India’s biggest carmakers switch gears — both up and down

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s biggest carmakers switch gears — both up and down

What India’s DPDP rules mean for the apps you use

India’s biggest carmakers switch gears — both up and down

Over the last few quarters, Maruti has been saying that something is off in the middle of the Indian economy. They kept repeating that the entry segment was not growing, that first-time buyers were missing, that small cars had basically stopped moving. We even did a Who Said What episode along those lines.

Here’s what RC Bhargava, the Chairman of Maruti Suzuki, said a while back:

“To buy a car costing 10 lakh plus, you normally would need to be in this household bracket of 12 lakh plus.“Car buying in India is largely restricted to this 12% of households. “How can you get high growth if 88% of the country are below levels of income where they cannot afford these cars costing 10 lakhs and above?”

This quote wasn’t a rant as much as it was a recognition of a key economic fact about India. That is, our lower-middle and middle-middle households, who normally power the first-car and small-car market, simply didn’t feel confident enough to stretch anymore. Let us rephrase it this way: the chairman of the country’s largest automaker says that the market is effectively resting on a very narrow top of the income pyramid. And sadly, there’s no other source of long-term demand.

You see, how we buy cars says a lot about our economy as a whole. Families only commit to buying them when they believe life over the next few years won’t surprise them in a bad way. Things like EMIs, fuel, school fees, rent, groceries — all of it must be stable enough before deciding to buy a car, which is already a depreciating asset. That’s why Maruti’s warnings about the entry segment felt heavy.

But this quarter, after two whole years, Maruti started to narrate a different, more optimistic story. Let’s dive into how Maruti Suzuki has performed this quarter — and how, conversely, Tata Motors hasn’t.

