How the Indian Railways became electrified

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The electrification of Indian Railways

Reliance adds more tricks to its juggling act

The electrification of Indian Railways

In FY24, the mighty Indian Railways carried a whopping 6.9 billion passengers, while loading 1.58 billion tonnes of freight, on a network that’s 69,000 km long. This is an unimaginable, dazzling scale that we can’t possibly ignore. If the Indian Railways were down for even a day, the Indian economy as we know it today would come to a screeching halt.

So, we decided to look at various aspects of the various moving parts behind our rail infrastructure. Today’s episode is about the energy stack that keeps Indian rail running. After all, the Indian Railways is one of India’s largest energy consumers.

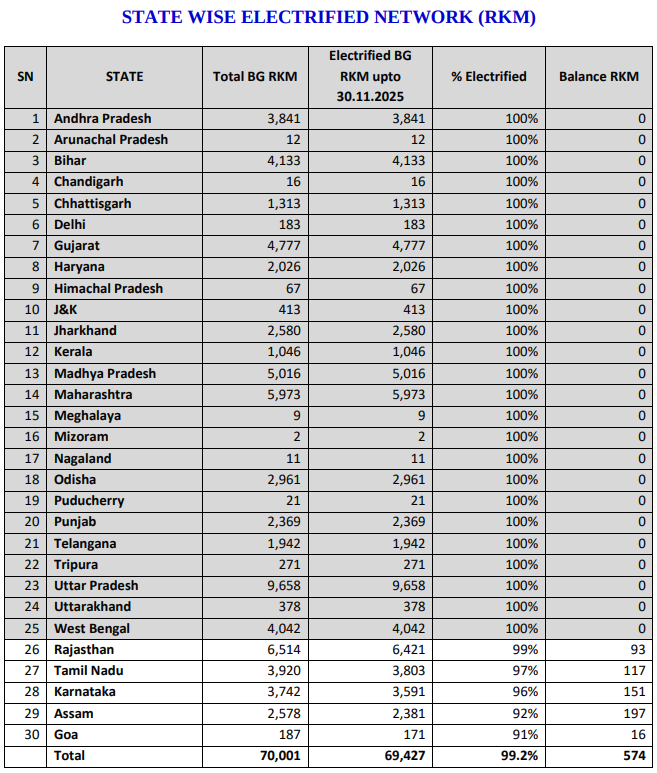

By late 2025, ~99% of the rail network became electrified, finalizing the railways’ transformation from being a diesel consumer to an electricity buyer. This has also changed the way the railways operate — how it builds new lines, how it connects to the larger Indian electricity grid, its new cost structure, and the new risks it’s exposed to.

Let’s dive into how electrification makes a material difference to the Indian railways.

A brief history

The first question worth asking is: why electrification?

At first glance, electrification seems like going in circles. The older steam locomotives used to be powered by coal, but then they were replaced by diesel. Now, diesel-powered engines are being replaced by electricity generated largely from coal-fired power plants. If the grid burns coal anyway, what is gained?

The answer lies in thermodynamic efficiency. Large centralised power plants operate at higher thermal efficiencies than locomotive diesel engines. Electric motors are able to effectively make use of over 90% of electrical energy into running a train, compared to 35-40% for diesel engines.

Electric traction also enables something called regenerative braking. Here, when an electric train slows down, its motors act as generators, feeding electricity back into the grid. Diesel locomotives, however, release this braking energy as heat that can’t be used again.

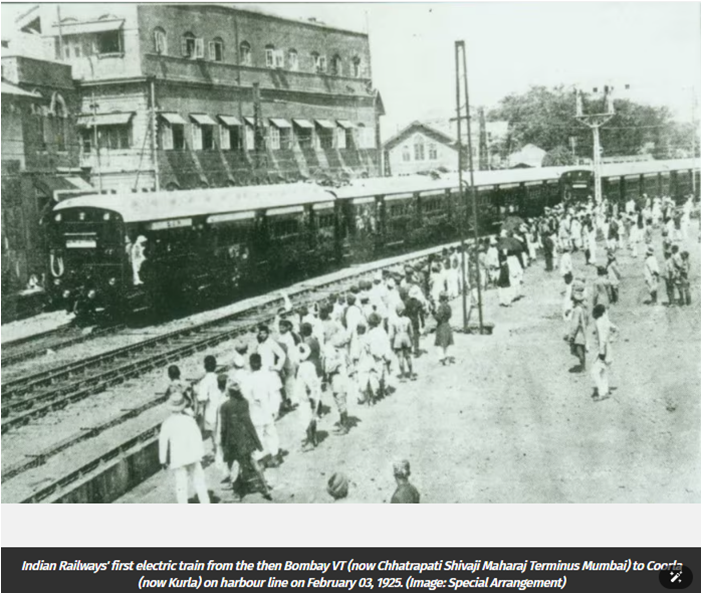

It is with this motivation that India pursued a path to electrification as early as the early 20th century, but progress was slow. Mumbai’s suburban lines, for instance, were electrified in the 1920s. But these early systems used direct current (DC) at low voltages, which suffered significant voltage drops over distance. At the time, India's electricity grid was not developed well enough to support long-distance electrification.

