India makes its first moves in the global chip market

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Unravelling India’s chip play

When central banks try to revive a dead economy

Unravelling India’s chip play

Yesterday, we traced the raging global war over the future of semiconductors. India, in comparison, is a relative backwater. While the world is locked in intense competition at the very edge of what is possible, we’re still learning how to start our chip journey.

The fact that India’s chip industry is primitive, though, doesn’t mean it is unexciting.

Late in 2021, India began an ambitious program to create a domestic chip ecosystem. This wasn’t the first time we had embarked on such a project — India’s first semiconductor foundry was set up way back in the 1980s. But while that project ran on the back of a PSU, and hoped to replace our reliance on global supply chains, this latest push has been something different. We’re trying to enmesh ourselves in a pre-existing chip ecosystem — positioning ourselves as a secure, reliable, and collaborative partner to global firms.

This time around, there are reasons for hope. The program has seen some genuine successes, with leading firms across the world showing interest in India. This isn’t a guarantee of success, of course. There’s a long way to go before we have anything resembling a mature chip ecosystem. But this is an interesting beginning.

India’s strategy

Chips are some of the most complex pieces of technology we’ve ever put together. Doing so requires one to work with a range of components produced across the world, sourced from some of the most complex supply chains ever put together. It’s practically impossible for India to enter this industry from scratch. And so, India is trying to attract established leaders from countries like the United States, Taiwan, and Japan.

Global partners bring a range of advantages with them. Most crucially, they bring the benefit of know-how that they’ve developed over decades. They’re also the only ones with enough capital to create a new industry from scratch. Moreover, they also bring massive business networks with them. Consider the entry of Micron: when it entered India, an entire ecosystem of suppliers — sellers of raw materials, utilities providers, service providers and more — co-located with the company, setting up their own investments around Micron’s factory.

But why would a leading chip company come to India? Well, because India is throwing in a lot to sweeten the deal. The central government has announced generous incentives to pull foreign players in, complemented by programs that individual states have rolled out.

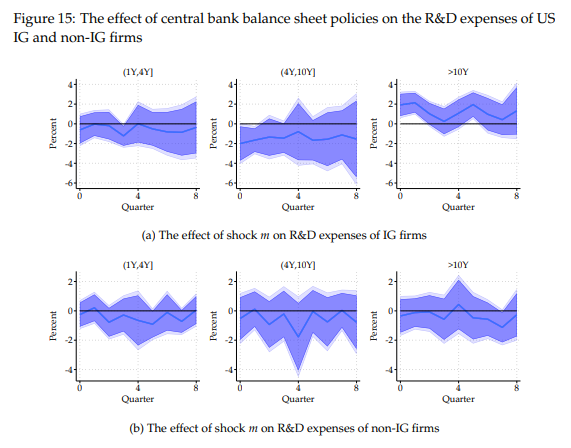

The central pillar

At the heart of India’s efforts is its massive ‘Semicon India’ program: which was given $10 billion to spend on attracting global giants. Its promise is simple: if anyone set up a chip factory in India, we would pay for half the capital costs the project would take, on an equal footing. This held true regardless of what part of the value chain you were in — chip fabrication, displays, assembly, testing, and more. Whenever a private company put in its own investment, the government would match that amount.

To execute this ambitious program, the government set up an independent business division — the ‘India Semiconductor Mission’.

Although this scheme has brought in a lot of projects, it has seen serious execution challenges. It tried pulling in complex, best-in-class projects — which required heavy funding, and complex technological tie-ups. While it generated a lot of interest, many projects fell through.

Recently, however, the government has floated proposals for a second version of the program. This time around, reportedly, the program will be funded with $20 billion. But more importantly, it promises to broaden the scope of the projects it shall pursue. While details of the program aren’t out yet, it shall reportedly approach smaller, more specialised projects — compound semiconductors, assembly units and the like — which could eventually stitch themselves into an entire ecosystem.

