ICICI Pru AMC's IPO: A window Into India’s MF boom

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

ICICI’s Mutual Funds arm could soon IPO!

UPI and the magic of interoperability

ICICI’s Mutual Funds arm could soon IPO!

Fifteen years ago, mutual funds in India were a footnote in most people’s portfolios.

Your neighbourhood LIC agent was the closest thing you had to a financial advisor. ULIPs seemed like excellent savings products — "insurance with stock market returns" — and equity investing was meant for gamblers. But in the last decade or so, a combination of regulatory prodding, a rising middle class, and relentless marketing (oh, and fintech companies like us!) ensured that mutual funds would become a strong pillar of the Indian retail investing ecosystem.

Yet, even today, there are miles for the industry to go. Of more than 70 crore PAN holders in the country, just around 5 crore are mutual fund investors. And that counts folios, not unique individuals. The actual number of Indian people who invest in mutual funds is closer to 3.8 crore — barely 5% of our population.

For every Indian the industry has reached, there are another 19 it hasn’t.

That’s the context in which ICICI Prudential AMC, one of India’s largest mutual fund houses, has decided to IPO. This comes when the business model of active fund management is being reshaped by regulation, passive funds are getting commoditised, and digital platforms are turning things on their head. The total pie, on the other hand, is expanding.

First, the basics. We don’t know what the price of the IPO will be. Or when it’ll be open. All we know at the moment is that this will be a 100% Offer for Sale (OFS) — meaning that existing shareholders are selling their stake in the company.

But what we’re interested in is the rest of their DRHP. See, this is a goldmine to understand the mutual fund business, this moment in its history, and the fate of the industry.

The business model

The AMC business, at its bare bones, is this: you take other people’s money, invest it for them, and charge them a small fee each year.

One of the most important details, in such a business, is its ‘AUM’. A company’s AUM, or ‘Assets under Management’, is the total money it currently manages for its customers. What the company earns is a function of its AUM. As of Q4 FY25, ICICI Prudential AMC’s average mutual fund AUM stood at ₹61.3 lakh crore.

But the AUM alone doesn’t tell you much. The nature of that AUM is as important — because different categories of mutual funds have different ‘expense ratios’, i.e. they earn wildly different fees.

Here's the split for ICICI Pru AMC:

More than half of its AUM — roughly 55% — is in equity-oriented schemes.

Debt-oriented schemes come next, with ~20%.

Around 8% sits in liquid and overnight funds.

Passive and other schemes make up another 15%.

Why is this important? See, there are different costs to managing different kinds of schemes. They take different amounts of attention and research, trading works differently, and so on. And so, AMCs charge differently for them.

Equity funds typically hjave total expense ratios in the range of 1.5–2.0% for regular plans, and 0.5–1.0% in direct plans. Debt funds earn closer to 0.25–0.75%. ETFs and passive products earn just 5–20 basis points. So, two funds that manage the same amount of money could contribute very different revenues to the AMC.

ICICI Pru has a relatively high equity mix. That makes it a higher-margin AMC than its peers, who are more debt-heavy. Even within equity, over 82% sits in actively managed schemes — which earn much better margins than passive.

How ICICI Pru AMC is positioned among its peers

As per CRISIL, ICICI Pru AMC manages the most money actively among its peers, with a 13.3% share of the active fund market as of March 2025. It also draws the largest AUMs of any fund house from retail investors. That’s a big advantage: retail equity tends to get better margins than corporates, and investors stick around for longer.

There are bigger AMCs still, however. SBI Mutual Fund has a larger overall AUM. It benefits from large mandates that come in from government organisations like Employee Provident Fund (EPFO) and PSUs — giving them a lot of money to manage, although they make very little on it. HDFC AMC, meanwhile, is more profitable, despite managing less money — because its AUM mix is even more skewed toward high-fee equity funds, while their operating costs are tighter.

There’s also the matter of where these funds draw their customers from.

ICICI Pru has been particularly good at acquiring customers through digital channels, and from the ‘B30’ (or ‘Beyond 30’) cities – locations outside India’s top 30 cities (T30). This is still an emerging market for mutual funds. This group is also the least keen on passive funds.

