How Zee lost trust in its founders

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Are Zee’s promoters facing a trust deficit?

Can ONDC really live up to its promise?

Are Zee’s promoters facing a trust deficit?

Last week, shareholders of Zee Entertainment Enterprises rejected a proposal to issue ₹2,237 crore worth of convertible warrants, which would have allowed the company's founding family to increase their ownership to 18.4%. The special resolution needed 75% approval to pass. It received only 59.5% votes in favor, with 40.5% voting against it.

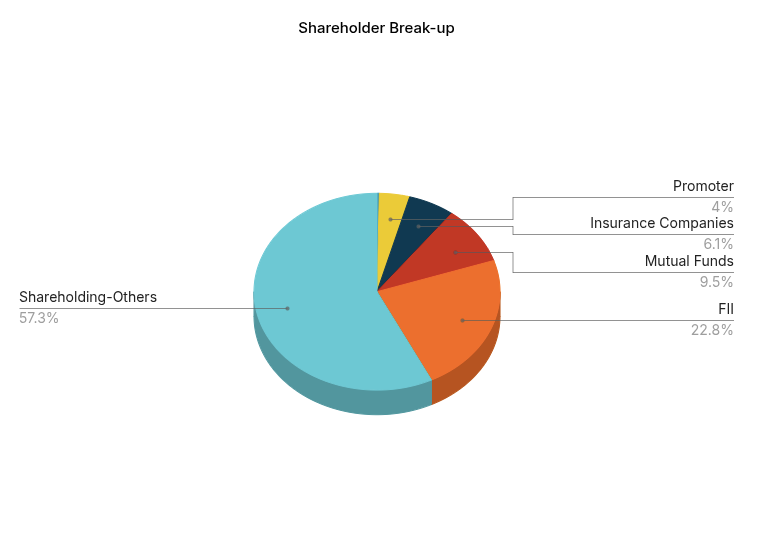

The rejection marked the latest chapter in a long series of events which saw its founding family — the Goenkas — go from creating the company to owning just 4% of it today.

How did the family end up in this position? Let’s break it down.

Who are the Zee promoters?

Back in 1973, Subhash Chandra (born Subhash Chandra Goenka) took over a loss-making, debt-ridden grain-trading business, called Messrs. Ramgopal Indraprasad, from his grandfather. He turned the company profitable in just a few years. By 1976, it was given a new, modern name: “Essel”.

Slowly, Subhash Chandra diversified away from grain trading to more complex businesses, like manufacturing. But his real ambitions lay in bolder projects — like theme parks, lotteries, or media properties.

In 1992, he launched Zee TV, India's first private satellite television channel. This was a revolutionary moment. It broke the government's monopoly on television, and changed Indian entertainment forever. Over time, this grew into an entire network of entertainment properties, with its many channels reaching over a billion viewers across the world.

But somewhere, he lost control over this giant.

Today, the Goenka family — which also includes Subash Chandra’s son, Punit Goenka — holds their stake in Zee through various companies under the “Essel Group” umbrella. Together, these entities own about 4% — or 3.99% to be precise — of Zee Entertainment.

From 43% to 4%

This 4% stake is a dramatic fall from their position just a few years ago. As recently as 2016, they owned 43% of Zee Entertainment. What happened in between?

That, it turns out, is a long story.

The family started reducing its stake in the company all the way back in 2001. They sold 5 million shares of Zee Telefilms (as the company was then called) to a US based institutional investor. The sale itself wasn’t shocking — except that it was meant to cover ₹2.20 billion in debts they owed to Zee Telefilms itself.

This would soon become a recurring pattern. The family was constantly indebted, and would keep selling shares to get by. Just two years later, for instance, in 2003, they sold another 12.38 million shares — 3% of the company's equity — to foreign investors to clear more dues.

But the real crisis came in 2019. By then, the Essel Group's total debt reached ₹17,000 crore across 88 companies. Worse still, this debt came in an environment that made it impossible to pay off.