The state contest

Beyond the central incentives, there’s an active competition between various states to draw semiconductor projects to their own borders.

It began with Gujarat, which came out with a semiconductor policy back in 2022 — setting up massive plug-and-play industrial zones that chip-makers could link into — such as the Dholera special investment region. It also offered an extra 40% capital assistance over-and-above what the central government’s would give, essentially promising that if you set up a unit in Gujarat, 70% of your capital expenses would be covered.

Since then, a variety of other states have thrown their own hats into the ring.

Karnataka, for instance, recently announced a semiconductor policy for the years 2025-30 — promising capital subsidies, cheap power, and a range of other sops. Tamil Nadu, too, has come out with a semiconductor policy, with subsidies more closely linked to job creation — covering half the basic pay of all employees at a chip factory for three years.

While these already have extensive engineering and technology, a range of other states are also making a play to draw more companies in — from coastal states like Andhra Pradesh and Odisha, to even those far inland, like Uttar Pradesh and Assam.

While many of these might not bring the results they’re looking for, to potential investors, India currently offers an exceedingly generous set of options to choose from.

The journey so far

All these schemes, combined with relentless effort towards building more business opportunities, have shown real progress over the years. They have come through step-by-step, with many false starts and heartbreaks along the way. They’re best understood by looking at every step along the chip supply chain.

Chip design

Designing a chip is a matter of exceptional precision — with billions of transistors that need to be placed just right, where the slightest design flaw can mean millions of wasted dollars or months of delay. Most of the intellectual value that goes behind a chip — which translates into the fat margins that companies like Nvidia or AMD earn — comes from this stage.

With its large pool of engineering talent, Indian entered the chip design space a long time ago. And this is where it has its biggest advantage. Roughly one in every five of the world’s semiconductor design engineers — over 50,000 of them — are in India. We host R&D centers for nearly every major chip firm – including Intel, AMD, NVIDIA, Qualcomm, Texas Instruments, and MediaTek, among others.

To bolster this ecosystem, the government came out with a “designed-linked incentive scheme”, earmarking ₹1,000 crore to support startups and companies in chip design. So far, the government has backed 23 start-ups under this scheme. These startups are working on a range of products – from IoT chipsets and sensors to 5G radio chips – and the scheme provides grants and mentorship to help them succeed.

We’re also drawing in major investments from global design majors. In 2023, for instance, U.S. chipmaker AMD announced a major $400 million investment to expand its R&D presence, opening its largest design center in the world in Bengaluru.

Some Indian conglomerates have jumped into the fray as well. For instance, engineering giant Larsen & Toubro (L&T) announced, in late 2023, that it will invest over $300 million to create a fabless semiconductor company in India.

Fabrication

In the grand scheme of things, though, a chip fabrication plant is the holy grail for our semiconductor mission. This is where chips are actually created, and their requirements border on science fiction. They’re arguably the most sophisticated factories ever built; costing upwards of $10–20 billion, and taking years to come online. Such a project also marks a major economic challenge — they’re only viable if it operates at massive scale, churning out millions of chips to justify the investment.

If we’re actually seeking technological sovereignty, the ability to fabricate chips is perhaps the most crucial piece of the puzzle. But setting one up is also the hardest challenge we face. And our attempts at doing so have been littered with disappointment.

One of the most high profile projects in the works, for instance, was a partnership between Vedanta and Taiwan’s Foxconn to set up a fabrication unit in Gujarat — envisioned as a $19.5 billion joint venture. The government, however, held back on approving the project and disbursing money, questioning the costs the partnership had cited. After a year of trying to make things work, Foxconn pulled out, effectively killing the deal.

Similarly, Israel’s Tower Semiconductor and the Adani Group had announced a much-touted partnership for a $10 billion fabrication project. Last year, however, well into the project — after the Maharashtra government had announced approval for the project — talks broke down, supposedly because there simply wasn’t enough demand to justify such an investment.