The revenue picture

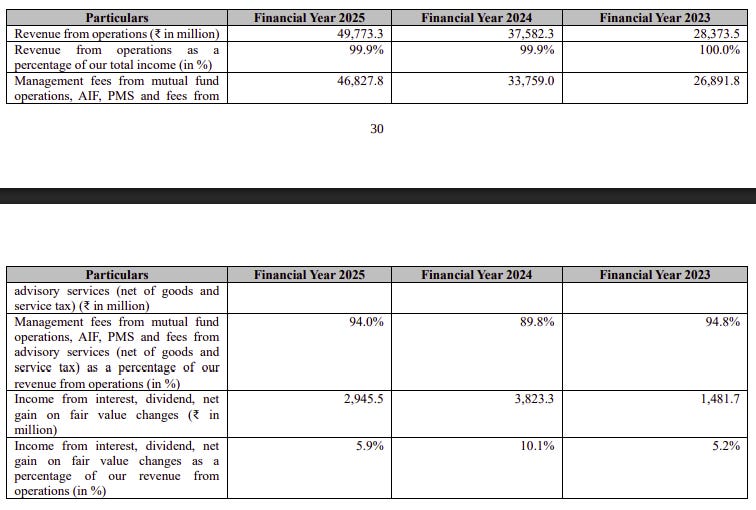

In FY25, the company earned ₹4,977 crore in revenue from operations.

More than half of that — ₹2,651 crore — came to the company as profit after tax. That means its “net margins” are comfortably north of 50%. On top of that, the company has almost zero working capital needs and negligible capex. Its profits, that is, are all free cash.

These are not normal numbers for financial services businesses. Banks have scale, but they’re bogged down by credit costs and capital requirements. Insurers need decades to hit this level of profitability.

This is what sets an AMC like ICICI Pru apart. Once it achieves enough scale, these businesses are so asset-light that all their fixed costs can be spread very efficiently. Everything else is profit. They basically turn into cash cows, once they grow big enough. This is a business that thrives on scale.

This revenue, in fact, is growing rapidly. It went from ₹2,837 crore in FY23, to ₹3,758 crore in FY24, to nearly ₹5,000 crore in FY25. There are two levers behind this stupendous growth – the company is managing more with each passing year, and is also earning better fees on each rupee managed.

ICICI Prudential AMC has other business lines too. It runs Portfolio Management Services (PMS) and Alternative Investment Funds (AIFs). These are bespoke, often high-ticket offerings aimed at HNIs and institutional clients. But they are a very small part of the revenue pie: they made just ₹49 crore of total revenue in FY25.

But if less than 60% of that is profit, what does the company spend on?

A good chunk goes towards employee expenses. That’s intuitive: this is basically a business built around hiring extremely smart (and well-paid) money managers.

They also spend a hefty amount on acquiring customers — especially for regular plans sold via banks and distributors. As direct plans and online onboarding rise, they’re also having to put in more money into their technology.

A heavily regulated industry

There’s one major risk to such a business: this is an industry that lives and dies on SEBI’s word.

Over the last 15 years or so, SEBI has reshaped the business.

In 2009, it scrapped entry loads. AMCs could no longer charge investors an upfront fee, using it to pay off distributors. That was a 2.25% hidden charge — a huge chunk of the returns investors were seeking. When this was scrapped, AMCs had to pay distributors from their own P&L, reducing profitability.

Then, in 2013, it mandated ‘Direct Plans’. This was a separate class of mutual fund units that skipped commissions — giving investors a cheaper version of the same fund. This was great for informed investors, but squeezed margins further.

That’s not all. In 2018-19, SEBI rationalised their expense ratios, adding caps based on scheme size. In 2023, it suggested a model where AMCs can charge higher fees only if they consistently beat their benchmarks. And so on.

Each of these interventions has been good for mutual fund investors. But if you’re evaluating an AMC itself as an investment, this is a variable you have to account for.

The rise of passive mutual funds

Here’s another important variable: Over the last five years, passive investing has exploded in India.

What started with a few ETFs is now a full-blown wave. Passive funds now command well over ₹10 lakh crore — around 20% of industry-wide assets. This is all very recent. Last year, over 50% of the net inflows went into passive strategies.

This is great for investors.

But passive funds carry razor-thin fees — often just 5–15 basis points. Active equity funds, on the other hand, could earn as much as 2% — anywhere up to 40x as much. To AMCs, therefore, the shift to passive funds is a hit on their fees. ICICI Pru, heavily skewed toward active equity, is particularly vulnerable to such a trend.

Increasingly, they’ll have to move to low-margin index products to stay relevant with digital-first, cost-conscious investors — even though that’ll hit their own revenues.

The risks

There are other vulnerabilities for the business as well:

Market-linked revenue:

The AMC business looks great when the markets are hot. When they fall, though, everything starts to break.

For one, when markets fall, their assets become cheaper — and the ‘AUM’ shrinks. And because their revenue is tied to the AUM, AMCs earn less money.

