India rejects $300 Billion climate deal

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Why is India unhappy with the COP29 deal?

Why is RBI letting India's forex reserve fall?

Why is India unhappy with the COP29 deal?

Every year, countries from around the world come together for a big climate summit under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). This year, the 29th Conference of Parties, or COP29, took place in Baku, Azerbaijan. These meetings aim to tackle climate change by setting goals, discussing funding, and finding ways to cut greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. But COP29 wasn’t just about ambitious goals—it quickly turned into a clash of interests, unkept promises, and growing frustration, especially for India.

Let’s break down what happened, focusing on India’s decision to reject the $300 billion climate finance deal and its strong stance on fossil fuels.

This year’s summit was hosted by Azerbaijan, a country that heavily depends on exporting fossil fuels.

This choice sparked controversy from the start, with critics accusing Azerbaijan of favoring oil and gas interests during its presidency.

The main issues at COP29 included:

Setting a new climate finance goal to replace the $100 billion annual pledge made back in 2009.

Deciding whether to phase down or completely phase out fossil fuels.

Establishing rules for carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

India found itself at the center of heated debates on both climate finance and fossil fuels. Let’s break these issues down.

So, where did this $300 billion figure come from? That’s the big question—and to answer it, we need to look back at how the climate finance conversation started.

In 2009, during COP15 in Copenhagen, developed countries promised to mobilize $100 billion every year by 2020. The idea was to help developing nations adapt to climate change and reduce their emissions.

But here’s the catch: the $100 billion wasn’t based on any detailed analysis of actual needs. Experts later criticized it as a convenient number, more about politics than addressing real problems. It was meant to satisfy developing countries without committing to something too ambitious.

The money was supposed to be split between two main goals:

Mitigation, which focuses on preventing climate change, like investing in solar and wind energy.

Adaptation, which helps countries cope with its effects, like building flood defenses or developing drought-resistant crops.

Unfortunately, most of the funding ended up going to mitigation, leaving adaptation—which poorer countries rely on—seriously underfunded.

So, how did it all play out?

The $100 billion target wasn’t met on time. According to the OECD, $83.3 billion was mobilized in 2020 and $89.6 billion in 2021. Early estimates suggest the goal was only finally reached in 2022.

But these numbers are hotly debated. Organizations like Oxfam argue that the real amount is much lower—around $24.5 billion—once you strip out loans and inflated private sector claims.

To make matters worse, the definition of climate finance is fuzzy. Many countries include spending that isn’t directly related to climate action or count guarantees that don’t translate into real funds for mitigation or adaptation projects.

At COP29, developed nations pitched a new goal: mobilizing $300 billion annually by 2035.

India’s response? Outrage. Indian officials slammed the proposal as "a joke" and accused Azerbaijan’s presidency of "stage-managing" the talks to favor developed countries. In a sharply worded statement, India said:

"This has been stage-managed, and we are extremely disappointed."

India believes this $300 billion commitment—just like the $100 billion pledge before it—isn’t a serious plan to tackle climate change. To India, it’s nothing more than a band-aid. Officials pointed out that India’s own climate goals require at least $2.5 trillion by 2030—roughly $250 billion annually.

Why does India need so much?

Energy Transition: India’s goal of 500 GW of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030 demands massive investments in solar, wind, and the infrastructure to support these systems.

Adaptation: As one of the most climate-vulnerable countries, India has to prepare for floods, droughts, and heat waves, which are expected to worsen in the future. Building resilient infrastructure comes with a hefty price tag.

Coal Dependency: Half of India’s electricity still comes from coal. Transitioning to renewable energy while ensuring a stable energy supply is a monumental challenge.

When just one country like India requires such enormous funding, the $300 billion global proposal falls drastically short for all developing nations combined. To make things worse, much of this funding would come as private financing, especially loans, which developing countries would eventually have to repay. This shifts the financial burden onto them instead of offering real support through grants.

