India bets on interest rate derivatives

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India bets on interest rate derivatives

A primer on the auto ancillary business

India bets on interest rate derivatives

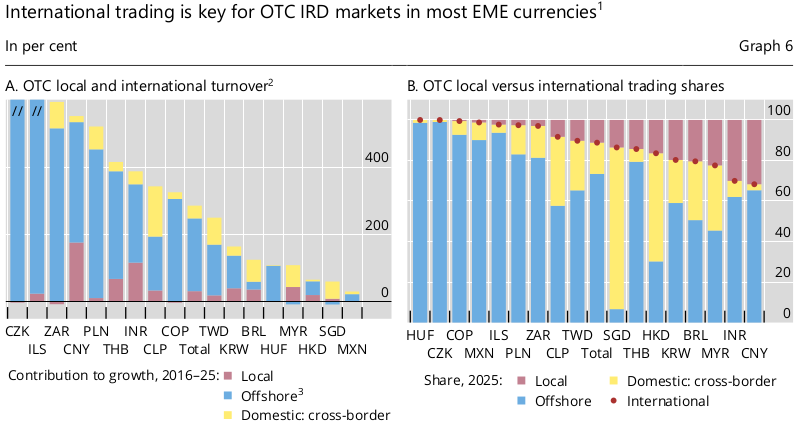

Recently, two developments caught our attention. The first was a new set of Master Directions from the RBI, which could deepen India’s market for interest rate derivatives. The second was a paper published by the Bank of International Settlements, which thinks that the world’s booming interest rate derivatives market could create severe stress across its financial system.

Naturally, we were curious.

We aren’t suggesting, for a moment, that RBI is inviting financial collapse. Far from it — this market is big, across the world, because it is useful.

But this is a big change. So far, the RBI saw India’s interest rate derivatives market as having a limited purpose — letting large financial entities hedge some bets. And yet, lakhs of crores would be traded on it every month. With its new changes, the RBI is signalling that this is an important financial market in its own right. It is, in effect, unshackling a giant.

This is a market that’s usually obscured from laypeople. It’s meant for sophisticated entities — banks, governments, pension funds, and others — to balance their enormous flows of money. But we wanted to understand exactly what it entails; how these markets work, who they serve, and where a failure could come from.

Let’s jump in.

What in the world is an interest rate derivative?

You probably know that there’s an economy-wide cost of borrowing money, which is what the RBI tries to control through its repo rate. If you’re someone that deals with brain-curdling amounts of money — like a bank or a pension fund — the fate of your business can depend on what this rate is.

Put yourself in the shoes of a bank. Your business model is to borrow money from people at one rate, lend it at another, and pocket the difference. Now, imagine: while borrowing, you promise to pay interest at a rate that “floats” with the economy-wide rate — which is currently, say, 5%. On the other end, you might give out fixed-rate home loans, say at 8%. If everything stays the same, you pocket a neat 3% margin. But if interest rates climb, suddenly, those profits start to disappear.

Similarly, imagine you run a pension fund. You have a rough idea of what you might have to pay ten years from now, to everyone who retires then. So, you invest in bonds, calculating that the interest you earn will cover those payments. But suddenly, interest rates fall, and that yield disappears. Your calculations are wrecked.

A change in interest rates, essentially, is a source of risk for many businesses. But you can plan around these problems — by taking side-bets.

Imagine, for instance, that the bank and the pension fund meet. The bank is terrified that interest rates will go up. The pension fund is afraid that they might go down. The two can strike a deal: if interest rates fall, the bank pays the pension fund, and if they go up, the pension fund pays the bank. Between them, they remove the uncertainty of moving rates.

These side-bets are “derivatives”. They don’t change the main business of either entity, and they don’t affect the interest rate. They’re simply arrangements that derive their result from how interest rates might move.

There’s a massive market for these side-bets. Institutions come here with their unique fears, shaped by how they’ve lent or borrowed money, and what interest rate moves might do to them. In this market, they find counterparties, cut deals, and take some of that fear off the table. This is the interest rate derivatives (IRD) market — which the RBI is now trying to deepen in India.

The big interest rate shift

Let’s zoom out, for a second: what is this “interest rate” we’re talking about, really?

It’s not the RBI’s repo rate. It’s the going rate at which banks borrow money in bulk. This happens at massive “money markets” where large institutions park their money, and others pick it up for their funding needs. If you’ve ever wondered where liquid funds put your money, for instance, this is where. The RBI signals where it wants these rates to be through its repo rate, but the actual rate is simply set by supply and demand in these markets.

That gives us an economy-wide “cost price” for money. If you want to give out a loan that steadily keeps you profitable, you can price it by adding a small margin to this — say “cost price + 2%”.