But it doesn’t stop there. When markets turn, investors get cautious. New money stops coming in. Distributors find it harder to convince investors to commit. Even loyal clients start sitting on the sidelines. Meanwhile, people panic, and withdraw their money.

Meanwhile, costs stay the same.

Talent churn

This is an industry that relies on hiring a few very bright people. And those people are in high demand. The top 20 fund managers matter more than you think. If they leave, it can impact flows and performance.

(On the topic of top talent, by the way, we’ve interviewed S Naren, the company’s CIO. Check it out here!)

The bottom line

ICICI Pru AMC’s upcoming IPO is a snapshot of an industry at an inflection point.

With high profitability, a dominant active equity mix, and strong digital distribution, ICICI Pru looks like a cash-generating machine today. But at the same time, the mutual fund business is changing rapidly. The company’s DRHP offers a rare, detailed look at this evolving landscape.

If you’re wondering whether to invest in the company, you shouldn’t just look at what the AMC earns now — but how it will hold up as the rules, returns, and retail expectations continue to change.

UPI and the magic of interoperability

We spend a lot of time on this newsletter talking about parts of our economy that don’t work. But that isn’t, of course, all our economy is made of. There are pockets of excellence where we’re world-class — or even lead the world.

A recent IMF paper gave us the chance to look deeply into one such sphere — digital payments, or more specifically, the Unified Payments Interface (UPI).

A lot of the world is trying to crack digital payments. It’s easy to see why. If you’re reading this, there’s a good chance you’ve seen the benefits of a thriving digital payment system first hand. The UPI made it infinitely easier to work with digital apps. Transaction costs almost disappeared. You no longer feel the need to carry cash around.

But despite these benefits, many countries simply haven’t managed anything nearly as good.

On the surface, this sort of system might seem easy enough to create. If you have a smartphone and a bank account, how hard could it be to build everything else? Turns out, it’s extremely hard. And yet, we’ve done it. How? That’s what the IMF is trying to explore.

The rise of the UPI

For context, let’s start with all the stuff you probably already know.

For around half a decade before the UPI came into its own, India already had an instant payment mechanism: the Immediate Payment Service, or IMPS. This system could transfer funds between banks in real-time.

There were other ways of transferring money that came before: like the NEFT and RTGS systems. But they weren’t nearly as elegant. They couldn’t work in real time: it would take hours for money to move between bank accounts, and would only work during certain hours.

IMPS emerged as “always on” rails between banks, that would service any retail transaction no matter when it was made. It was to build out these rails that the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) — the entity behind UPI — was first created, back in 2009. Slowly, different banks joined this system, and by 2015, it had come into its own as a real-time payment system. It was still miniscule in scale, though. In 2015, IMPS managed nearly 200 million transactions: impressive, and yet a fraction of what goes through the system today.

The UPI grew out of this system.

It was built on top of the IMPS. The rails created for IMPS became its clearing and settlement layer: the same links actually moved money between banks. But the UPI made these rails infinitely easier to use. It stripped away the friction of account numbers and IFSC codes. In its place, it gave everyone easy-to-use “Virtual Payment Addresses”. And it gave anyone the ability to build out “front-ends,” through which anyone could access these rails. People no longer had to rely on clunky bank websites to send money.

Of course, ease-of-use alone wasn’t enough to create a system of the sheer scale of the UPI.

At the beginning, there were many serious barriers to UPI adoption. For such a system to work, Indians needed to have bank accounts and smartphones. And there had to be a way of verifying the identity of people making transactions, so that you could avoid fraud without having to individually verify each person’s identity whenever a transaction was made.

These were complex problems. Yet, they were all solved. The Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana brought bank accounts to millions of people who were previously just used cash. Aadhar solved the problem of authentication. And the entry of Jio brought rock-bottom mobile data to everyone.

This created the base conditions which made it possible for the network to grow. But it needed a catalyst.

That catalyst was a severe, system-wide shock: demonetisation. In one stroke, overnight, most of the currency people held became worthless. As hour-long queues sprung up around ATMs that would routinely run out of cash, people needed an alternative immediately. For a country that ran on cash, suddenly, people were willing to try whatever option was available to them. Millions tried digital payments for the first time. And it was smooth. UPI stuck.

