interest rates artificially low so that the government can always borrow cheaply. When fiscal considerations dominate monetary policy, the argument goes, the result is often higher inflation and eroded credibility.

Turkey offers the starkest warning. When president Erdoğan demanded rate cuts against all logic, investors fled and their currency, the lira collapsed. Ordinary Turks faced a cost-of-living crisis as prices nearly doubled in a year. The central bank’s loss of independence didn’t boost net growth at all.

The case against independence

On the other hand are those who argue against CBI.

One of their key arguments rests on a simple, but provocative idea: that monetary policy alone is too narrow to deal with the full range of economic problems. Central banks can raise or lower interest rates. But they can’t create jobs, build infrastructure, or steer investment toward productive sectors. Before 2008, many central banks kept inflation perfectly stable while completely missing the buildup of financial risk that triggered the global crisis. Their mandate was narrow, so their vision was narrow too.

This narrowness inherent in CBI, the argument goes, also embeds certain biases into policy-making. When inflation rises, central banks raise rates, which means that firms borrow less and stop expanding. That, in turn, means that firms stop hiring more, and may even fire people. Additionally, if workers only expect prices to rise, then they will demand for higher wages. But with unemployment, their bargaining power to make such demands falls.

In sum, the attack on CBI is that at the end of the day, wages bear the brunt of inflation-targeting policies of a central bank. By design, they prioritise price stability over full employment or higher wages.

Now, this wouldn’t be a big problem if inflation rose because there’s too much demand in the economy. However, if the inflation occurs due to extraordinarily high profits of companies, for instance, then monetary policy will fail to get it right, and pass on the costs of inflation to ordinary people instead of firms that can absorb it.

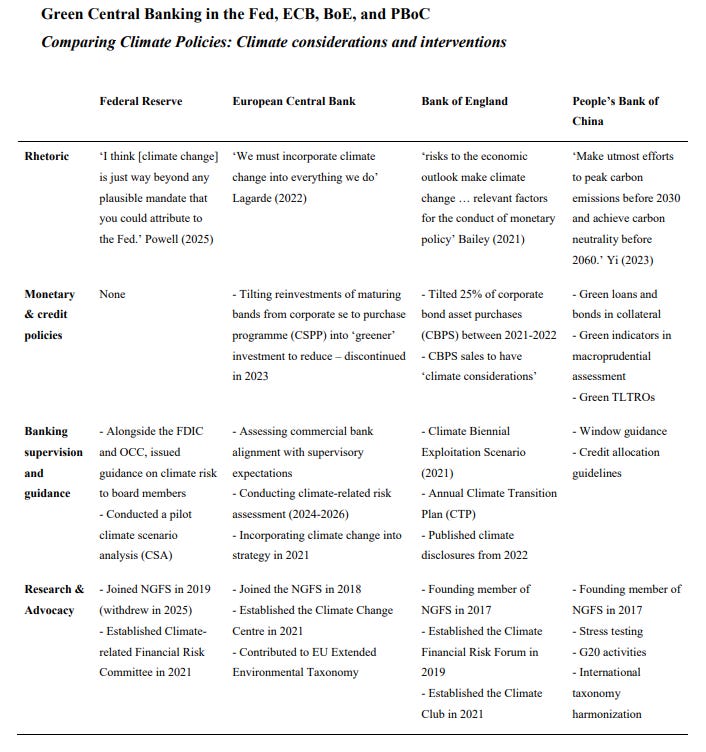

However, beyond this flawed design, there’s a second, more structural critique — that when monetary policy is combined with fiscal policy, it can be more effective in achieving certain goals. And one case critics often use to make their argument stronger is China. China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) does not operate independently of the government. Yet, China’s economic management has been remarkably effective: decades of high growth with moderate inflation.

More strikingly, as argued by economists Mathias Larsen and James Jackson, this arrangement helps China move faster banks on the green transition. The Chinese government, through its stronghold on China’s public and central banks, directs cheap, low-interest rate credit toward green industries as part of its broader strategy. This coordination of monetary policy with government policy is, in part, what has helped them achieve success in green technologies.

Yet, at the same time, Larsen and Jackson also highlight that the success of this model doesn’t mean it can be replicated elsewhere — and certainly not without risks. This type of coordination can indeed create financial instability by hiding or delaying costs. Operational independence, Larsen and Jackson say, may have some merit when it comes to keeping inflation at bay when there’s excess demand in the economy.