Maruti breathes again

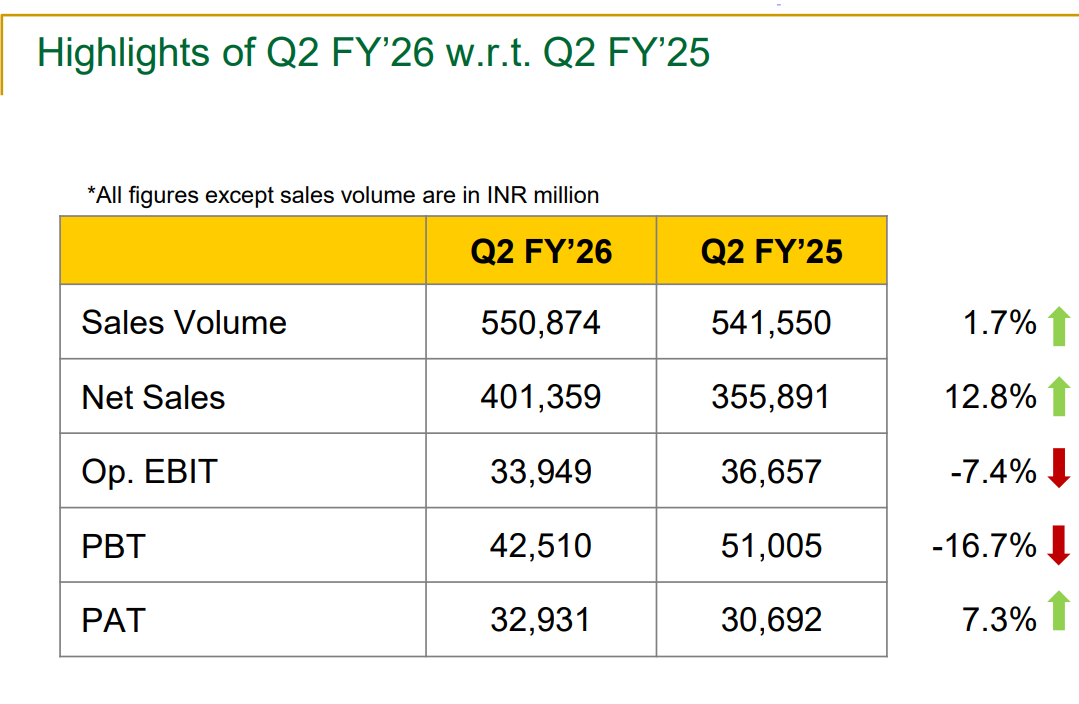

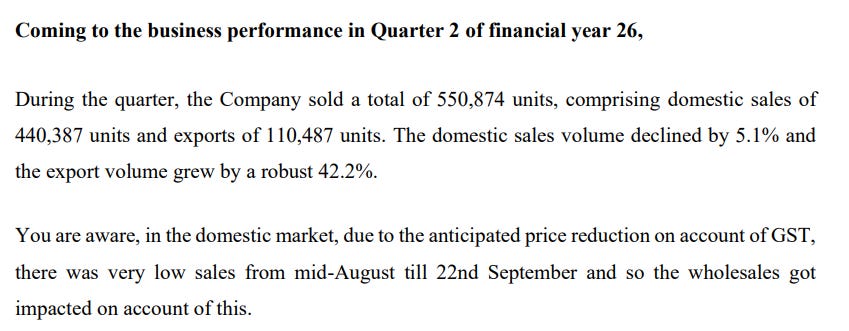

Maruti made ~₹40,000 crore in revenue this quarter, which is about a 13% increase from last year. But the number of cars they sold barely grew — volume went up by just 1.7% to 5.51 lakh units.

How did revenue grow so much when volumes didn’t? It turns out that the overall quarter still occupied a pretty sizable share of higher-priced models and strong exports, as opposed to small cars which yield lower realizations per car. Exports, for instance, jumped more than 42% to 1.10 lakh cars.

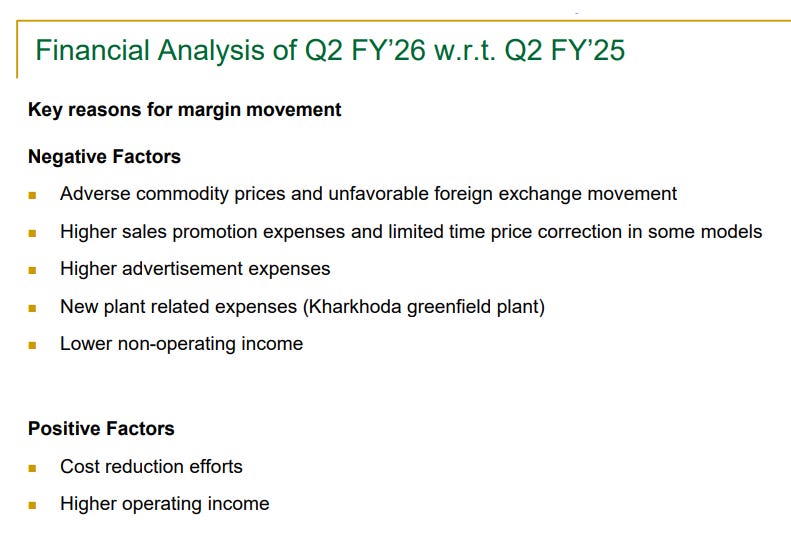

While revenue moves faster than volumes, profit didn’t rise at the same pace. Net profit was ₹3,293 crore, up only slightly from ₹3,069 crore last year. The reasons are manifold: higher advertising spend, costlier imported parts, and passing on a large chunk of the GST cut to customers instead of keeping it.

The real story, though, wasn’t in the profit-and-loss statement. It was in the retail numbers and the tone of the management call.

