India’s new electricity policy tries to switch lanes

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s new electricity policy tries to switch lanes

The contradictions of India’s efforts to digitalize

India’s new electricity policy tries to switch lanes

A lot is happening on the regulation of Indian power.

Earlier this month, the government released the Draft National Electricity Policy (NEP) 2026, a massive update to India’s electricity blueprint since the NEP of 2021. Just before that, in December, the Draft Electricity Amendment Bill 2025 was in circulation, aiming to repair the broken state of India’s state discoms — which we covered previously on The Daily Brief.

Something is afoot. India wants to become a manufacturing powerhouse, but our industrial electricity tariffs have always been relatively too high. This is partly because of the choices we made as a country — about who we would subsidise and who would bear the bill — but partly, it is structural. Our power procurement has always been rigid, making Indian discoms financially inefficient. Meanwhile, most of our transmission planning prioritised inter-state corridors, while grids within states were neglected.

The old model is broken. The Draft NEP 2026 acknowledges that. But there are also new opportunities — renewables like solar and wind could help usher in a new paradigm. In this episode, we’ll be looking at how the 2026 NEP is trying to mid-wife this change. This is a strategy document; not a legal one. But it indicates the directions that our energy laws might take.

Let’s dive in.

Power procurement

If you want to understand where Indian discoms bleed money, start with how they procure power.

As we have explained before, power procurement makes for ~70% of a discom’s total costs. For decades, discoms have been locked into long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) — 20-25 year contracts with fixed capacity charges. The discom would pay for this whether it used the power or not.

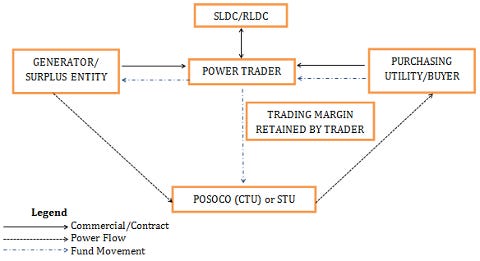

India has acknowledged this as a problem before. The 2021 NEP wanted to move at least 25% of all power procurement away from inflexible PPAs to spot markets by FY 2024. However, that vision didn’t become reality. Only 13% of power gets transacted in spot markets even today.

Why didn’t it work? Well, for one, discoms didn’t see their PPA costs change even if they procured power on the spot. But secondly, discoms didn’t trust markets a lot. Spot prices for power were far more volatile than what the PPA assured. And voters wouldn’t take kindly to increases in power prices. Without a major institutional change, there was little reason for discoms to embrace electricity markets.

Renewables have changed that. We’re deploying solar power faster than coal. And the abundance of power offered by renewables often makes market procurement cheaper than coal-based PPAs.

At the same time, market procurement, alone, is a bad strategy. The pricing of renewables swings wildly, depending on the time of day and weather conditions.

So, the Draft NEP 2026 tries to split the difference. It gives discoms flexibility — it doesn’t mandate any numerical targets. But it brings in new instruments that could help transition towards more market-oriented schemes.

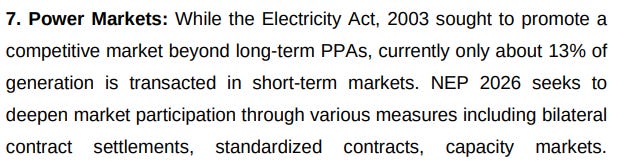

One such instrument is the Virtual Power Purchase Agreement (VPPA). Unlike a traditional PPA, where a discom physically procures electricity from a coal plant, a VPPA entails no such direct supply. It’s a hedging instrument between the final consumer of power and a renewable energy generator (REG).

Here’s how it works. A buyer and the REG agree on a strike price of power. Then, business goes on as usual: the REG sells energy to the grid at market prices, while the buyer gets power from its local discom. But every month, a power exchange settles the difference between the market price and the strike price. If the former is higher, the generator pays the buyer the difference, and vice versa. This can help raise the share of renewables in India’s energy mix, while reducing the burden of procurement on discoms and old coal plants alone.

