India's alcohol market gets hit with a curveball

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

Also, a big thank you to everyone who tunes in, shares feedback, and spreads the word. We’ve just hit 200k subscribers on our YouTube channel! Couldn’t have done it without you 🙂

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The K-shaped trajectory of India’s alcohol market

Indian states navigate a tough balance sheet

The K-shaped trajectory of India’s alcohol market

Through the first half of this year, the liquor business seemed unstoppable. For the third consecutive half-yearly period, India had been the world’s fastest growing liquor market. Where international giants had seen their business tank in major markets worldwide, in India, the industry grew at a solid 7% year-on-year.

Last quarter, though, that momentum collided with serious headwinds: from poor weather to bureaucratic hurdles. But those headwinds meant different things for different companies. The industry saw itself bifurcate. Spirits companies, like United Spirits and Radico Khaitan, raked in record sums. The market for beer, meanwhile, contracted severely, with United Breweries reporting collapsing profits.

What happened? And what does it tell us about the industry? Well, let’s dive right in.

Three companies, three fates

Radico Khaitan had a wild quarter.

The company had spent the last year adding new capacity to its units in Rampur and Sitapur, which pulled down its supply slightly. Those units are now back in full form. With that, the company managed to increase its sales by an incredible 33.8% — with the output of its own factories up nearly 50% since last year.

This surge in sales meant that its fixed costs didn’t pinch nearly as much. Meanwhile, the company’s other costs were manageable as well, and a lot of those gains went straight to its bottomline. Its net profit, as a result, shot up to ₹138 crore — almost 70% over last year — marking a breakout quarter for the company.

United Spirits had a somewhat more, well, sober time — but it, too, held on to its growth momentum from earlier in the year. Year-on-year, its sales were up by 11.5%, to ₹3,170 crore, while its gross margin was up by almost 2% since last year. It also kept its other costs tight, allowing the company to expand its EBITDA by 32.5%. With some additional savings in tax and finance costs added to its pie, the company ultimately made a net profit of ₹472 crore — nearly 41% more than last year.

The beer market, however, was decidedly less upbeat.

United Breweries is just coming out of a terrible quarter. Its sales fell by 3% since last year, to ₹2,051 crore. Its gross margins contracted by a little more than 1% as well, partly because it outsourced some of its manufacturing. That’s not good, but it isn’t a disaster either. But on top of that, the company loaded on a barrage of other costs — it spent more on employees, on logistics, on growing its brand, on meeting its financing costs, and so on.

Together, these blew a hole through its bottom line. The company’s operating profit fell ~55% from its level last year. Its net profit, at just ₹47 crore, was down by ~64% year-on-year — that is, it made roughly one-third the money it did a year ago.

India’s alcohol market: a union of states

In India, state governments decide how they shall tax and regulate the liquor trade. That makes alcohol one of the last products for which India doesn’t behave like a single, unified market. If you’re running a pan-India liquor company, you’re basically dealing with the sort of legal complexity that only multi-national companies handle, with every state presenting a different legal regime.

Moreover, liquor is also deeply political in India. On the one hand, states see the business as a cash machine; while on the other, people have extremely strong feelings about liquor. This makes India’s many liquor policies distinctly schizophrenic. The laws you’re dealing with can change frequently — and by a lot.

The latest major disruption has come from Maharashtra. In June this year, the Maharashtra government effectively hiked the excise duty on liquor by 50%. The hike was capped, however, which meant that the brunt of this was borne by cheaper brands. While premium liquor increased by barely ~10% in price, cheap liquor suddenly went up by as much as ~80%.

That wasn’t all — because, at the same time, the government introduced a new category of liquor, called “Maharashtra Made Liquor”, for spirits made by manufacturers within the state. This would be taxed at far lower rates, just as the tax on outsiders went up. Effectively, if you were selling mid-range spirits in the state, your market was suddenly cut from right underneath you.

According to United Spirits’ estimates, the industry saw declines of 10-15% in their sales to Maharashtra. Their own mid-range spirits — like Royal Challenge and McDowell’s — were hit by a ~35% hike in prices. To stay competitive, the company was forced to restructure its supply chain.

That said, some categories like beer and wine were exempt from these higher taxes. And they benefited from a lot of the business that spirits companies lost. United Breweries, for instance, saw double digit growth in the state, as the rest of the industry was coping with the damage.

That said, United Breweries was at the receiving end of similar measures in other states. At its investor call, it noted that some states — like Karnataka and Telangana — had drastically hiked their taxes on beer in recent years. If they hoped that this would increase revenues, however, that plan back-fired. Instead, these turned out to be lose-lose moves. These higher prices caused consumption to crater, pulling down the government’s revenue as well.