During the festive period, Maruti retailed around four lakh cars — a big number in itself — but the shock came from the breakdown of that number. About two and a half lakh of these were small cars. The very cars that India’s middle-income households buy, which had been shrinking for two years, suddenly produced their strongest festive season in recent memory. Here’s what Maruti said:

“And if we talk about retail sales, in festive period this year, we did about 400,000 units retail. And in the festive period, the previous year, retails were 211,000 units. And within this 400,000 units retail, about 250,000 units came from small cars, which had a growth of almost 100%”

A 100% jump in small-car retail is a big deal. And you could hear the relief in the way their management described the shift. For two years, the company kept reminding us that affordability at the lower end was squeezed, and many of our lower and middle-income earners hadn’t walked into a car showroom in a long while.

The GST cut helped here quite a bit. First, it caused a pause, because customers and dealers alike decided to wait for clarity. Then, as soon as the cut was announced on September 22nd, it created a sudden affordability jump. Cars that were just out of reach were now within arm’s length. Families who had been waiting for years suddenly found themselves in the “maybe yes” zone instead of “definitely not”.

Maruti has been just as optimistic about the growth of the industry as a whole — a stark contrast to their past gloom. Earlier this year, when asked about demand, they had said the industry would grow “a very modest one to two percent”.

But on the latest call, they said:

“But, at least, I think the total industry growth across all segments, we should see about 6% yearon-year on a sustainable basis.”

From 1–2% to 6%, with the word “sustainable growth” thrown in, this is no mere temporary speed boost. This is the company signalling that the base of the market feels different now.

And then came the line no one expected to hear from a company that usually refuses future margin guidance. When analysts asked about profitability, Maruti didn’t fall back on their usual “many factors make it difficult to predict” answer. Instead, they said that they’re keeping a 10% EBIT margin as their guiding light, and hope to reach it in time. If India’s largest carmaker is willing to state a target, it means they strongly believe demand is no longer fragile.

So when you put the numbers and the quotes together, Maruti’s quarter has been bright, and from the sound of it, they hope to continue to be upbeat in the coming quarters.

Tata Motors has some other problems

However, just as Maruti tells a story of recovery, Tata Motors somehow switched its gears down. It shows the opposite story playing out globally.

This was a messy quarter for Tata Motors, not necessarily because India is slowing, but because Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) — the part of the business that usually carries the group — ran into almost every possible headwind at once. This is also the first quarter after the commercial-vehicles business de-merged from the passenger-vehicle (PV) side, so the way the numbers show up on paper is slightly different. But that’s a sideshow to what’s happening with JLR.