After independence, diesel became the dominant energy form of our trains, replacing steam. It was a faster and cheaper alternative, since it didn’t require the massive upfront capital for electrification.

However, as independent India developed its grid, it took electrification more seriously. In 1961, Indian Railways adopted a 25-kilovolt alternating current (25 kV AC) system as the standard for mainline electrification. Unlike the DC system in Mumbai, the new standard allowed power to be transmitted over much longer distances. The first mainline sections were electrified in the early 1960s in the East. By 1968, older DC lines had been converted to 25 kV AC.

This standardisation meant that any electric locomotive built in India could operate anywhere on the electrified network. It also meant commitment — once a route was electrified, the infrastructure and equipment would remain in place for decades. But getting to this point took decades.

The infrastructure behind electrification

Now, how does the infrastructure behind electrification work?

Railway electrification is a massive process. It requires building a separate power supply network — including traction substations, high-voltage transmission lines, and control systems — that connects the rail to the electricity grid effectively. This involves coordination with state electricity boards and discoms, which control India’s grid. This entire process is overseen from the top by the Central Organisation for Railway Electrification (CORE).

The physical system has two primary components. The first is overhead wires suspended above the track, which carry the electrical current. Electric locomotives have a pantograph — essentially a hinged arm with a contact pad that stays pressed against the wire as the train moves, like a moving electrical plug.

The second component is the traction substation, which supplies electricity to the wires. It takes high-voltage electricity from the main grid and converts it to the 25 kV voltage that trains need. Think of it as a transformer. If something goes wrong, like a short circuit, the substation automatically cuts power to the wire segment to prevent damage.

In the olden days when DC was used, a “substation” meant something different. They merely took power from a plant and connected it to rail. But, direct current loses its voltage quickly, making a given current weaker as it travels longer.

So, back then, many substations had to be installed in quick proximity to each other. Today, modern AC substations help transmit power over much longer distances. This reduces the number of substations needed — on average, substations exist every 50-80 km now.

Yet, despite this improvement, it’s still really hard to build electrification infrastructure. Installing overhead wires while trains continue to run smoothly requires careful scheduling of work blocks. On busy routes, only a few hours of working time are available each day.

Moreover, retrofitting older routes built in the steam and diesel eras often required costly modifications. For instance, bridges and tunnels built a century ago lacked the vertical clearance needed for 25 kV wires. This meant raising bridges, lowering track beds, or rebuilding station foot overbridges, each requiring separate engineering projects and traffic disruptions.

This becomes a Herculean task in the densest of terrains. Electrifying routes through the Western Ghats and the Himalayan areas requires installing substations in areas with steep gradients, poor road access, and landslide-prone slopes. These areas can’t be skipped, either.

Consider the Sakleshpur-Subrahmanya section in Karnataka. Across 55 km, the railway had to wire 57 tunnels and 226 bridges through landslide-prone terrain. No roads existed, so every piece of equipment came by rail. It took 2 whole years to complete.

Coordination with state power utilities has been another persistent challenge. Take the Bengaluru-Hubballi line in Karnataka, for instance. The route completed electrification in June 2023, but trains continued running partly on diesel until mid-2025. This was because out of 25 planned traction substations, only 12 were functional — the rest were stalled by land acquisition disputes and delays in laying transmission lines. As a result, 8 trains on the route were still burning ~764,000 litres of diesel monthly, costing ~₹4.36 crore.

