Indian hotels: a quarter of repairs

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How did Indian hotels do this quarter?

How do companies really allocate their capital?

How did Indian hotels do this quarter?

Today, we will be looking at the latest quarterly results of three hotel companies — Indian Hotels, Chalet Hotels, and Lemon Tree Hotels.

July through September is usually the weakest quarter for Indian hoteliers. The monsoon months blunt leisure travel, corporates cut back on conferences, weddings thin out, and demand settles into a seasonal trough just before the big winter spike. The headline numbers look fine. But dig in, and you’ll see each company dealing with familiar seasonal pressures in different ways.

Before we get into the details, it’s worth understanding how these companies actually make money — not all hotel businesses work the same way. For a more detailed breakdown, we recommend reading our coverage of the Q4 FY25 results.

First, the asset-heavy model. You own the building, you run the hotel, you keep all the revenue, but also bear all the costs. Chalet, for instance, works this way. It owns its properties outright, which means high capital requirements but also full control over operations and pricing. Chalet adds another layer by owning commercial office space alongside its hotels, creating a diversified real estate play.

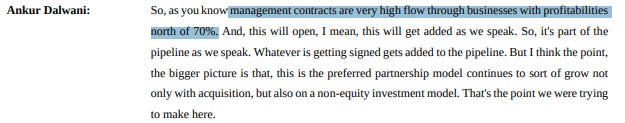

Second, the asset-light model. You don’t own the building but simply manage the hotel for a fee. The capital requirement is low, margins are high, but your revenue base is smaller.

IHCL and Lemon Tree both started as owner-operators, but are moving toward becoming asset-light. IHCL still owns iconic properties like Taj Mahal Palace in Mumbai, but its recent growth has come through management contracts—collecting fees for running hotels owned by others. Lemon Tree is doing the same, signing franchise and management deals that let other people’s capital fund expansion, while Lemon Tree provides the brand and operational know-how.

Now, let’s dive into the numbers.

The Indian Hotels Company Ltd. (IHCL)

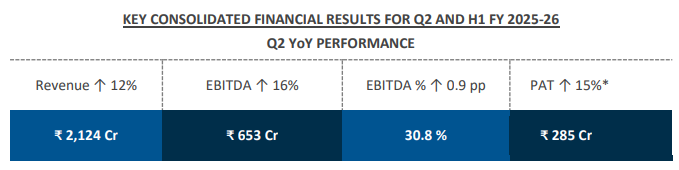

On a consolidated basis, IHCL posted a little over ₹2,124 crore, up 12% year-on-year. EBITDA grew to ₹653 crore, pushing margins to 30.8%. RevPAR — which is how much money a hotel makes per room per night — grew around 9% in the first half, driven by price increases rather than occupancy rates. From the top, these numbers look healthy.

However, the standalone core business, which contains the prestigious Taj and Vivanta brands, grew quite modestly. For a company that had been reporting rapid growth quarters during the upswing, this near-flat print stood out a little sorely.

However, there may be a valid reason for this. IHCL chose Q2 to renovate its flagship properties. At Taj Palace Delhi, for instance, around 150 rooms went offline. The President in Mumbai had 76 rooms under work. Parts of Taj Mahal Palace, Fort Aguada in Goa, and Taj Bengal in Kolkata, were all being renovated. Renovation doesn’t just shut rooms—it dampens rates on surrounding floors, curtails banquet activity, and disrupts food catering operations.

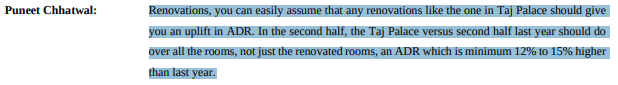

In fact, one could view these renovations as investing in the future. Management expects these repairs to boost Average Daily Rates (ADR) — or the average price a hotel charges for each occupied room per night — in upgraded properties. Taj Palace, for instance, could potentially see a 12-15% increase in ADR in the second half of the year.

What saved the consolidated picture were the smaller non-flagship brands. Ginger delivered a stronger quarter, while TajSATS continued its steady climb, and amã Stays and Tree of Life expanded. International hotels, particularly in the US and UK, reported double-digit growth. These made the business look much healthier than what the flagship Taj hotels alone might suggest.