The Draft Electricity Amendment Bill complements this with stricter financial discipline for discoms. For one, it mandates that discoms can’t hide losses in “regulatory assets” that are passed to future consumers. It also gradually phases out cross-subsidies for manufacturers and the railways, which have their own captive power systems. And finally, it allows private players to compete with discoms.

We’ve gone into most of this, in detail, in our episode on discoms. Check that out for more details.

Grid modernization

However, instruments can only go so far. These changes won’t be enough unless India’s power grid itself is modernised. That is what the new NEP tackles next.

Changing institutions

Let’s start with the current structure of the grid.

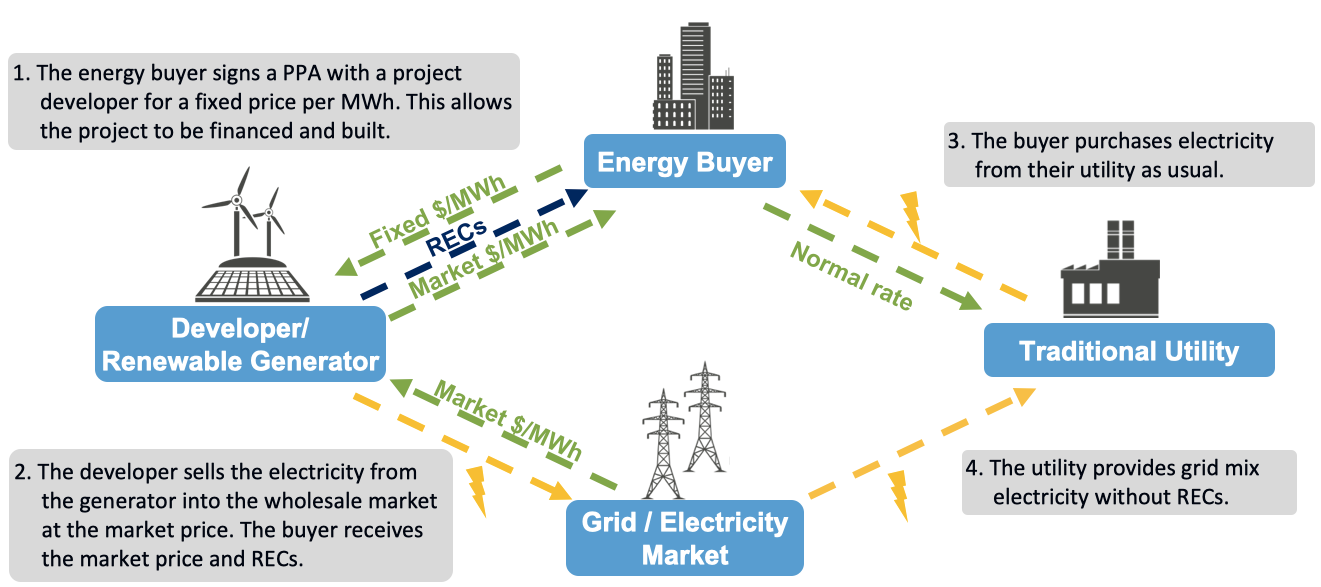

The grid in any state is governed by two key entities: the State Transmission Utility (STU), which builds out intra-state transmission lines, decides voltage levels, sets technical standards, and so on, and the State Load Dispatch Centre (SLDC), which oversees day-to-day operations.

In practice, though, in most states, both functions are performed by the same entity.

This creates an incentive mismatch: the entity that decides where and how power flows also owns the grid. And so, it could try to compensate for failures in one by over-doing the other.

Imagine, for instance, that a state’s power system faces persistent congestion. There’s a way to run the grid so that it doesn’t happen — better forecasting and scheduling, tighter congestion management, smarter grid tech, and so on. But this is hard to pull off. There’s also an easy answer, but a bad one: over-build the grid.

The latter is wasteful, but sadly, it is also attractive. Utilities returns are regulated — they’re given a fixed rate of return on each project’s cost, whether or not it needs to be made.

This detracts the entity from choosing sophisticated solutions. It’s just easier to reduce day-to-day stress by locking in “firm” supply through long-term PPAs, often with coal plants. They’re an operational short-cut; they’re predictable, and don’t have to be managed constantly. Of course, they load the system with fixed obligations that run for decades, crowding out cleaner, more flexible options. But that is somebody else’s problem.

