India's deadlock on pricing internet from satellites

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s deadlock on pricing satellite internet

The Missing Middle in India’s Energy Story

India’s deadlock on pricing satellite internet

It’s been a few months since we covered Starlink’s approval to operate in India, but it isn’t operational yet. So, what’s the holdup?

Well, getting Wi-Fi beamed down from space isn't merely about building satellites and orbital mechanics. The real drama is happening on planet Earth, in the state offices of Delhi. Bureaucrats there are wrestling with a question that only sounds simple, but really isn’t:

How should we price the right to beam internet from space?

The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) has made a set of recommendations on satellite spectrum pricing, based on consultations with private players. However, the Department of Telecom (DoT) has suggested that TRAI rework the set.

This is no mundane regulatory back-and-forth. What it really reflects is the incentives and goals of the TRAI, the DoT, and different private sector firms — and how those goals conflict with each other. This story won’t solely be about individual players Starlink, but the whole maze of pricing India's satellite spectrum.

Let’s launch.

Auction, or no auction?

Whether internet signals should be transmitted from space or land completely changes how it should be priced. And that’s the core of this maze. But before that, let’s understand what internet signals even are.

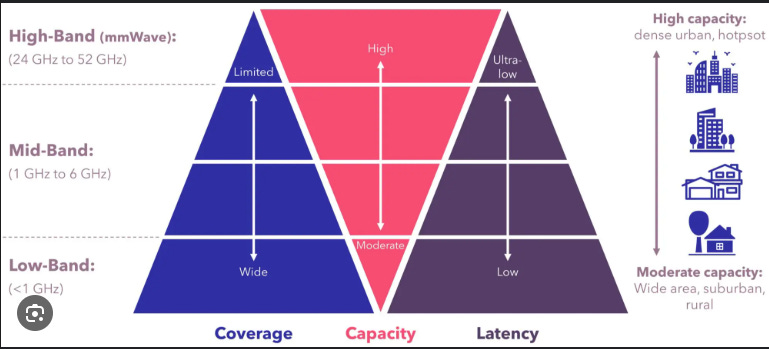

They are basically radio waves which have their own frequencies. Each frequency decides how much data the signal carries, and how widely it is broadcast. For instance, low-frequency waves (below 1GHz) travel far and are focused, but don’t carry a lot of data — making them useful for smartphones. High-frequency waves (above 24 GHz), on the other hand, carry a lot of data but don’t cover enough ground.

Now, let’s get down to Earth.

To transmit good internet to cities, mid-frequency waves — decent coverage with enough data — make the most sense. Your home Wi-Fi (2.4-5 GHz) usually operates in this band. However, when two signals in the same frequency band are targeted in the same area, they interfere with each other. Imagine two radio stations on the same frequency in the same city — you’d get nothing but static. Turns out, the internet works in much the same way.

That's why telecom companies auction for exclusive rights to use a frequency band (or spectrum) in a given area. It's like getting the sole right to use a specific highway lane in a specific city. Naturally, this drives up auction prices. And telecom firms like Jio and Airtel have spent tens of billions of dollars each on these auctions.