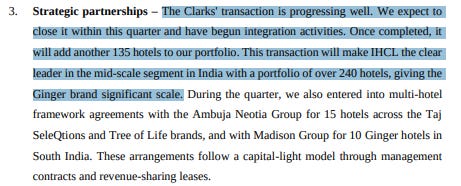

IHCL is also continuing to expand. It has signed 46 new hotels in the first half, taking its portfolio to 570 properties with 302 in the pipeline. Their acquisition of Clarks Hotels, they hope, will expand their footprint in the more economical hotel segment.

IHCL’s move toward the asset-light model of management contracts is paying off, too. Ideally, the higher margins from this model should reflect even more in the coming quarters.

Chalet Hotels

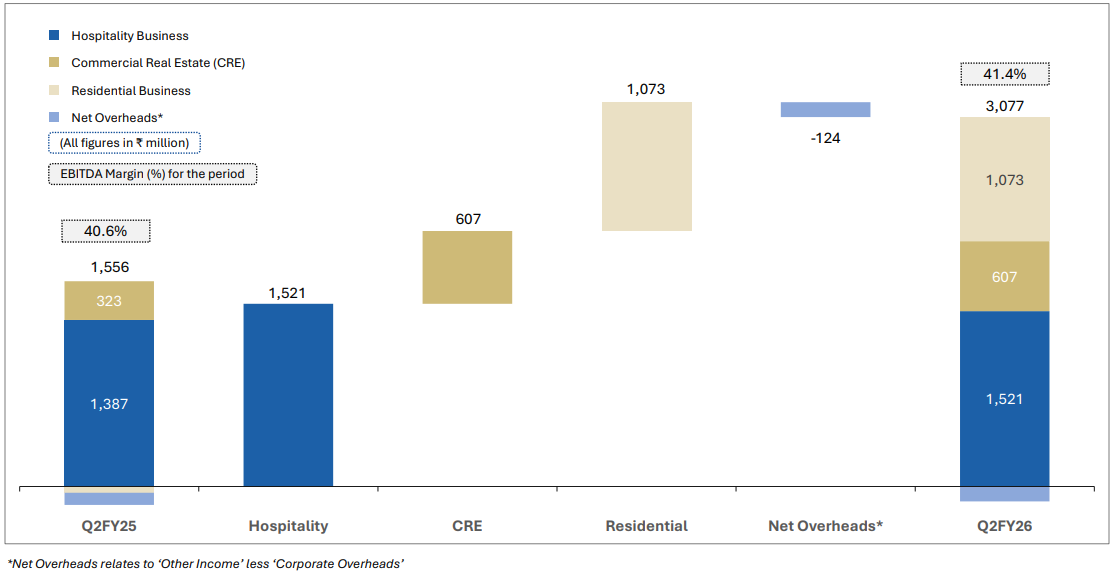

Excluding a one-time residential apartments sale, Chalet’s core revenue grew 20% to ₹460 crore. The consolidated EBITDA margin hovered around a massive ~41%. ADR climbed 16% to ₹12,170—the sharpest rise among the three companies.

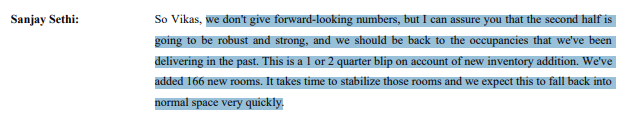

Now, the occupancy dropped to 67%, down seven percentage points, because 166 new rooms at the Westin Powai property were still filling up. But, the company expects a strong second half with a return to historical occupancy levels, viewing the recent dip as just temporary.

If IHCL is a story of renovations meeting an asset-light model, Chalet is a story of ownership hiding behind legacy international brands.

Chalet owns some of India’s most recognisable hotels like the JW Marriott Sahar, The Westin Powai Lake, and so on, but none carry Chalet’s name. They’re actually all run by Marriott or Accor. The buildings, land, rooms, banquet halls and cash, however, belong entirely to Chalet. Chalet simply borrows the Marriott brand name and pays them a royalty fee.

Chalet puts up the money, takes the debt, maintains the building, and carries the risk. The Marriott name, on its part, brings the brand, the booking system, the loyalty programme and the corporate tie-ups. Chalet keeps most of the revenue and profit.