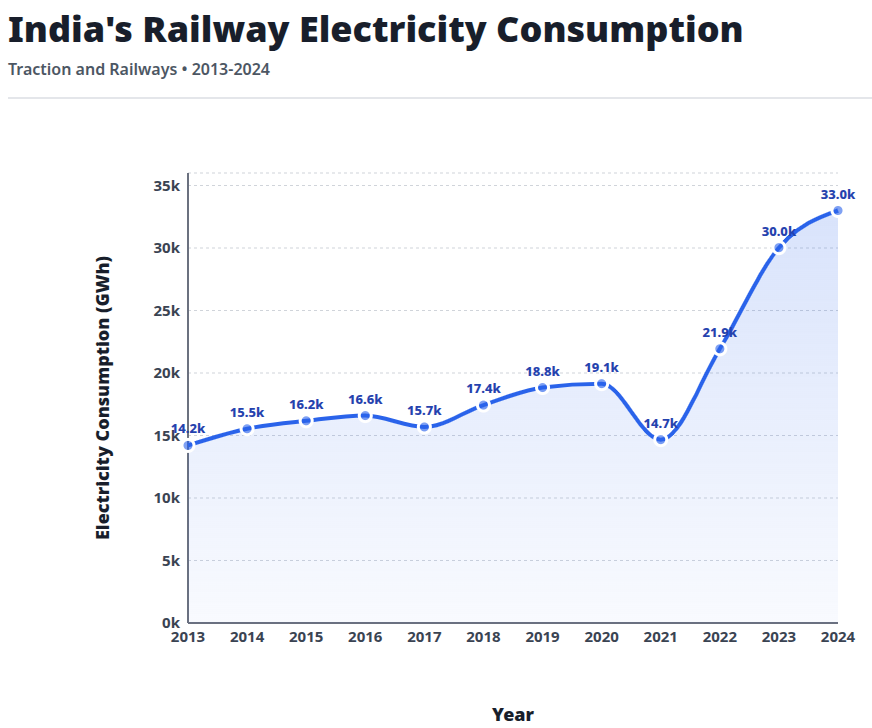

Despite these challenges, Indian Railways has accelerated electrification dramatically over the past decade. Between 2014-2023, the railway electrified over 30,000 km — more than in the previous six decades combined. As of early 2025, only a few stretches remained. Some diesel locomotives are still kept for emergencies, but the vast majority of routes are wired.

What electrification changes operationally

How has electrification changed how Indian rail operates day-to-day? The biggest fundamental change is that its risk profile has basically shifted from fuel logistics to power infrastructure management.

To start with, what needs to be maintained is different now. Electric locomotives have no combustion engines to burn diesel — which means no pistons, turbochargers, or radiators. Maintenance is focused almost wholly on transformers, traction motors, and electronics. The workload per locomotive is lower than for diesel.

But the railway must now maintain a lot more fixed electrical infrastructure. It has to ensure that its power lines have low transmission losses. It will also have to ensure adequate supply of power to certain areas. By connecting to the grid, the Indian Railways becomes dependent on how power prices work in India. In many ways, it bears similar risks as state utilities do.

This changes the railway’s cost structure. Diesel expenses scale with traffic and remain exposed to oil price volatility. Electric traction, though, is far more economical than diesel. In FY24 alone, the railways saved over ₹4,700 crore by reducing diesel consumption. However, while variable costs fall, fixed costs for the railways rise. Now, they have to spend on building and maintaining infrastructure for electrification. The upfront capital requirement is high, but ongoing operating costs get stabler over time.

Electric locomotives offer one more advantage. When a train is too heavy for one locomotive engine, the railway can use two or three together without the overheating problems that limit diesel engines. This allows longer, heavier freight trains for bulk commodities like coal, iron ore, and grain.

The trade-off is that fuel price volatility is replaced by dependence on grid reliability and state power utilities. A grid failure can leave trains stranded. The railway still keeps diesel locomotives and other contingencies on standby to hedge against such risks.

Beyond coal

The next stage of the Indian Railways’ power ambitions is renewables. These efforts are still in their infancy, and aren’t yet large enough to power the network independently. But, they’re moving fast, proving to be an effective supplement to the grid.

As of November 2025, Indian Railways has commissioned 898 MW of solar power capacity, a nearly 244-fold increase from just 3.68 MW in 2014. This solar capacity is now installed at 2,626 railway stations across the country. Most of it is used for traction purposes, directly contributing to the requirements of electric train operations. The remaining meets non-traction needs like station lighting and railway quarters.

It is also testing battery-powered and hydrogen-fueled trains for short stretches like rail yards, and in lines where overhead wires aren’t easy to build. In September 2025, Concord Control Systems successfully retrofitted a diesel locomotive to run on lithium-ferro-phosphate (LFP) batteries, and hydrogen train trials began in 2025. These, however, are hardly mature compared to other energy sources.

The railways’ approach to renewables has so far been to plug the gaps the grid can’t fill. Solar may help them reduce dependence on the grid during peak hours. Batteries handle short distances, especially where electrification is rather difficult.