Another major sticking point at COP29 was the debate over fossil fuels. Should the world commit to phasing them out entirely—stopping the use of coal, oil, and gas—or settle for phasing them down, simply reducing their use over time?

The controversy hit a boiling point when Saudi Arabia was accused of editing official negotiation texts. Normally, these documents are shared as non-editable PDFs to ensure transparency and fairness. However, reports surfaced that Saudi delegates had changed the wording from "phase out" fossil fuels to "phase down." This sparked outrage, with climate experts warning that such actions undermine the credibility of the negotiations and reflect a strategic effort to stall real progress.

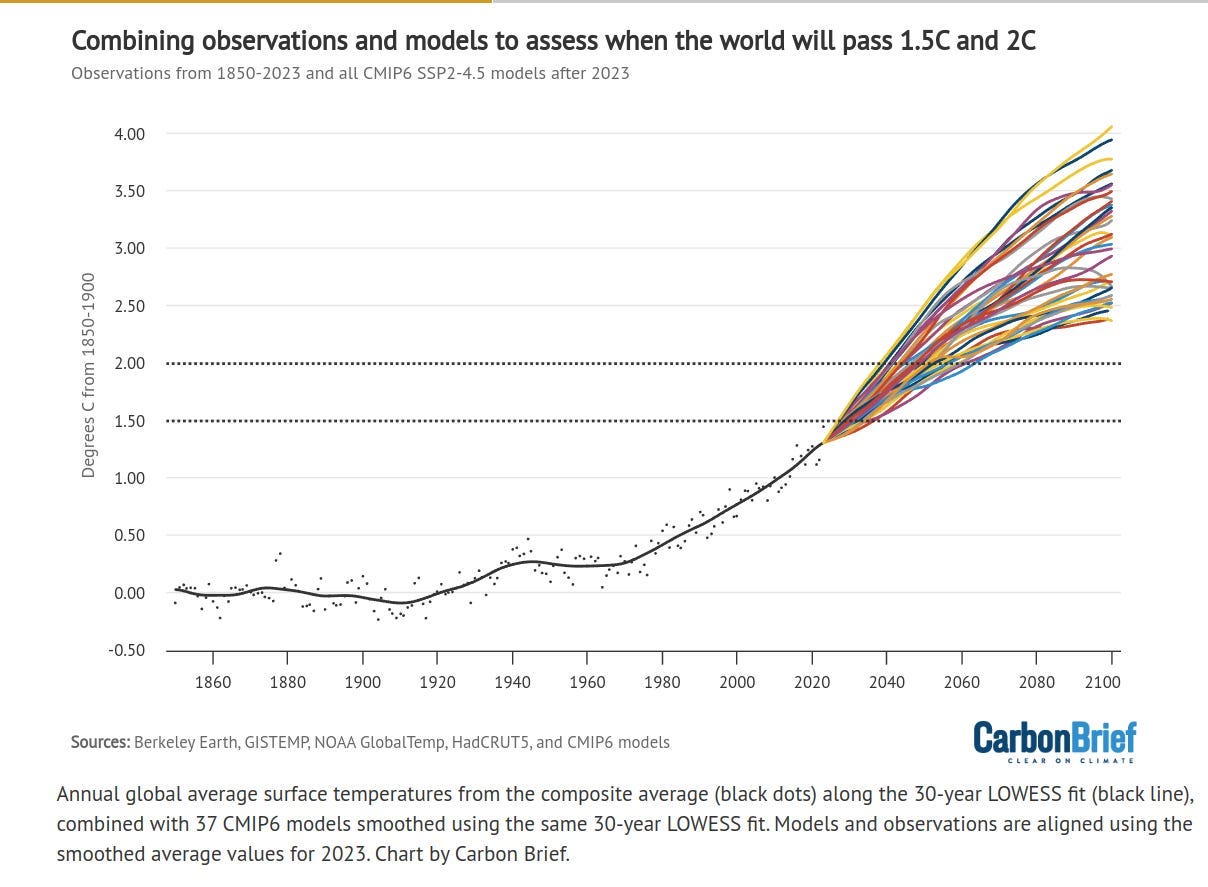

Many developed nations, led by the EU, pushed for a strong commitment to completely phase out fossil fuels. Their argument is straightforward: if the world is serious about limiting global warming to 1.5°C, we need to stop burning fossil fuels as soon as possible.