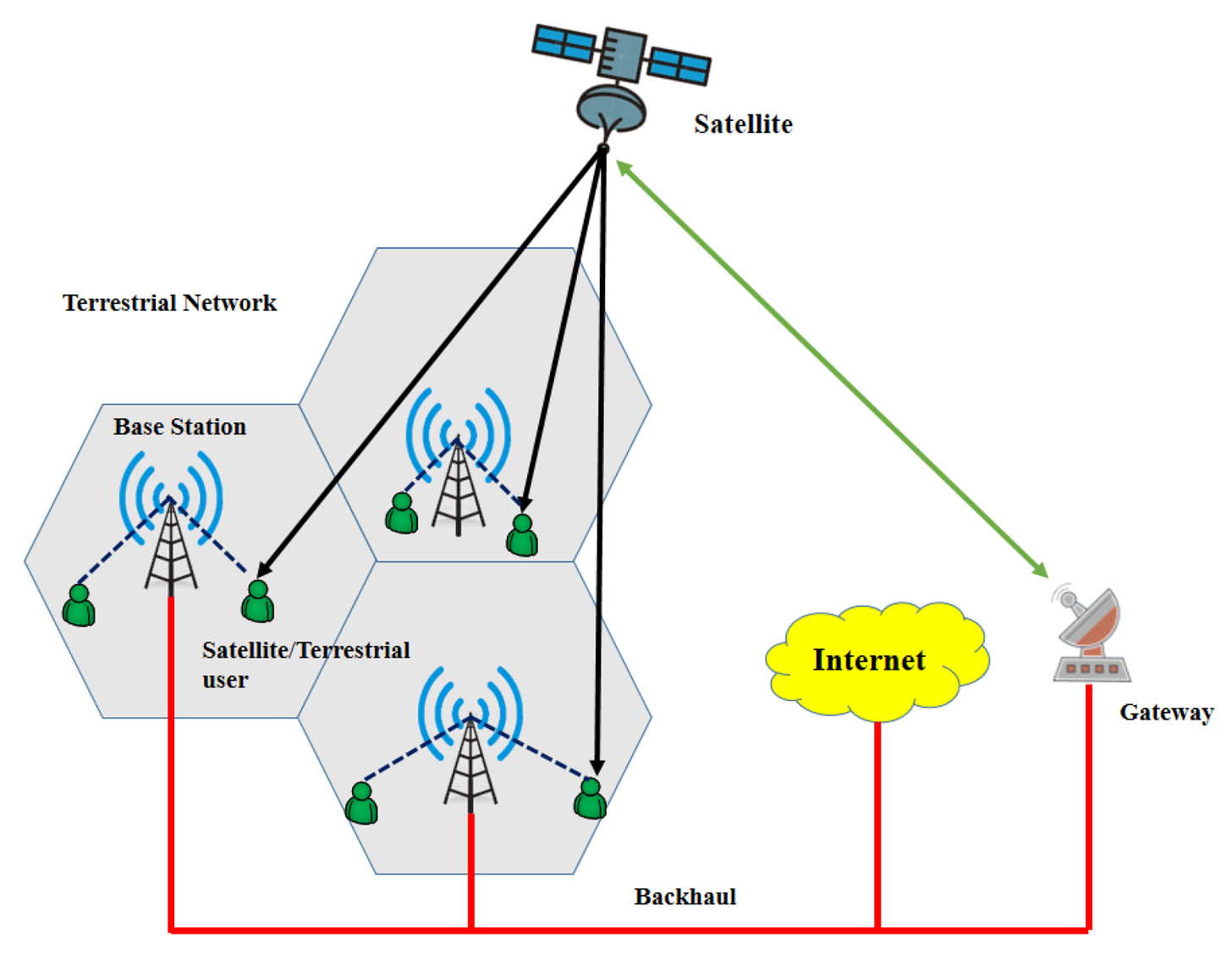

But satellite internet works differently.

Instead of broadcasting broadly across a city, satellites use incredibly narrow, focused beams—think laser pointers rather than floodlights. A satellite orbiting over one area in Bangalore can send internet to it, while another satellite can use the same frequency to serve another area in the same city. No static, no interference, just high-speed internet.

In other words, space increases abundance where land couldn’t. Now, everyone can use the same highway lane. And if that’s true, then do we even need auctions to distribute highways, or even internet capacity?

This is why almost every major satellite-operating country in the world—from the US to China—uses administrative allocation instead of auctions for satellite spectrum, all coordinated by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU). The national government sets the price (and rules), and companies adhere to it. Officially, India has also codified the same approach in the Telecom Act of 2023.

TRAI's latest recommendations follow this global template. Here’s the highlights from their list:

Satellite operators pay 4% of their adjusted gross revenue (AGR) as charges for using the spectrum, with a minimum annual fee of ₹3,500 per MHz.

For urban customers, there's an additional ₹500 annual charge per subscriber, so that rural customers may be subsidized. Currently, Starlink is extremely expensive for most of India

The spectrum would be allocated for 5 years, extendable by 2 more based on conditions. Interestingly, Starlink had lobbied for a 20-year allocation

A subsidy for one-time installation of satellite terminals

A multiplayer Mexican standoff

This is exactly where things get spicy. Not everybody in India's private sector agrees on how satellite spectrum should be priced.