For all this volatility, however, there’s a silver lining. Occasionally, states liberalise their policies on liquor, which can open up huge new possibilities for liquor companies.

Take the example of Andhra Pradesh. Back in 2019, the Andhra government promised a complete prohibition on liquor. While it didn’t quite get there, it placed severe restrictions on its trade. The government took on the exclusive privilege of retailing premium liquor, and reduced the number of liquor shops by roughly a third. In practice, once this policy took hold, the government stopped buying well-known liquor brands from reputed companies, and allowed obscure brands to cash in.

But then, the ruling party changed. And with it changed the government’s stance on alcohol. The new government argued that these restrictive liquor policies had cost the exchequer nearly ₹19,000 crores in lost revenue. In its place, it brought in a new excise policy, letting private entities to retail liquor once again.

The Andhra market — by some estimates a tenth of India’s liquor market — was suddenly open. If you were in the right place, and could execute quickly, you could grow rapidly.

That’s what Radico just did. In the first half of last year, it held 10% of the Andhra liquor market. But as the state opened up, the company quickly scaled up its distribution and made sure it was available through the state. In a single year, its market share jumped up to 30%. It is now the biggest player there.

Premiumisation

As we’ve written before, we’re currently in the midst of a premiumisation wave across the alcohol industry. Many companies appear to have realised that the lower-end volume game simply isn’t worth it — there’s too much competition, and the low margins are barely enough to make up for all the volatility and red tape you face. India has a growing cohort of people that want to drink better liquor, rather than more of it, and the entire market is betting on them.

To us, that looks like a good bet. Just take the results of United Breweries — they might have had a nightmare quarter overall, but their premium portfolio was a distinct silver lining, with volumes growing 17% year-on-year. If you want to survive the tremendous uncertainty of the liquor business, it seems, look for customers that’ll pay you well for your troubles.

Both United Spirits and Radico Khaitan, in fact, are quickly turning themselves into exclusively premium brands. Almost 70% of Radico Khaitan’s sales, now, are in the “premium and above” category. United Spirits has gone even further, with roughly ~90% of their sales coming from premium liquor and better.

If anything, these companies are setting their sights even higher, to what they call the “luxury‘ segment. If consumers take to such a brand — and that’s a big “if” — companies gain considerable pricing power, beside a lot of prestige. A single bottle of Radico’s Rampur whiskey, for instance, frequently sells for well above ₹10,000. Around a tenth of Radico’s revenue now comes from its luxury segment. United Spirits, too, is doubling down on luxury brands like Godawan and Johnnie Walker.

These companies are also on the look-out for niches to exploit within the premium segment. Take white spirits, like vodka. Traditionally, these weren’t very popular with older male drinkers. In fact, they accounted for less than 2% of the market just three years back. But now, there’s a demographic shift in play. Women and young people are showing much more interest in alcohol, and they prefer white spirits — which have rapidly climbed to 4% of the market. Radico has been lying in wait for this very moment. With dominant brands like Magic Moments in its portfolio, it runs 85% of India’s white spirits business. As this shift has played out, most of the new demand has gone straight to its top-line.

The rain as a wet blanket

The rains this year, as you’ve probably seen around you, have been relentless. They were unusually heavy, and more importantly, carried on until well after the monsoon usually ends.

In a consumer-oriented business, that can be a big deal. The rains have probably forced you to change your own plans at some point over the last few months, and that’s also true of the rest of the country. Rains can change how an economy behaves, and what people are willing and able to consume.

Beverages, it turns out, suffer massively in times of wet weather. People usually get themselves a drink when they step out of their homes — for instance, during social gatherings, or when they go out for a meal. Rains, by making it harder for people to head out, can seriously hurt a beverages business. Both PepsiCo and Coca Cola, for instance, have reported a decline in volumes due to the weather.

That’s also true of the alcoholic beverages market.

This year, United Breweries saw the rains wreck its business completely. In markets where it rained the most, the company says, beer sales dropped by as much as 40%. Collectively, these areas made up roughly one-third of its market. Worse still, the company’s own units were in the same areas, and three of them were flooded as well — and had to be shut down for maintenance. That is, in the areas that took the worst hit of the monsoon, the company simultaneously saw demand dry up, and their operations fall apart.

The bottomline

So, how should you see the industry’s split fortunes this quarter?