In fact, Chalet uses the exact playbook with the Taj brand name with a property near the Delhi airport. They expect that many of the customers here won’t be wedding guests or conference attendees, but travellers (potentially for business) who may stay for a very short duration. So, this hotel might have a quick turnover of guests, but also expects very high occupancies—possibly over 100%.

Chalet is also expanding aggressively, with plans to spend ₹2,500 crore over the next three years on new hotels. Most importantly, it’s also going to launch its first own brand: Athiva Hotels & Resorts. It’s Chalet’s bet that it can run premium leisure hotels itself without paying heavy brand fees to Marriott. The first one in Khandala is already open, with five more properties to follow.

Lemon Tree Hotels

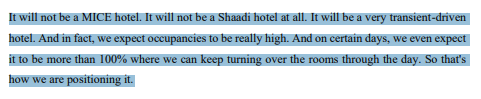

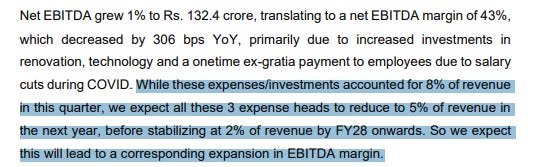

Lemon Tree had its best second quarter by revenue, which was at ₹308 crore. The RevPAR grew healthily 8% to ₹4,358, while ADR rose 6% to ₹6,247. However, EBITDA margin slipped from 46% last year to 43% now.

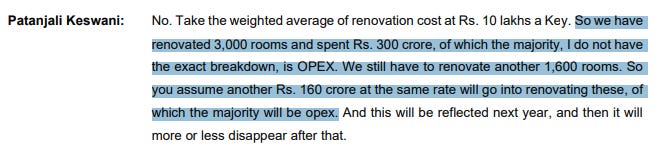

Just like IHCL, though, the margin dip is the cost of a renovation and tech overhaul that Lemon Tree is pushing through. It paused renovations during COVID, leaving a backlog of ~4,600 rooms needing heavy upgrades. They’ve now done 3,000 rooms, spending a little under ₹300 crore—most of which hit the P&L directly as operating expenses. Another 1,600 rooms remain, which will cost about ₹160 crore more. That’s somewhere around ₹10 lakhs for each room.

The renovations have already begun to pay off. Red Fox Aerocity, which was rebranded to Lemon Tree Hotel Aerocity as part of the renovation process, will now start charging a premium for its upgraded rooms. Similarly, Keys Select Pune, rebranded to Keys Prima, saw a 47% RevPAR jump post-upgrade. The management also anticipates a significant reduction in renovation and technology expenses by FY28, leading to EBITDA margin expansion.

Aurika, their premium offering, continued ramping up as well. Occupancy jumped to 75% from 50% last year. ADR is projected to significantly increase Q3 onwards, targeting ₹11,000-₹12,000 in the next winter season.

The growth ambitions are also big. The room pipeline, earlier around 20,000 rooms, is now expected to hit 35,000–40,000 rooms in the next two and a half years.

Conclusion

IHCL, Chalet and Lemon Tree each had different priorities this quarter. But the underlying principle of those priorities was largely the same — use the slow months to get work done.

IHCL shut rooms to renovate its best hotels, while also expanding for the future. Chalet is spending ₹2,500 crore on new hotels and building its own brand for the first time. Lemon Tree is halfway through renovating 4,600 rooms.

The forward view from all three is positive. IHCL expects renovated rooms to lift pricing in the December–March season. Chalet, meanwhile, expects corporate demand to stay strong as it rolls out ₹2,500 crore in new assets. Boldly, Lemon Tree targets margins to climb toward 59% by FY28.

This quarter looks less like a slowdown, and more like a sector catching its breath before the strongest months of the year.

How do companies really allocate their capital?

