India’s Infra projects were Broken—Until Now

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The sector that is building India

A European icon hits a wall… and Bajaj comes to its rescue

The sector that is building India

Recently, we came across a small, rather esoteric update from Care Edge: about a small change in bidding norms. It almost seemed too trivial to care about — it talked about changes in performance securities. But the challenge it was trying to address caught our eye. It was trying to save lakhs of crores in taxpayer money, and speed up government projects.

So, we decided to take a closer look. And that sent us tumbling through an extremely interesting, extremely complicated rabbithole. As we dug deeper, we realised that this minor update opened a window into a much bigger story: one of how India is building itself.

So we did what we always do: we rolled up our sleeves and tried to figure out how it all works. And this is what we ended up with — a deep dive on the Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) sector — one sector that’s both indispensable but, at times, dangerously brittle.

Let’s dive in.

The challenge of building modern India

In recent years — especially after the COVID-19 pandemic hit — India has been on a capital expenditure spree. In recent years, in fact, construction has fuelled a major part of our economic growth — roughly in the range of 7-10% of the gross value that has been added in our economy. This is, in great part, because the government is pouring large sums of money into infrastructure — building freight corridors, highways, seaports, and more. Through all this, construction has become an increasingly important part of our economic story.

All of this is in the service of one simple fact: we’re a country that is rapidly growing richer, more populous, and more urban. This is a tremendous tailwind for economic growth, of course. As an ever-larger part of India gets enmeshed in our economic networks, that’s bound to show up in our GDP numbers. But there’s a catch: if we hope to give all these people a life worth living, there’s a lot of work to be done. Our infrastructure simply isn’t up to the mark.

And so, we’re building. We’re building homes for people to live in, we’re building power lines and water supply, we’re building roads and trains for them to move around, and we’re taking up major logistics projects to string it all together into a cohesive economy.

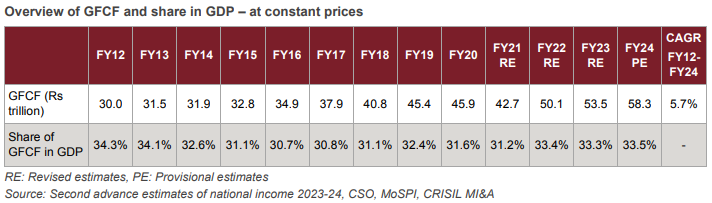

We know we spend a lot of time on this newsletter complaining about India’s chronic inability to pull in investment to serve our growing population. That remains true; we haven’t seen the sort of rapid national build-up that so much of Asia saw in the last few decades. But that doesn’t mean we’re sitting idle: it’s just that the total investment into India is growing at 5.7% — a healthy but not breakneck pace.

Much of this investment is being front-loaded by the central government, through its “National Infrastructure Pipeline”. The central government is pumping lakhs of crores (~INR 147 lakh crore planned ahead) into a generational infrastructure build-up. With this robust warchest in place, it’s tackling all sorts of projects — power, water, transport, housing, and more.

Roughly 72% of those projects — a pipeline worth a gigantic INR 92 lakh crore — are likely to go through what’s known as the ‘EPC’ route: Engineering, Procurement and Construction. That’s what we’re going to talk about today. In short, there’s a multi-billion dollar market in building the future of India, and its one of the most complex spaces we’ve tried wrapping our heads around.

Now, don’t get us wrong. This government build-out isn’t the only source of demand for the sector; it’s just one source of demand. There are also state projects, and complex industrial projects like gigafactories. Many EPC companies are also servicing international projects — taking their construction chops to the Middle East, Africa and South East Asia.

The backbone of the sector, however, remains with these central government projects. Among other things, that’s where you have the lowest counter-party risk. And as we’ll soon see, this is a business where you want as little risk as possible.

What in the world is EPC?

There was, once, an old way of building a major project. Each project would have an owner — often a government entity — that would try doing everything itself.