This was in the days after the IL&FS (Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services) default in 2018. With such a financial behemoth falling apart, there was a major freeze in credit markets. To this point, the Essel Group had been managing its debt by rolling over existing loans through new financing. However, with the IL&FS collapse, this was no longer an option. Banks and financial institutions were completely spooked, making them extremely cautious about lending.

Suddenly, the Essel Group’s manageable debt burden turned into an acute liquidity crisis. And making things worse was some terrible timing.

Subhash Chandra had pledged a significant portion of his Zee Entertainment shares as collateral for these loans. That’s a common practice, but it comes at a risk: if the price of your shares falls, the collateral suddenly loses value.

That’s precisely what happened. In January 2019, a news report alleged that the Zee group had moved money around for companies that were trying to get around demonetisation. With this, the stock prices of Zee Entertainment plummeted — falling nearly 33% in one day. That wasn’t just bad for investors; their loan collateral, too, suddenly lost one-third of its value. Lenders issued margin calls, demanding additional collateral or repayment.

The family was in a bind. Unable to meet these demands, they were forced to sell large blocks of pledged Zee Entertainment Entertainment shares to raise cash and avoid default. The more they sold, the lower their ownership fell. Between 2018 and 2020, their stake dropped from 43% to just 4%, as they sold shares to pay off group debts.

Beyond Financial Problems

This is the situation the Goenka family was trying to dig themselves out of with the warrant issue. And perhaps they would have. Only, over the years, they also bled away their credibility with Zee’s shareholders.

The first battles

In September 2021, Invesco Developing Markets Fund and OFI Global China Fund LLC, which together held ~18% of Zee Entertainment's shares, took an unprecedented step: they called for an Extraordinary General Meeting to remove Punit Goenka as its Managing Director and CEO. They also sought the removal of two other directors, planning to appoint six new independent directors in their place.

They claimed that Zee Entertainment’s board had given its blessing for something egregious — merging its media properties with those of Sony Pictures Networks India — without telling its shareholders. If this is how such serious decisions were handled, there were clearly serious governance issues in the company.

Zee Entertainment initially rejected the EGM, claiming that the investors lacked the approval required from SEBI and the federal broadcasting ministry to initiate such a move. But while Punit Goenka stayed on, the other two directors Invesco named soon resigned.

An intense legal battle followed. The company's future leadership was clouded in profound uncertainty.

The Sony saga

Things eventually cooled down.

Slowly, people came around to the idea that the Sony merger was a potential solution to the company's problems. The merger was worth $10 billion, and would have created India’s second largest entertainment network. Under the proposed deal, Zee Entertainment’s shareholders would own 47.07% of this new media giant.

Invesco, too, came to see the merits of the merger. After all, it would achieve their goal of bringing in a more professional management, while reducing the Goenka family's control. In March 2022, they dropped their legal challenge and decided not to pursue the EGM, backing the Sony deal instead.

But in a couple of years, it all fell apart.

In 2024, Sony cancelled the deal, claiming that Zee Entertainment failed to meet the merger’s agreement conditions. It demanded a $90 million penalty from Zee Entertainment for allegedly breaking the merger terms, even as Zee Entertainment “categorically” denied breaching the pact.

We aren’t sure of why things soured. But according to a 62-page termination notice reviewed by Reuters, Sony claimed that some of the “financial conditions” of the deal had not been satisfied, and that Zee Entertainment had done nothing to remedy them. One of them, it seems, is that Zee Entertainment simply didn’t have the amount of cash it was supposed to under the deal. Sony reserved sharp words for Zee Entertainment, saying these breaches were "not remediable and any further attempts to mutually discuss would be an empty formality…”.

Beyond that, though, the report also cited "ongoing investigation" as one of their concerns.

SEBI’s investigations

The “ongoing investigations” that worried Sony were most likely investigations by SEBI, into possible “fund diversion” — essentially, that the Goenka family had moved money out of Zee Entertainment to other Essel Group companies.