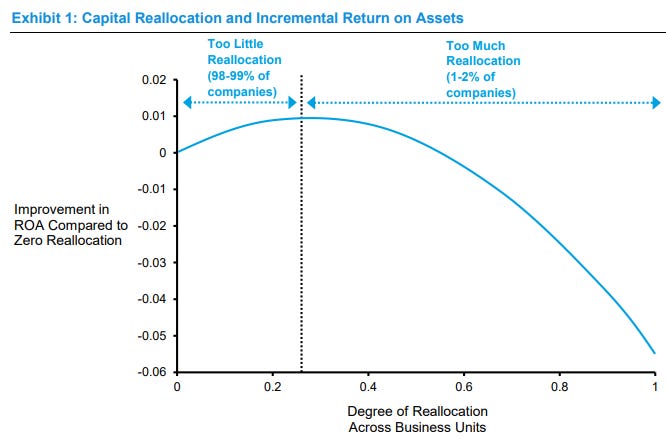

The job of every company is to decide how, where and when to allocate capital. Now, that sounds obvious and simple, but that doesn’t make it any less risky. Spending too much on factories, for instance, is just as bad as too little. Or, acquiring a company that you think will add another product to your portfolio might just end up being a huge drag rather than a value-add. Together, all of these choices eventually shape which companies grow, which stagnate, and which die.

A recent report from Morgan Stanley takes a sweeping look at how American companies have allocated capital over the past five decades. The findings are fascinating, sometimes counterintuitive, and, in some cases, even relevant for Indian markets too.

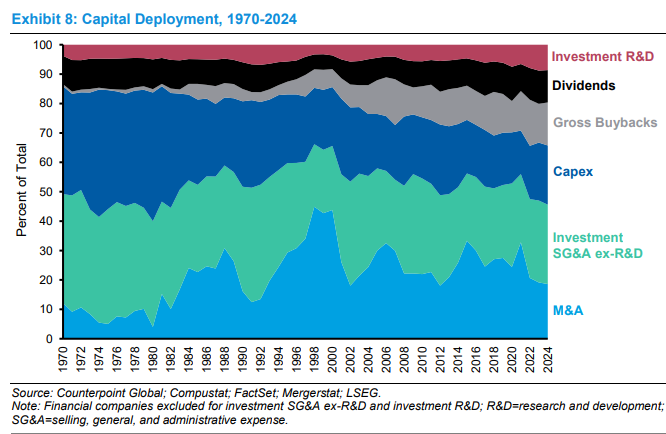

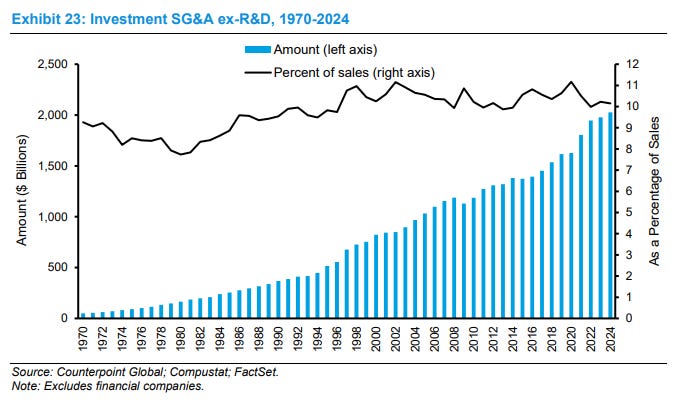

Corporate cash essentially flows into the following buckets: mergers and acquisitions (or M&A), capex, intangible investments, R&D, and shareholder returns. In fact, the share of capex has been declining in the last 50 years, while the other buckets have been broadly rising.

Each makes up a part in an interesting story about how companies choose to compete, while also giving a glimpse into how the world’s largest economic superpower works.

Let’s dive in.

M&A

M&A has become an inescapable facet of doing business in the US. In 2024, US companies spent about $1.4 trillion — or ~5.8% of total sales — on M&A. Almost 90% of publicly-traded companies engaged in at least one acquisition during the 1990s and 2000s. M&A is also a hugely cyclical business. ManieM&A activity surges when the economy is booming, while basically collapsing in recessionary situations.