Only, there isn’t a single rate at which transactions happen. Money markets see millions of trades, each at a slightly different price. If you want to make this useful — say, you want to use the price on this market to set a rate for your loans — you need to condense those trades into a single “benchmark” rate.

How do you get there?

Not too long ago, we’d rely on a really rough metric — we’d poll a panel of major banks, asking them for estimates of what rate they could borrow money at for, let’s say, three months. Those quotes could then be processed to set a three-month “interbank offering rate” (IBOR). In India, for instance, we’ve often used the “Mumbai interbank offering rate”, or MIBOR. A lot of lending was pegged to this rate.

After the 2008 crisis, however, institutions began souring on the IBOR. Among other things, banks simply didn’t give each other three-month loans any more. The rates they quoted were, basically, a guess. Worse still, banks would try to manipulate these for a quick buck. We needed a new, more trustworthy benchmark.

For that, many countries started doing heavy data work on their money markets. The most liquid part of the money market was the market for overnight loans — where banks borrowed money for a single night, just to meet their regulatory requirements. These are practically risk-free transactions. When you charge interest here, you aren’t seeking any extra premium for the risk that someone might default. The asking rate, here, is the purest expression of the cost of money in an economy.

This rate — the risk-free rate or “RFR” — was an incredible way to construct a benchmark. It was clean, transparent, and based purely on data.

The RBI, for instance, has introduced a “Secured Overnight Rupee Rate”, or SORR, which is India’s risk-free rate for money.

The derivatives logic flips

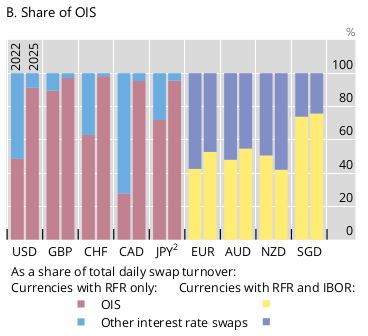

Over time, institutions started tying their lending to this transparent risk-free rate, instead of IBORs. Some countries, like the United States, phased IBORs out altogether. But elsewhere, too, they’re falling out of use.

This changed how most loans worked.

IBORs give you a forward-looking benchmark. A three-month MIBOR, for instance, told you what India’s banks expected to pay for money over the next three months. That number could be flawed, but it gave everyone certainty. Imagine, for instance, that you took a loan priced at the three-month MIBOR, plus 2%. Every quarter, the bank would set the exact amount you were expected to pay. On January 1, for instance, it would tell you something like “the three-month MIBOR is 5.2%, so, at the end of March, pay me interest at 7.2%.”

RFR-linked loans behave very differently. Imagine, for instance, that your loan is priced at SORR + 2%. At the end of every quarter, the bank calculates the compounded interest it would have paid, had it borrowed that money from the money markets every single night for the last three months. That gives the bank’s “cost price”. You then pay 2% more than that.

That number comes from past data, so nobody knows the rate in advance — you’ll only know what you owe the bank once that interest comes due. What used to be a single, forward-looking number became the combined outcome of 90 different tiny, daily moves.

With this, naturally, the derivative side-bets had to change — quite drastically.

In the old world of IBORs, your risk came in chunks. Once a quarter, there would be a great reset, and you didn’t want to get caught on the wrong side. So, you would try to lock-in a future interest rate for a particular date. You could enter into a contract saying, for instance, that “on April 1, no matter what the rates are, I want to pay 5.5%” and that would be it.

Cancelling out dozens of tiny, single-night changes is more complicated. Each new day is a potential surprise. To manage that, you need to constantly fine-tune and rebalance — through a mix of swaps, bonds and futures. Institutions try and give this headache away through derivatives called “Overnight Indexed Swaps”. In countries across the world, these have become the most traded interest rate derivatives today.

The hedge fund play

So far, we’ve seen the tame world of financial institutions trying to protect their downside. But several things are happening, at once, that create the conditions for a deceptively lucrative trade.

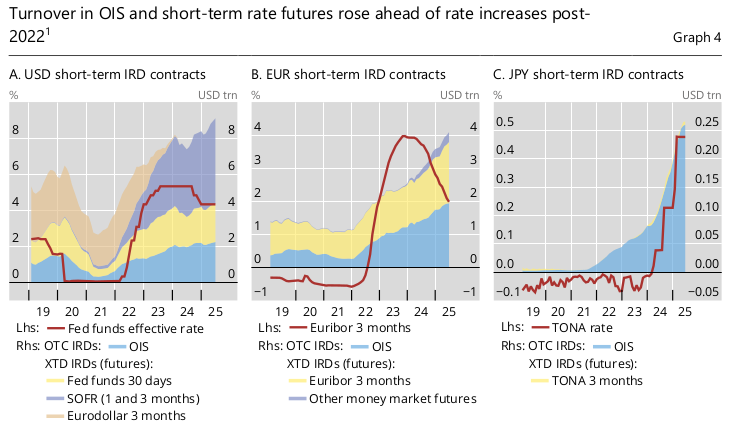

One, after hanging around zero for many years, in the post-COVID era, interest rates started rising across the developed world. As this happened, the markets’ old assumptions fell apart, and everyone rushed to hedge themselves.