The owner doubled up as a project manager. They would plan and design a project — either themselves, or by getting a special contractor for design. They would buy all the materials and equipment. And then, they would engage multiple contractors or specialists to handle the on-ground execution. The owner bore all the headaches: delays, price changes, cost overruns, and all sorts of other issues. And all the outcomes of Murphy’s law — like exchange rate movements making a component too expensive — was a risk the project owner took.

This is difficult even for small-scale projects — if you’re ever frustrated by how slow or shoddy government work is, you’ve experienced that first-hand. But if anything, over time, our ambitions have grown. We now want to build world-class highways, airports, solar parks, and the like. The government has neither the expertise nor the patience to handle the complexity of such a project. So what can it do?

There’s no one answer, really. Fundamentally, the government (or any other owner) needs a way of giving away some of the headache of managing and executing something complicated. We’ve played around with all sorts of models to do so, from “Build-Operate-Transfer” (BOT) models, to “Hybrid Annuity Models” (HAM). In essence, all of them entrust private companies with more of the work of managing tough projects, for better pay. But you can’t give away too much risk either — investors tend to stay away from too big a burden. So the question is: how much risk can you hand over to a private firm? Where does the right equilibrium lie?

Perhaps the most successful model to emerge, over the last few years, is the “engineering, procurement and construction” model. Here, an owner gives out contracts to companies that work as a ‘one-stop-shops’ to manage entire projects.

The owner’s role, here, is limited to setting a broad goal, like “build a highway in 2 years, within ₹500 crore”, and getting out of the way. From that point, it’s merely making periodic payments. The contractor takes care of everything from designing the project, to buying materials, to sub-contracting individual bits of execution. More importantly, it is these contractors that now put their head on the line for delays, excess costs and more.

These are sometimes called ‘turnkey’ projects: as an owner, you contract so much out that, at the end, all you have to do is “turn the key” and the project starts running.

This is a model we’re increasingly adopting for all kinds of projects. Here are just a few:

Power transmission and distribution: All sorts of power projects, from setting up power plants, to transmission lines, are regularly taken up on an EPC basis. Aside from the broader project of electrifying India, we’ve unlocked a lot of new demand in this sector off-late as well, because of the green transition. To do so is to set up massive projects — solar farms, wind parks, green hydrogen projects, and the like — most of which work on an EPC basis.

Transport: India’s biggest infrastructural goal, arguably, is its massive transportation build-out. We’re building roads, trains, ports, airports, urban infrastructure and more. The scale of this leap is massive. We’re constructing roads and highways at the scale of tens of thousands of kilometers a year. Similarly, there are currently thousands of urban transportation projects — like metro networks, bus terminals, airports and more — that are currently being carried out by EPC contractors.

Water: We’re relying heavily on the EPC model for major water supply projects. This includes both domestic water supply, through schemes like the Jal Jeevan Mission, and agricultural water supply.

This is just a sample, of course. There are a variety of other projects that are built through EPC contracts — from complex industrial projects, to defence structures.

How do you run an EPC business?

To tell you the truth, the EPC business is one of the more complex ones we’ve reckoned with. It’s a minefield of complexity and risk, where everything depends on the specifics of what you’re trying to do.

If you’re running an EPC business, here’s everything you have to do. And mind you, we’re leaving out a lot of nuance.

Line up your order book

To begin with, if you’re running an EPC business, you need to line up orders. To bag an order, you have to track and bid for tenders. Most tenders carry a set of qualifications: some, which showcase your technical abilities, and some that point to your financial position. Of everyone that qualifies on both grounds, usually, the lowest bidder wins.

Any work you take up today will keep you occupied for a few years. So, at any given time, you probably want an order book that’s several times (3-4x) as large as your yearly revenues.

You want to diversify these as much as possible. You probably want a range of clients, across several geographies — because at any time, any of them could cause you problems.