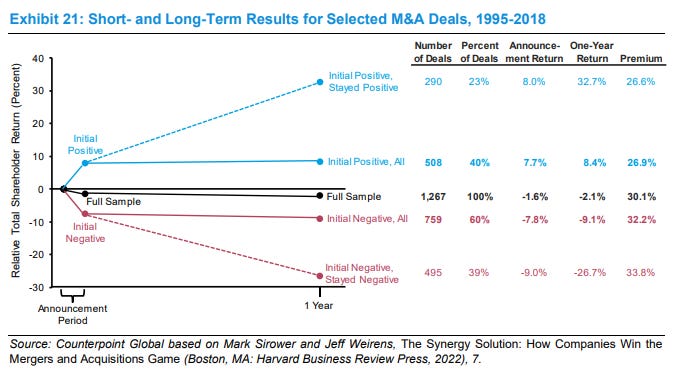

But when it comes to the question of whether M&A is really a good use of excess cash, the answer is a bit sobering. An acquisition is more likely to destroy value for the buyer than add to it, and the seller usually captures most of the value. Morgan Stanley quotes a study that found that when a deal is announced, the acquirer’s stock falls ~60% of the time, dropping 1.6% on average. The reasons boil down to the huge premium paid by buyers for the acquisition.

But there are many nuances beyond such a simple reason. Why do companies find it so hard to value the companies they’re trying to buy? Morgan Stanley’s report dives into those, too.

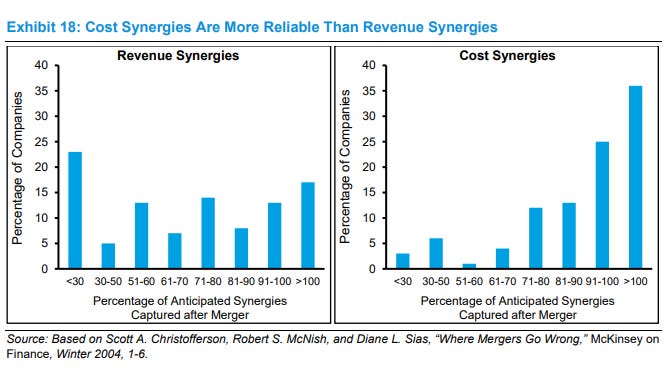

One reason is how companies evaluate synergies with their targets. Broadly, there are two types of synergies: cost synergies and revenue synergies. Post-acquisition, if the synergies match your costs should reduce significantly, while your revenues rise. However, McKinsey found that companies found it way easier to synergize on cost rather than revenue.

The reason for that is also not too difficult. Cutting duplicate operations between companies is straightforward arithmetic. But growing combined revenue requires customers to actually buy more—a much harder proposition.

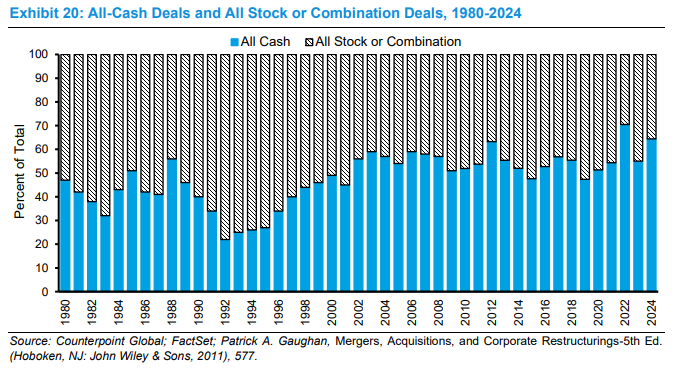

Another potential reason that determines the success or failure of a deal is how it’s paid for. Cash deals seem to outperform deals made with a mix of cash and stock. That is because stock deals are mostly used when the acquirer believes its own stock is overvalued — and as we know already, an M&A announcement likely entails a slump in the stock. Perhaps, this is why all-cash M&A deals have been rising slowly over time.

Third, deals that complement existing operations succeed more often than transformational deals that try to radically change a company’s direction. The AOL-Time Warner merger — the largest M&A deal of its time — remains a textbook example of transformation gone wrong.

What about the opposite of M&A? Divestitures — like selling divisions, spinning off subsidiaries — receive far less attention but often create more value. Research consistently shows that divesting adds value quite often — you sell off a business when it’s not doing well, or could do better independently. A division languishing under one corporate umbrella might thrive under another owner. General Electric’s recent breakup—spinning off healthcare in 2023 and energy in 2024—illustrates how a leaner scope can unlock value.

Yet, somehow, companies resist divestitures even when a division of theirs is not doing well. Why is that? That’s where the report highlights the incentives of the management. For them, selling a business means shrinking the empire, as well as admitting that they made a bad investment.