Conclusion

The electrification of Indian Railways is not a single project with a clear finish line. It has been a long reorganisation of how the railways consumes energy and manages risk. In essence, it is a complete paradigm change.

And the reorganisation hasn’t been easy, either. Grid reliability and redundancy are uneven across the country. The railway’s ability to secure reliable, affordable electricity depends on coordination with many agencies. Maintaining thousands of kilometres of overhead wires and ensuring substation uptime every single day is no easy task.

The positive sign is that electrification is already yielding the efficiency gains that were envisioned. The harder question is whether the railway and state utilities can maintain the coordination this new system now requires.

Reliance adds more tricks to its juggling act

Earnings season is back.

Every time we try to cover Reliance, we realize how difficult it is to write about all that went down in a single quarter — all because of the sheer enormity of the company. Today, Reliance sells petrol, internet, gold, and broccoli, produces saas bahu shows, and is busy building factories that will eventually churn out solar panels and batteries. Very few companies straddle so many parts of the economy at once, but that’s exactly why we have to pay attention to it.

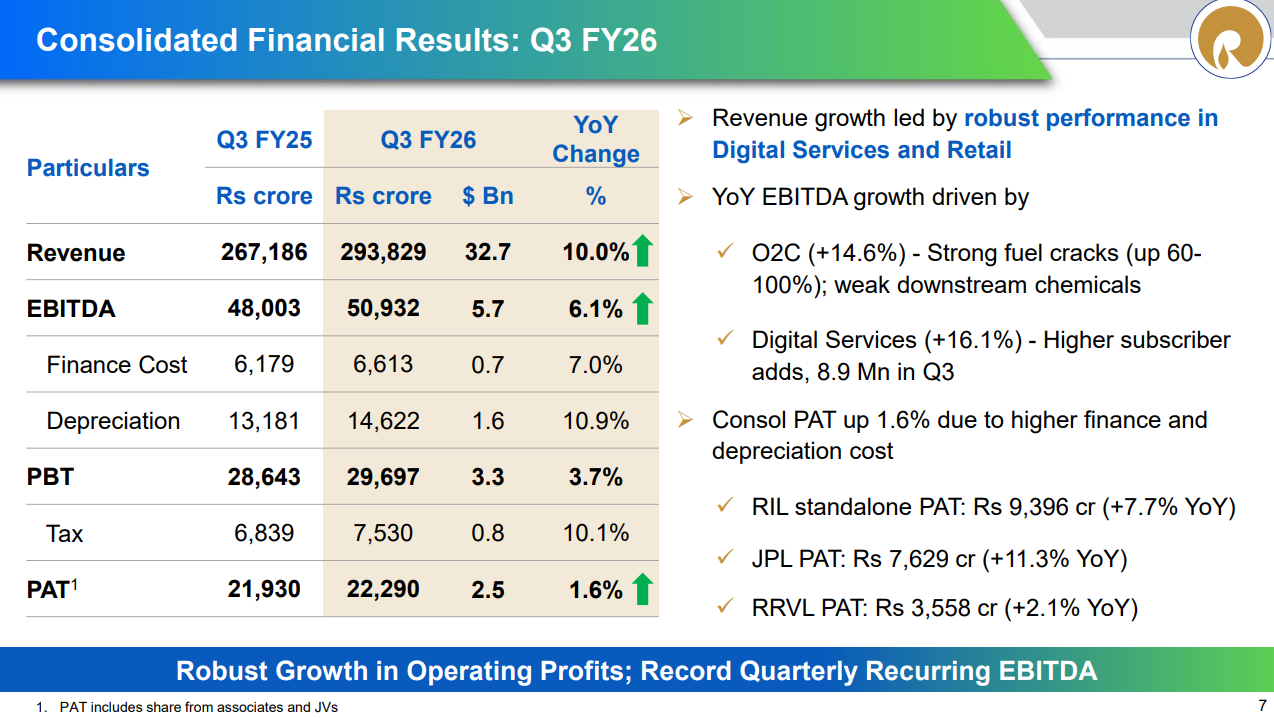

This quarter makes our job no easier — maybe harder. At a headline level, things look fine: revenue and profits are up, and the company is still spending a lot of money. But once you start pulling the numbers apart, you realise different parts of the business are doing very different things. Some are now clearly pulling their weight, while others are still swinging wildly with cycles or burning cash.

Jio Dhan Dhana Dhan?

To make sense of it all, we start with Jio.