Now, your best case scenario is to directly win an entire project from the owner. But if you’re not big enough for that, don’t worry. You can sub-contract. Most entities that win EPC contracts don’t have the wherewithal to complete the entire project by themselves. So they might break the project into smaller parcels and contract those out. You can fight for those contracts, at least until you make your way up the chain.

Find enough finance

To cater to EPC contracts, you need to arrange for enough capital to keep you afloat.

The amount of money you need to put up really depends on the kind of project you’re bidding for. If it’s a BOT project or an HAM one, for instance, you need to bring your own financing for the project. For that, you might need to find upfront “equity” capital to put up.

EPC projects are somewhat simpler. But they’re by no means easy.

For one, even for an EPC project, you need to furnish a variety of bank guarantees at multiple stages: for instance, you need a separate bank guarantee at the time of bidding, a different performance guarantee, another guarantee to have money released, and more. All of this eats up the amount of bank financing you can arrange for the project itself.

Beyond that, you have to find enough money to take care of your working capital needs — which can be massive, given the scale of what you’re attempting. This makes working capital management a long-standing problem for EPC players. To get around this, companies fall back on all kinds of banking arrangements, from letters of credit, to invoice discounting. How well one can manage cash, in fact, is perhaps one of the biggest ways for EPC companies to distinguish themselves from competitors.

Sometimes, the project owner might also give you a “mobilisation advance” — 5-10% of the contract amount — to get everything started.

Getting land

Major infrastructure projects, almost by definition, require a lot of land. And often, that land belongs to people who don’t want to part with it. So, EOC projects can often get tied down even before they begin, because the government needs to arrange the fair compensation and rehabilitation of anyone whose land you might impinge upon. All of this sets you behind on your project timelines.

This is a problem that the government is quite aware of. Unresolved land, in fact, is perhaps the biggest reason for EPC projects running into trouble. The government is trying to get around this by acquiring land in advance for major EPC projects. We’re also evolving strategic utility corridors, where the same strip of land hosts multiple projects.

But for someone in the EPC business, this remains one of the big headaches you should prepare for.

Get past regulatory hurdles

EPC contracts involve major, and deeply complex construction work. Naturally, projects of this size are governed by all sorts of regulations.

Environmental regulations, for instance, can delay many projects. To begin with, you might have to carry out an Environmental Impact Assessment, and get forest clearances. Before you can break ground on a project, you also have to get the necessary consents from pollution control departments. Because your projects involve substantial amounts of manpower, you may need to get a series of labour approvals in place, and demonstrate compliance with safety regulations. And so on.

All of this can drag down your timelines.

Execution

It’s only once all this is done — once all the paperwork and financing is out of the way — that your real work starts.

An EPC project is typically divided into three phases. First, comes the ‘’engineering phase”, where you plan everything out. You figure the design and engineering of the project, and get all your technical drawings and specifications in place. Next comes the “procurement phase” — where you purchase all the necessary equipment, materials, and services. Only then comes the actual “construction phase” — where you carry out all the works you have to, put in all the necessary equipment and bring the project to a close. All of this is your headache. Your client’s only concern is whether you can turn in a functional project at the end of it all.

Once you bag a contract, it’s on you to make it as efficient as possible. It’s your job to make sure that your plans are as practical as can be. You have to get your materials at the best possible cost — sometimes setting up entire supply chains for a single project. And it’s up to you to make sure things happen on time. The better you plan your execution, the better your margins are likely to be.

There are certain hurdles that are common to any EPC project:

For instance, a big part of your business revolves around managing a vast army of labour. This might include semi-skilled workers like welders, electricians, masons, or heavy equipment operators. EPC contractors face a constant shortage of these workers. You also need to create facilities to house this workforce properly.

A lot of your expenses can go into buying basic construction materials, like steel, bricks, cement etc. This means that your business is usually at the mercy of commodity cycles. When those prices come down, as they did in 2023, costs become much easier to manage. That said, what you spend depends entirely on what you’re trying to build. For some contracts, a major part of your expenditure could go into arranging highly specific, and expensive, equipment.