On the side of administrative allocation are most private players (many of them foreign), like Starlink, Amazon's Kuiper, and even Bharti Airtel. Their logic is straightforward—this is how satellites work globally, and trying to auction shared spectrum would actually create artificial scarcity while also inflating prices.

The side of auctions, however, is primarily being led by India’s largest telecom operator, Reliance Jio. They’re extremely vocal about how much they don’t like administrative allocation. And they have counter-arguments as well — we’ll cover the most important ones.

Jio on the attack

Jio's first, most important counter is actually personal — they say that administrative allocation would be deeply unfair to them. We had the same question as you: why would India’s biggest telecom company say that?

Here’s their logic: to the end consumer, internet is internet, no matter if it comes from satellites in space or towers on land. That means satellites and towers will likely compete against each other. And Jio has paid over ₹1.5 lakh crore in auctions for towers, giving us an abundance of 4G data on our phones for dirt-cheap. But, under administrative allocation, satellite operators could get away with far lower costs, making it an uneven playing field.

For Jio, that’s unacceptable, especially if it means loss of margins. In our Starlink story, we covered how Jio’s average revenue per user (ARPU — at ₹200+) is far lower than Starlink’s (₹7000+). But, Jio makes margins through its richer customers and institutional clients (like businesses, airports, and so on), who increase its ARPU. With lower costs, Starlink might be able to take away some of those customers.

Jio's next two counters are purely technical. For one, they say that congestion exists even in satellite internet. Satellites involve something called gateway stations which act like highways, beaming internet signals to Indian soil. While satellite operators can reuse frequencies, they can't reuse those gateway stations. When too many users in an area try to access satellite internet, gateways can clog.

Here’s another way to understand it: highways can be congested. Hence, it might make sense to implement some sort of congestion pricing to reduce the problem. In fact, that’s exactly what New York City did very recently.

Jio’s third argument is this: satellite internet requires millions of user terminals—dishes that consumers install on their rooftops. Without proper coordination, though, these terminals could interfere with each other and with land spectrum towers.

All of this is made worse by the fact that two particular frequency bands — called the ku (10-15 GHz) & ka (17-31 GHz) bands — are required strongly both by satellites and 5G towers on land. Land operators worry that their new investments in 5G may be spoiled because of this clash.

Two questions

Well, with these arguments, we had two questions in mind.

Firstly, why is Airtel opposing auctions? Jio’s case would actually heavily favor Airtel’s core business. Well, Airtel’s position is a little more nuanced. They maintain that they’ve had a consistent stance — they support administrative allocation overall, but recommend auctions in special cases, like when competing for urban customers. In fact, they’ve also lobbied against low costs for Starlink in India. It seems like they’re hedging their bets, but we can’t say for sure.

The second question: how does one address Jio’s counters? That’s where global parallels come in. The ITU has vastly improved coordination between satellite gateways. Additionally, other countries have instituted strong standards for satellite dishes so that they don’t interfere with each other.

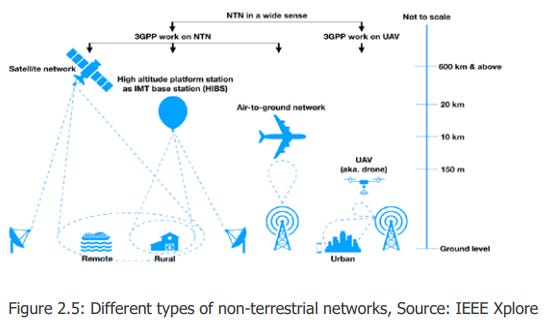

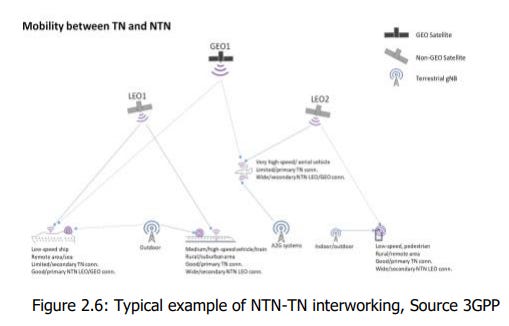

In other words, it is hard, but possible to manage these problems. Here’s a diagram from TRAI’s consultation paper on how land networks can network with satellites without interfering with each other:

Yet, there is one more reason why there’s still some hesitation around administrative allocation. And that has a bit to do with history.