Zee’s promoters had taken loans for some Essel Group companies from Yes Bank. For this, they gave the bank a “letter of comfort” — supposedly telling it that if they failed to repay the loan, that money could be deducted from Zee Entertainment’s own deposits. Only, they did so without the consent of the company’s board or shareholders. Zee Entertainment was unknowingly made responsible for loans that benefited its promoters, but not itself.

Those companies soon defaulted. Yes Bank took ₹200 crore from Zee Entertainment's fixed deposits.

Later on, those companies supposedly “paid back” this amount to Zee Entertainment. But as SEBI dug deeper, it found that this “repayment” was all just financial jugglery. The money originated from Zee Entertainment or other listed Essel companies, passed through 13+ shell companies, and went back to Zee Entertainment. It looked like they had paid the company back, but it was all an illusion.

As SEBI dug deeper, things seemed uglier. It looked like ~₹2,000 crore may have been diverted from Zee Entertainment to other group companies.

In August 2023, SEBI banned both Subhash Chandra and Punit Goenka from holding key positions in any listed company. While that was later set aside, the regulatory pressure continued. In January 2025, in fact, SEBI refused to settle the matter.

This is just one part of a broader scrutiny around the Essel Group. The Enforcement Directorate has also conducted searches of Essel Group companies in connection with money laundering investigations.

Punit Goenka is removed

As things got worse, Zee Entertainment’s shareholders turned on its promoters.

While Punit Goenka had survived the previous termination attempt, his five-year term was coming to a close in 2024. And his re-appointment seemed far from guaranteed.

On October 18, 2024, the company’s board approved his reappointment as Managing Director for another five-year term. But the company’s shareholders would have to confirm it at the upcoming Annual General Meeting on November 28.

This looked increasingly difficult. Already, two proxy advisory firms had issued reports recommending that shareholders vote against Goenka's reappointment, stating concerns about his leadership and the company's performance under his tenure.

Goenka tried getting around this. On November 18, he voluntarily resigned as Managing Director with immediate effect, supposedly to “entirely focus on my operational responsibilities." The board accepted this resignation, but kept him as CEO — something that doesn’t require shareholder approval. Five days later, Goenka officially withdrew his consent for reappointment as Managing Director.

Instead of becoming Managing Director, now, he was seeking shareholder approval to stay on as ordinary director on the company's board. The shareholders, however, delivered a strong message of no confidence. At the company’s Annual General Meeting, they rejected his reappointment as a director. The voting was close — only 49.54% voted in favor while 50.46% voted against the resolution. But he lost.

For the first time since Zee was founded, no member of the Chandra-Goenka family occupied a board position on any of the four listed Zee companies.

Bottom line

The July 2025 warrant rejection was only the tip of the iceberg.

Zee Entertainment was once a symbol of what private enterprise could achieve in post-liberalisation India. In its day, the company had reshaped Indian media. But over time, that legacy has been clouded by financial missteps, governance failures, and a deep erosion of trust.

Its promoters have seen a long, painful fall from grace. What began as chronic over-leverage has culminated in a complete loss of shareholder confidence. Zee’s once-passive shareholders are now watching them closely. Their wings have been clipped. Their most recent attempt to claw back was firmly rejected.

Can they build back confidence from here? Only time will tell.

Can ONDC really live up to its promise?

It’s been a stormy time for Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC), India’s public infrastructure for e-commerce.