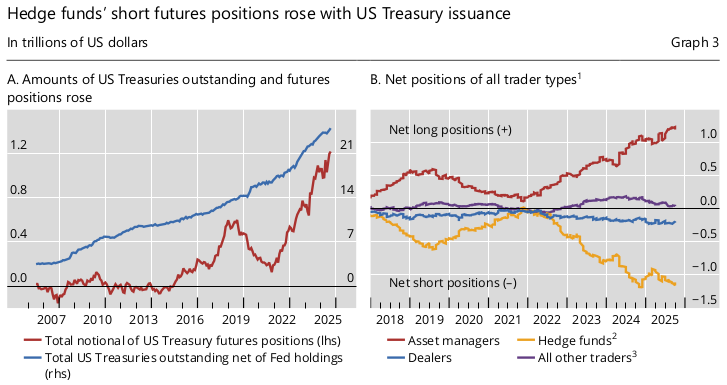

Two, anyone selling OIS contracts becomes exposed to constant, small fluctuations in interest rates. And so, dealers in those hedging contracts have to hedge their own risk. One way of doing so is to trade “bond futures”. In a sense, these let you take a side-bet on what the future price of a bond might be. Bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions, and so, these futures offset some of the risk these OIS contracts create.

Three, governments are running larger and larger deficits. Their central banks, too, are carrying out “quantitative tightening”. Both flood the markets with bonds. Regular banks can only buy so much of them — bonds bog down your balance sheet, and besides, banks have been bound by all sorts of regulatory constraints since the 2008 crisis.

Together, these do something weird. Actually owning bonds is now much harder than betting on their price. And so, if you’re willing to actually hold bonds, you get a tiny discount over the price that betting markets imply.

The difference is just a few basis points. But that tiny gap, itself, is an opportunity. Hedge funds use it to run what is called a “cash-future basis trade”. They borrow a lot of money, buy the cheaper instrument — the bond — sell the more expensive one — the future — and pocket the difference. That leverage allows them to turn that small gap into a big return.

This is a boring, mechanical trade with a sweet pay-off. It’s almost guaranteed to work. But there lies the rub. Our history with financial crises has taught us one thing: if you load too much debt on something that almost always works, there eventually comes a day when it doesn’t — and everything falls apart.

That, to the BIS, is a risk in the making.

India’s deepening market

India’s IRD markets, meanwhile, are in a very different stage — and we arguably have the opposite problem.

Advanced countries are dealing with extremely deep, highly liquid markets that are threatening to become over-financialised. A sharp change in rates or liquidity could unwind a lot of trades, creating stress that travels through their financial system.

Our market, in contrast, is shallow. Our exchange-traded market is practically non-existent. Most contracts for Rupee interest rate derivatives are settled in foreign countries. This means fewer leveraged trades, and less system-wide risk. But it also means that it’s harder for India’s financial institutions to hedge bona fide transactions.

Through its latest master directions, though, the RBI is trying to make that market scale. It has widened who can participate in this market, and what trades they can make. Instead of making banks check if every transaction legitimately tries to hedge against some sort of harm. It’s more willing to trust that entities in this market understand what they’re doing — without forcing all sorts of checks on them.

At the same time, it isn’t diluting all its guardrails. For instance, it specifically bans leveraged instruments, to avoid the sort of situation the BIS warns against.

Financial markets are meant to rearrange risk. In a shallow market, doing so is hard. In a deeper, more leveraged one, the re-arranged risk can itself become a problem. The RBI’s big challenge is whether it can thread the needle, balancing the two.