India strongly opposed a complete phase-out of fossil fuels, calling it an unfair demand for several reasons:

Historical Responsibility: Developed countries industrialized using fossil fuels for centuries, contributing the most to global greenhouse gas emissions. Now, they expect developing countries like India, which are still growing, to abandon coal and other fuels, even though they’ve benefited from them for decades.

Economic Realities: Coal still generates 50% of India’s electricity. Phasing it out too quickly would raise energy costs, hurt industries, and slow economic growth. For millions in rural areas who rely on affordable electricity, this would be devastating.

India supported a phase-down approach instead, insisting that developed nations must take the lead by transitioning first and providing financial and technological support to help others follow. However, this position was weakened by backstage negotiations.

In the end, the talks ended in a deadlock. The final agreement avoided any binding commitments on either phasing out or phasing down fossil fuels, leaving the issue unresolved. This was seen as a victory for oil-exporting countries and a setback for ambitious climate action.

India’s rejection of the $300 billion climate finance deal wasn’t just about the money—it was about fairness. At COP29, developed nations failed to offer meaningful support to developing countries, giving vague promises instead of real action. The unresolved fossil fuel debate only deepened the divide, with behind-the-scenes maneuvering further eroding trust.

As we look ahead to COP30 in Brazil, one big question looms: can global climate action ever truly be fair, or will the gap between the Global North and Global South keep growing?

Why is RBI letting India's forex reserve fall?