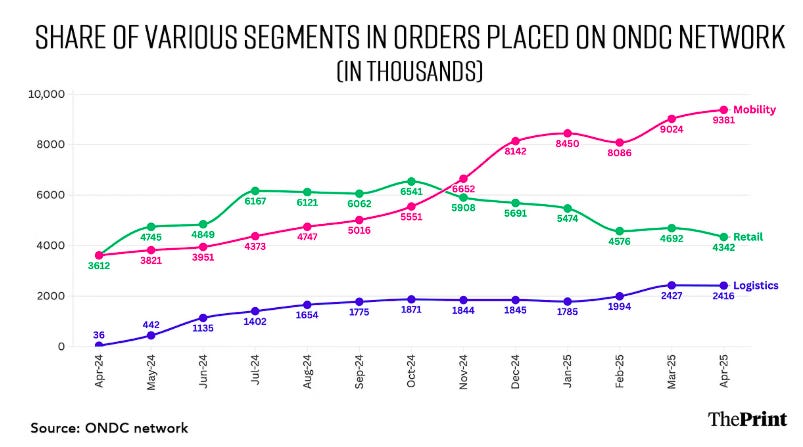

Last year was a struggle for the network. Between October 2024 and February 2025, the number of monthly retail orders through the network fell by 31% to 46 lakh. It was spending a lot on fueling growth, but the results weren’t showing. So, it reduced the monthly incentives for the players in its network by ten times earlier this year — from ₹3 crore to ₹30 lakh. But naturally, that slowed its growth even further.

The tumult spurred a long line of exits. Their CEO, chief business officer, and non-executive chairperson, have all resigned this year.

ONDC hasn’t lost hope yet. If anything, it’s doubling down. Last week, they revealed a new subsidy plan worth ₹150 crore in the works. But can they live up to its promise? That is, really, a question about whether you can bring a whole new philosophy to the business of e-commerce.

The philosophy behind ONDC

Think of the last time you ordered something on Amazon.

You searched for an item. You liked something sold by a specific seller. You bought it, going through Amazon’s payment gateway. The order was listed on Amazon’s systems. The product went from one of its warehouses to the supply center nearest to where you live. And an Amazon delivery driver delivered it to you.

Amazon owns this entire process.

Sellers pay Amazon for listing their goods. The more they pay, the more they show up on your search — even if they aren’t the most relevant to you. Buying an Amazon listing is really like paying rent for prime property (something that’s made small Indian sellers very unhappy).

Meanwhile, Amazon controls how you discover products. It has mountains of data on you; it knows what you buy, and how. But more importantly, it has your attention. And for digital markets, attention is arguably the most precious commodity there is. Amazon sells this attention to merchants. If you’ve ever felt like you’re spending a lot of time scrolling through things you don’t need, that might be because someone bought your time.

Amazon also dominates a lot else — from warehouses to last-mile delivery. Every such step gives it an added layer of power and control. And there are many ways it can use that power — a lot of which you might not like.

This isn’t just Amazon, by the way. From Uber to Swiggy, the internet is full of businesses that connect buyers and sellers of something, but gain tremendous power by connecting the two. They’re technically just “middlemen,” but they’re also the most powerful entities in their respective ecosystems.

Enter ONDC

ONDC wants to be the antidote to this power.

Its goal is to unbundle the networks behind online markets into smaller building blocks — so that anyone can choose how they want to participate. You don’t have to be the next Amazon or Uber, doing everything from end to end. Maybe you just list sellers. Maybe you only build a user-friendly app for buyers. Maybe you don’t write any code at all, and just handle deliveries in the real world.

Ordinarily, that kind of focus just isn’t possible. If you want to enter such online businesses, you need to do everything yourself — or find someone who does. Otherwise, who ties it all together?

ONDC has an answer: anyone. Every link in this chain could be a new business opportunity.

ONDC hopes to be the connective tissue between completely different entities that specialise in just doing one task well. It’s creating digital “infrastructure” to connect these entities. This would allow such markets to be “decentralised”, ensuring that nobody gets the kind of power that comes with controlling an entire ecosystem.

We spoke about “interoperability” when we were looking at UPI yesterday. This is similar, but instead of payments, it could work with anything. Groceries, food delivery, ride-hailing autos — ONDC could plug in anywhere.

But what is ONDC?

Here’s what ONDC is not — it isn’t a consumer app. It has no user interface of its own. ONDC is best understood as a way for different participants in an e-commerce network to talk to each other.

At its heart is an open protocol called Beckn. The Beckn protocol smoothens communication between broadly 5 kinds of roles:

Buyer apps: A buyer app might be something like what you see, as a buyer, on Zomato or Amazon, where users browse for what they would like.

Seller apps: A seller app provides the product catalogs (and even inventory) from sellers — for instance, a company like boAt.