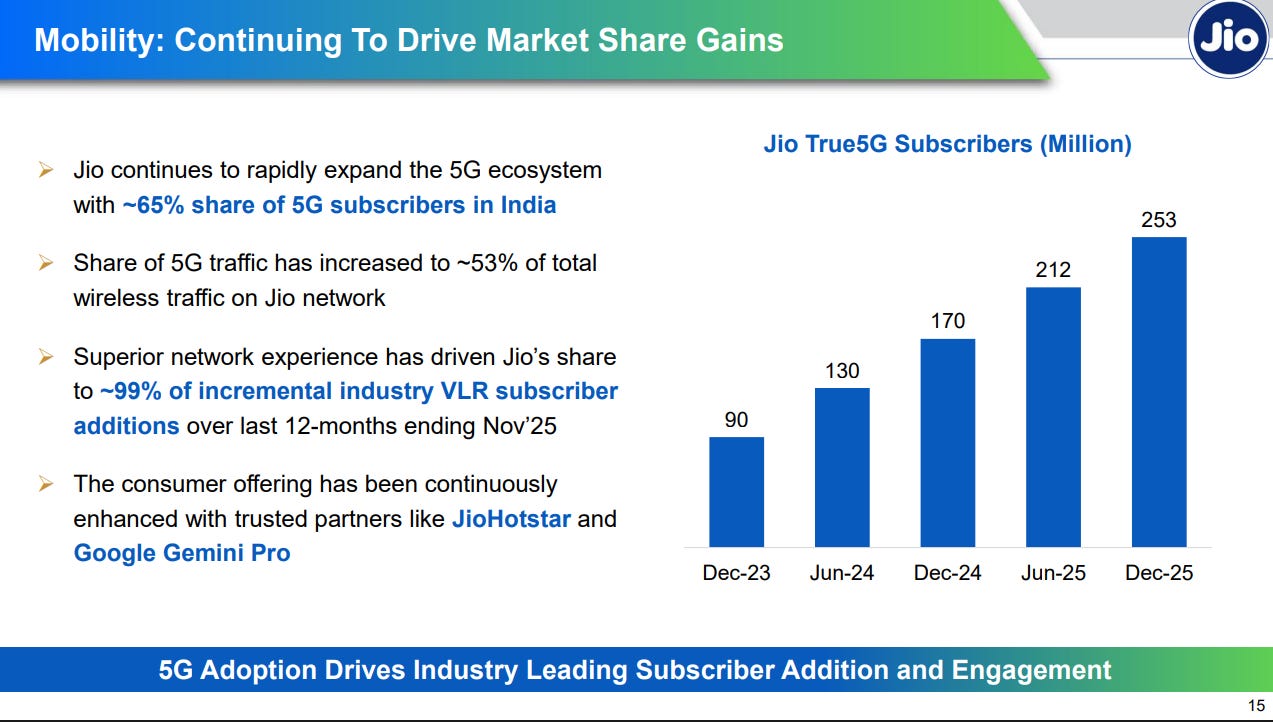

During the quarter, Jio added close to 9 million subscribers, taking its total user base to a little over 515 million. On its own, that figure isn’t particularly jaw-dropping. India’s mobile market is already saturated — almost everyone who wants a phone connection already has one. So adding users today is not about tapping some vast new pool of first-time customers. What matters more is who those new users are and why they choose one operator over another.

Interestingly, as per management, Jio accounted for almost all of the net new active mobile users added over the past year. They claimed that 99 out of every 100 users who signed up chose Jio.

That does not mean Jio has swallowed the entire market, or that competitors no longer matter. It does mean that in a market where overall growth has slowed sharply, whatever growth still exists is becoming increasingly concentrated.

Jio’s average revenue per user (ARPU) also moved up during the quarter, almost touching ₹214 from ~₹203 last year. Usually, ARPU growth comes from tariff hikes, but that’s not the case this time. A growing share of Jio’s users is moving to 5G plans, which are typically priced higher than older 4G options. Data consumption per user continues to rise, and as people use more data, they tend to drift towards higher-value plans.

Jio is also adding more fixed wireless broadband customers — households that use 5G as a replacement for traditional home internet — who generate more revenue than a typical mobile-only user.

Selling fruits, an expensive affair

Now, let’s move onto the retail side of Reliance’s operations.