But there is one big success we’ve reached in this department — Tata Electronics has partnered with Taiwan’s PowerChip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (PSMC) to build India’s first new wafer fab in Dholera, Gujarat. This is a $10 billion project, which, once successful, will churn out 50,000 wafers per month. Construction has already started, and Tata has sent hundreds of engineers to Taiwan for training.

Now, this facility is nowhere close to the cutting edge. While the global frontier in chips has touched 2 nm — barely 10 silicon atoms end-to-end — the Tata-PSMC project is for more “mature” chips. The partnership will start with 28 nm chips. That isn’t nearly good enough for cutting edge AI applications. They can, however, be handy for less sophisticated technology, like the chips used in industrial machines, or receivers in phones.

It is still, however, the crowning achievement of our semiconductor program so far.

Assembly, testing, marking, packaging

Once a wafer is fabricated, it goes through a lengthy process before it can actually be used in a computer. That’s where ATMP — assembly, testing, marking, and packaging — comes in. This is often dismissed as the “back-end” of chipmaking, but when it comes to chip-making, nothing is simple. ATMP is a high-tech challenge in itself, requiring precision at microscopic scales.

This is where India’s semiconductor program has found the most success in drawing foreign firms.

The marquee investment came from U.S. memory maker Micron Technology, which in mid-2023 announced a $2.75 billion project to build an advanced semiconductor assembly and test plant in Sanand, Gujarat. This was, at the time, a game-changer for India’s chip ambitions. It validated India as a destination for top-tier semicon firms, arguably pulling in many of the investments that followed.

Another major assembly unit has come in courtesy Tata, complementing its fab. The company is investing ₹27,000 crore in an OSAT (Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test) plant in Assam. Meanwhile, Foxconn, after the failure of its fabrication plans with Vedanta, pivoted to assembly. Partnering with HCL, it is investing another $430 million for an OSAT plant in Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh.

These are just some of the ATMP projects that India has green-lit. There are multiple such facilities under construction all over India. This is transformative. Until now, India had almost no high-volume chip packaging capacity. These units, once fully operational, will process 70 million chips per day. It may well be the stepping stone we need to more complex chip manufacturing.

Making sense of where we are

India’s semiconductor program has only been around for four short years. Despites its many fits-and-starts, the program has managed to catalyse an exceptional degree of investment, delivering tangible progress. India has already approved 10 major projects, with a total committed investment of around $18+ billion across 6 states.

It’s worth remembering how precarious things still are. For now, much of India’s semiconductor program still lives on construction sites and in signed MoUs. The real test will come when all the plants under construction actually start production. Only then will we know if the economics adds up, and if there’s a real market for “Made in India” chips.

A truly independent, indigenous industry is further away still. Right now, we have a program that depends on foreign anchors: like PSMC, or Micron. Without them, the scaffolding collapses. We still don’t have a deep well of knowledge and experience built here, in India. That’s why, even with billions already committed, the industry remains precarious, dependent, and unproven.

And ultimately, from where we stand, the cutting edge is a distant dream — perhaps a generation away.

But for all this, we have a genuine foothold in one of the most complex industries in the world, and that alone is worth celebrating.

When central banks try to revive a dead economy

In an ideal world, when an economy slows down, the central bank rides to the rescue. It announces rate cuts, businesses get cheaper loans, investment picks up, and growth returns. The standard playbook is enough to get the job done.

But, there have been a few extraordinary times in major economies when things didn’t go to this plan. You could cut rates all the way to zero, but the economy still won’t budge. There’s still one trick up a central bank’s sleeve, though one it must use sparingly: quantitative easing (QE). This is when a central bank sidesteps traditional rate cuts, and starts buying government bonds, directly flooding the economy with money.