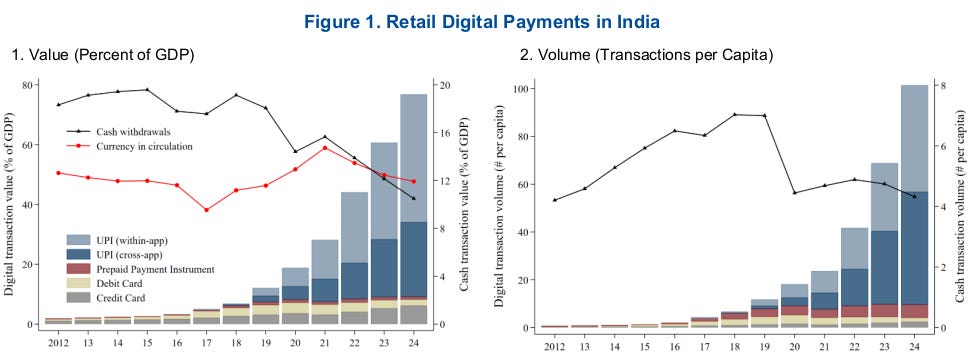

Today, the UPI is practically omnipresent in India. It is a sprawling ecosystem that covers 600+ banks. More than 200 apps run on the system, processing 18+ billion transactions every month. Cash payments, once the backbone of our economy, are actually declining.

There were, in short, many reasons behind the UPI becoming what it is. The system is a product of our peculiar history. But to the IMF, there’s a secret sauce that really sets it apart. It’s the one fundamental feature that ensures that the UPI isn’t just a popular system, but a world-beating one: inter-operability.

The alternative: Getting trapped in an ecosystem

The UPI, you see, isn’t the only digital payments system in the world. But it’s just a great one.

We Indians are practically spoiled by how seamless our payments experience is. There’s a distinct lack of friction in our online payments: it just works. That’s not something to take for granted.

Many systems abroad are “closed loop” systems. Here, everyone — the person making a payment, the person getting the money, and the system that stitches them together — have to belong to the same network.

If you want to know what that feels like, think of how any of your other apps run: if you’re booking an Uber, for instance, you, your taxi driver and the app — are all bundled into a single network. You can’t book a Rapido using your Uber app. In many countries, payments practically work the same way.

These systems create “network effects”. Any product becomes more useful as more people use it. But that also means they can become exclusionary. If the people you transact with are all on one network, you’re forced to join it. You’ll find it hard to get out, while any other system will find it much harder to get your business. Meanwhile, if you come across a shop that runs on some other network, you’ll have to download a whole new app, or just pay in cash.

Who you can pay through your phone, essentially, will depend on what app you have.

But there’s another possibility: interoperable systems. Interoperability cuts through these closed loops. It lets people choose whatever app they want, with the promise that it’ll work seamlessly with users of any other app. It’s a little like email, in fact: you might use a Gmail account, for instance, but that doesn’t mean you can’t to talk someone who uses any other provider.

The magic of inter-operability

Making such a system is harder than it looks, because you need to ensure that everyone involved is on the same page on a range of matters. To the IMF, there are three things that you need to really call a system inter-operable.

Technical compatibility: First, there’s a matter of the wiring. You have to ensure that different apps, banks, or platforms can connect and send messages to each other. On UPI, every app and bank talks through a shared NPCI protocol — that everyone else uses as well.

Semantic compatibility: The ability to talk to each other isn’t enough. Just because two systems can exchange messages doesn’t mean they interpret them the same way. You need to ensure that if one app says “₹100 transfer” or “transaction declined: insufficient funds,” the receiving system understands it exactly the same way. UPI works because the meanings of every request, response, and failure code is precisely defined and universally followed.

Business compatibility: On top of this, though, different entities need to agree on the rules of the game. They need to agree on who is responsible for what, who pays for what, and how disputes or settlements are resolved. For UPI, NPCI helped enforce these terms across hundreds of banks and fintechs.

If any of these fail, things fall through the cracks. You can no longer guarantee that your payments will go through. The system will turn unreliable, friction will crop up, and people will exit.

If you get everything right, though — as the UPI did — you get to enjoy a product that’s genuinely superior. This is the crux of what the IMF found.

There were some benefits that you directly feel.

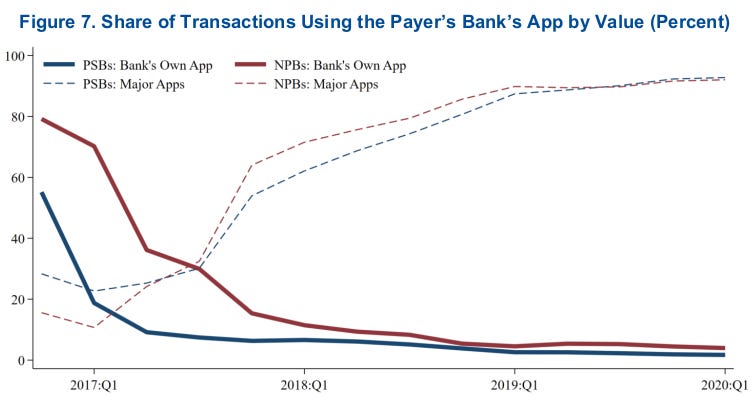

Interoperability gives you a real choice. Remember the early days of UPI? Most people started with their own bank's UPI app. Initially, in fact, over half of all transactions happened through people's own bank apps. After all, these were familiar and trusted.