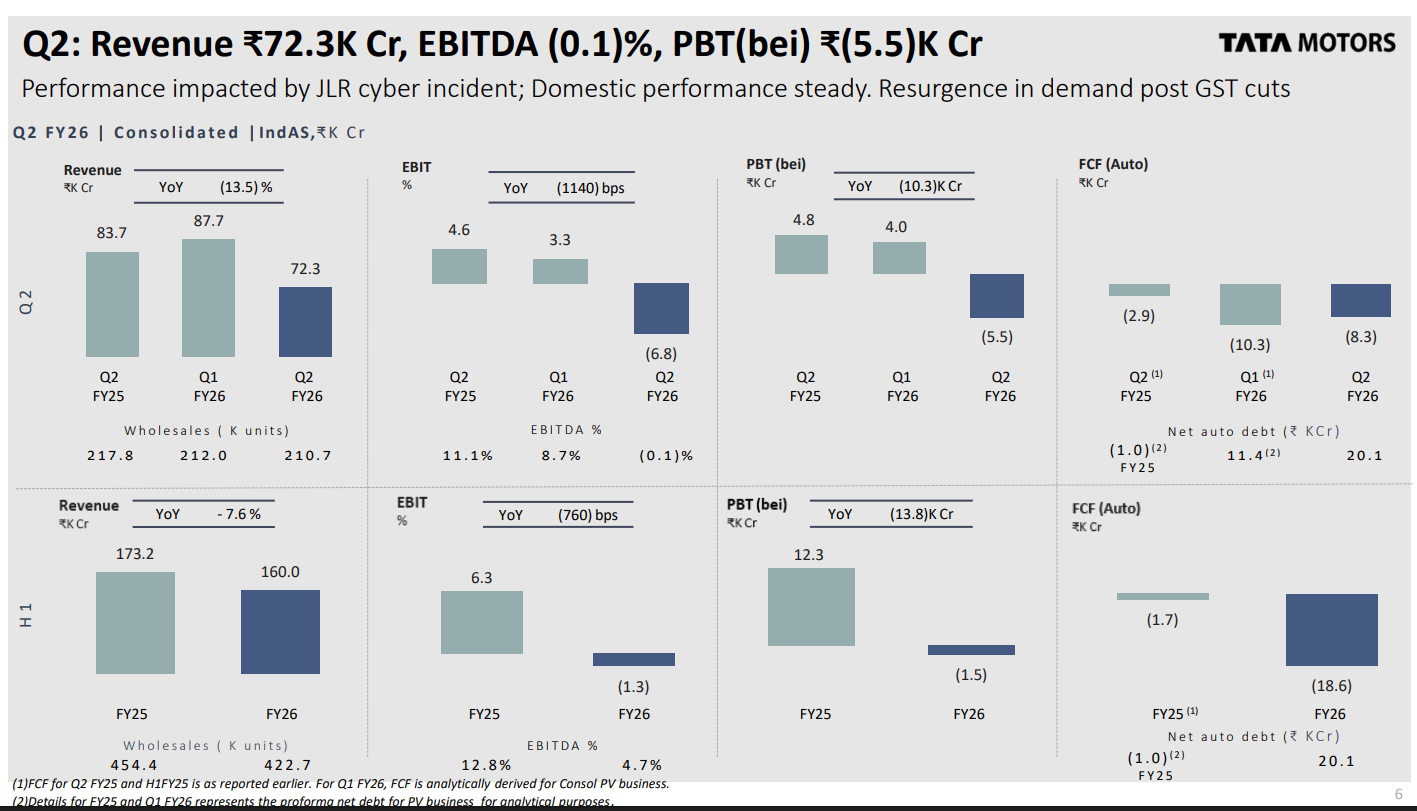

On the consolidated PV + JLR side, revenue is actually down about 13–14% year-on-year. The CFO says openly that the weakness at JLR was “only partially offset by 15% top line growth in the India business and the translation benefit in GBP–INR.” In other words, India is fine, but JLR was a massive drag.

The JLR story this quarter is one of operational disruption colliding with a weaker global luxury market. In September, JLR experienced a massive cyberattack which forced systems offline and brought almost all of its production to a halt. Volumes of key models like the Range Rover, Defender, and Discovery were 20–25% lower quarter-on-quarter.

At the same time, the luxury markets in China and Europe softened. To keep cars moving, JLR had to raise discounts, which jumped from 4.1% to 6.9%. Half of that hit wasn’t even from cars sold — it was from cars sitting in dealer inventory, because accounting rules force you to recognise the discount up front.

This is why the numbers look the way they do. The PV + JLR side ended the quarter with a PBT loss of around ₹5,500 crore, plus about ₹2,600 crore of exceptional costs linked to the cyber incident and voluntary separation programmes at JLR. Net auto debt also moved up to around ₹20,000 crore, largely because JLR had to absorb this shock.

And the part that really tells you where the mood is: guidance. A few months ago, JLR told investors they would do 5–7% EBIT margins and positive free cash flow for the year. On this call, they brought that down to 0–2% EBIT, and said full-year free cash flow will be deeply negative. When asked if the electric Range Rover or the new Jaguar timelines were shifting, they remained mum, saying: “Nothing to communicate at this point in time.”

Conclusion

In the end, what Maruti and Tata showed this quarter is that the auto market isn’t one single story — it’s two very different worlds sitting next to each other.