QE was once a rarity. It was the “nuclear red button” option, to be avoided unless things got really bad. But since Japan first tried it in the 2000s, QE has become surprisingly commonplace. Central banks across the world have collectively pumped trillions of dollars into financial markets using QE.

But here’s the literal trillion-dollar question: does QE actually boost real economic activity? What’s the real impact of QE on how we do business? A fascinating new paper from the Bank for International Settlements goes into how QE affects how companies operate.

Let’s dive in.

When normal doesn’t work anymore

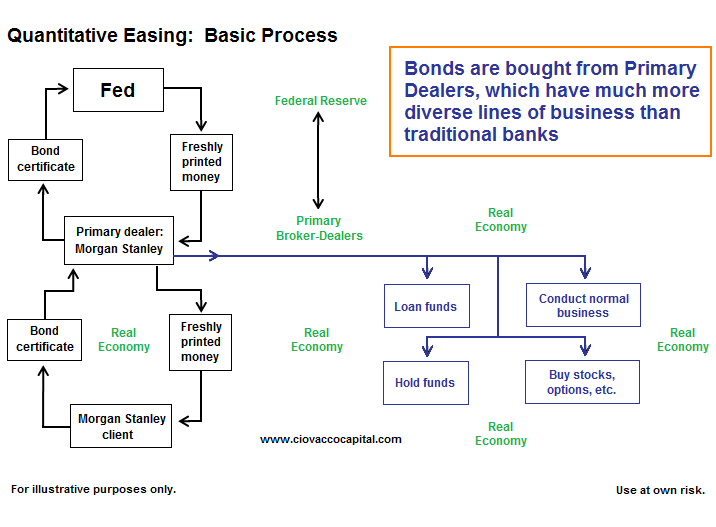

First, let’s see how QE works.

For that, we must first understand normal monetary policy. We’ve covered this before, but here’s a quick summary. In normal times, the central bank cuts the repo rate — the rate at which the central bank lends overnight to commercial banks. This cut is “transmitted,” starting from there, to the rest of the economy. Once the central bank makes money more easily available, banks lower short-term interest rates. This means cheaper loans, encouraging businesses to invest, and regular consumers to make big purchases.

But there’s a clear baseline to this. Once rates have gone to zero, the central bank is out of space to maneuver. What if the economy is still slowing down? What if commercial banks still find little incentive to issue more loans? Lowering rates further, at this point, makes little sense. The strategy has effectively broken down.

That’s where QE comes in. It changes the transmission channel through which rates are lowered, in two ways. One, it bypasses banks. Two, it affects long-term interest rates instead of short-term rates.

Here’s how it works. Using money created digitally, the central bank directly buys safe assets like long-term government (or corporate) bonds from investors or bond dealers. This pushes up the prices of those bonds, while lowering their yields. It puts money in the hands of investors, while making the economy’s safest investments less attractive by pulling down the returns. Those investors might now make bigger, riskier investments.