Capex and intangibles

Now, capex has been increasing in absolute numbers over time, but its share in total capital allocation has been declining. Yet, it still usually is one of the top 3 uses of capital by US companies. And usually, capex announcements are very well received by the market.

What really stood out to us was this tidbit: 60% of the capex growth in the first half of 2025 was driven by 4 of the biggest tech companies in the world — Amazon, Meta, Microsoft and Alphabet. When you think about it, though, it makes sense: Big Tech is building data centers at a rapid clip. In fact, as we covered before, data centers are the biggest driver of American economic growth this year. This capex doesn’t really represent factories as much.

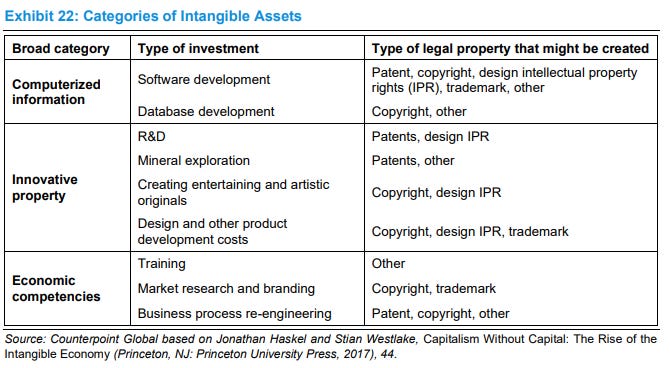

But, arguably the biggest shift in corporate investment over the past decades has been away from physical capex, to investments in intangibles: like software, brands, IPs and patents, data, customer networks, employee training.

In the 1970s, US firms spent roughly twice as much on tangible assets (plant and equipment) as on intangibles. Today, that ratio has flipped. Intangible investment now exceeds 13% of sales, while physical capex has drifted down to about 5-6%. The economy has fundamentally transformed—today’s largest companies are dominated by tech, software, and services rather than heavy manufacturing.

But there’s an interesting issue with how these intangibles are treated — even in India. When a company spends $100 million building a factory, that goes on the balance sheet as an asset. But when it spends $100 million developing software or building a brand, that’s actually treated as an expense—hitting profits directly, even if this expense generates returns for a decade like a factory investment would.

As a result, the true economic profit of intangible-heavy companies might be understated, because many “expenses” are actually investments. In fact, researchers find that capitalizing intangibles significantly improves financial statements’ ability to explain stock prices. Investors already value intangibles; accounting just doesn’t show them.

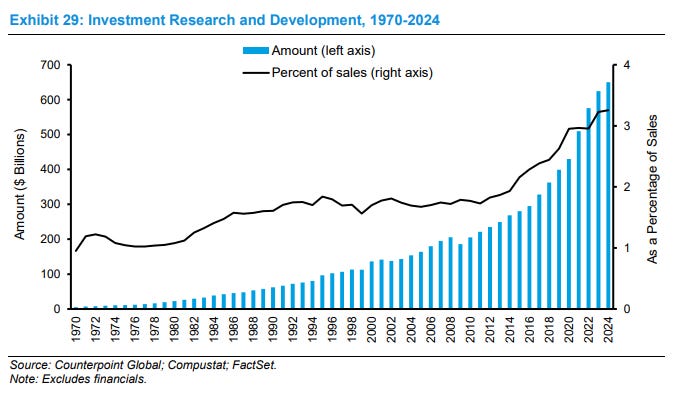

R&D

Within intangibles lies R&D, which deserves its own spotlight. After all, it’s what births new products and services. US corporate R&D spending has climbed from about 1% of sales in 1970 to 3.3% in 2024. In absolute terms, it’s at record highs. Technology and pharma are the biggest drivers of growth in R&D spend. In fact, 60% of the growth in R&D spend this year came from just 4 firms: Amazon, Meta, Alphabet and Microsoft.

But there’s a key nuance here — research and development are two separate items. Research is about exploring the unknown and generating true breakthroughs, while development means refining existing products to maintain market share. 75-80% of corporate R&D budgets go to “development“, while the rest goes to “research.”