One is local, emotional, and tied to everyday life in India. That world finally loosened its shoulders. The people who had been putting off a car for years suddenly felt they could breathe again, and you could see it in the way small cars moved after the GST cut. When the bottom of the pyramid starts to stir like this, it usually means something inside the economy has quietly become less stressful — not perfect, not booming, just less tight than before.

The other, more global paradigm is running into headwinds. JLR’s year flipped from confident to cautious in a matter of months, not because the company forgot how to build cars, but because the broader environment turned cold. A cyber attack knocked them off balance, the luxury buyer grew more careful, and the EV timeline that was supposed to define the next decade suddenly became blurry.

So you’re left with a strange picture: India’s mass market is probably rediscovering its appetite, while the global premium market is pulling its foot off the pedal.

What India’s DPDP rules mean for the apps you use

8 years ago, India’s Supreme Court declared privacy a fundamental right. However, how this right was to be executed was still not clear, and we had to build a framework of rules to make it truly effective. It took until 2023 for us to pass the Digital Personal Data Protection — or DPDP — Act, which is the country’s first comprehensive data privacy law. And now, last week, the government finally released the line-by-line rules that make the Act operational.

The DPDP Act comes as India’s internet ecosystem — be it payments, e-commerce or food delivery — has exploded. UPI, for instance, processes 500 million transactions daily. At $60 billion worth of gross merchandise value, India has grown to become the world’s second-largest online shopping base. But with that comes concerns about how companies use (or misuse) customer data, or even cybercrimes, which have surged significantly in the past 4 years.

On that note, the new DPDP rules hope to shape both consumer and company behavior. We will be breaking down in simple terms how you should think about these rules, and how they impact India’s internet ecosystem.

Let’s dive in.

The user is king

The new rules divide India’s digital world into three roles: data principals (like you), data fiduciaries (which are companies handling your data), and consent managers — a new intermediary type that’s unique in the global context.

Let’s start with a data principal — the everyday internet user in India. The DPDP Rules now grant you, the principal, huge control over all your digital personal data. And this comes with many rights.

For one, you can now request access to your data, asking any company to tell you exactly what information they’ve collected and which third parties they’ve shared it with. Crucially, you also have the right to withdraw your consent at any time from an app, as well as ask a company to erase your data from their database. For instance, if you initially agreed to let a food delivery app use your location data, you can revoke that permission, and the company must stop processing it.

Some of these rights, however, are conditional based on whether they conflict with other statutory laws. For instance, DPDP rules cannot override certain SEBI rules that certify that immediate data erasure isn’t allowed. Nor does the DPDP require consent for “legitimate uses”, like law enforcement requests.

Companies on the hook

Now, these rights are enforced through a set of responsibilities on Indian companies.

The DPDP rules classify any organization that processes personal data in lieu of providing a service as a data fiduciary. So that effectively includes everyone from e-commerce platforms to banks to social media companies. And the law places lots of legal obligations on them.

Before collecting your data, companies must now obtain valid consent and provide a line-by-line description of what they’re collecting and why. Meaning, they have to tell you beforehand where and to whom your data is going, and they can’t collect more than what is necessary. But most importantly, consent has to be free, informed, and purpose-specific.

The DPDP Act also uses its own example of someone using a telemedicine app to make this point. If the app specifies two purposes which seem to require the same data, but are really independent of each other, a user should be able to select one without the other.

Here’s where it gets really interesting: what does it mean for companies that cross-sell products? Think about a superapp that offers a wallet service, gold loans, and insurance—all digitally. Ideally, each service requires separate consent — and you should be able to selectively withdraw consent from one service (like the loans) without losing access to the wallet.

Now, rules on cross-selling aren’t mentioned explicitly in the document. However, due to the DPDP Act, banks and NBFCs are already preparing themselves for an era when they can’t share data between their own subsidiaries that handle different products. This could potentially challenge the blanket “take it or leave it“ consent model that many platforms rely on.