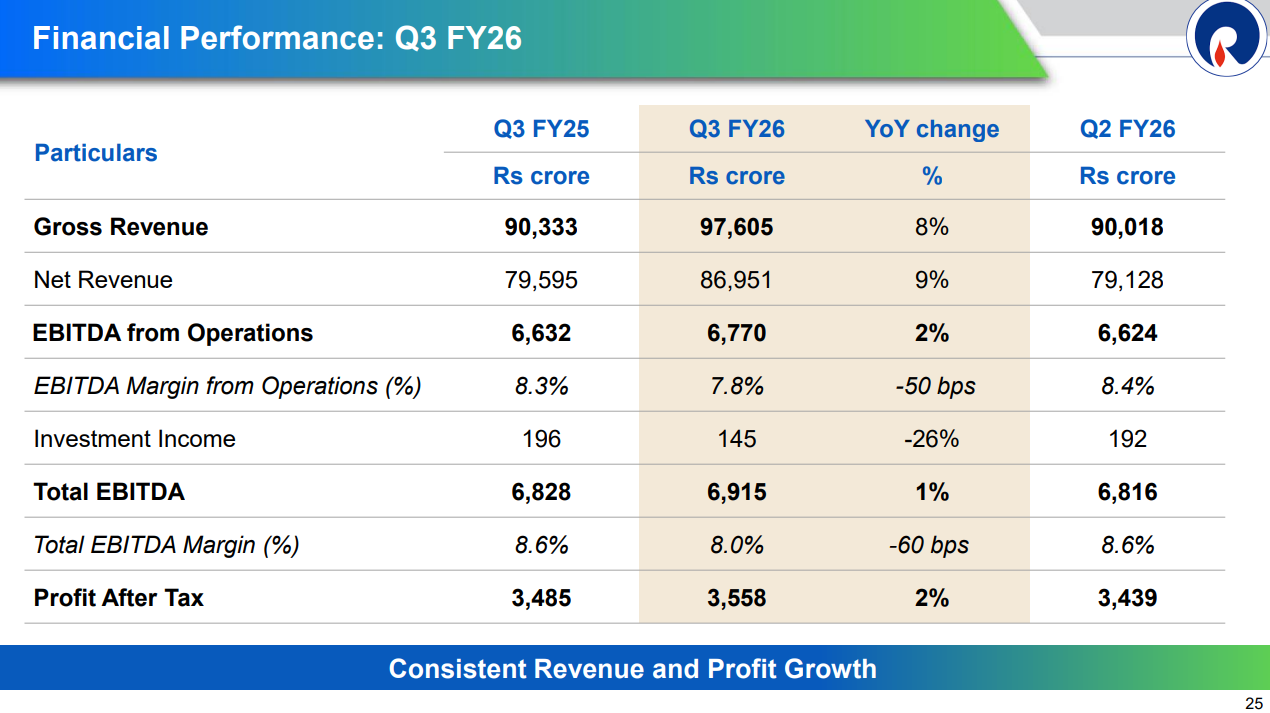

Reliance Retail reported quarterly revenue of ~₹97,600 crore, up ~8% year-on-year. EBITDA, however, was largely flat at around ₹6,900 crore. In simple terms, the retail business is selling more, but it isn’t making much more money.

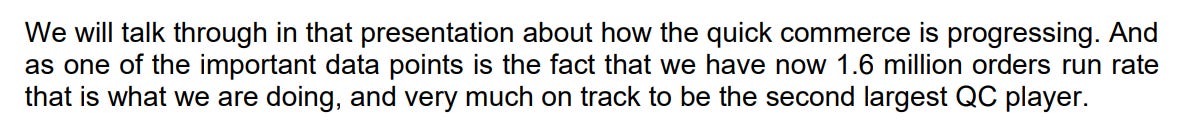

Yet, Reliance Retail continues to spend aggressively. It is expanding its store network, investing in logistics, and pushing hard into quick commerce. Management said its quick commerce operations are now running at around 1.6 million orders a day — on track to be the second-largest quick commerce player in India by volume. Blinkit, the largest player, has about 2.4 mn daily orders.

What is striking is how Reliance’s existing retail network plays a role in driving its q-com business. In q-com, dark stores tend to drive public narrative. But Reliance currently operates around 800 dark stores — accounting for less than 30% of the total fulfilment network. The bulk of q-com orders flow through larger walk-in stores: like your neighborhood Reliance Bazaar or Smart.

Reliance’s q-com business is contribution-margin positive, meaning each order covers its direct costs such as sourcing, packing, and delivery. That suggests the basic unit economics are sound. But overall profitability remains elusive. We’ve covered how Reliance’s q-com playbook differs from other players in more detail on our weekend show: Who said what?