Well parts of this business run like any other — you have to anticipate what customers want, make quality products, and sell relentlessly. But there are other parts that are much more unpredictable. You need to survive fragmented regulations and shifting political currents. You have to learn how to live with things like bad weather.

The industry seems to have hit on one answer that seems to work: the higher you climb up the price ladder, the more stable things seem to get. The mass market for liquor is shaky and brutal; if anything, it’s premium customers that are easier to please.

Is this a guarantee of renewed success? We don’t think so. There are just too many factors at play, most of them too whimsical to build any concrete ideas around. For all we know, the next time we cover this sector, the fates of these three companies may have inverted completely.

Indian states navigate a tough balance sheet

Recently, PRS Legislative Research released its report on the state of state finances across India.

It’s a really interesting report, not just because of the numbers, but what the numbers reveal about how financial power and risk are distributed across the Indian government machinery. The RBI also does a yearly breakdown that we covered last year. And overall, the report depicts a picture of some concern — not very different from last year.

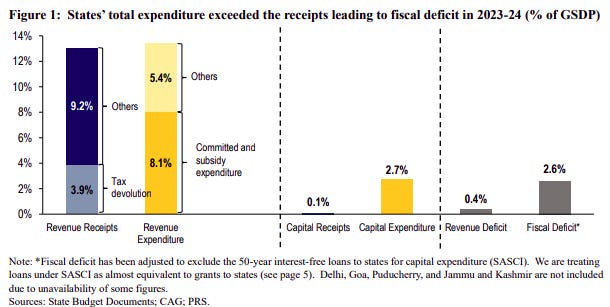

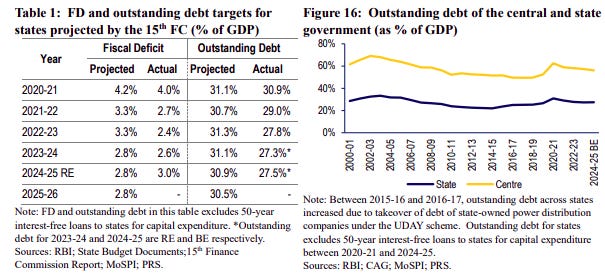

The finances of many states are under considerable strain. The aggregate fiscal deficit went up from 2.6% of Gross State Domestic Product (or GSDP) in 2023-24 to ~3% by 2024-25—precisely at the limit set by the Finance Commission. This deficit means they have had little headroom to spend on big-ticket items. Now, this doesn’t mean the country is in big trouble. But within this statistic lie many nuances about the trade-offs individual states face, who bears the risks of what and how (and why) some states do worse than others.

And that’s what this story is about: trade-offs that are present in any and every economic strategy, no matter how good the strategy may be.

So let’s dive in.

A squeeze on the long-term

The headline finding of the report is this: a lot of what states spend money on isn’t productive investments like factories and roads (or capital expenditure), but day-to-day operations (or revenue expenditure).

In 2023-24, states spent 62% of their revenue receipts on just four categories: salaries (26%), pensions (13%), interest payments (13%), and subsidies (9%). Some states spent more than others — at the extreme end, Punjab spent 107% of its revenue receipts on these items alone. By the time they’re done spending on the basics, they might even have to go into debt. The ratio for neighbouring Haryana, meanwhile, was 71%.

In fact, on aggregate, states recorded a revenue deficit of 0.4% of GSDP in 2023-24. What this deficit means is that they didn’t generate enough revenue to fund day-to-day operations like salaries and pensions. Some states had to borrow from outside to make this shortfall up.

These are items where there is absolutely no room to budge. Many of these, like salaries and pensions, are contractual obligations that if not paid on time and in full, will certainly lead to a riot. Interest payments on existing debt are non-negotiable.

Then, many of these items are politically sensitive — like subsidies for power and farming. If anything, more items are being added to the equation. Like unconditional cash transfers to women, for which 12 states budgeted roughly ₹1,68,000 crore combined (or 0.5% of India’s GDP). Six of these states had already recorded revenue deficits even before these transfers.

So, the only flexible component — the only place states can hold back on spending — is long-term productive capex on infrastructure or industry. Think about that for a second: money-starved states are choking their sole growth engine just to meet daily ends. Between 2015-16 and 2023-24, while revenue expenditure underspending by states was just 7%, capex fell short by 20%.

The revenue generation challenge

Now, you might have had another question in the midst of this. Why can’t states simply generate more revenue?