Beyond this, though, different projects bring very specific execution challenges with them. Some of these can turn into a full-blown project by themselves. For instance, imagine you’ve been roped in to setting up a rail line in the North Eastern mountains. Getting the necessary equipment, like 30-40 meter girders, can turn into a complex task that requires substantial coordination.

And besides all this, there’s no end to the number of things that can go wrong — everything from natural disasters, to geopolitical events can throw your project into jeopardy.

Perhaps your biggest challenge, though, is keeping an eye on your finances. While you have to put up a lot of money upfront, you’ll only be paid pre-agreed amounts for reaching milestones. And this is where you face one of the worst challenges of this business: cash actually reaches your bank account with a lag. In between, you’re constantly sitting on a huge counter-party risk.

If a project moves slowly, or if payments stop coming in, no amount of operational cleverness will save you. If you run out of working capital, a project can suddenly stall in its tracks.

The intense competition for EPC contracts

Because of how challenging EPC contracts are, the sector is dominated by a small set of giants: Larsen and Tuobro, Shapoorji Pallonji, Adani, and the like. The scale of these companies is an advantage in itself: they have massive balance sheets, access to cheap financing, and they’re big enough to diversify across a range of projects — making it much easier to survive the chaos of this business.

But the field is no oligopoly. There’s a long tail of smaller players that try focusing on niche areas or projects. Because of the sheer number of such entities, the sector remains rather fragmented, and massively competitive. And this creates a unique problem for the sector: it is sometimes too competitive for the margins to make sense.

There’s a fundamental problem with tendering, as a mechanism: it rewards under-cutting and making tall claims. Your bids don’t just reflect your operational chops — it also reflects your risk appetite. You might under-cut someone on a project because you think you can streamline things and do it better than them. But you may also do so simply because you’re more optimistic about navigating all the crises you might face down the line, and are more willing to run the risk of the project falling apart.

If that calculation turns out to be wrong, the project can run into serious problems.

This risk becomes much worse because it’s a space dominated by one buyer — the government. Whenever the government cuts down on infrastructure building, things gets worse. Suddenly, the entire sector finds its order books empty. Companies begin bidding for random projects to diversify their revenues.

Recently, for instance, there was a slight lull in awards for national highway construction. The sector was hit by a double-whammy — the longer-than-usual monsoon made it harder to take up construction projects. Meanwhile, the government’s attention was absorbed by the Lok Sabha elections. Project awards under the Bharatmala project, for instance, fell by 20% year-on-year in the first eight months of FY 2025, because approvals simply weren’t coming through. Companies that depended on these projects suddenly began to bid for any other contract they could get their hands on.

The few tenders that were open, meanwhile, saw an unprecedented number of bids. Sample this tidbit from Ircon International’s most recent earnings call:

Coda: The new changes

And that, finally, brings us back to where we started.

The government is well aware of these problems. It knows that if EPC players bid too aggressively — quoting prices that simply don’t make sense — the government eventually gets no benefit from those prices. Usually, contractors just end up cutting corners or leaving projects incomplete.

That’s why the MoRTH has stepped in. They’ve scrapped the old 3% cap on Additional Performance Security (APS) — the extra money contractors have to put up when their bid looks suspiciously low — and brought in a new framework that applies across all central government road projects. Under this new system, if a contractor bids too low, they’ll have to back it up by committing more of their own money as a guarantee. Think of it as a way of testing how serious someone is: you can’t just say you’ll do something for cheap; before that, you’ll need to put something on the line. The hope is simple: with higher skin in the game, bidders will think twice before submitting risky bids.

