Hyundai wants to ride the bull run

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and video on YouTube.

You can also listen to The Daily Brief in Hindi.

Today on The Daily Brief:

Hyundai wants to ride the bull run

The great Indian promoter sell-off

The steel industry is stuck between a rock and a hard place

Hyundai wants to ride the bull run

Hyundai Motor India, the country’s second-largest carmaker, is gearing up for a massive ₹25,000 crore IPO. To put that in perspective, this could be India’s biggest IPO ever—even bigger than LIC’s ₹21,000 crore listing or Paytm’s ₹18,000 crore offering. SEBI has already given its approval, so now it’s up to Hyundai to decide when to launch. The goal? Hyundai aims to highlight the value of its Indian business and boost its market visibility through this Offer for Sale (OFS), with the South Korean parent company planning to sell off 17.5% of its stake.

But what makes this IPO so interesting isn’t just its size—it’s Hyundai’s role in the Indian market. Hyundai doesn’t just stand alone; it also owns about 34% of Kia Motors, which has quickly become India’s fifth-largest carmaker. Together, Hyundai and Kia hold a significant chunk of the market, sharing supply chains and strategies to stay competitive.

Let’s take a closer look at Hyundai’s position. In FY23, Hyundai Motor India’s revenues jumped to around ₹60,300 crore, up from ₹47,300 crore the previous year—a solid 27% increase. The company controls almost 15% of the overall passenger vehicle market, second to Maruti Suzuki’s 41%. Maruti’s dominance is clear, but Hyundai has carved out its own space, which makes things really interesting.

India’s car market is still quite underdeveloped. As of FY24, there are only 26 cars for every 1,000 people in India. Compare that to 594 per 1,000 in the US or 183 per 1,000 in China, and you see the huge growth potential. As incomes rise, there’s plenty of room for Hyundai to grow.

Hyundai sets itself apart with a different approach. While Maruti Suzuki focuses on high volumes, especially in the budget segment, Hyundai has taken a more premium route. In FY23, Hyundai’s average selling price was around ₹7.7 lakh, well above the industry average of ₹6.59 lakh. Hyundai’s focus on mid-size and premium vehicles like the Creta, Alcazar, and Venue gives it a profitability edge, thanks to the higher margins on these models.

Tata Motors, another key player, holds about 14% of the passenger vehicle market with popular models like the Nexon EV and SUVs like the Punch and Harrier. But Hyundai’s broader portfolio, especially its premium SUVs, keeps it ahead in terms of average selling price and market share.

SUVs are where the action is—they now make up over 45% of all passenger vehicles sold in India, and Hyundai controls nearly 20% of that market. Maruti Suzuki, despite leading in other areas, has struggled with models like the Brezza in the SUV space. Hyundai, on the other hand, has thrived by riding the demand wave for premium SUVs, which are increasingly popular with India’s growing middle class.

Looking ahead, India is slowly shifting toward electric vehicles (EVs), and Hyundai is gearing up for this change. EVs made up just 2% of total vehicle sales in FY23, but government policies like FAME II and the PM eDrive scheme are expected to boost adoption. However, these policies are now focused on two-wheelers, three-wheelers, and public transport rather than electric cars. The reason seems to be that EV cars are getting close to competing with traditional vehicles in terms of cost, so subsidies might not be necessary.

Still, Hyundai is pushing forward in the EV market. It launched the Kona Electric in 2019 and recently introduced the Ioniq 5, a premium electric SUV. And there’s more to come—by 2025, Hyundai plans to roll out the Creta EV, along with a mix of premium and affordable EVs to suit different customer needs. They’re also working on localizing EV component production, especially batteries, which will help cut costs and improve margins, giving them a better shot at competing with Tata Motors, the current EV leader.

Another big move is Hyundai’s recent acquisition of General Motors’ Talegaon plant, which will help boost production capacity. Once operational, this plant will push Hyundai’s production in India to over 10 lakh units annually. This isn’t just about meeting domestic demand—it’s also about ramping up exports, making India a key manufacturing hub for Hyundai’s global operations.

Overall, Hyundai Motor India’s IPO could be a game-changer, not just for the company but for the entire Indian auto market. With its lead in the SUV segment, a solid EV strategy, and growing exports, Hyundai is setting itself up for long-term growth in one of the world’s fastest-growing car markets. This IPO isn’t just a financial move—it’s a glimpse into where the future of the Indian automotive industry might be headed.

The great Indian promoter sell-off

Lately, promoters of Indian companies—the founders and key insiders—have been offloading their stakes in a big way. In 2024 alone, they’ve sold shares worth ₹1 lakh crore, the highest in the past five years. And if we look back a bit further, since April 2022, that figure jumps to ₹4.42 lakh crore!

We’re seeing a similar trend in the IPO market. Over the last 15 months, there have been 91 IPOs, but here’s the catch: 61% of the money raised wasn’t new investment going into the businesses. Instead, it was insiders choosing to cash out.

So, it begs the question: Why are promoters selling?