The ghosts of scams past

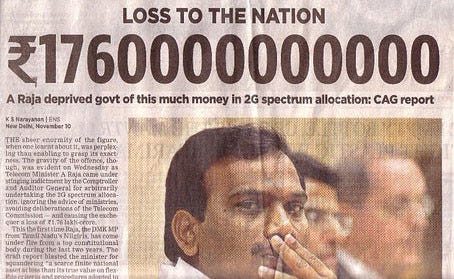

Let’s go back to 2008. Back then, Telecom Minister A. Raja allocated 122 mobile spectrum licenses on a "first-come, first-served" basis, in a market that exploded from 4 million to 350 million users. But the prices were way too low to justify that kind of market. The Comptroller and Auditor General estimated losses of ₹1.76 lakh crore, and the Supreme Court eventually canceled all the licenses in 2012.

Since then, administrative allocation has become a synonym for favoritism and corruption. Since then, the Supreme Court mandated auctions as the right method for spectrum allocation.

Now, we know that satellites are different from land spectrum, but every policy discussion is haunted by this scam. Critics reasonably ask: if administrative allocation was manipulated before, what's to prevent similar shenanigans in the satellite sector? Even if the argument for administrative allocation is theoretically sound, is the Indian government trustworthy enough to execute it efficiently without corruption?

That’s the historical baggage the Indian government has to deal with today. Which brings us to the DoT's current predicament.

A delicate balancing act

The DoT has demanded a rework of TRAI’s latest recommendations. It isn't rejecting administrative allocation outright—they certainly agree with TRAI on principle. But they're not entirely comfortable with the specifics.

For one, they find the pricing too generous for foreign companies. The proposed ₹3,500 per MHz annual minimum appears absurdly low to DoT officials. In their view, it doesn’t reflect the true value of the spectrum, and such low charges could encourage companies to hoard spectrum without using it efficiently. Or worse yet, turn into a cartel.

Then, the DoT has an issue with the ₹500 fee for urban customers. If you watched our story on rural India’s consumption trends, you’ll know that the urban-rural distinction can be blurry. That’s DoT’s stance — how do you define "urban" versus "rural" customers when satellite beams don't respect administrative boundaries? This could very well be an exploitable loophole. DoT’s view is that it might not be the best way to subsidize rural demand for satellite internet.

Another concern the DoT raised is a partial confirmation of Jio’s fears. To prevent congestion, it wants TRAI to fix limits for subscribers using a particular satellite system. While not the same as congestion pricing, this should have the same intended effect — disincentivize over-crowding.

DoT’s concern is also partly geopolitical. The Indian government considers telecom a strategic sector that cannot be dependent on foreign players, actively trying to reduce it. In May this year, DoT strengthened satellite communication rules to localize data and manufacturing, especially as many of the players entering our market are foreign.

At the same time, TRAI is trying to find a middle ground between both the DoT and the private sector. It’s worth noting that the Broadband India Forum — India’s private sector-representative body — doesn’t like a minimum charge on a per-MHz basis. They also highlighted the sheer difference in scale between land operators and satellites (which make up only 0.2% of all telecom revenue) — making such comparisons flawed.

Conclusion

Naturally, all of this has resulted in a further delay in policy. But, in the government’s view, this is a cost worth bearing for the government. They want satellite internet to help bridge the digital divide, but also not make it too easy for private players.

But even within private players, there’s very little consensus on what the future of Indian internet should be. It’s a multi-player Mexican standoff. We’ve also barely touched upon what this means for how business might be done in space.

This case is a maze of figuring out economic efficiency, equitable access, personal incentives and even geopolitics.