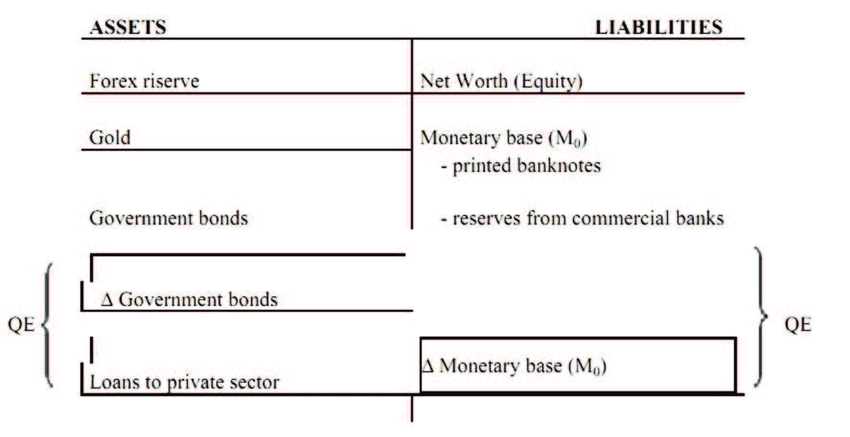

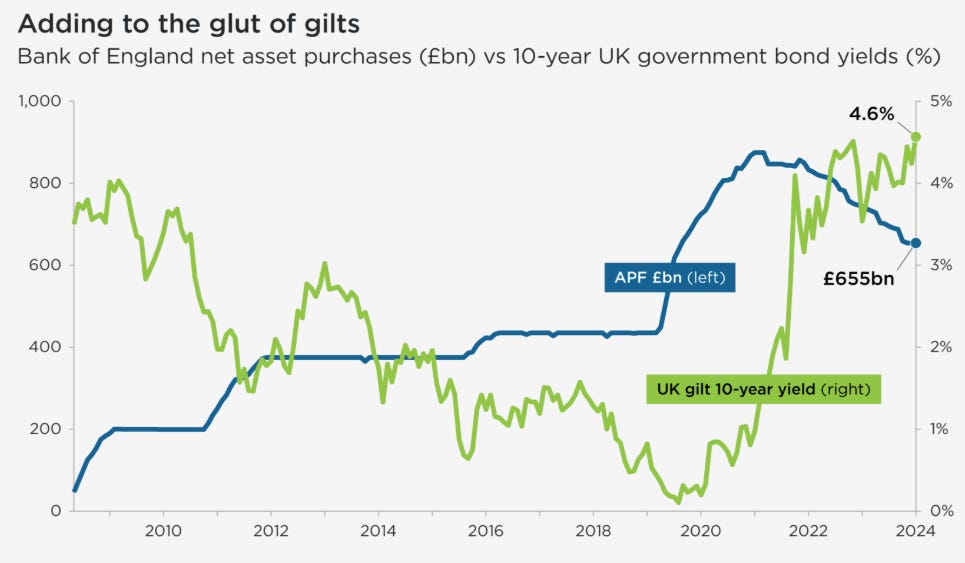

At the same time, this expands the size of a central bank’s balance sheet. It acquires more bonds that become assets, while the money it creates becomes a liability.

Functionally, through QE, the central bank tries to expand and alter the structure of the balance sheets of investors by expanding its own. At the end of it, ideally, investors’ balance sheets would contain more risky loans, less safe assets, and more cash.

QE comes with trade-offs, though. It essentially pumps new money into an economy, while enabling a massive expansion of government spending. It might be able to prevent economic collapse in a crisis, but all that money has to go somewhere. Usually, it ends up in asset markets of all sorts, inflating prices and worsening inequality. At the extreme end, it can increase inflation significantly. — This is why they’re usually a last resort.

Quantitative tightening (QT), meanwhile, is the reverse. Central banks sell bonds, drain cash from the system, and tighten financial conditions. But as we’ll see soon, while it sounds like the mirror image of QE, it might not be in effect.

Intended policies, unintended (non)effects

With that out of the way, let’s see what the BIS paper finds.

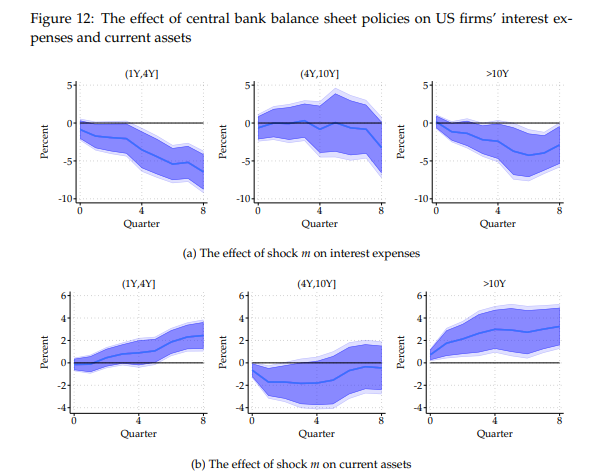

The BIS researchers discovered something interesting — and concerning — about how firms react to QE across countries. When a bank performs QE, firms change how they borrow. But, importantly, they don’t necessarily borrow more, overall.

