India’s Manufacturing debate, VIP’s crisis & shrinking Insurance market | Who said What? S2E3

Hi folks, welcome to another episode of Who Said What? I’m your host, Krishna. For those of you who are new here, let me quickly set the context for what this show is about.

The idea is that we will pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualize things around them. Now, some of these names might not be familiar, but trust me, they’re influential people, and what they say matters a lot because of their experience and background.

So I’ll make sure to bring a mix—some names you’ll know, some you’ll discover—and hopefully, it’ll give you a wide and useful perspective.

With that out of the way, let me get started.

Sankaran Naren on the economy

Sankaran Naren of ICICI Prudential is one of India’s well-respected fund managers. We listened to a recent interview of his on NDTV Profit. There are a bunch of interesting things he said, but what got us to sit up is a very bold quote from him:

“The way we [India] have managed to become strong in services, we have to become stronger in manufacturing. Is there any country which has become strong in both? The answer is no.”

We had to ask ourselves, is this really true?

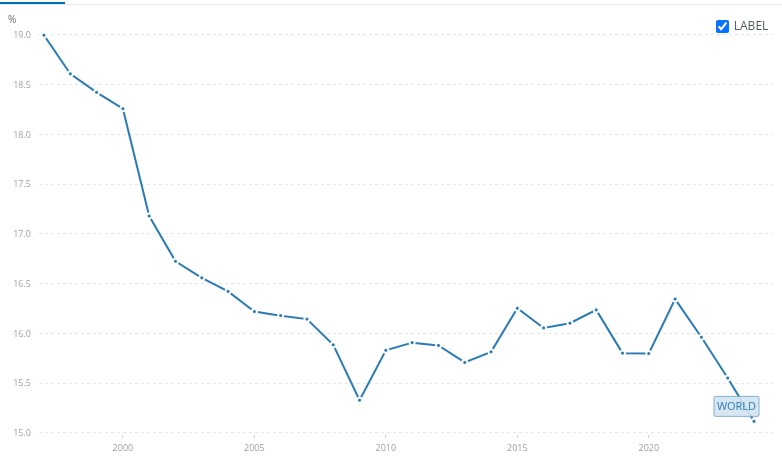

Well, manufacturing has declined across the world. It fell from 19% in 1997 to 15% last year. Much of the world seems to be de-industrializing a little too early.

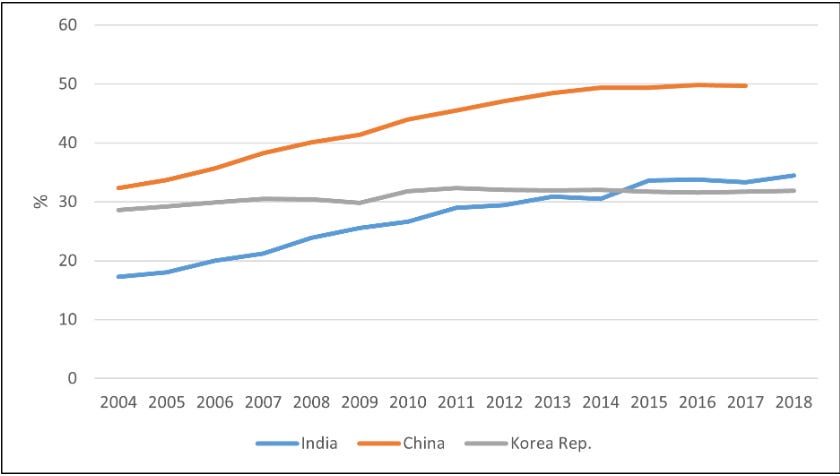

There are only a handful of sizable countries in the world where manufacturing makes up more than 20% of the GDP. China and Vietnam are around the 25% mark. There’s Japan, too, at 21%.

India’s share has reportedly stagnated over time, but our early success in services, especially IT is well-known.

Services have increased their share of the world’s output to 66%. It makes up a whopping 80% of the US’s output, while for China, it’s 60%. For Japan, however, that number is 70%. If we assume somewhat arbitrary numbers, China and Japan contradict Naren’s quote.

Let’s take the veil off the numbers, though. Both China and Japan have global e-commerce giants in Alibaba and Rakuten, and well-established telecom sectors. China has also had its own fintech revolution, and a huge tech sector that includes Bytedance, Huawei, and DeepSeek.

However, Japan imports most of its IT needs as its domestic software industry is weak.

If services just meant IT and tech, then Japan would be excluded.

But even then, what does this decline in manufacturing even mean? Both China and Japan have soared in GDP per capita compared to India. Their services output could be more valuable in absolute terms.

More importantly, the share of manufacturing is expected to fall as a country gets more productive. It does need to move resources to more high-value activities at some point.

But this might imply one other thing. More productivity would make goods cheaper and faster than services. Meaning that, relative to services, goods may add less value on paper. Economist Biswanath Goldar balanced out this price effect and concluded that India might be doing better than mere stagnation.

That’s promising. But the point of this is to show that our ideas of economic strength in certain industries can sometimes be arbitrary. The notion of being good at two very different industries at once sounds attractive, but what if those two industries take resources away from each other?

What should be measured is how India builds capabilities over time, and the choices we make in the process.