The Missing Middle in India’s Energy Story

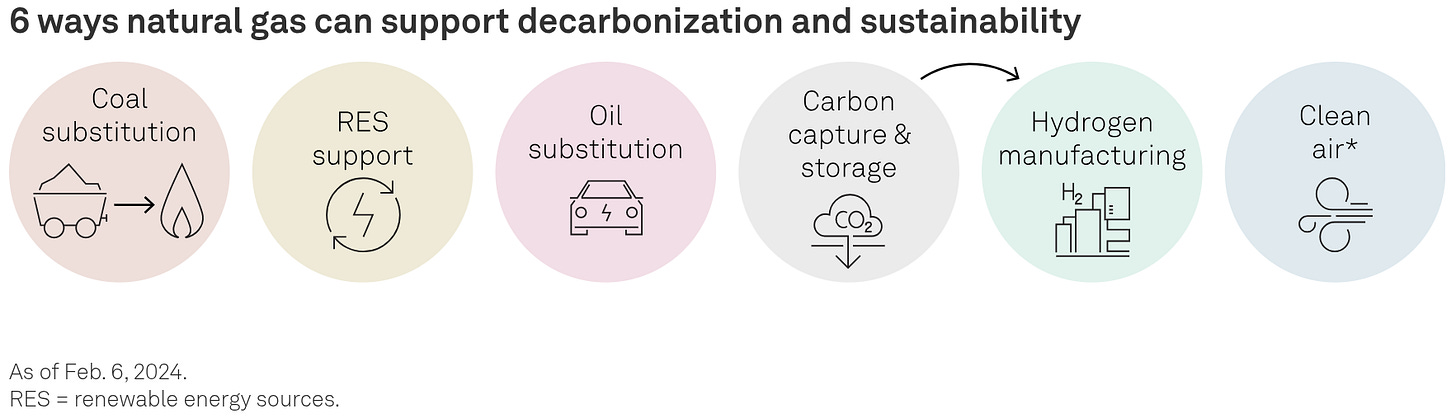

When countries talk about moving away from dirty fuels, the story usually follows the same script: first coal, then gas, then renewables. Gas acts as the bridge in this journey — the so-called “transition fuel.” It’s earned that title for a few good reasons.

First, it’s a cleaner substitute for coal. Burning gas produces about half the greenhouse gases per unit of electricity compared to coal, and without the soot, ash, or choking sulphur.

Second, its flexibility makes it a perfect match for the stop-start nature of renewables like solar and wind. Here’s why: clouds or calm weather can cause generation to drop, threatening grid stability — like what happened in Spain this April. In such cases, unlike coal plants, gas power plants can fire up in minutes, quickly restoring supply. Even in theory, running a grid entirely on renewables isn’t possible without a backup source like gas.

These strengths explain why, by 2050, gas is expected to be the only fossil fuel still increasing its share in the energy mix for countries like the US, China, and India — despite the global push toward renewables.

But here’s the odd part: India doesn’t really play this middle game.

Natural gas accounts for barely 5% of India’s electricity mix. We have 25 GW of gas-based power plants, yet they run at only about 10% capacity — practically idle. Meanwhile, coal still does the heavy lifting running at 80-90% capacity, and renewables are scaling up rapidly.

It’s as if India is trying to jump straight from coal to renewables, skipping gas entirely. That’s not how most of the world has done it. And it raises a sharp question: is this by design, or by necessity?

Before asking whether India needs gas in its transition, let’s first answer the obvious: why is gas failing here, when it seems to work everywhere else?

The strange case of India

On paper, India should have every reason to lean on natural gas. We’re choking on coal pollution, we import most of our oil, and renewables, while rising, still need a stable backup. Yet, in India, it’s stuck at the margins. And it’s happening for structural reasons.

The entire ecosystem — production, pricing, allocation, imports — makes gas an unviable choice which is scarce and costly. And those are the factors we’ll be tackling.

The problems in India’s gas production

India consumes around 60–65 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas every year. But we produce only about half of that. The rest has to be imported for one simple reason: India is just resource-poor in gas. We have plenty of coal, some oil, but gas reserves are small, scattered, and tricky to extract. Unlike Qatar or Russia, there isn’t a vast underground bounty waiting to be tapped. To give you context, we don’t even hold 1% of natural gas reserves that have been discovered yet.