Promoters know their companies better than anyone else. So when they sell a large chunk of their stake, it makes investors stop and think: Are they seeing something that the rest of us aren’t? Is there trouble brewing under the surface?

The reality, though, isn’t always a red flag. Most of the time, it’s about timing. The markets have been on a good run lately, and companies are enjoying high valuations. For promoters, this is just a great time to cash in on some of their gains and cut down their holdings. It’s more of a strategic move than a sign of trouble.

But if promoters are selling, who’s buying?

Domestic mutual funds are stepping up as big buyers. So far this year, they’ve pumped ₹2.4 lakh crore into the stock market, bringing their total net inflows to ₹5 lakh crore since April 2022 through equity mutual funds. A big chunk of this comes from Systematic Investment Plans (SIPs), where small, regular investments have more than doubled in the last three years.

And it’s not just mutual funds jumping in—retail investors are becoming more active buyers too. This is a big shift because, between 2012 and 2019, retail investors were usually net sellers. But since 2020, they’ve flipped the script and have been consistently buying, with their involvement only growing.

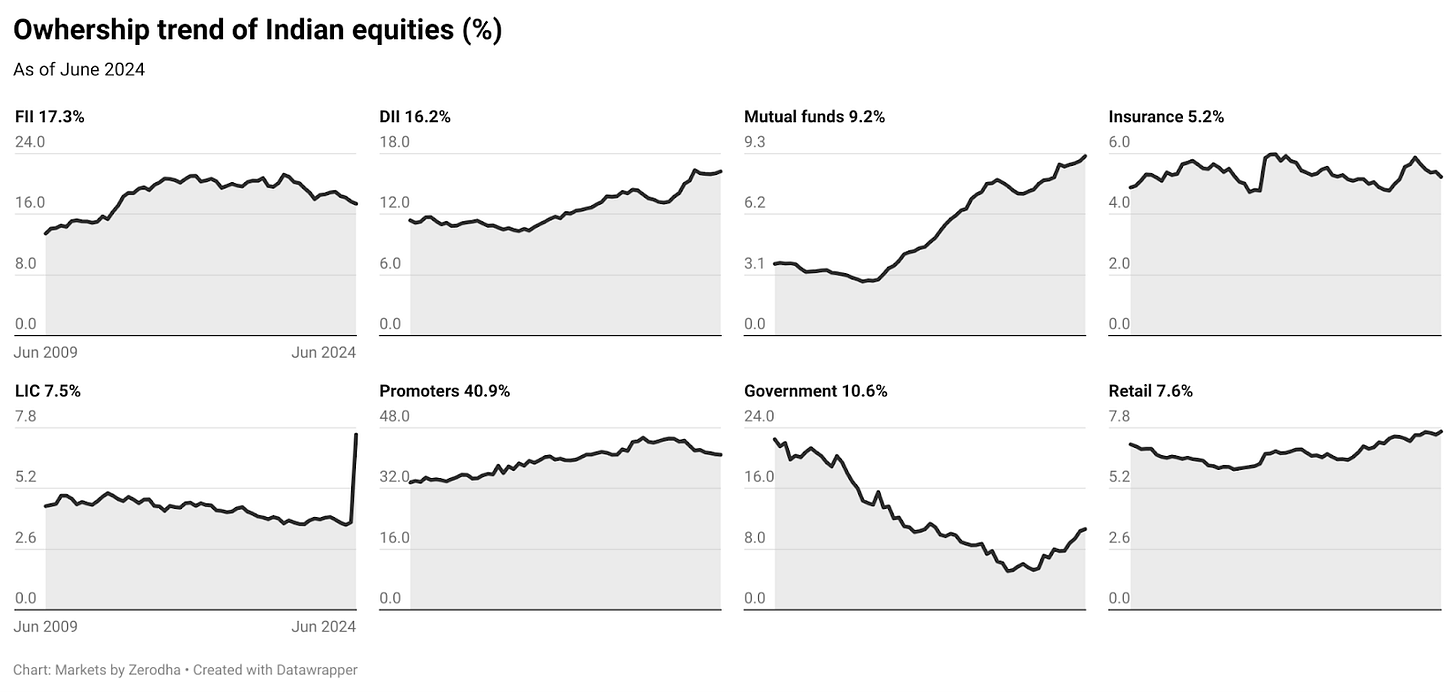

This shift highlights something important: the ownership of Indian companies is changing. Promoters are cutting back on their stakes, while retail investors and domestic institutions are filling the gap. For example, promoter shareholding has dropped to 32.4% from 36.3% in FY22. Meanwhile, domestic mutual funds have seen their stake rise from 7.7% to 9.2%.

So, should we be worried that promoters are selling while retail investors are stepping in? Does this suggest the market is peaking? It’s tough to say for sure. Some might see promoter selling as a warning sign, but it doesn’t automatically mean a downturn is coming. What’s clear is that market dynamics are shifting. The ownership landscape is evolving as retail investors and domestic institutions take a bigger role. Whether this marks a peak or just another phase of the market’s journey remains to be seen.