A primer on the auto ancillary business

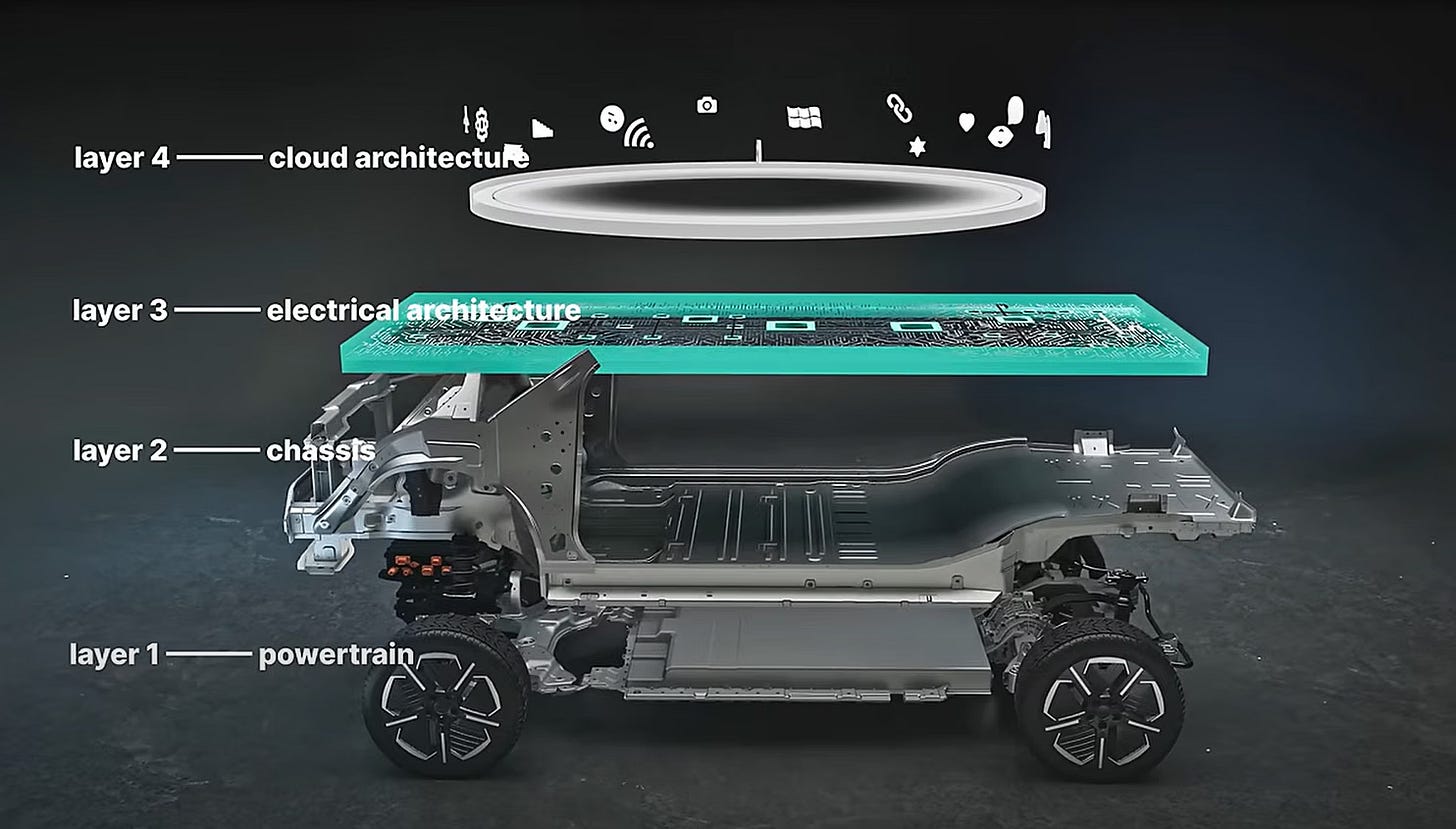

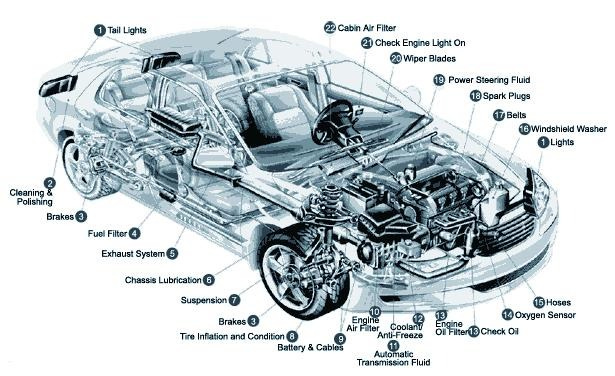

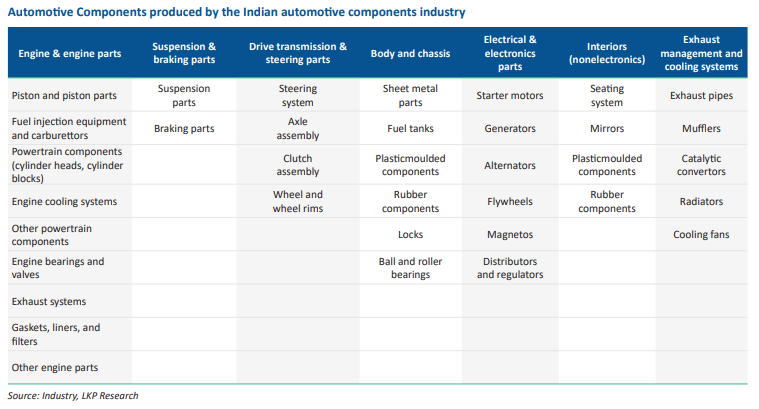

A car is an incredibly complex and detailed being. A typical car can comprise over 30,000 components, each with its own journey to the assembly line. Think wiring harnesses that carry electrical signals, ABS brakes and airbags that save lives, interiors, cameras, headlights, and so on.