Drill, baby, drill

Let’s move on to the legacy core of Reliance — its energy business.

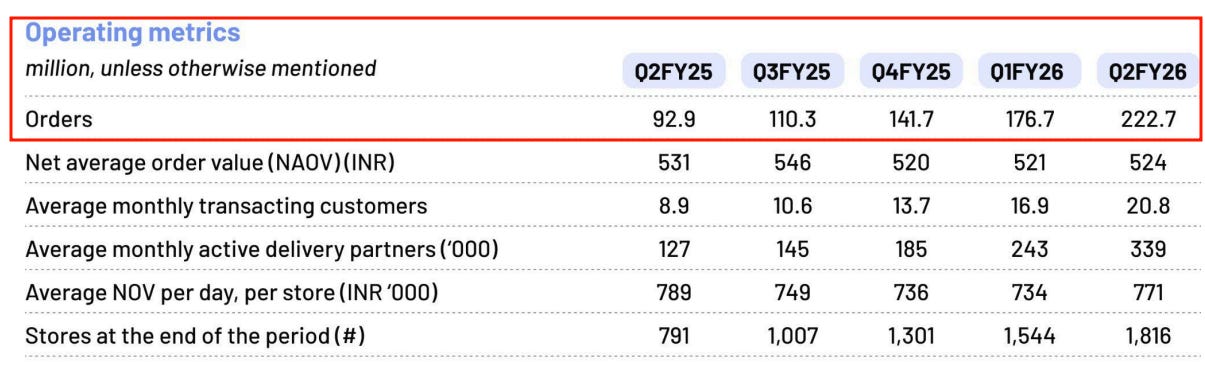

Their O2C line is where the crude oil comes in, and is turned into everything else: like fuel for vehicles, or plastics, or even the materials for textiles and detergents. The O2C business runs one of the world’s largest refineries in Jamnagar.

This quarter saw an extraordinary improvement in the numbers. But this improvement had less to do with internal company productivity, and was more a function of global fuel markets. Refining margins rose because global supply tightened, as several refineries outside India were shut down or disrupted due to maintenance or geopolitical turmoil. Meanwhile, shipping constraints simultaneously pushed up freight costs and limited the availability of vessels.

Efficient refiners like Reliance tend to benefit disproportionately from such a supply squeeze. They can process crude at lower cost than most competitors, and as finished fuel prices rise due to scarcity, that cost advantage translates into fatter margins.

Not everything within the energy business moved in the same direction, though. The petrochemicals segment continued to face pressure, weighed down by weak global demand and oversupply, particularly from China. Chemical prices remain subdued, and higher freight costs have only added to the strain. So, while refining helped lift quarterly energy profits, chemicals acted as a drag.

The new oil

At the same time, Reliance has been plowing money into clean energy, with ~₹8,000 crore of capital expenditure directed this quarter alone. This part of the business contributed little to earnings, which is not surprising given where it stands today. But, Reliance hopes for the New Energy vertical to become just as big as the O2C business, and the spend reflects that.

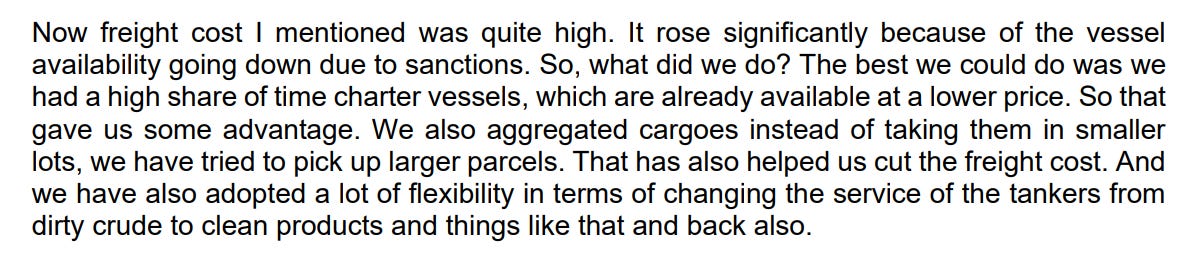

And Reliance isn’t just doing mere power generation, either. The company is trying to set up a fully integrated solar manufacturing chain, covering polysilicon, ingots and wafers, solar cells, and finished modules. It says it is on track to commission a 10 GW annual solar manufacturing facility, with plans to scale this to 20 GW. Module and cell manufacturing have already been commissioned, while pilot lines for ingots and wafers are in place and set to be scaled up during the year.