Will this fix all the challenges in India’s EPC sector? Of course not. After all, this sector only exists because such projects are difficult to pull off. But it does bring more sense to the system. It ensures that people are less likely to make promises they won’t deliver. In the end, that’s what really matters: building a modern India isn’t just a question of announcing projects on paper, but creating a living, breathing infrastructure network that works for the millions who rely on it every single day.

A European icon hits a wall… and Bajaj comes to its rescue

Something quite unexpected recently happened in the space of motorcycles.

One of Europe’s most famous motorcycle companies, Pierer Mobility AG - which owns brands like KTM, Husqvarna, GasGas- found itself in such deep financial trouble that it had to file for insolvency protection. That basically means it couldn’t pay back its loans on time and needed help from the courts to avoid shutting down completely.

Bankruptcies are nothing unusual in the world of business, of course. But here’s the twist. An Indian company, Bajaj Auto, stepped in to rescue them. The company has agreed to put in roughly ₹7,600 crore for their rescue. But this isn’t just a friendly favour. It’s a deal that will give Bajaj majority control of the company. In other words, KTM, an iconic European brand, could soon be run by an Indian company.

To understand how this happened and why it matters, we need to take a few steps back.

What makes them special?

Pierer Mobility AG is Austria’s biggest motorcycle maker — and the 33rd largest company, by market capitalisation, on the Viennese Stock Exchange.

It’s an interesting sort of company: unlike other two wheeler-focused companies like Honda or Yamaha, that make a bit of everything — from scooters to commuter bikes to superbikes — they do just one thing. They build high-performance motorcycles. Its entire offering is fast, aggressive machines made for racing, off-roading, and thrill-seeking.

Bikes that look like this:

KTM has always put racing at the centre of its brand. It boasts a big presence in MotoGP — the world’s top motorcycle racing league. Estimates suggest KTM spends around roughly ₹665 crore a year just to participate in MotoGP. That isn’t just for the love of sport, of course. It’s a way for KTM to prove that its engineering is world-class and gives it the admiration of bike-lovers across the world.

While all that sounds impressive, it also reveals a deeper issue. Focusing only on high-performance bikes comes with big risks. These bikes are expensive to design and build. They don’t sell in huge volumes. And when the economy slows down or inflation rises, people stop spending on luxury motorcycles.

Put simply, when you're worried about your electricity bill or home loan EMI, you're not going to buy a ₹10 lakh superbike.

This challenge has haunted KTM for a long time. In fact, this is the third time in its history that the company has come dangerously close to collapse.

The first fall, and the first comeback

KTM first went under in 1991. Back then, it was mostly making smaller, affordable bikes. But a series of failed bets and tighter regulations triggered a financial collapse. The company ran out of money, and was soon forced into insolvency.

KTM’s revival came through an interesting strategic shift. It decided to focus only on performance, which allowed it to command a premium. Racing and engineering became the core identity. That worked well. KTM began to stand out as a premium performance brand.

But with that, it also became heavily dependent on a niche. Its bikes remained expensive and were hard to scale in emerging markets like India, where most buyers still look for affordability and mileage.

That’s when Bajaj Auto first saw an opportunity. In 2007, KTM partnered with Bajaj, giving Bajaj a minority stake in the company. More importantly, Bajaj got the rights to manufacture KTM’s smaller bikes in India.

This was a turning point for both companies.

Bajaj brought in cost-efficient, high-quality manufacturing. KTM brought in brand value and world-class engineering. Together, they were able to build bikes that were affordable to produce, but still felt premium. This partnership clearly worked for Bajaj, because over time, it kept increasing its stake, until it owned about 49.9% of Pierer Bajaj AG — the holding company of Pierer Mobility AG.

KTM’s bikes were now being made in India and sold across the world, including in Europe and the US. India became KTM’s factory. Austria remained its brain centre for innovation and design.

Success leads to overreach

But that success may have made KTM a little too ambitious. The company expanded into electric bicycles, sports cars, and kept raising its MotoGP spending. These new moves were expensive, and not all of them worked.