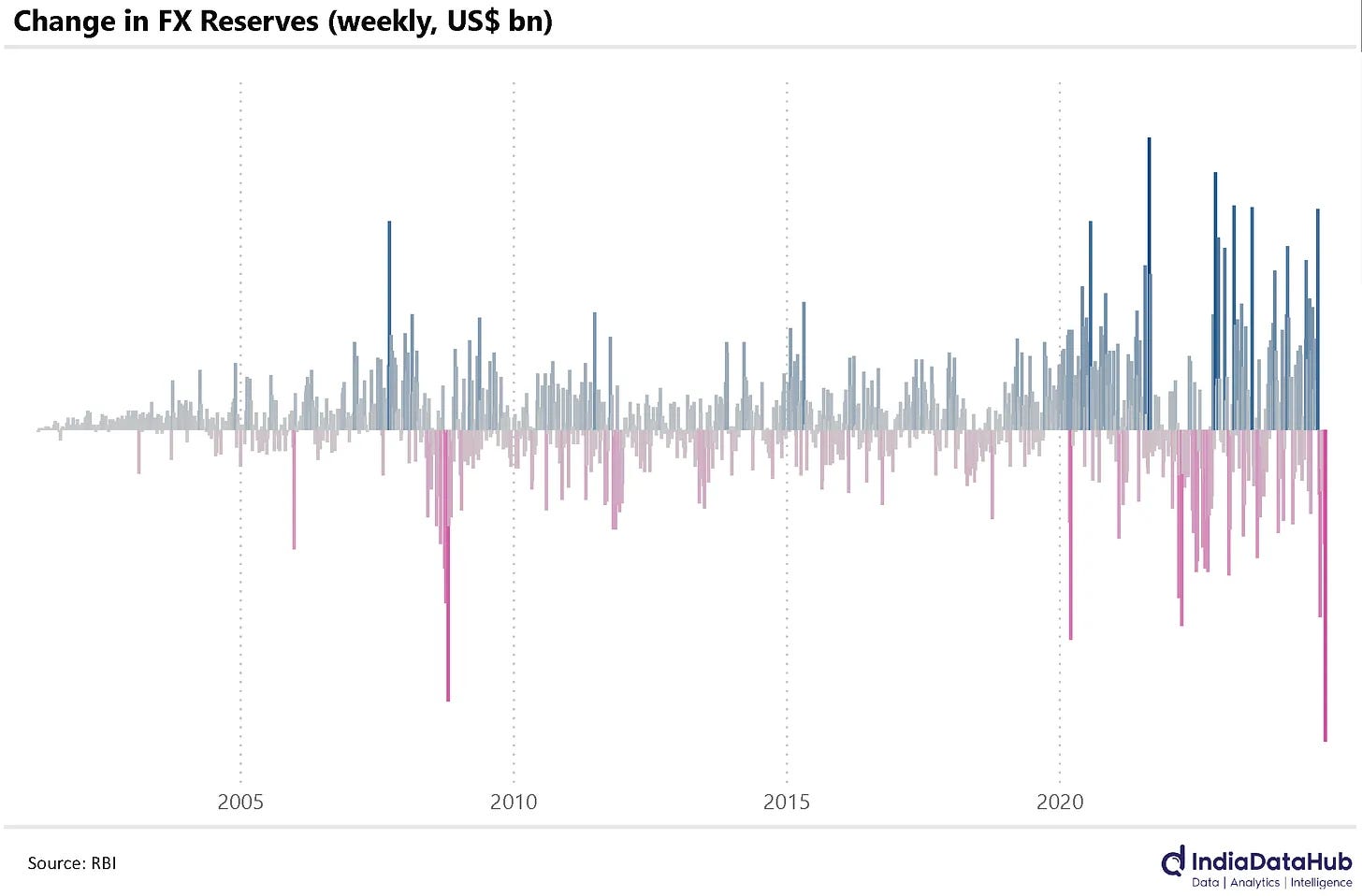

India’s forex reserves just took their sharpest weekly hit ever, dropping by $17.8 billion in just one week. That’s like smashing a piggy bank with a wrecking ball. Over the past seven weeks, the reserves have fallen by nearly $50 billion—a decline of almost 7%.

To put this in perspective, the last time we saw a drop of this size was in late 2008, during the global financial meltdown. Even during the taper tantrum in 2013, the reserves didn’t shrink this dramatically.

So, what’s behind this steep decline? A big part of the story is how the RBI is managing the rupee’s value—and why it’s not letting the currency float freely, like a boat in open waters. Let’s break it down.

Why Are Forex Reserves Falling?

The main reason is foreign portfolio investors (FPIs). These investors, always on the hunt for the best returns, tend to shift their money based on global and local market conditions. Lately, India hasn’t been their top pick.

In November, FPIs sold over $4 billion worth of Indian stocks and bonds. Why? The reasons can change quickly. One day, China’s new economic support measures might make it more attractive. Another day, a stronger U.S. dollar after elections pulls money toward the U.S. Or it could be concerns about India’s domestic growth, weak corporate earnings, or high stock valuations.

The key takeaway? FPIs are driven by returns, constantly reallocating to where they see the best opportunities. Their actions often reflect global trends rather than any specific judgment on India’s markets.

But there’s more to this story. The drop in forex reserves isn’t just about FPIs pulling out. The other big player here is the RBI.

How the RBI Manages the Rupee

When foreign money flows in or out, it changes the demand and supply for the rupee against the dollar. In a floating exchange rate system, this would cause the exchange rate to swing widely. But the RBI steps in to prevent that.

Why? A volatile exchange rate creates uncertainty for businesses, investors, and ultimately for all of us. A stable rupee helps keep the economy predictable.

Here’s how the RBI does it:

Earlier this year, when dollars were pouring into India, the rupee should have strengthened. But the RBI bought up those dollars and added them to forex reserves, preventing the rupee from appreciating too much.

Now, as foreign investors are pulling out, the rupee should be dropping sharply. But the RBI is selling dollars from the reserves to keep the rupee steady.