Gateway: Gateways come in between the two, matching buyers to relevant sellers. For example, a gateway gets a signal from a buyer app that a buyer in Bangalore wants a TV within ₹50,000, and finds a relevant seller app that could provide one.

Technology service provider (TSP): You could sit outside this chain, but give technological services to others on the network — say, certain automating things like bill generation for sellers.

Logistics providers: You could also do the real-world work of taking goods from place-to-place, like courier services, or mobility players to send you food (like Namma Yatri)

If you’re using ONDC, you interact with these entities, not ONDC itself. In essence, ONDC allows you to separate the various cogs of e-commerce — search, discovery, fulfilment, and so on — from each other.

At least in theory, this has inherent benefits over an Amazon-style “closed loop” model. For one, it creates more competition at every step of a transaction. That could reflect, for instance, in lower commissions — where Zomato charges 18-25%, for instance, players competing on ONDC could give something closer to 10%. It might also ensure that the results you get are more relevant. And so on.

We highly recommend going through two pieces if you’re more curious about the nitty-gritties of ONDC: Tigerfeathers’ ONDC deep dive, and this piece by Sangeet Paul Choudary.

But has it actually worked according to plan?

The performance so far

In ONDC’s second year — 2023 — it seemed like it would take e-commerce by storm.

That single year, it went from 50 transactions a day in January, to 1,00,000 daily transactions by August. Its seller base rose similarly — from 800 to 1,40,000 sellers in the same time span.

Mobility emerged as the largest use-case of ONDC — led by the success of the ride-hailing app, Namma Yatri (although the relationship between ONDC and Namma Yatri is more nuanced). If you haven’t tried it before, it’s a little like Uber, except that it doesn’t take a commission for every ride. In 3 years, it has crossed 100 million rides, unlocking earnings of ₹1,600 crore for 6 lakh drivers. But more than its own success, the real revolution was in how it transformed the entire ride-hailing market. Now, all major ride-hailing players — including Uber — have been forced to adopt the zero-commission model.

Then comes retail. Food delivery is, by far, ONDC’s biggest retail success story. From 4,000 monthly orders in March 2023, ONDC reached 5 lakh monthly orders a year later — drawing both local restaurants and international players (like KFC).

It’s not hard to see why it’s doing well. Restaurants are pissed with the hefty commissions charged by Zomato and Swiggy, which ONDC waves off. It also became a gateway for ride-hailing apps to enter the food delivery business, bringing some momentum.

However, this growth comes with an asterisk mark — so far, it was fueled by subsidies, which translated to cheap prices. When these subsidies were cut, that price advantage evaporated, and retail growth slowed down fast. Platforms like PhonePe’s Pincode even exited ONDC after the cuts.

In fact, as subsidies were slashed, you could see a distinct shift in the mix of segments that drive ONDC’s growth — with mobility and logistics inching up at retail’s expense.

Is unbundling the real answer?

So why is ONDC stumbling in retail?

There are many issues that an ambitious idea like ONDC has to grapple with. They all stem right out of its core promise: unbundling e-commerce.

Let’s unbundle this. ONDC splits the functions of search, discovery, fulfilment, and others into different components. But in doing so, it adds a small coordination cost between each function. The more steps / stakeholders in the supply chain, the higher these costs become.

This could, for instance, create a liability problem. Consider this: imagine you buy something from a buyer-side platform, but they have no links to the seller, or to the delivery personnel on the ground. What happens if something goes wrong? Who do you complain to? Who gives you a refund? So far, ONDC has depended on third parties to resolve online disputes. But this is hardly satisfactory. In a survey by LocalCircles, 35% of respondents were unhappy with the support.

In contrast, if Zomato screws up, you just call Zomato. It’s their headache to figure out where the problem lies.

The ONDC essentially tries to solve for every use case at once. But these use cases are different — retail works differently from mobility, for instance — and the more you try to generalise, the harder it is to remove these costs. If you want to run a local delivery service, for instance, you need everyone to be integrated deeply: with real-time inventory sync, delivery tracking, returns processing, etc. But the ONDC isn’t specific enough for all of this to be built in. In trying to solve everything, it optimises for nothing.