The rules also mention the limitations of how long companies can retain data on their systems. They can’t hoard data indefinitely. Once the purpose is fulfilled or if you withdraw consent, the data must be deleted—unless the law requires retention for legal or compliance reasons. And the user must be informed 48 hours before their data is being deleted.

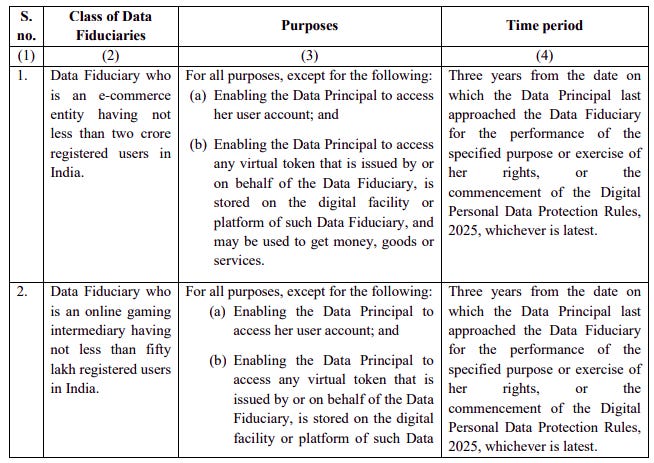

In fact, the law gets specific for certain types of companies. For instance, large platforms and social media firms with over 2 crore users in India, and online gaming companies with over 50 lakh users, must delete personal data if a user has been inactive for three years.

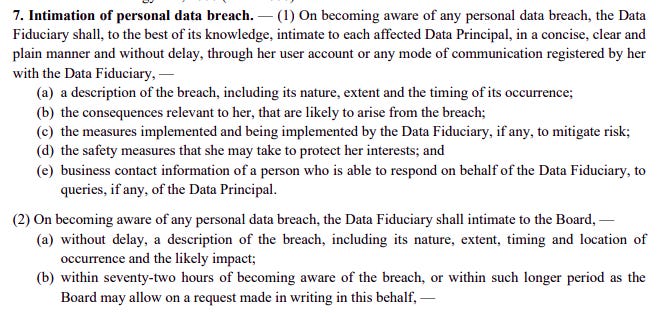

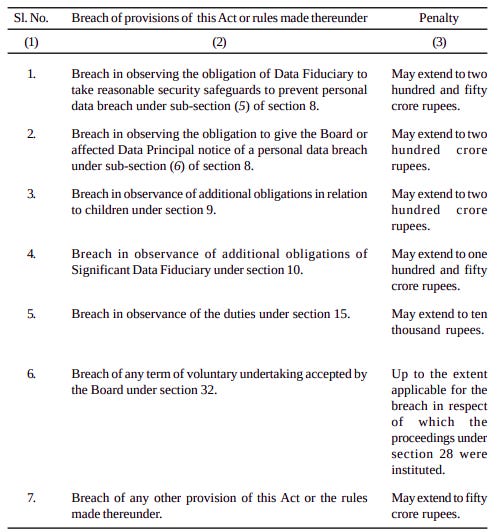

Obviously, the rules also make data security non-negotiable. Fiduciaries must implement reasonable security safeguards, like encryption, access controls, intrusion detection systems, and so on. And if a breach occurs anyway, they must notify both the central body that will enforce the DPDP Act (called the Data Protection Board), and the affected users, within 72 hours.

For companies processing large volumes of data or handling higher-risk activities, the government can designate them as “Significant Data Fiduciaries“. These entities face more requirements: like appointing a Data Protection Officer based in India, or conducting Data Protection Impact Assessments for risky processing activities.