The first part makes logical sense. When a central bank is buying long-term bonds, it gives companies an opening to swap out their own short-term bank loans with long-term bonds. This helps them delay interest payments that otherwise, they would have to make early. In simpler terms, they get to restructure their existing debt. This, in turn, boosts their cash holdings — and their financial health.

But that’s where things break down.

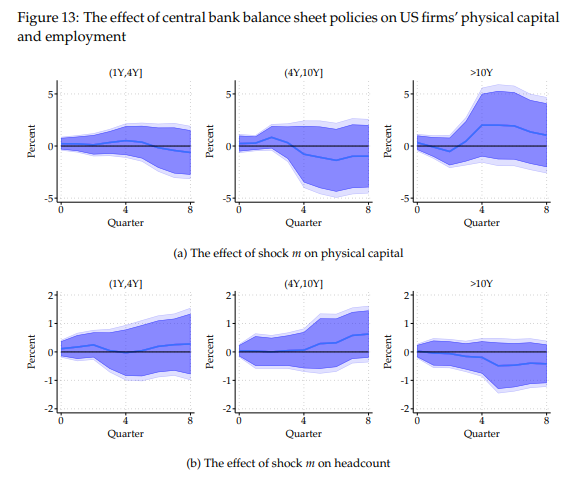

The point of this exercise, in theory, is to let businesses borrow more, so that they can make investments that truly matter to the economy. On that front, it turns out, QE has generally remained disappointing. It leads to negligible expansion in capital expenditure or even employment.

Just because companies have more money doesn’t always mean they’ll invest it.

In fact, there is evidence from Viral Acharya — the ex-Deputy Governor of RBI — that QE pushes companies to do more financial engineering than real investments. When QE adds money to the economy, M&A activity explodes and share buybacks multiply. Companies, it seems, are more likely to reward shareholders rather than build new factories.

The BIS doesn’t completely agree with him. Their data finds mixed evidence.

But even so, let’s think for a minute about the implications of all this. To the BIS, QE doesn’t really succeed at what it sets out to do. When an economy is down, that extra money does little to push it up. It doesn’t introduce more confidence in the economy that things will improve.

Ultimately, to invest, a company needs to believe it could prosper if it invested in growing its business. And QE is incapable of doing that. While QE changes the numbers, it doesn’t actually change the attitudes of companies over long time horizons. Instead, when QE brings in more cash, companies use it to make themselves more cash-rich.

Not all firms are created equally

There’s nuance to these findings, though.

The effects of QE vary dramatically depending on two things: what kind of company you are, and the maturity period of your bond.

Creditworthy firms — which are usually also huge — always hit the jackpot during QE periods. Their bonds are popular, and when interest rates on government bonds shrink, they see a surge in demand. But from there, things can get weird. When the Fed bought 10-year Treasury bonds, for instance, large firms increased their R&D spend by ~2%. Perhaps, QE does create some productive investment after all, just not by promoting more borrowing.

On the other hand, though, QE’s impact on non-creditworthy, smaller firms is muted. Small firms are far more strapped for resources than their larger peers, and find it hard to raise bank loans, or borrow money from the bond markets. QE does not make things easier for them. Their long-term bonds don’t get more popular, regardless of how well government bonds are doing.

QE also doesn’t make them invest more in R&D.

In effect, this increases inequality between firms in the economy. Large firms find it far, far easier to borrow money in periods of QE, even more so than normal market conditions. Small firms with credit crunches, however, don’t have their life made any easier by QE.

Two more findings

Two other findings from the BIS study reveal the complex psychology of monetary policy.