This could perhaps be fixed if you could somehow command higher premiums, giving you money to plug those gaps with. But if anything, ONDC actually pushes for thinner margins. There’s no financial room to absorb the inefficiencies of decentralisation.

Look at existing companies in the space. Amazon, Flipkart, Zomato, Swiggy — they don’t control the entire stack only for power, but also to synchronise functions and optimise at scale. Because existing platforms bundle all their functions together, they’re better coordinated and can drive down costs, especially as they scale. Their centralisation permits a tight operational choreography; it lets them route data efficiently, pre-empt failures, and subsidise weak links using stronger ones. ONDC breaks this integration. Openness, here, can come at the cost of operational reliability.

Traditional platforms can also invest in intuitive interfaces, with smooth flows across its functions — making them much easier to navigate as a user. On the other hand, apps linked to ONDC tend to be clunky, and are limited in what they can do. In a survey, more than 50% found these interfaces tough to navigate. Fundamentally, if you’re a user, ONDC hasn’t done much else to make itself attractive, besides offering cheap prices floated by subsidies. And with the subsidies gone, the attraction loses more charm.

Still early days

ONDC does understand these problems.

For now, it’s responding with more subsidies. But capital or subsidies aren’t the only strategy it can, or should, deploy. Those are only useful until ONDC reaches a critical mass that can sustain itself. And meanwhile, they’re competing against big players with lots of capital.

The answer, ultimately, lies in ONDC incentivising better features and use cases than traditional platforms. That is ONDC’s next goal. They want to help sellers optimize their prices, and make the user experience more personalized. They’re actively inviting private players to help them out.

There’s also the chance that the ONDC doesn’t disrupt today’s platforms, but still sees success — by doubling down on new categories, where it has already seen bright spots. For instance, ONDC has been remarkably successful in getting India’s smaller sellers and kirana stores aboard the digital realm. Maybe ONDC creates new types of businesses around such categories.

In 3 years, ONDC has made enough of an impact to stay for good. But how it changes e-commerce in India is a question it has yet to figure out.

TIDBITS

We looked at how India’s CNG sector is facing a squeeze — demand’s still growing, but supply? Not so much. Now there’s some relief on the horizon.

GAIL has signed a long-term LNG supply deal with Vitol Asia — locking in 1 MTPA of LNG for 10 years, starting 2026. The deal is part of GAIL’s push to strengthen its long-term portfolio and insulate customers from short-term shocks in domestic gas production.

Source: Business LineWe explored Reliance’s entrance in India’s $18 billion soft drink war with Campa Cola. Now, that push has crossed borders.

Campa Cola has launched in Nepal. Through a partnership with Chaudhary Group — the country’s largest conglomerate — Reliance has officially taken its heritage brand global. This comes after its earlier foray into GCC markets. The move aligns with RCPL’s strategy to price aggressively and scale quickly. In Nepal, 250 ml Campa bottles are priced at NRs. 30, significantly undercutting global rivals.

Source: Business LineWe wrote not one, but two stories on the fascinating port industry. And there’s news on that front.

Vizhinjam International Seaport in Kerala, after a successful first year of operations, is set to embark on its second phase of expansion starting September 1, 2025. The ₹10,000 crore project aims to enhance capacity and connectivity, positioning the port as a key player in India's maritime infrastructure.

Source: The HinduInflation is a hot topic in our country and around the world. Luckily, India’s actual inflation rate appears to be cooling down majorly.

India's retail inflation has dropped to a six-year low of 2.10% in June 2025, driven by easing food prices. This decline raises expectations for another interest rate cut by the Reserve Bank of India to stimulate economic growth.

Source: PIBSolar power recently made electricity free for a brief moment because of its sheer abundance. And the sheer abundance has gotten us to this happy update.

India has achieved a significant milestone by reaching 50% of its installed electricity capacity from non-fossil fuel sources, five years ahead of its 2030 target under the Paris Agreement.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Prerana and Manie.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