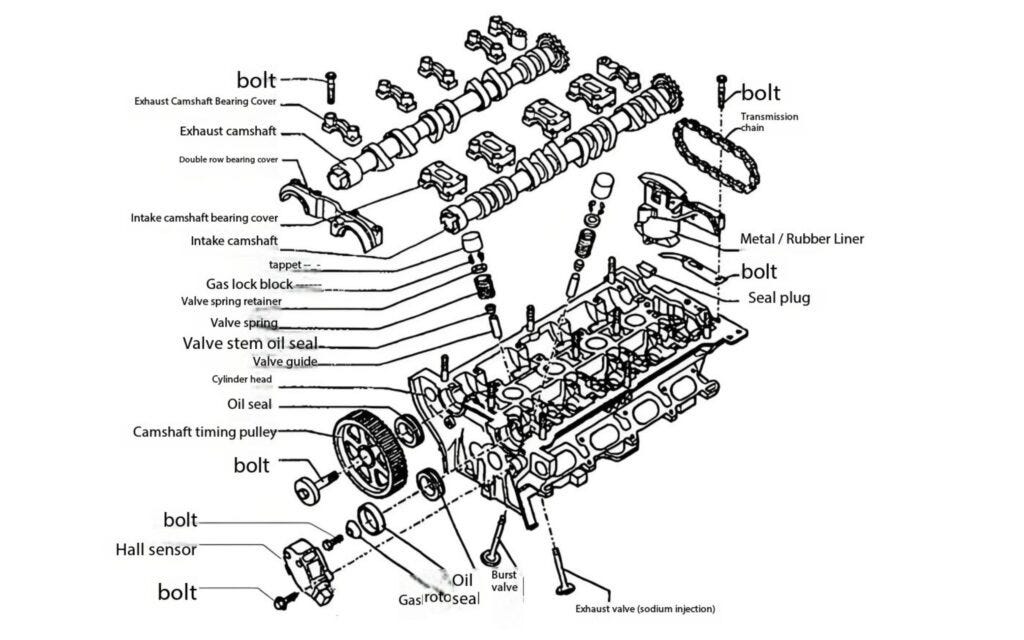

Some of these parts themselves are incredibly complicated — like a complete engine or powertrain, which themselves contain dozens of sub-components.

And original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) like Tata, Maruti, and Mahindra don’t build most of them in-house. Even an essential component like the engine, for instance, might be proprietary to the OEM, but its sub-components are likely sourced from somewhere else.

For these, automakers rely on a vast network of specialized auto ancillaries. These firms design, manufacture, and deliver all the little parts that go into your car — from fuel injectors to seat assemblies to wiring harnesses.

These fascinating entities have their own economics, value chains, and power dynamics. We couldn’t fit all of this into a single edition. So, consider this the first of a two-parter. This first piece is a primer on how the auto ancillary business model works. The second part will cover how Indian players are evolving, especially as EVs assume importance.

Let’s dive in.

A long courtship

The auto ancillary business operates on really long timelines, primarily as it is heavily tied to how auto OEMs design and develop cars.

See, OEMs usually don’t design individual cars from scratch each time. Instead, they build vehicle platforms — a common skeletal architecture that can underpin multiple models. These specify the layout of the chassis, the drivetrain, the suspension setup, and so on. Developing a new platform takes a lot of time, money, and R&D. But once the platform is designed, you can launch many specific car models on top of it.

For instance, one of Maruti Suzuki’s flagship platforms is the Heartect. With this base, it launched popular models like the Swift Dzire and the Baleno. Tata’s acti.ev platform, similarly, is the foundation of its EVs, like Harrier and Curvv.

Ancillaries get involved early on with the platform-building process. When an OEM has a platform design in mind with key specifications, it sends out a “request for information” (or RFI) to ancillaries. This is to check whether a supplier can design and mass-manufacture customized car parts as per the OEM’s needs.