One major mistake was betting heavily on electric bicycles. During the pandemic, there was a spike in demand, and KTM jumped in. But the demand faded quickly, catching KTM off-guard. It was left with unsold inventory worth roughly ₹9,500 crore. Meanwhile, it was still spending huge amounts on R&D and racing.

The finances started spiralling yet again.

By 2024, KTM found itself facing an unprecedented crisis. Despite maintaining significant revenue streams, the company’s annual revenues could only reach around ₹19,000 crore, which was overshadowed by its daunting debt burden of nearly ₹15,200 crore.

Things kept getting worse from there. Global motorcycle demand plummeted, causing KTM’s sales to collapse by 22% in a single year. The resulting stockpile of approximately 2,30,000 unsold motorcycles forced KTM into an operational halt. Its production lines went silent for three full months as the company struggled to clear excess inventory. The severity of the crisis became evident when Pierer Mobility AG publicly warned shareholders that its equity had been nearly wiped out, with losses amounting to half of the share capital.

Compounding the company’s problems were its looming debt obligations. Specifically, the company had bonds worth around ₹3,300 crore, which were quickly approaching maturity. KTM lacked the necessary liquidity to meet these critical repayments.

Facing this mountain of financial pressures, KTM, alongside its parent company Pierer Mobility AG, took the drastic step of filing for insolvency protection in Austria. The Austrian judiciary intervened decisively, stipulating clear and stringent terms for survival: KTM was required to repay at least 30% of all outstanding dues by May 2025. Failure to meet this court-mandated repayment would inevitably trigger complete liquidation, effectively forcing KTM out of business permanently.

What was a crisis for KTM, though, was an opportunity for Bajaj. KTM was a brand they had spent nearly two decades helping to build. Letting it fail would be a huge setback. But rescuing it would mean something bigger — owning one of the world’s most respected premium motorcycle brands outright.

And that’s exactly what Bajaj went for.

The Deal Mechanics

Bajaj Auto is helping Pierer Mobility with a rescue package of about €800 million.

But it's not simply paying off Pierer's debts outright. Instead, Bajaj provided an immediate emergency loan — bridge financing — of €200 million to stabilize Pierer immediately. The remaining €600 million will be arranged as secured loans raised by Pierer Mobility — but Bajaj is guaranteeing this debt. Essentially, Bajaj is standing behind Pierer’s debt, promising lenders that they'll get their money back, which makes it safer for them to lend.

Is Bajaj doing this all for free? Of course not!

In return for helping stabilize Pierer Mobility, Bajaj receives a special right—a call option. This option lets Bajaj buy a 50% stake in Pierer Bajaj AG –- the parent entity, that owns 74.9% of Pierer Mobility. Bajaj can decide if they want to exercise this option anytime until May 31, 2026 and purchase the stake for €50.7 million. If Bajaj uses this call option, they will gain majority control of Pierer Mobility (and its brands KTM, Husqvarna, and GasGas). Whenever that happens, Stefan Pierer, KTM’s current CEO, shall step down from actively running the business.

This isn’t just an opportunistic financial play. It fills a long-standing gap in Bajaj’s global strategy. Bajaj has always been strong in the commuter segment in India, with bikes like the Pulsar and Platina. But it never had a global premium brand under its own name.

With KTM, it now gets everything at once — a premium brand, a global dealership network, and access to advanced electric vehicle tech.

Building that from scratch would have taken years and cost far more.

What’s in it for KTM?

For KTM, this deal is a lifeline.

Manufacturing in Europe had become too expensive. By shifting more production to India, KTM can cut costs without compromising on quality. Bajaj already handles production for the smaller bikes. Now, even mid-sized models could be manufactured in India.

But Bajaj isn’t going to do so blindly. It’s taking a hard look at KTM’s loss-making ventures. The electric bicycle business may soon be sold or shut. Even the expensive MotoGP program is on the block. The goal is to bring discipline and financial stability without losing KTM’s performance-first image.