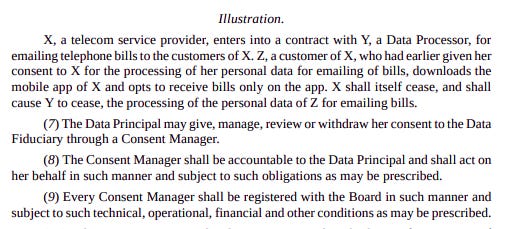

Now, the rules also identify the third-party vendors that data fiduciaries work with — they’re officially called data processors. However, while they’re recognized, the law doesn’t hold them directly liable for any rule breach — the fiduciary is held responsible. And if the principal withdraws their contract with the fiduciary, then the fiduciary also has to stop the processor from using the same data. If, for instance, a cloud storage provider mishandles your information, the company that hired them remains on the hook.

The data of children — which is anyone under the age of 18 — gets special treatment. Companies must obtain verifiable parental consent before processing kids’ data. More importantly, they’re flatly prohibited from tracking children’s behavior or serving them targeted ads, even with parental permission. Social media, gaming platforms, ed-tech apps—none can profile under-18 users for advertising.

A new middleman

To enforce the relationship between fiduciaries and principals, the DPDP framework has introduced another interesting stakeholder: consent managers. This manager is going to be a neutral third-party that acts as a single point of contact for individuals to manage their data consents with various apps.

Think of it as a consent dashboard. Instead of logging into each app or website to adjust permissions, you could use a consent manager platform to centrally control what you’ve agreed to. Give consent once, manage everything in one place, revoke permissions with a few clicks. Some consent manager tools already exist — like OneTrust, Usercentrics, Axeptio, and so on. But they’re not really India-specific, neither are they considered statutory bodies by the nations they’re based out of.

Using a consent manager is optional, not mandatory. You can still deal directly with each company for giving or revoking consent. But if a user routes their consent through a manager, that manager handles the record-keeping and verification on behalf of both user and company.

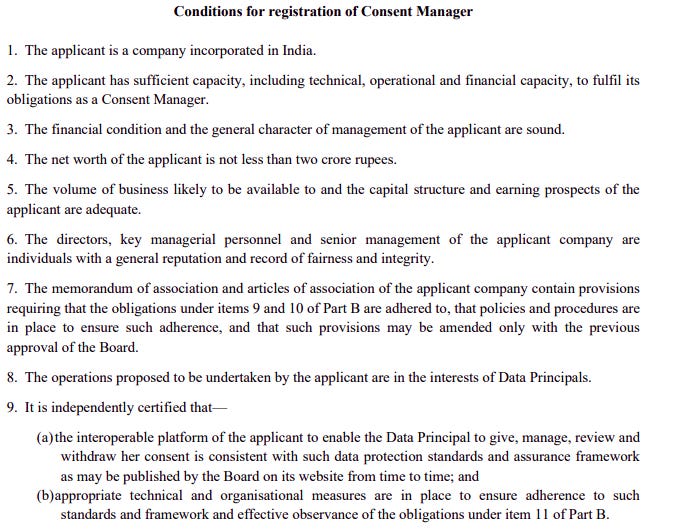

But it’s not easy to be a consent manager, as there are lots of conditions for their eligibility. An applicant — ideally a registered company — must register with the Data Protection Board. They must also have a minimum net worth of ₹2 crore. Moreover, the consent manager must be interoperable: meaning, their platform must be compatible across apps and services.

In fact, India has an analogy for consent managers in financial services — account aggregators, which are considered UPI for financial data. Their job is to transfer your financial data between two financial institutions without ever seeing the data themselves. And these aggregators are strongly subject to a central regulator (the RBI).

What this means for companies

Now, many of the rules under DPDP will only come into effect in the next 1.5 years. However, in both the short and medium-term, the compliance burden falls hardest on companies in sectors like fintech, e-commerce, ad-tech, social media, and gaming platforms. Especially those offering multiple services under one login.

The first, most immediate burden is building infrastructure around consent management, along with the help of a third-party that’s likely to register as a consent manager. Companies need systems to capture explicit, granular consent for each purpose. They may even have to create new consent forms at login to replace the complicated terms of service we are all so used to. Every consent must be logged with timestamps, metadata, and an easy withdrawal mechanism.