This is the very dynamic the NEP is trying to move away from.

Earlier, India had recommended that states separate both these functions. But back then, they were set in their ways. Separation was hard to achieve, and as long as it wasn’t mandatory, nobody wanted to make a move.

The latest NEP explicitly mentions that state governments should establish an independent company for day-to-day management. This could become an unbiased grid referee. Without the option of expanding the grid, the SLDC will have to make efficient grid operation its priority. This will also increase trust in SLDCs — buyers and generators can expect the dispatch to behave in a way that doesn’t undermine their VPPAs.

Competitive bidding

To complement this SLDC-STU split, the new NEP has made tariff-based competitive bidding (TBCB) the default mode for allocating all grid projects. In essence, private players will be allowed to bid against public entities for projects, with the lowest bid winning.

This wasn’t compulsory under the earlier version of the NEP. Previously, competitive bidding was allowed, but tariffs could also be set using the “cost-plus” method — where you would be compensated for the costs you took on, rather than your performance or market demand. Naturally, utilities mostly chose this. This pushed the system towards larger, more expensive plants. If your returns were linked to the capital you put in upfront, you would want to build the most expensive possible project that could get approved.

This could fix the mis-match: pushing entities to try and set up the most efficient possible projects.

Inter-state vs intra-state

Third, the NEP prioritizes building intra-state lines far more than inter-state lines.

For years, India’s grid planning focused on inter-state corridors — big electrical highways that move power from coal-rich states (like Chhattisgarh) to demand centers (like Maharashtra).

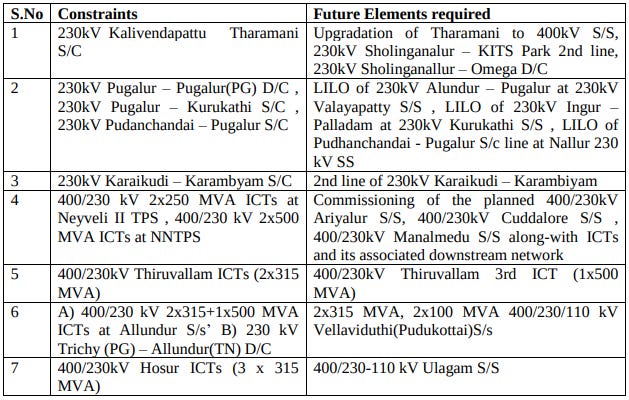

This made sense when large, centralized coal plants were the primary source of power. But as renewable generation has grown, the congestion has moved inward. Solar farms and wind installations are more decentralized, and closer to load centers. But without enough infrastructure, this also creates bottlenecks. Our poorly optimised local grid can’t handle the variability that comes with renewables. And so, increasingly, the worst bottlenecks increasingly occur within states.

Take Tamil Nadu, for instance. During surplus periods, it actively sells power to neighbors Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, which need it more. On aggregate, the state is often able to balance supply and demand through inter-state trade. However, its own lines between renewable-heavy areas (like Tirunelveli) and industrial hubs like Chennai aren’t well-developed. So, power imbalances within the state are common.

Renewables take charge?

The big shift this NEP signals is a move towards renewables.

The 2021 NEP saw coal as the backbone of the system. It was still the cheapest source of energy. Renewables, then, were merely a useful supplement.

While the new draft continues to keep coal front-and-center, it is no longer always the cheapest energy source. In fact, we have excess coal capacity — many coal plants are stranded assets which could turn into bad loans for banks.

And so, there’s no longer a heavy focus on creating new coal capacity. Instead, the goal is to utilize the existing coal fleet better, ramping it up and down quickly to complement variable solar and wind generation. It is, in other words, just a stepping stone for the transition towards a renewable-heavy economy.

This shift is backed by new enforcement mechanisms. State regulators must enforce targets that specify how much of a consumer’s power must come from non-fossil sources. Now, these targets existed before, but they were toothless. There were no penalties for not meeting them. But the recent Electricity Amendment Bill changed that.