If these were anything like other tech products, people would soon get locked into an app, and using anything else would be a pain. But that's where interoperability shines: once people got comfortable with the UPI, you could switch to a better app in a couple of minutes. Slowly, users migrated to specialised fintech apps — like PhonePe or Google Pay — which offered better features, rewards, or reliability. It was so easy to move, in fact, that an app with 1% fewer transaction failures would see 4% more usage the very next quarter. In other words, it was easy for people to vote with their fingers.

Beyond that, though, came a range of indirect benefits.

For one, it forced everyone to up their game. If users can abandon your app tomorrow, you can't get complacent. You can’t count on just locking them in. The IMF found that top apps dramatically reduced their failure rates even as transaction volumes exploded.

Meanwhile, new players didn’t find the market impossible to enter. They could come into the game by targeting specific niches. PhonePe, for instance, began by catering exclusively to retail customers, before moving on to merchants. BharatPe, on the other hand, began with a merchant-first approach. Companies began innovating with ideas like soundboxes, which would track all payments they received. By letting many businesses plug into the same network, the overall ecosystem grew in a way that close-loop ones simply would not.

This isn’t just a theory. The superiority of UPI is clear from how people took to it.

Consider this: back when digital payments were new — when demonetisation hit in November 2016 — people flocked to both UPI and closed-loop wallet apps (like a PayTM wallet). But once cash came back a few months later, the closed-loop systems plateaued. The UPI, meanwhile, tripled in size. The ability to pay across apps, clearly, was something everyone wanted.

The IMF, in fact, looks at a specific closed-loop provider that was forced to join UPI (possible PayTM, but we aren’t sure — the paper doesn’t say). The switch worked better than they would have hoped, though. In districts where the app was popular, as soon as it moved to the UPI, the entire district suddenly saw digital payments jump up by 8 rupees per person per month. As soon as they moved to an inter-operable system, new money suddenly flooded in.

The freedom to choose, it seems, leaves everyone better off.

Will interoperability survive?

Hidden in the IMF report, though, is a warning. Success can breed its own problems.

Today, just two apps — PhonePe and Google Pay — control over 85% of UPI transactions. Half of all UPI payments happen between people using the same app. People, it seems, are starting to cluster. This clustering seems to be happening on regional lines: with different apps dominating different parts of India.

Such dominance, if misused, could become a threat. The IMF warns that an unprincipled player could find ways to lock users in — they could offer proprietary app-specific features, or bundle in services like lending or insurance, or do something else that makes people reluctant to move to another app. For instance, early on, the RBI had to step in and stop companies from issuing proprietary QR codes, which would only let people pay with their specific app. This was calculated to break the system’s interoperability.

It’s certainly not the last. Eternal vigilance is the price of an open system.

India has one of the best payment systems in the world. The only threat is that we forget why it worked.

Tidbits

We reported earlier how Ola Electric saw a shocking reversal in Q4 FY25, with revenues crashing 62% and losses ballooning.

The Q1 FY26 results are out and, while losses are still high, there’s a faint glimmer of operational improvement.

The company posted a net loss of ₹428 crore, higher than the ₹347 crore loss in Q1 last year, but an improvement over ₹870 crore in Q4. Revenues, too, are up sequentially to ₹828 crore, though still down nearly 50% YoY.

Source: MintEarlier last week, Jane Street was banned for allegedly manipulating expiry-day index options.

Now, there’s an update.

The US-based firm deposited ₹4,843.5 crore into an escrow account on July 11, fulfilling SEBI’s conditions to lift the ban. Trading can now resume — but with a caveat: the flagged strategy remains off-limits.

Source: Business StandardWe are absolutely fascinated by quick commerce and have covered it multiple times, including Zomato’s shift in priority towards Blinkit.

Now, Blinkit is shifting to an inventory-led model starting September 1, 2025, where it will directly purchase products from sellers instead of merely storing them. This move aims to streamline operations and comply with Indian regulations on foreign ownership in online marketplaces.

Source: Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