But we could have had a better story. The discovery of the Krishna-Godavari (KG) basin by Reliance in the mid-2000s was hyped as a game-changing “gas jackpot” that would power industries. ONGC and Oil India were also supposed to step up with their fields. But despite making up 25% of India's total production, the basin’s reality has been pretty underwhelming. It didn’t deliver at scale, production targets have been repeatedly delayed, and domestic output is expected to be muted.

Even the gas we do produce doesn’t flow freely into the market. India follows a system called the Administered Pricing Mechanism (APM). In plain English: the government fixes prices for domestic gas and decides who gets priority. The logic is political and economic — fertilizer factories (because cheap urea keeps food prices in check) get first rights. Then comes city gas distribution (CNG for vehicles, cooking gas for households), which is visible to voters and tied to urban air quality. Only after that does the power sector get a look-in, and by then, there’s little left.

Even if India doubled its domestic production tomorrow, gas-fired power plants would still be left waiting.This leaves India with two options: either live with underutilized gas plants, or turn to imports. And that’s where the costs skyrocket.

Costly imports

If domestic gas is rationed and barely enough, imports should be the solution, right? After all, many countries run perfectly fine on imported natural gas. But here’s the catch: how you import gas matters.

Globally, there are two ways:

Pipelines – cheap, stable, and long-term.

LNG ships – flexible, but costly and volatile.