VIP is getting rid of its baggage

VIP Industries is going through a huge shift. The Piramal family, the promoters behind the company, are slowly stepping aside. They just agreed to sell a large chunk of their shareholding, 32% to a Private Equity consortium. An open offer will soon follow, allowing other shareholders to sell their shares to the same group. This is, in short, a complete regime change for the company.

What triggered this change? The company’s Chairman, Dilip Piramal, recently gave a surprisingly candid interview to CNBC TV18, spelling out the company’s five-year-long crisis and the hard math that went behind this shift.

He’s still proud of the company he has built, of course. As he says:

“India is the only country in the entire world where Samsonite is not a market leader even today.”

This is true. But VIP’s lead is also fragile. And as customer preferences change, they’re finding it hard to keep up. As Mr. Piramal says:

“My Bangladesh factory is such a great source of soft luggage. This market… has shifted drastically from soft luggage to hard luggage. So that has caused us problems.”

Demand patterns are changing. VIP’s existing capacity is built for stitched fabric cases, but that’s not what Indian customers want anymore. The company needs to make major investments and retool itself. But looking at its past trajectory, that seems unlikely:

“We have continued our market leadership but in the last five years, we have not been doing well. I would say we have had a management crisis in the last two‑three years and our market share is going down.”

That compresses a messy timeline. Three managing directors have quit since 2021. All through this time, the company bled market share to its rivals. Analysts now peg its slice of the organised luggage pie at roughly 38%, down from 47% just four years ago.

This also showed up in the company’s share price, as Mr. Piramal explains:

“That is the tragedy. Two years ago, the share was around ₹70,0 and the market cap was about ₹10,000 crore. We got an offer at that price but my management said the share price would rise 50 percent in a year and even 100 percent in two years. Unfortunately that hasn’t happened.”

Things just didn’t work out. As he said:

“Professional management was not being able to run it well… for the interest of shareholders, we needed a change of management and a change of ownership.”

But the biggest problem, perhaps, is the fact that the rest of the family simply isn’t interested in taking over. As Mr. Piramal says:

“The younger generation is not interested in the management. So what do I do? There is a theory of Peter Drucker, who was used to be the father of scientific, modern management in the ‘50s. … He had a very good theory that by the fourth generation of family businesses, they either degenerate or they lose interest and that happens very often… So there was an absolute need in my case to have a change of uh ownership and management.”

But here’s the big question: can private equity do any better?

Insurance sector is bleh????

Sridhar Sivaram, the investment director at Enam Holdings, has been openly critical of India’s life insurance companies for a long time.

“I remain bearish on insurance,” he said on a recent interview with NDTV Profit, “for the simple reason that this is a very opaque industry. Nothing that they disclose are actual numbers. Everything is an estimate. Embedded value is an estimate. Their profits are an estimate… nothing is real.”

Think of embedded value as a guess of how much profit an insurance company might make in the future from the policies it has already sold. The only reason he’s wary. He adds:

“The number of lives covered for the top four life insurance companies last year fell by 30%. I still don’t have an exact answer why they have fallen so much. These are not normal numbers. You don’t suddenly reduce [coverage for] 5 crore people.”

It’s true. In FY25, around 5 crore people lost life insurance coverage, nearly a quarter of all lives covered the previous year. That’s not a rounding error—it’s one of the steepest year-on-year declines ever.

In the past, such a sharp drop in coverage usually happened only during major shocks, like the COVID pandemic, when economic disruption forced insurers to pull back. But this time, there was no such trigger. It wasn’t a pandemic or a sudden regulatory ban. Instead, it was a self-inflicted crisis rooted in the collapse of microfinance-linked group insurance.

See, I am not an insurance expert. But if he’s right that embedded value (EV) is full of assumptions and isn’t a reliable metric, does that mean “number of policies sold” is a better yardstick?

It seems intuitive: fewer policies = less coverage = shrinking business. But in the case of life insurance, that logic breaks down because not all policies are equal. What fell by 30% last year wasn’t high-value individual term insurance. It was mostly group-linked credit life policies.

A group-linked credit life policy is basically what lenders bundle with loans. For example, if a microfinance institution gives a ₹30,000 loan to a borrower, it might automatically attach a small one-year life cover to it. That counts as one “life covered.” These are short-term, low-ticket, and tied directly to the loan lifecycle. Once the loan ends, the cover lapses. So when lenders slow disbursements or insurers find the segment unprofitable, volumes drop sharply.

But here’s the thing: while group-linked credit life may bring volume, it contributes little to revenue.

Just to put this in context: take HDFC Life’s FY25 product mix. Over 60% of its Annualised Premium Equivalent (APE) comes from just two product categories — Participating policies (traditional savings plans with bonuses) and Unit Linked Insurance Plans (ULIPs).

If you’ve made it this far, please let me know if you have any feedback for me 🙂

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Insurance is a great business. When it is tied with credit and home, it is not full services insurance. Similarly in case of ULIP also the insurance is not for longevity of person, but for longevity of investing. Hence there are two components, one is pure insurance where I pay for it every year, and another is LIC type where normally the coverage period is above 25 years. Also the amount insured should also be a metrix for assessing the sector. Lastly govt and agencies should drive a campaign as INSURANCE is Necessary.

Regards

Sir,I subscribed today and was charmed with Deep Insights in such a convincing manner (with original words that matter).I must say ZERODHA Excels in whatever it does. I had earlier subscribed to many financial newsletters and out of frustration about content,I unsubscribed them all.Now I’ve access to “The Daily Brief”