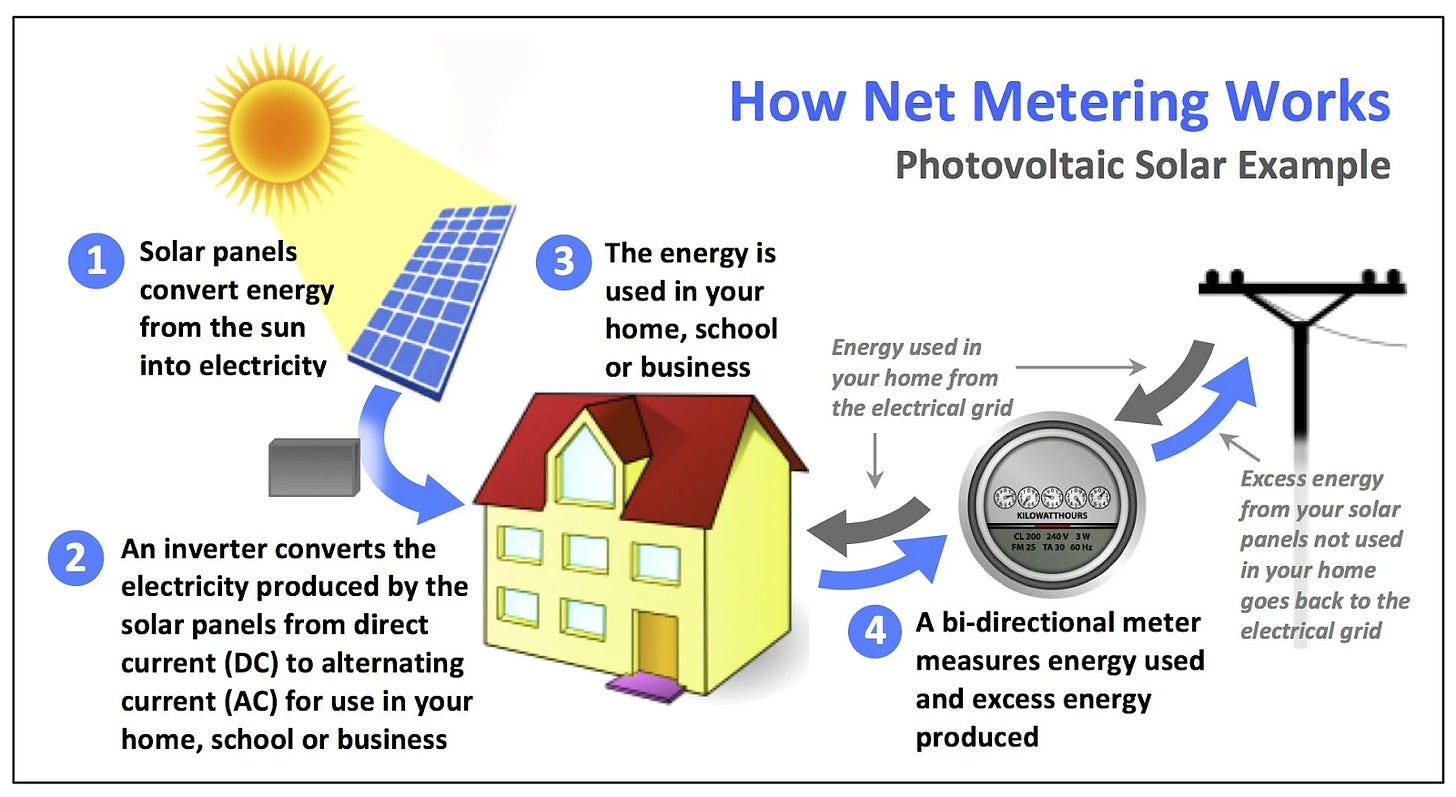

The policy is also betting heavily on decentralized energy generation. It promotes rooftop solar coupled with energy storage, aiming to turn consumers into “prosumers“ who both consume and produce power. But there’s a catch: consumers with installations over 5 kW of capacity can’t avail net metering. This means that your power bill won’t be calculated net of how much power you’ve supplied to the grid — you must settle your exports separately.