Next, the OEM releases a request for quotations (RFQ), seeking bids from a shortlist of suppliers whose RFIs they were satisfied with. Here’s where the competition begins: suppliers have to give them a commercial quote on what they can make, how quickly, what risks they’re willing to take, and how much capex may be required.

The winner of this bidding process gets to co-develop components for the OEM platform. It effectively locks in a multi-year contract for the entire life of that platform — which could span many years and models. That is a huge win. If even one of those models is a big hit, it could bring in massive amounts of business.

But first, the supplier has to invest in capex before the start of production (SOP). All of this takes 3-4 years.

And then, the actual cars start getting mass-manufactured. The treadmill begins. For the next many years, the supplier has to deliver parts just-in-time to the OEM’s assembly plants, often just hours or days before they’re needed on the production line. OEMs usually don’t keep a strong inventory of car parts.

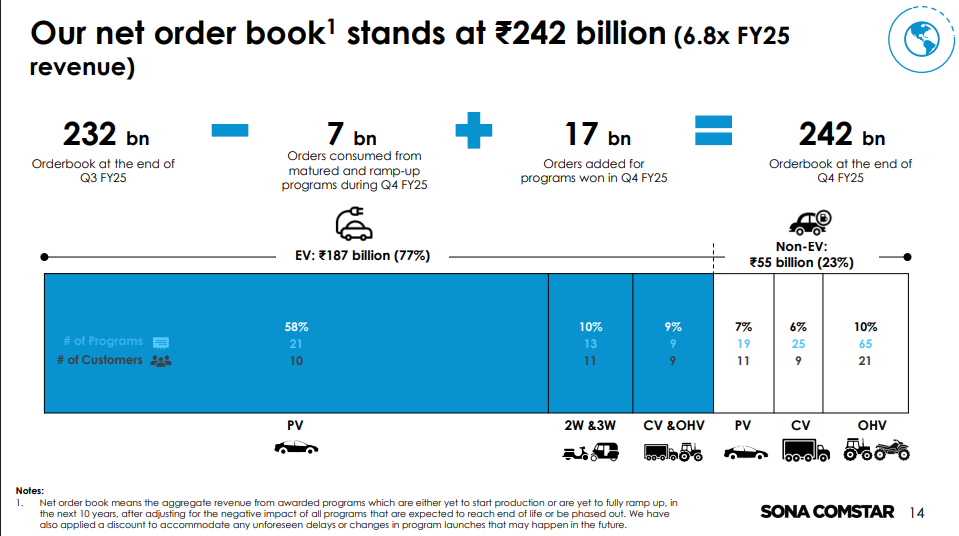

Essentially, any deal executes over a very long period of time. For this reason, suppliers often have order books that are multiple times greater than their revenue. Contracts won today that won’t generate meaningful revenue until when the models start getting sold at volume — which can take years. Sona Comstar’s total revenue in FY25, for instance, was over ₹35 billion. But their order book at the end FY25 was nearly 7 times that of revenue. This will only be realized over the next decade.

Once a supplier wins a platform, though, they become deeply entrenched. Switching suppliers mid-cycle is prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. It would require the OEM to re-tool, re-qualify, and re-test everything. This creates extreme stickiness.

In many ways, this resembles another industry we’ve covered before — passenger aircraft — although at a small, simpler scale.

Why carmakers don’t make their own parts

But why does this industry exist at all? If these parts are so critical, why don’t automakers just manufacture them in-house?

Turns out, they used to. In the mid-20th century, giants like Ford, GM, and even Tata Motors were vertically-integrated behemoths. Ford’s famous River Rouge complex was the extreme example — the company owned everything from raw iron ore and coal mines, down to the finished cars, and everything in between.

By the 2000s, though, the limitations of vertical integration became apparent. Almost every major automaker spun off or sold their parts divisions. Today, a huge chunk of a vehicle’s production value comes from external suppliers. The OEM’s role has become one of being the conductor of a vast orchestra of specialized suppliers.

Why? Because of the complexity involved.

Modern vehicle parts are extremely intricate, requiring everything from electronics, to specialized materials, to advanced safety systems, and more. With complexity, the expertise required for each component exploded. Every part would require its own R&D and manufacturing processes. It became impractical for a single OEM to invest resources into making thousands of different parts, instead of focusing on what they were good at: making the final car.

Meanwhile, the economics of being an independent car part supplier made more sense. A supplier could serve multiple OEMs at once. A company making brake systems or automotive semiconductors could achieve volumes no single carmaker could match on their own. Suppliers could then invest heavily in specialized manufacturing and automation, spreading those costs across many customers.

Marginalizing the margins

This outsourcing model made carmakers more efficient. However, their risks didn’t disappear — they simply got transferred to suppliers. Auto ancillary firms operate in a high-volume, low-margin paradigm with very specific — and often punishing — economics. Let’s break down why.