Firstly, in the medium-term, the expectation that a bank shall announce QE matters almost as much as the actual QE. That is, firms don’t wait for the central bank to do anything. The mere promise of support changes how they think. They start adjusting their behavior as soon as QE is announced.

This explains why QE announcements often have immediate market impacts, even though the actual asset purchases are spread over months or years. The market prices in the policy support instantly, financing costs change, and with it, investment calculations flip across the economy.

Secondly, the BIS finds that firms respond much more dramatically to QE than to QT. When central banks start buying bonds, companies rush to issue bonds and reshape their financing. But the opposite doesn’t happen! When central banks reverse course and start selling bonds (QT), the response is far more muted. That said, that there have been far fewer instances of QT in history than QE, so the sample size of this finding is low.

What does this mean? Once you commit to QE, you can’t roll back the effects. QT cannot simply undo the effects of QE — the policies are not really mirror images of each other. If companies have locked in cheap long-term financing and built up cash reserves, they don’t reverse these decisions when central banks tighten policy.

In fact, not long ago, the Bank of England struggled with this. It tried to combat the inflation caused by QE, but QT refused to do much.

The money shuffle continues

In all, both QE and QT seem to be quite ineffective in what they set out to achieve.

There’s a clear benefit to QE: it’s solid at preventing financial collapse and facilitating balance sheet engineering. But while it avoids collapse, it can’t create growth. It’s mediocre at driving the productive investment and job creation that is the very basis of economic growth.

QE isn’t worthless. Preventing economic meltdown itself has enormous value. But it does suggest that central bankers have been overly optimistic about its promises to revive entire economies. Shuffling financial claims, however expertly done, is hardly a substitute for creating real economic value.

Tidbits

Swiggy is going to offload its entire 12% stake (worth $270 million) in Rapido. The reason they’ve given is Rapido’s entry into food delivery has created a conflict of interest with Swiggy. This sale values Rapido at $2.3 billion while giving Swiggy a solid return on its investment. At the same time, Rapido wants to raise an additional $500 million.

(Source: TOI)The US isn’t stopping at just stricter H-1B rules to crack down on immigration. Senator Jim Banks introduced the “American Tech Workforce Act”, which would raise the H-1B wage floor from $60,000 to $150,000, making Indian workers far more uncompetitive. This is particularly aimed at Big Tech companies, who were accused by Banks of putting the interest of Americans last by outsourcing jobs out of the country.

(Source: Business Standard)The world’s cocoa crunch — which we covered some time ago — is finally showing some signs of relief. Cocoa production is forecast to outpace consumption in the new season starting next month. Good harvests from South America and waning demand have helped stabilize cocoa prices.

(Source: Bloomberg)

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Manie

So, we’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

📚Join our book club

We’ve started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we’d love to have you along! Join in here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

The current approach to nurturing a domestic tech ecosystem, characterized by typical GOI quasi operational involvement and a non-strategic scattershot of incentives and subsidies; is fundamentally flawed. It's a low-yield strategy rooted in outdated industrial policy.

India's best bet isn't to be a competitor; it's to be the gatekeeper to a billion-plus consumer market. The immediate, high-ROI move is to shift the GOI's function from that of a hands-on operator to a strategic and ruthless policy architect.

My proposal? Pivot from carrots to tollgates.

Discard incentives (carrots) for mandatory requirements (tollgates).

Like China, use the 1.3 billion-person market as leverage:

• Want to sell iPhones or Pixels? Build it here.

• Want to sell Search or Social? Keep the data here. Leverage Sovereign Data.

This market-access mandate solves the tech lag far better than bureaucrats designing "Make in India" programs. Compel, don't subsidize.

SPEL is been there for many decades but we in India lack Vision. That's why all this atmanirbhar etc.. seem rhetoric and fizzles off after few months. We never follow things up. I don't want to be sarcastic but couldn't help. Sorry