Secondly, companies will have to redraft their contracts with third-party vendors — like cloud providers, marketing analytics players, and so on — to whom they send any kind of user data for processing. Since fiduciaries remain directly liable for what their processors do with data, every third-party contract needs DPDP-compliant clauses, and a clear demarcation of who’s responsible for what. For instance, who pays penalties if there’s a breach?

Another urgency is how they respond to data breaches. With any breach requiring notification within 72 hours, companies need automated detection systems and templated workflows.

Now, some of these items seem to be quick fixes. However, their urgency comes from the fact that the penalties of not complying are eye-watering. Some of the instances of rule-breaking can cost a company as much as ₹200 crore.

Now, bigger companies have the muscle to absorb compliance costs. Many have been preparing since the Act passed in 2023, hiring privacy teams, deploying consent management software, conducting data audits.

But startups and MSMEs, that can’t afford to build a compliance vertical, are undeniably in a tougher spot. Building the infrastructure of consent tracking systems, security safeguards and grievance mechanisms takes resources they don’t have. Unless the government makes exemptions for smaller enterprises, MSMEs must find a way to comply.

Certain industries will have to deal with these rules more than others. In ad-tech, for instance, behavioral tracking without consent is off the table, and is outright banned for children even with consent. Even social media platforms may have to rewrite their consent form workflows to adapt to India. For fintech startups, which already are strongly regulated by the RBI, the DPDP rules may increase compliance costs. It’s still early days, but even within the digital realm, different industries will be hit in varying degrees.

Conclusion

India’s data privacy regime is now operational, and is finally beginning to move into the practical realm of how it’s actually executed. And it is an attempt to balance innovation and data protection across digital platforms.

However, how it is actually executed in the coming months is still up for debate. We have barely mentioned the grey areas that persist in this law. For instance, how big does a firm have to be to be classified a Significant Data Fiduciary? Or, while saying data must be deleted when the purpose is over, how does one define when the purpose is over? Or even something as simple as: does someone’s public YouTube account count as publicly-available data? What does this mean for Indian AI startups?

As with any law, the DPDP rules depend on how India’s judicial and financial infrastructure executes them. On paper, it looks like an Act that meets global standards for privacy. But how that translates on ground, for both privacy and innovation, is something we can only answer with time.

Tidbits

Pune Labour Commissioner summons TCS

The Pune Labour Commissioner has summoned TCS after IT union NITES filed complaints alleging abrupt terminations, forced resignations, and withheld dues. TCS plans to trim about 2% of its global workforce (~12,000 roles) through FY26, though the company insists reported higher layoff numbers are exaggerated.

Source: MoneycontrolIndia set for record wheat planting

Wheat acreage is expected to rise 5% to an all-time high, helped by improved soil moisture from 49% above-normal October rains and higher market prices. The expansion could boost output, cool domestic prices, and may even allow limited wheat flour exports. La Niña-driven colder winters are expected to aid yields.

Source: ReutersCentre proposes ₹30,000 crore UDAN revamp

The government has proposed ₹30,000 crore for an expanded UDAN regional air-connectivity scheme—₹18,000 crore for new airports and ₹12,000 crore for viability gap funding. The revamped version aims to add 120 new destinations and enable travel for 4 crore passengers over the next decade.

Source: BusinessLine

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Manie.

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

Introducing In The Money Podcast by Zerodha

In our first episode of the In The Money Podcast, we sit down with Tom Sosnoff, trader, entrepreneur, and one of the most influential voices in modern options trading. He talks about his early journey from the CBOE floor to building Thinkorswim and Tastytrade, his contrarian approach to risk, and why most traders misread probability and volatility. Tom also shares his take on Indian markets, the rise of retail participation, and the future of quantitative thinking for everyday traders.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