Payment cycles

Let’s start with how they’re paid.

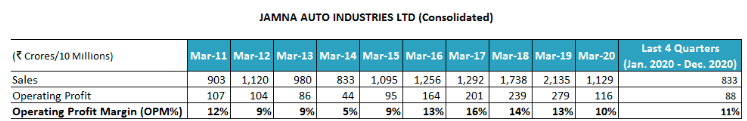

The car parts business is heavily tied to how many cars get sold in the economy — when sales are good, profitability is high. When they aren’t, margins tank. Here’s a table from Dr Vijay Malik’s blog that shows the swing.

Suppliers only get paid when parts are delivered. Moreover, payments come with a lag — typically 30 to 90 days after delivery. But their costs — particularly capex — are heavily front-loaded. Winning a new contract requires huge upfront investment in R&D, prototyping, and dedicated production tooling, often starting two to three years before production begins. If a vehicle sells poorly, the supplier may never recoup those costs.

Low margins

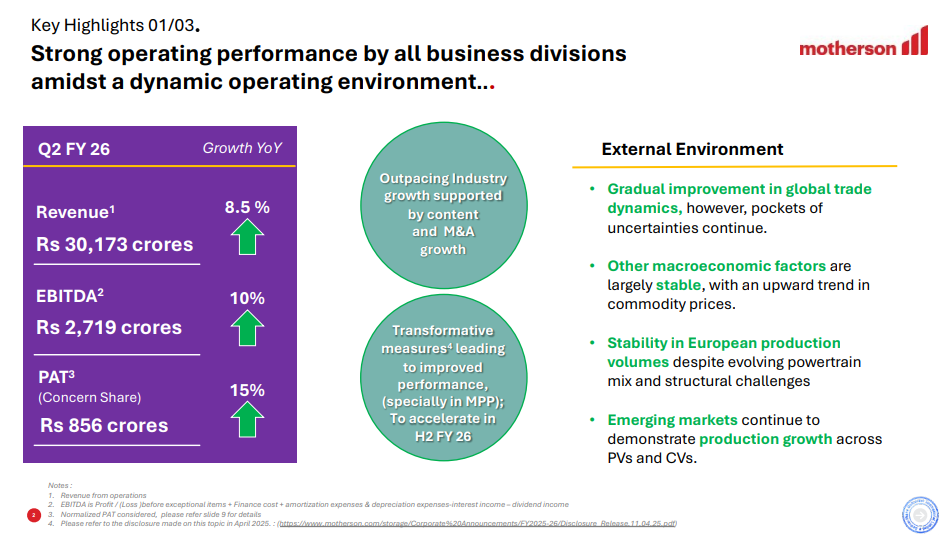

The auto ancillary business is known for being a low-margin business. For instance, this quarter, the PAT margins of Samvardhana Motherson, the largest Indian ancillary, were barely 3%. And this was a good quarter in their words. This is the industry norm, where even the largest companies get by with 5-8% net margins.

Here’s the thing: the supplier contract is awarded through competitive bidding that drives margins to the bare minimum. On top of that, a customized, platform-specific part might not fit another, so the supplier can’t simply sell it elsewhere if the price isn’t favorable.

But more than that, OEMs simply have a lot of power, and can dictate the terms of a contract. The price is often locked in over the long-term, and won’t be subject to changes that can’t be foreseen. Most contracts also include annual cost-reduction clauses, where OEMs expect part prices to fall 1-3% every year because they expect the supplier to become more efficient with practice.

The contract also includes extremely tight delivery obligations. Just-in-time manufacturing means parts must arrive at the assembly plant in the exact order and quantity needed, often within hours. Automakers levy penalties on ancillaries if their requirements are not met on time. The burden of carrying inventory and ensuring timely logistics — and hence the costs — are entirely on ancillaries.

At the other end, ancillaries are exposed to swings in the price of raw materials. In fact, procuring steel and aluminium makes up over half of the costs of an ancillary. Meanwhile, OEMs typically allow only partial pass-through of cost increases, and often with significant lag. When commodity prices spike, margins could get crushed.