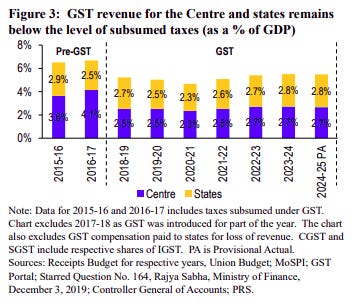

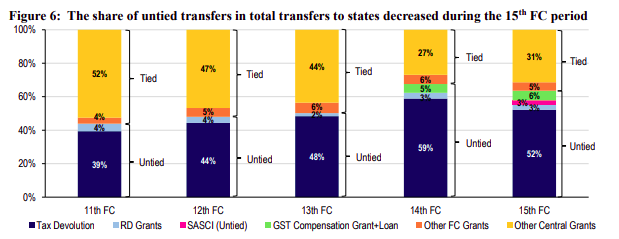

See, unlike the Centre, states can’t really print their own money, so that’s out of the question. They have to raise funds by other means — primarily taxes, which is their biggest source of receipts. And for states, the biggest tax receipt is the State GST (or SGST) that subsumed individual state taxes, and now accounts for 44% of states’ own-tax revenue.

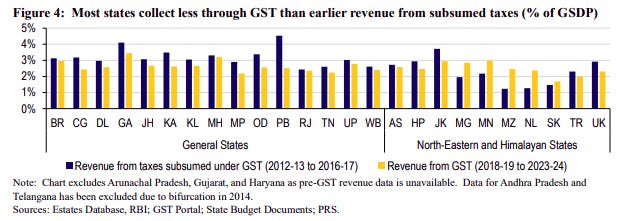

However, since the introduction of the GST system, SGST has consistently fallen short. Aggregate revenue of all taxes — both Central and state — subsumed under GST declined from 6.5% of India’s GDP in 2015-16 to 5.5% in 2023-24 — significantly below the 15th Finance Commission’s medium-term target of 7%. Overall, SGST as a share of India’s GDP has fallen compared to pre-GST tax revenue.

Now, this isn’t necessarily just a bad thing, but it represents a trade-off. GST is a simple, unified tax system that has increased ease of business and the inter-state movement of goods. However, it has come at the cost of lower state tax revenue, and more importantly, lesser autonomy in how individual states can set economic policy. For a breakdown on how India has tried to manage this dilemma, we recommend reading our GST primer.

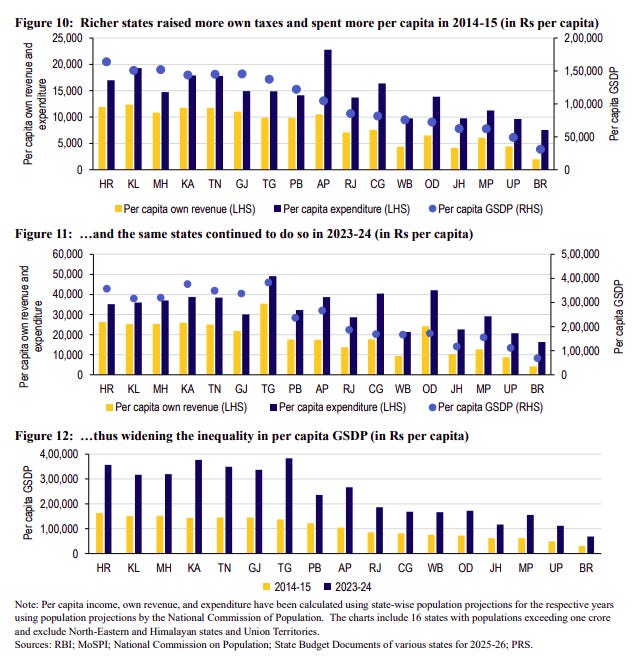

Some states perform worse than others, which, in turn, increases inter-state inequality. States with higher per capita GDP generate more revenue per capita, and therefore more taxes. These are the only states that have enough money to pursue long-term capital-heavy projects.

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle. Higher initial income leads to greater investment capacity, which drives further growth, widening the gap with poorer states. While states like Haryana, Kerala, and Maharashtra invest substantially more per capita, others like Bihar and UP do much less.

Between 2015-16 and 2023-24, states on average collected 10% less revenue than what they planned for in their budget. States like Manipur (27% shortfall), Telangana (21%), and Andhra Pradesh (20%) saw particularly large gaps between projected and actual receipts. Non-tax revenue, at just an average of 8% of receipts across states, offers limited scope for augmentation.

Increased dependence on the Centre

Now, the Centre has stepped in to make up for this shortfall — especially when it comes to capex.