Alongside this, Reliance is building battery storage capacity of about 40 GWh annually, with plans to expand further. It is also developing a large renewable energy generation project at Kutch, intended to support this ecosystem and supply power internally.

Reliance hasn’t yet offered no clear timelines for when the new energy business will begin contributing meaningfully to revenue or profits. A portion of early output is expected to be used internally, while projects like green hydrogen remain in pilot stages amid uncertainty around pricing and demand.

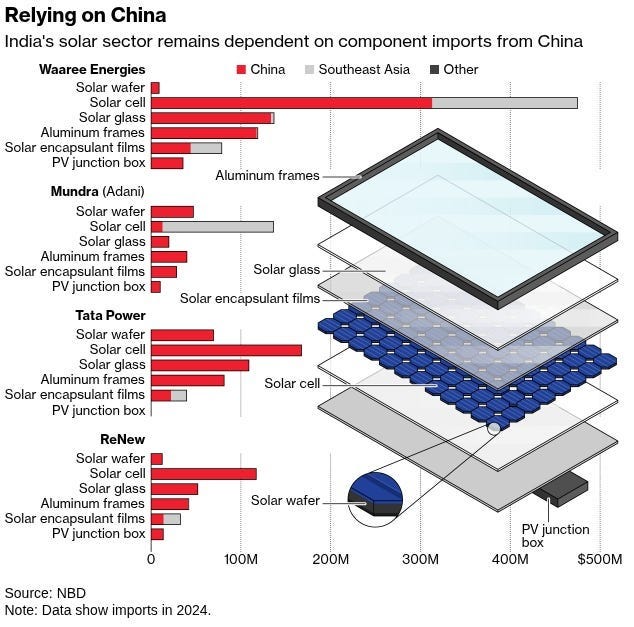

Even then, it is a massive leap for not just Reliance, but India as a whole, as we import many upstream solar components from China. We’ve been trying to indigenize solar supply chains and reduce dependence on China for a while. But, as we covered just yesterday, those attempts haven’t fully successfully materialized yet. This is a big step in that direction.

Conclusion

What you see in this quarter is a company where different parts are moving at completely different speeds. Jio is maturing—growth now comes from getting more revenue per user, not from adding millions of new ones. O2C had a strong quarter, but that had more to do with global refining chaos than any new innovation. Retail is growing but not yet making more money. And New Energy is a bet on a radically different future.

There were a few other things in the results we haven’t spent much time on. For one, advertising spends stayed weak during the quarter, which hurt media revenues, even though viewership on JioHotstar was strong. The consumer brands business, RCPL, also continued to grow, reporting ~₹5,000 crore in quarterly revenue, but this is still a business where Reliance is spending to scale rather than focusing on profits.

These pieces don’t change the big picture, but they do add to the sense of how many different things the company is juggling at the same time.

Tidbits

The Competition Commission has approved the UAE bank’s proposed acquisition of a 51-74% stake in RBL Bank—the largest FDI in Indian financial services and the first foreign bank to acquire majority control of a profitable Indian private bank. The deal still awaits RBI approval.

Source: PIBSetu, Pine Labs’ subsidiary has received RBI approval to acquire 100% of Agya Technologies, which operates the Setu Account Aggregator platform. The move strengthens Pine Labs’ position in India’s open banking ecosystem ahead of its planned IPO.

Source: Economic Times360 One Asset launches ₹1,000 crore fund for defence and spacetech. It has raised the fund entirely from domestic investors, targeting 15-20 investments from early-stage to pre-IPO deals. It has already backed space surveillance firm Digantara, spacetech company Sisir Radar, and Coreel Technologies.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Vignesh and Krishna.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

I am a regular reader of your blog. Wanted to point out some corrections regarding DC current. Statement "DC currents are not suitable for transmission because of losses" is wrong. In fact, DC is better for transmission since it won't have any AC related losses like inductive loss, capacitive loss etc. For a given voltage DC is better than AC for transmission. The problem with DC is it's difficult to change its voltages. Say I supply 25kv dc it's difficult to down grade to lower voltage in the train. Whereas AC can be easily upconverted or down converted to different voltages using transformers. Whether AC or DC at high voltages transmission losses come down drastically.

fascinating to read about electrification of the indian railways.

Would like to read more about the nitty gritty of the trains and the tracks itself. Despite having trains like Vande Bharat designed for 180kmph, because of our poor tracks, the trains are slower.

Upgrading these though a massive infra undertaking will increase our economic productivity reducing travel times. could you please also research and write about the upgrading of tracks, dedicated freight corridors etc?