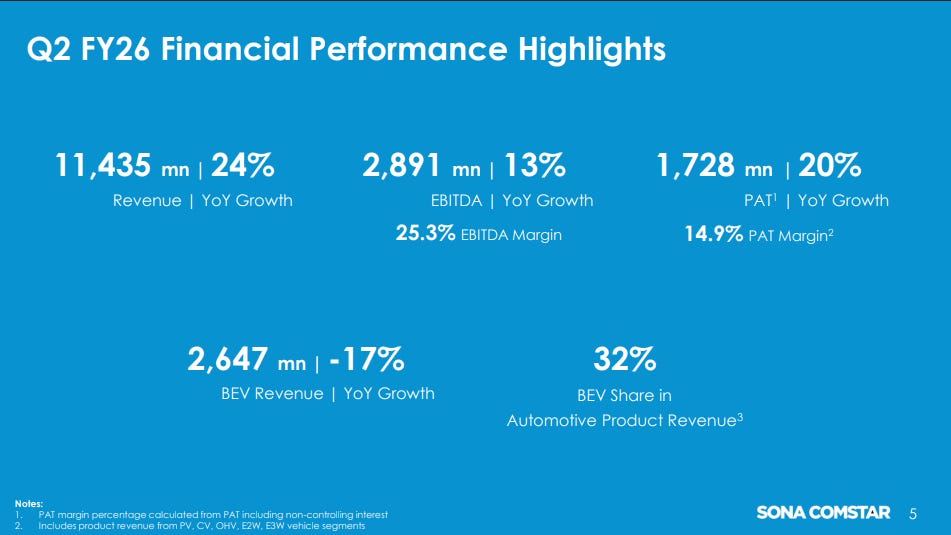

That said, these dynamics vary between parts. Makers of commoditized parts suffer extremely low margins — Motherson, for instance, is a market leader in wire harnesses, which are very common. But Sona Comstar, for instance, makes traction motors for EVs, which require far more technical know-how. That gave them ~15% PAT margin this quarter. What also helps is if an ancillary owns IP for a certain product or service, giving them negotiating power with automakers.

So how do you make money in this business? Ideally, the best pathway to profit for ancillaries is scale and high capacity utilization. Yet, this has a huge downside — scale without capacity utilization can be suicidal. Fixed costs — machinery, tooling, plant overhead — are enormous. And revenues come years after they put down that capex. In a downturn, those same fixed costs become a massive drag.

How suppliers survive

Given these brutal economics, how do auto component makers find cushions?

One major strategy is aftermarket sales. The market for replacement parts, which are sold to authorized dealers or independent mechanics, operates on different dynamics. Demand, here, is tied to the existing vehicle population, and not new car sales — making it more stable. And you get pricing power.

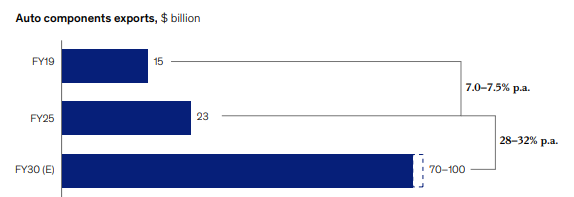

Another cushion is exports. Selling to overseas markets can yield better margins. The Indian ancillary market, currently, is mostly domestic, but export volumes are growing steadily, with North America and Europe emerging as key destinations. Export business also helps hedge against domestic downturns.

A third, important one is diversification.The most successful suppliers avoid over-dependence on any single platform, OEM, or product line. They supply across passenger vehicles, commercial vehicles, and two-wheelers. Some even expand into adjacent industries like aerospace or industrial equipment. For instance, Bharat Forge, one of the largest axle beam makers in the world, has been doubling down on defense systems like drones and artillery.

But, of course, the most sure-shot way is moving up the value chain and making more advanced, premium parts. We’ll get there in Part 2.

Inflection point

That, more or less, is a wrap on how the business works.

But there’s a lot more to explore. Right now, this model is getting shaped by various forces. The most important of those is the rise of EVs, which is reshaping which car parts are necessary. Meanwhile, the global supply chain is fragmenting, creating opportunities for Indian suppliers. These companies are also undergoing their own wave of premiumization.

For all of this, tune in the next time.

Tidbits

Mexico Tariff Hike Hits Indian Auto Exports: Mexico’s decision to raise car import tariffs from 20% to 50% will impact nearly $1 billion in Indian auto exports, with Volkswagen, Hyundai, Nissan, and Maruti Suzuki among the hardest hit despite industry lobbying efforts.

Source: ReutersOracle Slumps 13% on AI Spending Concerns: Oracle shares fell 13%, wiping out over $90 billion in market value, after weak forecasts and plans to spend $15 billion more than expected on AI infrastructure raised concerns about returns on its heavy investments.

Source : ReutersNovo Nordisk Appeals Semaglutide Export Ruling: Novo Nordisk has appealed a Delhi High Court order allowing Dr Reddy’s to manufacture and export semaglutide (Ozempic) to countries where Novo lacks patents, while domestic sales remain barred until March 2026.

Source: BS

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Manie.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

An excellent and highly informative article on IRD. I was not quite aware that such a thing exists in background. Thanks for upgrading my knowledge once again 👍

Can't wait for the Part 2 on auto parts business! Thank you