Why would a pro-renewables policy discourage net metering? That’s because net metering would let “prosumers” use the grid as free storage and reduce their power bills to near-zero. They would export surplus solar during the day and draw power at night, without paying for the grid infrastructure that makes this possible. The policy wants “prosumers” to invest in their own storage instead.

Conclusion

There are many things in the new draft of the NEP that we couldn’t cover. They include a focus on nuclear, hydropower, battery storage systems, and so on.

However, at a broad level, the NEP reflects India’s ambitions to shift from a non-market, centralized power system, to a renewable-heavy, market-oriented grid. The seeds of this shift were laid in NEP 2021 itself. But plenty has changed in the last 5 years, and the latest NEP is doubling down on those ideas.

The execution of the NEP will not be easy, however, and depends mostly on the incentive structure of various participants. The existing incentives have created inefficiencies that do not seem to fit a grid focused primarily on renewables. Success will depend on whether the energy laws inspired by the policy are able to shape those incentives for the better.

The contradictions of India’s efforts to digitalize

India wants to be a manufacturing powerhouse. The 2014 Make in India campaign set an ambitious target: manufacturing should contribute 25% of GDP by 2022. That didn’t happen — the sector managed just 13% that year; around as much as it did a decade ago. Meanwhile, services keep growing, now accounting for over half the economy.

This isn’t a new story. India’s growth trajectory has been services-led for decades, a pattern economists often consider unusual for a developing country. Most countries in the world have gone from agriculture, to manufacturing, to services. Somehow, India seems to have skipped some steps in between.

Do India’s own policy choices inadvertently reinforce this pattern? A recent paper by researcher Yutong Chen suggests they might. Chen tries to look into whether all firms can universally take advantage of a massive digitalization push, taking India’s recent efforts as the subject of her study.

The results reveal interesting nuances about the nature of India’s growth so far, and what it might mean for our latest push to build factories and create industrial jobs. Let’s dive in.

The natural experiment

To find the answers, the paper situates itself at a crucial point of time in India’s economy.

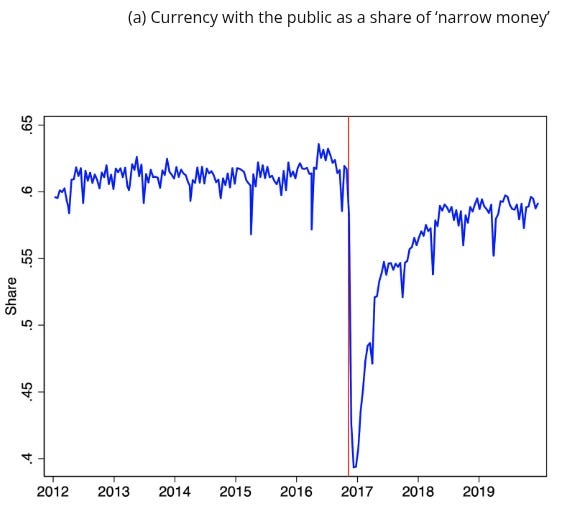

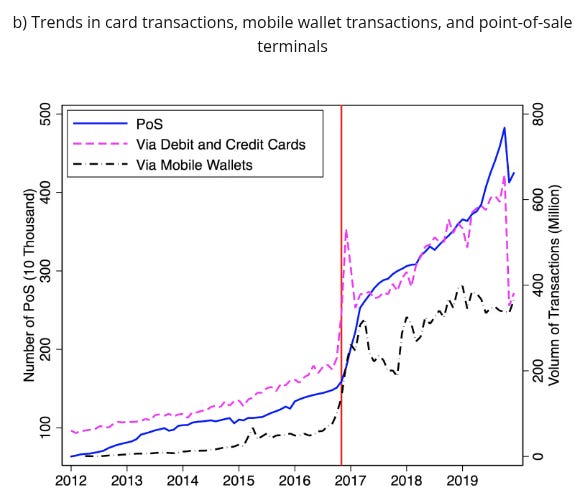

On November 8, 2016, India announced that all old ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes—86% of currency in circulation—would become invalid going forward. This was meant, supposedly, to fight corruption and tax evasion. But, the immediate effect was a massive cash crunch that lasted months, devastating many small businesses.