Most R&D spend, it seems, goes not to creating new products. But that also has a simple explanation: bringing a product to market requires different skills than creating a new one. It’s why, Morgan Stanley finds, pharma firms that are better at development acquire smaller firms that are good at research,

But this connects to a deeper question: is it really effective to allocate more money to research, or even R&D as a whole? Turns out, there may be such a thing as spending too much on R&D. Morgan Stanley quotes research from Washington University that finds that many companies do overspend on R&D and get little in return. And it’s not hard to understand why: R&D is inherently risky, with more chances of failing than succeeding. It has to yield a successful product at the end of it all.

On top of this, the costs of doing R&D have actually risen over time. For instance, the cost of developing a drug and bringing it to market has skyrocketed, while approval rates have fallen. All in all, the relation between R&D and profitability is a little more complicated than just being positive.

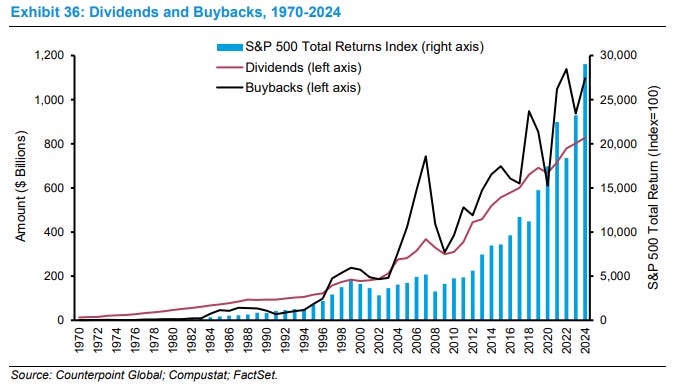

Dividends and buybacks

Lastly remain dividends and buybacks, which are ways to return excess cash to shareholders after making investment decisions. While both of them are different devices, they accomplish pretty much the same goal — giving cash back to investors.

Executives treat dividends as sacred. Once established, cutting a dividend signals trouble. In fact, the report finds that companies may even prefer to retain earnings or even borrow, rather than slash a well-established payout. Buybacks, however, are a lot more flexible. During the 2008-09 crash and even CoVID, many companies halted buybacks, while dividend payouts barely dipped.

However, even then, buybacks have gone from hardly being used 50 years ago, to being ubiquitous and even exceeding dividends in value.

And buybacks remain incredibly controversial. On one hand, critics argue companies enrich shareholders at the expense of the company’s survival itself. However, corporate finance experts disagree: if a company has more cash than it can profitably reinvest, returning it is better than wasting it on bad projects.

So, who’s right? The answer lies somewhere in the middle. There are certain times when buybacks do work: like when a stock is undervalued, or when shareholders feel that the management is spending on vanity projects rather than efficiency. To a degree, Morgan Stanley finds that companies get their buyback timing fairly right.

Conclusion

The Morgan Stanley report gives us an interesting snapshot of how American companies are deciding where to put their money. The patterns are clear: most acquisitions fail; divestitures work but companies resist them; intangibles now dwarf physical investment; R&D is essential but uncertain.

But these patterns, the report notes, also yield some simple, first principles on how to spot good capital allocators. For one, is it willing to quickly exit underperforming businesses? Or, are the incentives between management’s compensation and how well they allocate capital aligned? Or, what is the company’s attitude towards the cost of capital and access to capital? Most importantly, are they willing to overcome inertia and change strategies when needed?

To a large degree, while the report focuses on US firms, most of these principles are applicable universally. The context around each line item might change. But, just as all business works, first principles matter more than anything else when it comes to capital allocation.

Tidbits

CarTrade Tech and CarDekho parent Girnar Software have mutually shelved preliminary merger talks, with CarTrade shares closing 3.7% lower at ₹3,054.50 on the BSE.

Source: BusinesslineEmami aims to grow D2C revenue contribution to 20% within 3-4 years from current 6%, while expanding modern trade and quick-commerce channels. International business (18% of sales) expected to achieve double-digit growth amid H2 momentum.

Source: BusinesslineGPU prices for mainstream to high-end cards are finally near MSRP, while DDR4/DDR5 RAM and SSD costs have surged, with some memory kits more than tripling in price in three months.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Vignesh and Manie.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Good article on hotel industry.