The steel industry is stuck between a rock and a hard place

India’s steel sector is at a critical crossroads right now. On one side, it’s one of the few major markets with real growth potential. But on the flip side, it’s facing some serious challenges that we can’t overlook.

First, let’s talk about the challenges. Between April and August this year, India turned into a net importer of steel, with imports jumping 25% and exports dropping 39% compared to the same time last year. A major reason behind this is the surge of cheap Chinese steel flooding the market, sold at prices even below production costs.

But despite these issues, there’s a promising long-term growth story here. The Indian government has set big goals, aiming to ramp up steel capacity from 180 million tonnes now to 300 million tonnes by 2030, driven by massive infrastructure development.

Looking at the numbers, McKinsey & Company predicts steel demand in India will grow from 139 million tonnes this year to between 195 and 215 million tonnes by 2030, an annual growth rate of about 6-7%. However, the government’s target is much higher at 300 million tonnes. Even the industry’s ambitious goal of 230-240 million tonnes falls short of this mark.

So why all the excitement about steel? India is in the middle of a huge infrastructure boom that directly boosts steel demand. Plus, rising incomes mean more steel consumption and more construction projects are shifting towards steel-intensive methods.

Currently, India uses about 100 kg of steel per person each year, far below the global average of 230 kg. The government wants to increase this to 160 kg per person by 2030. And there’s also room for growth in construction—India uses about 3 tonnes of cement for every tonne of steel, compared to the global average of 2.2 tonnes. Closing this gap could be another big boost for steel.

But it’s not all smooth sailing. The Indian steel sector faces two big hurdles: CBAM and China.

First, CBAM, or the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, is a carbon tax the European Union plans to impose on imports from countries with less strict climate rules. For Indian steelmakers, this means an extra $100 to $190 per tonne in taxes when selling to the EU, which could eat up as much as 28% of current prices, seriously hurting competitiveness.

CBAM could also impact the local market as stricter rules in Europe might push more high-carbon steel into Asian markets like India, creating tougher competition.

The second issue is China. China’s steel industry is struggling, and that’s affecting India. Chinese steel is flooding the market at ultra-low prices—even below production costs—just to keep mills running. About 80-90% of China’s steel industry is currently operating at a loss, which isn’t sustainable for them but is causing global disruptions in the short term. Some estimates suggest China could export up to 120 million tonnes of steel this year.

This situation has Indian steel producers worried, and they’re urging the government to step in, possibly by raising import duties to protect against these cheap imports. But it’s a delicate balance, as any protective measures need to align with international trade rules.

Climate change is another big factor. India’s steel industry isn’t ignoring it—they’re targeting net-zero emissions by 2047 and have set clear milestones to get there. They aim to cut emissions by 10-15% by 2030 and ramp up to 75-85% reductions between 2040 and 2050. However, this green transition won’t come cheap, with an estimated $1.2 to $1.3 trillion in total investment needed, including $420 to $470 billion in capital expenditures.

So how does India plan to reach that 300 million tonne capacity goal? Companies like ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel India (AMNS) are making significant investments. AMNS is pouring $5.1 billion into expanding its Hazira plant from 9 million tonnes to 15 million tonnes, with potential plans to scale up to 24 million tonnes later. They’re also working on two new plants in Odisha as part of a broader push to add 60-80 million tonnes of capacity over the next decade.

You might wonder, is there really a market for ‘green’ steel? The answer is yes, though it’s early days. Estimates suggest demand for low-emission or green steel could reach 4-5 million tonnes by 2030, driven by export sectors like automobiles, and growing domestic demand in areas like EVs, high-end appliances, and luxury real estate. Some companies are even seeing a ‘green premium’ of 20-30% over regular steel prices, proving there’s real value in going green.

So, what’s the takeaway?

India’s steel sector has enormous growth potential, thanks to the country’s infrastructure needs. But it’s also facing big challenges from global competition and environmental regulations. The industry is adapting by focusing on value-added products, cost-cutting, and new technologies. This is a long-term growth story, but it will need patience and careful navigation through tough times.

Tidbits:

OpenAI is restructuring into a for-profit benefit corporation, raising its valuation to $150 billion. CEO Sam Altman will receive a 7% equity stake as part of this shift, which aims to attract investors but raises concerns about AI safety governance. CTO Mira Murati will be leaving during these changes.

Swiggy’s unlisted stock price jumped 40% after SEBI approved its IPO, valuing the company at ₹1.16 lakh crore. The food delivery giant reported a 36% rise in operating revenue and plans to raise ₹10,375 crore through the IPO.

Mahindra & Mahindra is in talks to acquire a 50% stake in a joint venture with Skoda Auto Volkswagen India, a deal estimated at $800 million to $1 billion. This partnership aims to enhance tech and manufacturing capabilities, potentially increasing M&M’s annual production capacity.

TRAI has allowed Indian telecom operators to continue under current licenses until they expire, after which the new Telecommunications Act of 2023 will take effect.

India’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme has drawn over $17 billion in investments, leading to $131.6 billion in production across 14 sectors, creating nearly 1 million jobs and boosting domestic manufacturing.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

If you have any feedback, do let us know in the comments