Why This Matters

Even with the recent jump above 84, the rupee has depreciated by less than 1% over the past year. Over two years, the depreciation is under 2%. That’s a big deal because, over the past two decades, the average two-year depreciation of the rupee has been around 7%.

The RBI’s efforts to stabilize the rupee have helped shield the economy from the worst impacts of volatile foreign exchange markets. However, these interventions come at a cost—our forex reserves. And as we’ve seen, they’re shrinking fast.

The rupee has been one of the most stable currencies among emerging markets. Over the past three months, it has moved just 0.6% against the USD. In comparison, Russia’s ruble dropped by a steep 12.4%, and even the Singapore dollar weakened by 3%.

While global currencies have been swinging wildly, the rupee has held its ground. This stability is thanks to the RBI’s active intervention, using its forex reserves to keep the rupee steady.

How Does This Impact You?

In the short term, this stability is a good thing. By stepping in to control the exchange rate, the RBI is preventing a domino effect of problems.

Think about it—if the rupee were to drop sharply, everything we import, like oil, electronics, and food, would become much more expensive. That would drive up inflation, and we’d all feel it directly in our day-to-day expenses.

By using its forex reserves to stabilize the rupee, the RBI is acting as a buffer, shielding the economy—and all of us—from these bigger shocks. It’s a tough job, but for now, it seems like the right move to keep things steady and avoid unnecessary hits to our wallets.

The Long-Term Trade-Offs

In the longer run, the RBI’s focus on stabilizing the rupee has its own challenges. This approach is a policy choice, and like any choice, it comes with trade-offs.

When the RBI buys or sells dollars to manage the rupee, it’s working to keep the exchange rate stable. But this can come at a cost:

It may limit the RBI’s ability to carry out other important tasks, like setting interest rates or managing inflation effectively.

Over time, this could hurt the broader economy if monetary policy becomes less flexible because of the focus on exchange rates.

There’s also the issue of disrupting capital flows. Every time the RBI steps in to influence the rupee, it affects how money moves in and out of the country. For example, when imports become cheaper, exports often get more expensive. While that might sound good for consumers in the short term, it can hurt our ability to earn as a country by making it harder for businesses to sell goods overseas.

Then there’s the ripple effect on liquidity. When the RBI buys dollars, it gets them from Indian banks and pays in rupees. This increases the amount of rupees in the financial system. If there’s too much liquidity, it can lead to inflation. On the other hand, when the RBI sells dollars, it takes rupees out of circulation. This can tighten liquidity, making it harder for businesses to borrow and potentially slowing down economic growth.

So, while stabilizing the rupee helps in the short term by controlling inflation and keeping borrowing costs steady, it can cause other problems over time. It can distort markets, reduce flexibility in policymaking, and create unintended consequences for the economy.

At the end of the day, it’s all about trade-offs—difficult, complex decisions where every action triggers a chain of effects. The RBI’s job is anything but simple, and every move it makes is just one piece of a much bigger and more intricate puzzle.

Tidbits

Bangladesh’s interim government is reviewing major power deals, including Adani’s 1,234.4 MW Godda plant, following allegations of overpricing and unpaid bills. This investigation could lead to renegotiations, financial setbacks for Adani, and strain energy ties between India and Bangladesh.

Mercedes-Benz and BMW India are set to raise prices by up to 3% starting January 2025, citing higher input costs. Customers can secure current prices by booking before January or opting for flexible financing options.

Government-owned ports saw a 3.2% drop in cargo volumes in October 2024, mainly due to lower shipments of crude oil and coal. In contrast, private ports, led by Adani Ports, reported a 5.7% growth, showcasing their competitive advantage.

The ₹1.97 trillion PLI scheme has driven ₹13 trillion in production but is facing challenges in sectors like textiles and AC components. The government is pausing further expansions to address these issues and stabilize struggling industries.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

To the point, the daily brief is a goldmine.

Insightful, concise and impactful

irrespective of RBI intervention, wouldn't FII investment lead to more liquidity in Indian markets, and FII withdrawal lead to less liquidity, could you pls clarify this :)