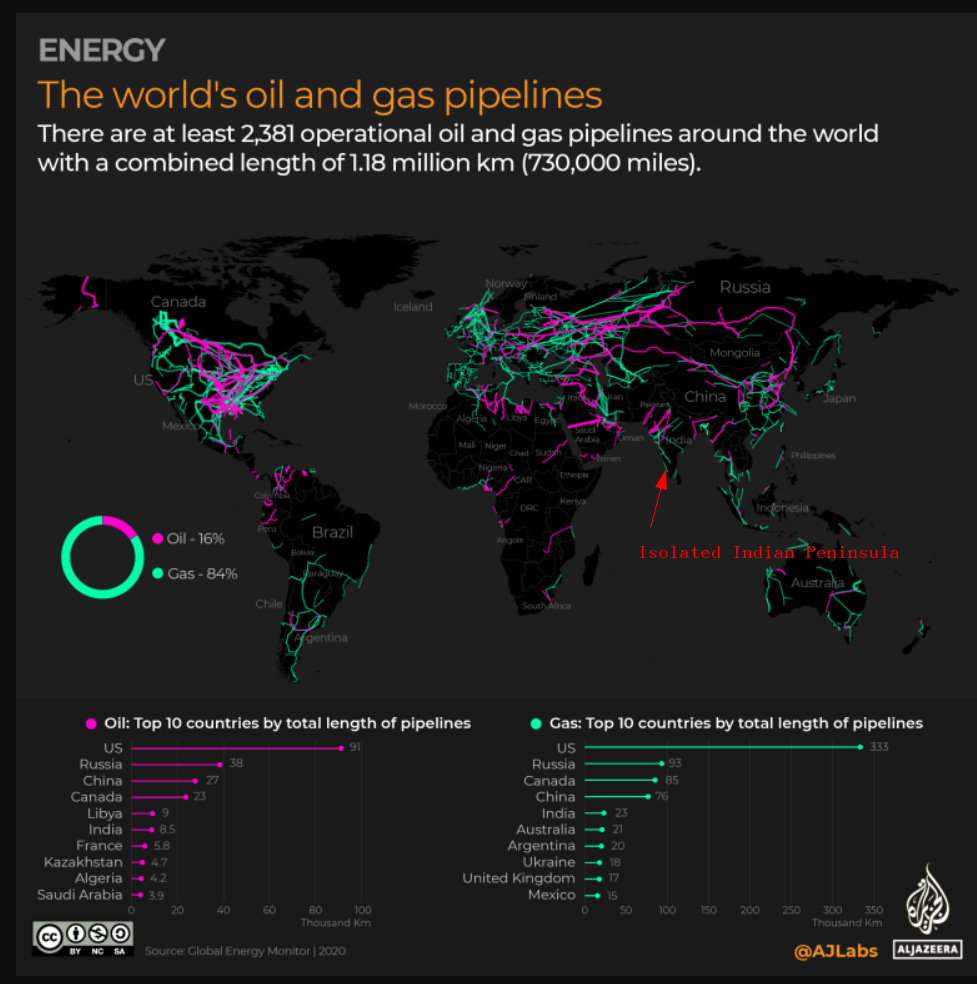

Most of the world leans heavily on pipelines. Europe has Russian pipelines (but they’re phasing out quickly), China gets pipeline gas from Central Asia and Russia, and so on. Pipelines are basically highways for gas: once built, they deliver fuel at a steady cost of $0.5–1 per unit.

India, though, has no international pipeline connections. The two big projects that were supposed to fix this — the Iran–Pakistan–India (IPI) pipeline and the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India (TAPI) pipeline — never materialized. Geopolitics, mistrust, and instability killed both.

So, India has no choice but to rely on LNG shipments, which is far less cost-efficient than pipelines. Here, gas is first cooled strongly to turn into liquid, which is transported in expensive cryogenic ships. Then, at terminals in Gujarat, Kerala, Maharashtra and so on, the liquid product is turned back into gas for our domestic pipelines. All of that adds $2–4 per unit.