As a silver lining, demonetization kickstarted the eventual explosion of digital payments in India. UPI adoption surged manifold, debit and credit card transactions grew, and mobile wallets like PayTM saw exponential growth. India’s economy was going through a digital drive like no other.

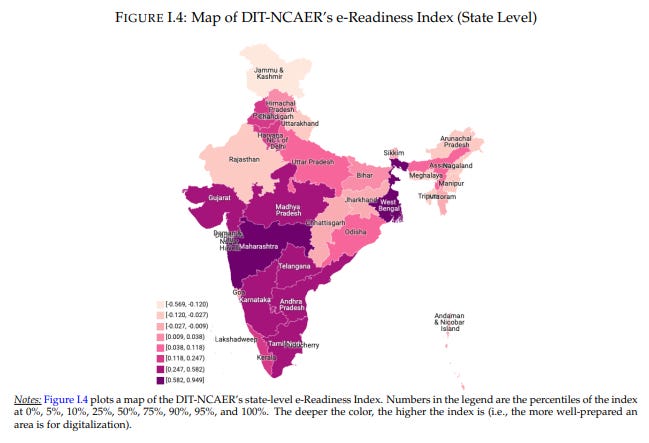

Chen saw an opportunity here. The demonetization shock hit the whole country at once, but the ability to adapt to it wasn’t uniform. Some areas had better digital infrastructure: more stable internet, more data centers, higher mobile penetration, and so on. Others didn’t.

This created a natural experiment. If you compare firms in digitally-ready districts to those in less-ready districts, before and after November 2016, you can isolate the effect of digitalization on firm performance. So, with the help of government data, Chen created an index to check the digital readiness of various districts.

The hypothesis was straightforward: did businesses in more digitally-ready districts perform relatively better after the shock, given how they could transition to digital operations more smoothly?

Services won, manufacturing lost?

Turns out, they could.

In districts with better digital infrastructure, services firms saw income rise by 1.3% and productivity jump by 8.4% relative to firms in less digitally-ready areas.

However, there was one very important nuance in this result.

While services firms won, manufacturing firms didn’t — even in the districts that were more digitally-ready. Manufacturing firms in those same districts saw income fall by 2.5% and productivity drop by 8.1%. This applied to both small and large firms. And this effect was hardly temporary, persisting for a few years post-demonetization.

When you think about it, it feels counterintuitive. You’d expect the cash crunch to hurt service firms more. These deal directly with consumers, who suddenly had no cash. Manufacturing firms, especially those with business-to-business models, should have been more insulated. Instead, the opposite happened: service firms in digitally-ready areas adapted and thrived, while manufacturers in those same areas struggled. Why?

Well, here’s the thing: the cash crunch indeed hurt services firms, which tend to have more consumer-facing operations. When a shock like demonetization hits, it effectively reduces the revenue firms can earn without going digital.

But here’s the funny thing: that also created stronger incentives for services firms to invest in digital technology.

That’s where the most important mechanism driving these stronger incentives comes into play — how India’s market for digital workers functions.

A talent war

As services firms invested more capital in digitalization, they also began aggressively hiring for workers with information and communications technology (ICT) skills. These would be people with degrees in computer science, software engineering, or other related fields.

Historically, India has always faced a chronic shortage of ICT professionals. The share of Indian employers struggling to fill ICT positions rose from 48% in 2012 to 63% in 2019 and hit 80% by 2023. Meanwhile, labor mobility across districts within India has always remained quite low.

As a result, the supply of Indian ICT workers is unable to quickly respond to a sudden increase in demand for ICT talent. Meanwhile, training new ICT graduates takes six years — if you want someone to enter this path, you have to start at the 11th grade, having them choose science, and then pursue a four-year degree.

With this immediate bottleneck, ICT wages in the services sector went up, way more than manufacturing.