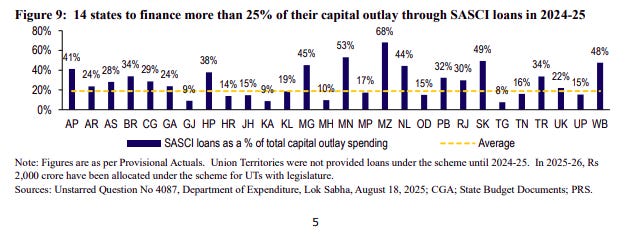

For instance, the Scheme for Special Assistance to States for Capital Investment — or SASCI — provides 50-year interest-free loans to states for capex. Allocations grew from ₹12,000 crore in 2020-21 to an estimated ₹1,50,000 crore in 2025-26. States now fund 19% of their capital outlay through SASCI, compared to just 2.9% in 2020-21.

However, this might create a situation where the states become too dependent on central transfers. The conditional component of SASCI, for instance, has expanded dramatically. In 2022-23, 80% of SASCI funds were unconditional. By 2025-26, only 38% remains unconditional, with the majority tied to specific schemes. In fact, for north-eastern Indian states this dependence is even more pronounced — 68% of their revenue receipts are Central aid.

Again, this isn’t entirely just bad. But it’s a trade-off between what states can do themselves, and what they’re ordered to do from above. And so far, this trade-off is not being managed well, since states end up overspending.

The debt dimension

So, if you can’t raise revenue from tax and non-tax sources, and your dependence on the Centre becomes heavier, what option do you have left? Borrowing.

And over the last few years, states have increasingly turned to raising debt. Outstanding debt reached 27.5% of GDP as of March 2025, above the 20% FRBM Review Committee target. And while debt levels are decreasing gradually, there’s still a long way to go.

However, that’s just the aggregate debt level. The divergences between the debt levels of individual states are even more stark. Only three states — Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Odisha — meet the recommended 20% debt ceiling. Punjab (46%), Himachal Pradesh (44%), and Arunachal Pradesh (42%) carry debt burdens more than double that ceiling.

But this is just direct debt that you can see on the balance sheet. Beyond this, states also assume responsibility for the debts borne by inefficiently-run state PSUs. As of March 2024, guarantees across 27 states amounted to 4.4% of GSDP. Telangana (15.1%), Andhra Pradesh (10.9%), Sikkim (9.5%), Rajasthan (7.3%), and Uttar Pradesh (6.4%) have particularly high exposure. Without the state government’s guarantee, these PSUs don’t look very credit-worthy.

Almost half these guarantees come from the power sector alone. And the reason isn’t hard to guess — state-owned power discoms operate with little financial discipline, registering aggregate losses of ₹34,453 crore in 2023-24. Their outstanding debt as of March 2024 stood at ₹7,42,461 crore (or 2.7% of the average GSDP).

Often, these discoms default on their debts as they have no reserves to pay loans back. In that case, state governments must honor the guarantees taken on the behalf of discoms. In a way, this is an unplanned emergency they need to account for that wasn’t there earlier on their books.

Systemic implications

Put together, the PRS report’s findings show the workings of India’s federal fiscal architecture. This strategy prioritizes centralizing power over giving Indian states their own autonomy. But every strategy prioritizes some things over others. And this would have been fine if the resulting trade-offs were well-managed.

However, what’s happening instead is worrying. States don’t have enough sources to generate revenue. All the while, they’re constantly overspending on their regular operations for reasons both within and beyond their control. As a result, they take on more and more debt, limiting how much they can spend on real, productive investments. Moreover, while some states are doing very well, others are hurting far more.

None of this means we’re doomed — in fact, this framework does have some benefits. Through GST, the streamlining of taxes between states has made the movement of goods and logistics within India far smoother. It also centralizes decision-making related to finances, which might be more efficient in some cases.

However, this architecture has tradeoffs. And without addressing those tradeoffs and imbalances adequately, states will have little choice but to keep fighting their battles alone, even taking a toll on India’s economic growth as a whole.

Tidbits

China’s exports fell 1.1% in October — the steepest drop since February — as the rush to ship goods ahead of new U.S. tariffs faded and American demand weakened sharply.

Shipments to the U.S. plunged over 25%, underscoring China’s heavy reliance on U.S. consumers even as it tries to boost trade with Europe and Southeast Asia.

Source: ReutersIndia is exploring ways to build more large, world-class banks, including fresh rounds of mergers among state-owned lenders, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said.

Source: Reuters

Toyota, Honda, and Suzuki are investing over $11 billion to expand production and exports from India, turning it into a key manufacturing hub as they reduce reliance on China.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Manie

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