In fact, despite their differences, both sides of the CBI debate agree on many things. For one, they agree that unfortunately, wages often bear the brunt of these policies. They also agree on principle that central bank independence isn’t — and shouldn’t be — absolute.

Where the differences lie is mostly in their outlook. For instance, PIIE argues that central banks often purchase their own government’s securities in order to ensure markets work smoothly. But this complicates the long-term pursuit of low inflation by entangling monetary policy with fiscal outcomes, and weakening the credibility of future tightening. As a result, central banks are often left relying on blunt policy tools. Critics of CBI counter that this reliance is not inevitable, and that central banks still have choices over who ultimately bears the costs of policy adjustment.

They argue for solutions accordingly. The pro-CBI side believes that to solve this, central banks must be given more autonomy to say “no” to the government’s fiscal demands if it deems them unfit. The critics, however, argue that in today’s day and age, independence often acts as a barrier to achieve certain economic goals. If anything, during economic crises, monetary policy and fiscal policy often go hand-in-hand.

Where India fits

India’s experience sits somewhere between these camps — drawing lessons from both, while also illustrating the limits of both.

On paper, the RBI has moved significantly toward independence. The Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act forbids the RBI from directly buying government bonds in the primary market. The 2016 inflation-targeting framework established a Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) with a clear mandate: keep inflation at 4%, plus or minus 2%.

But de facto independence is another matter. In fact, ex-Deputy Governor Viral Acharya has said that in India, fiscal policy dominates over everything. In his time at the RBI, Acharya argues, the government’s persistent fiscal deficits prevented the RBI from achieving their long-term inflation targets. The RBI adapts, but often reluctantly, at the cost of their ability to deliver low inflation.

Additionally, Acharya argues, the RBI cannot enforce the same discipline on India’s massive state-owned banks that it can on private ones. It lacks the power to replace management or revoke licenses without government approval. However, state-owned banks consistently run losses, and are recapitalized by government borrowing. This adds to the problem of fiscal dominance that Acharya talks about. All of this led to a huge fallout between then-RBI governor Urjit Patel and the government.

And yet, India has also demonstrated the limits of strict insulation. During COVID, the RBI implicitly financed the government’s massive stimulus by buying bonds in secondary markets and keeping yields low. This was coordination, not independence, and it was necessary.

Another instance of coordination between the RBI and the government is in 2013, when the US Fed announced a slow rollback of bond purchases. We won’t go into the complex dynamics of the crisis here, but in this case, the coordination was in reverse. The government actually cut back on fiscal spending, while the RBI raised rates.

So India lands somewhere in the middle of the CBI spectrum, perhaps uniquely so. The formal architecture of independence exists, and it has delivered real gains in credibility and inflation control. But the pressures of fiscal needs and public bank finances mean that the RBI often operates with one hand tied.

Conclusion

The debate over central bank independence isn’t about whether governments should meddle in monetary policy or not. As it is, monetary and fiscal policies are often strongly intertwined. The debate is really about what institutional and political arrangements lead to desirable outcomes for the whole economy.

When central banks are insulated too well, goals like full employment, wage growth, climate action often get sidelined. When they’re not insulated enough, what we lose is price stability, credibility, and the confidence of the markets.

There’s no perfect answer. Only trade-offs, and the wisdom to navigate them.

Tidbits

The PM E-DRIVE scheme delivered 1.13 million electric vehicles in its first year—3.4 times higher than FAME II’s annual volumes—despite halving per-unit subsidies to ₹5,000 per kWh, signalling a maturing EV market.

Source: BSHCLTech will acquire Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s telco solutions business for up to $160 million (~₹1,440 crore). The deal includes nearly 1,500 engineering specialists and follows HCLTech’s $225 million HPE asset purchase last December.

Source: ETThe Finance Ministry confirmed there is no proposal to restore the Old Pension Scheme for central government employees. Over 1.22 lakh employees have opted for the Unified Pension System, which offers a guaranteed minimum pension of ₹10,000 per month.

Source: ET

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Manie.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Great points as always!

Recently wrote something on how the insurance penetration in India has another issue on the adoption side driven by working capital

https://substack.com/@aryanmulchandani/note/c-182609652?utm_source=notes-share-action&r=10pwyd