What this could mean

If all this works out, it could shake up the global motorcycle market.

A leaner, more efficient KTM backed by Bajaj could become a real threat to brands like Royal Enfield, especially in the mid-range segment. It could also push Indian manufacturers to aim bigger and think more globally.

But this won’t be easy.

Running a global brand across continents is a complex task. Costs must stay low. The brand must still feel premium. Electric vehicles are rising. And motorcycles don’t have the same aspirational pull everywhere, especially with younger consumers.

Managing all of this will be tricky.

But if any combination can pull it off, it might just be Bajaj and KTM — one with scale and money, the other with brand and engineering. Designed in Europe, built in India, and sold across the world.

Tidbits

Coal India Files IPO Draft for CMPDIL; To Sell 71.4 Million Shares via OFS

Source: Reuters

Coal India Ltd has filed draft papers to list its subsidiary Central Mine Planning and Design Institute Ltd (CMPDIL), marking a key step in its divestment strategy. According to the draft prospectus, the IPO will be an offer-for-sale of up to 71.4 million shares, with no fresh equity issuance by CMPDIL. The company, which provides consultancy services in mine planning and coal exploration, is touted as India’s largest coal and mineral consultancy. The IPO will be managed by SBI Capital Markets and IDBI Capital Markets & Securities. This move follows Coal India’s broader plan to list subsidiaries, with activities for Bharat Coking Coal Ltd (BCCL) also said to be underway. CMPDIL’s listing comes amid a cautious IPO environment in 2025, as many companies have slowed or scaled back their public listing plans due to weak investor sentiment.

India Restores RoDTEP Scheme; ₹57,977 Cr Disbursed Till Date

Source: Reuters

The Indian government has reinstated the RoDTEP (Remission of Duties and Taxes on Exported Products) scheme, effective June 1, to boost export competitiveness. Initially introduced on January 1, 2021, the scheme was paused on February 5 this year for a policy review. According to the Commerce Ministry, total disbursements under RoDTEP stood at ₹57,977 crore (approximately $7 billion) as of March 31. The scheme reimburses exporters for embedded taxes and duties not covered under other refund mechanisms. With its return, eligible sectors including textiles, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, automobiles, agriculture, and food processing are expected to benefit. The revised version will operate on a digital platform to enhance transparency and efficiency. The decision comes amid India’s broader trade push, including recent agreements with the UK and ongoing negotiations with the U.S.

VST Tillers Unveils Electric Power Tiller and Weeder, Targets FY26 Launch

Source: Business Line

VST Tillers & Tractors has announced the development of two fully electric agri-machinery products — a power tiller and a weeder — slated for market launch in FY26. Both products are being developed in-house and come after three years of supplying electric drivetrain components to US-based Monarch Tractor. In FY25, VST sold 37,297 power tillers, up from 36,480 units in FY24, while weeder sales jumped 63% year-on-year to 7,458 units. The electric models are designed for a 4-hour runtime and offer fast charging capabilities, reaching 70–80% charge in 30–40 minutes. While battery swapping will be optional, the primary focus remains on rapid recharging to match existing usage patterns. The company has not disclosed pricing or margin expectations for the upcoming models.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Anurag.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Introducing “What the hell is happening?”

In an era where everything seems to be breaking simultaneously—geopolitics, economics, climate systems, social norms—this new tried to make sense of the present.

"What the hell is happening?" is deliberately messy, more permanent draft than polished product. Each edition examines the collision of mega-trends shaping our world: from the stupidity of trade wars and the weaponization of interdependence, to great power competition and planetary-scale challenges we're barely equipped to comprehend.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Can you do a newsletter where you can describe that how systematically you guys do research and where to get data and how to make report like you, for education purpose , I am a regular reader.

How does increasing the PBG help in more skin in the game?

There's no cash outflow in a PBG. its a commitment from the bank on your behalf