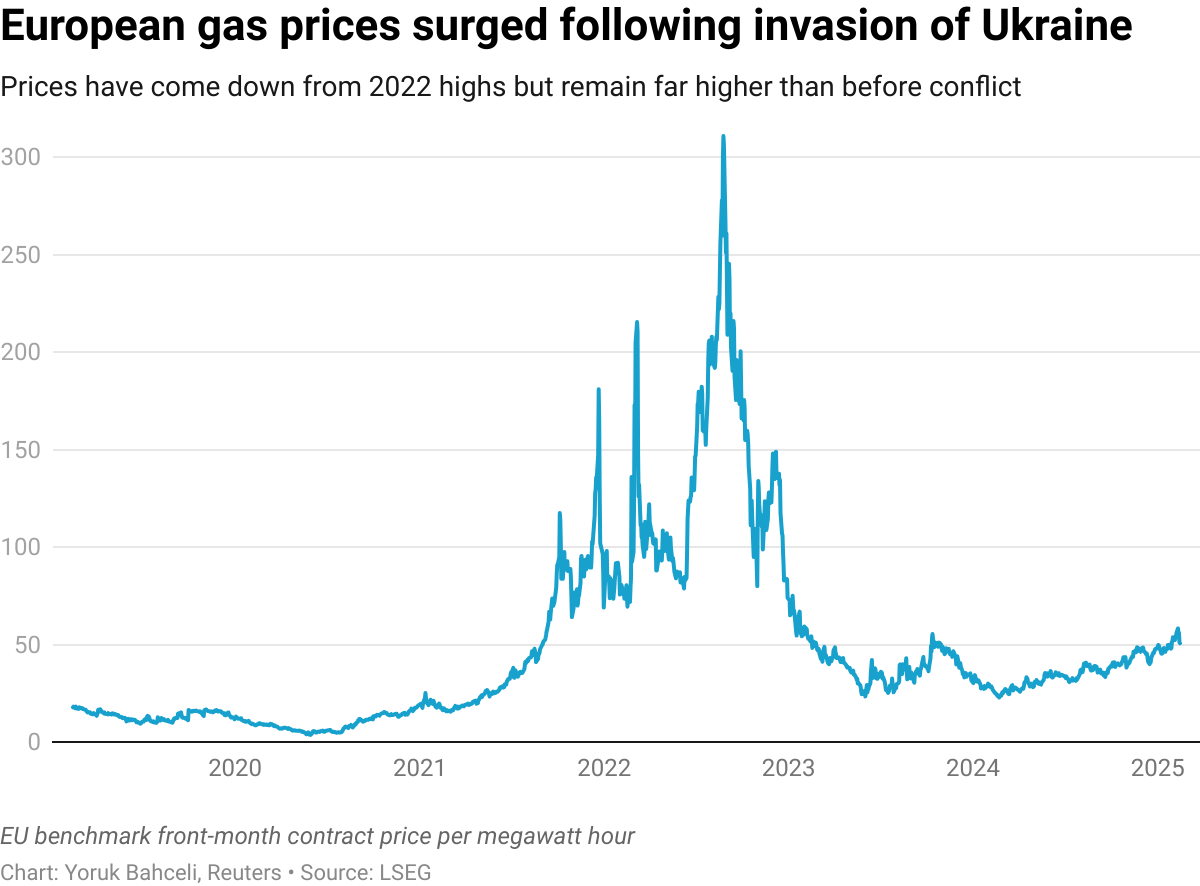

What makes this worse is that unlike pipelines, LNG is tied to global spot prices which are insanely volatile. In 2022, for instance, when Europe scrambled for gas in 2022 after Russia cut supplies, LNG prices shot up to record highs. Indian gas plants simply shut down — they couldn’t compete with coal or imported oil at those costs.

So, while importing coal or crude is relatively straightforward, importing gas is structurally more expensive for India. We don’t get the cheap, stable pipeline deals others enjoy; we get the volatile, expensive, seaborne stuff. This is why our gas power plants keep sitting idle — they take in gas which comes at highly unprofitable prices.

Gas loses steam to coal and oil

When you put gas side-by-side with coal and oil, its cost problem becomes obvious. But, there are other factors at play too.

Coal is messy. It pollutes and chokes cities, making it India’s single biggest carbon problem. But it’s also abundantly present within our borders. 75–80% of India’s coal use is met from local mines, and it powers over 70% of our electricity needs. Coal prices are also politically controlled. No matter how ugly, coal is a ready-made cheap crutch that policymakers can’t — or won’t — drop easily.

As we’ve covered before, crude oil is our Achilles heel, importing 85% of our needs. But it fuels transport and has no large-scale substitute. More importantly, India has built one of the world’s largest refining industries, which turns imported crude into petrol, diesel, jet fuel, and even exports. That turns crude into an economic (even geopolitical) benefit that we simply can’t do without.

That leaves gas in no-man’s land. While cleaner than coal and oil, it’s neither cheap nor essential. We import 50% of what we consume, but unlike oil, we don’t have to. We could just as easily run fertilizer plants on more subsidies or power plants on coal. And unlike coal, gas doesn’t have a strong domestic base. So it becomes the easiest fuel to sideline. Gas demand picks up when prices are low, but collapses when it spikes. Its supply can’t be politically controlled, so politicians don’t have incentives to back it.

The Big Question: Do We Even Need Gas?

So the real question isn’t why hasn’t India leaned on gas? The question is does India even need to?

One is naturally inclined to say yes — it’s too clean to be ignored. And as batteries are still only maturing, having a flexible standby fuel could smoothen the renewable journey. Even if it’s expensive, maybe it’s worth keeping some capacity alive for emergencies.

The other argument — which India seems to be implicitly following — is that gas is an expensive detour. The idea is it’s better to stick with coal as the dirty workhorse for some more time, while throwing full weight behind renewables and battery storage. If storage becomes cheap enough quickly, India could skip the gas stage entirely.

Either way, natural gas in India is not the star of the show (yet). It’s the understudy — useful in certain scenes, but never the lead.

Tidbits

Global city at Madurantakam

Tamil Nadu will develop a “global city” near Madurantakam, south of Chennai, with world-class infrastructure, housing, and commercial spaces. The project aims to attract global investors and ease pressure on Chennai by creating a new growth hub in the region.

Source: Times of IndiaSEBI clears Adani group

India’s market regulator SEBI dismissed Hindenburg Research’s 2023 claims that Adani Group manipulated stocks and hid related-party deals. SEBI said the transactions flagged were not connected entities under its rules. The allegations had triggered a $150 billion sell-off, but Adani shares have since recovered.

Source: ReutersCBI charges Anil Ambani, Rana Kapoor

India’s CBI has charged Anil Ambani and former Yes Bank CEO Rana Kapoor in an alleged ₹2,797 crore loan fraud. It said Yes Bank invested ₹5,000 crore in Ambani firms despite risks, with funds later siphoned off. Kapoor allegedly abused his role, causing losses to Yes Bank while benefiting Ambani firms and his family-linked companies.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