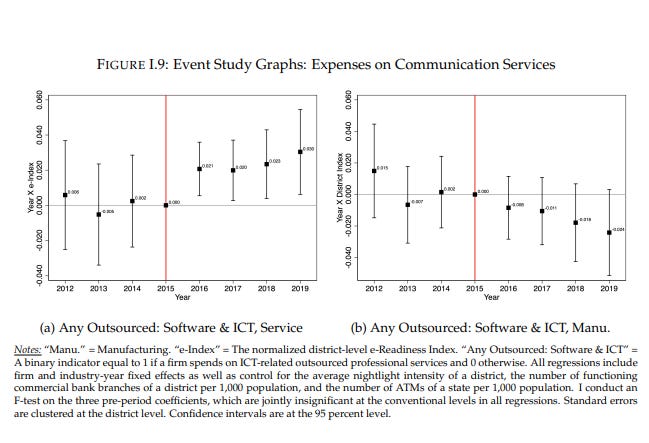

This feature of India’s labor market, as Chen finds, is key to understanding the demonetization shock. Firms that could go digital quickly had an advantage. With time, this transition became harder — as ICT workers increasingly became too expensive. After 2016, wages for ICT professionals rose by about 10% in more digitally-ready districts compared to less ready ones. But the wages for everyone else were basically flat.

More importantly, ICT workers started moving between sectors. In more digitally-ready districts, workers with ICT degrees became far more likely to work in services than manufacturing. After all, in contrast to services, ICT wages in manufacturing basically fell flat — even declined in certain areas. Service firms were basically bidding away the talent that manufacturers needed.

This, in turn, created a feedback loop between hiring and investment in ICT. But manufacturing firms, losing ICT talent to services, didn’t (or couldn’t) make similar investments. If anything, they pulled back on digital spending.

So, service firms in digitally-ready areas became more productive. Meanwhile, since high-skill ICT workers were now too expensive, manufacturing firms had little choice but to hire more lower-skilled labour — reducing their productivity.

Meanwhile, the inequality between ICT workers and other workers also widened year after year.

This creates a troubling dynamic for India’s industrial ambitions. There’s a possibility that a policy that accelerates digitalization also intensifies competition for scarce ICT talent. And in that competition, services win, sometimes at the cost of manufacturing.

Policy implications

India’s government has been pushing both digitalization (Digital India, UPI, Aadhaar-based services) and manufacturing (Make in India, PLI schemes). But, accounting for this paper’s results, there may possibly be some tension between these goals.

Chen’s study suggests that in a country with severe skill shortages and limited labor mobility, a sudden push toward digitalization will not have evenly-distributed gains. The service sector grows, while manufacturing struggles. Wage inequality widens, with gains concentrated among already well-paid ICT professionals.

None of this means digitalization is bad and shouldn’t be pursued. Nor does it mean that services growth and manufacturing growth do not go hand-in-hand. However, what Chen does emphasize is that how large-scale digitalization efforts work depends on the existing infrastructure and institutions in a country.

What would help? Chen points to a few solutions. For one, investing in digital infrastructure in less-developed regions would be useful. So would creating tax incentives for digital adoption in manufacturing. Expanding ICT training and education would help too, though the payoff takes years.

The broader lesson is that India’s growth model has structural features that keep reinforcing themselves. Services attract talent because they’re growing, and they grow because they attract talent. Many manufacturing industries, however, haven’t yet benefited from such a cycle. Breaking out of this pattern requires thinking carefully about how every major policy shock ripples through the labor market.

Tidbits

Adani Green plans to scale BESS at Khavda to 7+ GWh by FY27 (3.5 GWh by FY26-end) with ₹25,000–₹40,000 crore capex, using storage to mitigate grid evacuation delays and capture peak-power arbitrage from co-located solar.

Source: The Hindu Business LinePVR INOX will sell its 93.27% stake in gourmet popcorn brand 4700BC to Marico for ₹226.8 crore (all-cash), monetising a non-core asset to strengthen its balance sheet while Marico bolsters its premium snacking portfolio.

Source: The Hindu Business LineHindustan Copper has emerged as the preferred bidder for the Baghwari-Khirkhori copper block in Madhya Pradesh, after offering the highest price in a forward e-auction for a composite mining licence concluded on January 22.

Source: ET

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Mr. Pranav Manie

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

We need a dedicated post for Organisations and Companies to watch out for , which are going to lead the Energy transition in India , from deep-tech startups to Legacy Discoms!!!