How power prices work in India

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Problems with how power prices really work in India

The Great Convergence Question

Problems with how power prices really work in India

Last week, the Supreme Court delivered a judgment that reinforced a simple but crucial principle: power companies and electricity distributors can't just sit together and decide the rate at which they will exchange electricity amongst themselves. Each tariff must be approved by regulatory bodies.

What happened was that KKK Hydro Power Limited and the Himachal Pradesh State Electricity Board decided to increase the wholesale electricity rate from ₹2.50 per unit to ₹2.95 per unit in 2010. The problem? They never asked the state electricity regulator for permission. The Supreme Court ruled this was illegal – tariff determination isn't a private negotiation between companies, but a statutory function that requires regulatory approval.

But it brings us to fundamental questions like who is this regulator? How do they set electricity prices? Why is there even a need for this approval in the first place? Does it have any consequences?

Let’s break all of that down.

How is your electricity price decided

India's electricity system works like a three-act play.

In the first act, generation companies produce electricity. These range from massive government entities like NTPC, which runs coal plants across the country, to private solar farms in Rajasthan.

The second act involves transmission companies, primarily Power Grid Corporation of India, which moves electricity across states through a web of high-voltage power lines.

The final act belongs to distribution companies, or DISCOMs, which take that electricity and deliver it to your doorstep. Most DISCOMs are state-owned.

This structure didn't always exist. Until 2003, most states had single government-owned companies that did everything — they ran the coal plants, maintained the transmission lines, and sent you your monthly electricity bill.

The Electricity Act of 2003 changed all that, breaking up these giant state monopolies into separate companies for generation, transmission, and distribution. The Act also created new regulators — State Electricity Regulatory Commissions in each state, plus a central commission for interstate matters — who were supposed to approve electricity prices based on costs and technical analysis rather than political promises.

The theory was straightforward: split up the monopolies, let multiple companies compete to generate electricity, and have independent regulators ensure fair pricing for everyone. Competition would drive down wholesale costs, while regulated distribution companies would pass those savings to consumers.

The wholesale electricity market was designed to work through Power Purchase Agreements — basically long-term contracts between power plants and distribution companies. Think of these as 25-year deals where a coal plant agrees to supply electricity to a state's distribution company at predetermined rates. Today, around 85% of the electricity in India is sold through PPAs.

For older power plants that were already built, regulators would calculate costs using a straightforward formula. The state or central electricity commissions would add up the plant's expenses and then add a reasonable profit margin - the 'cost-plus' system’.

Then came competitive bidding for new power plants. Instead of regulators setting prices, companies would compete in auctions and the lowest bidder would win the contract.This competition could pave the way for cost reductions, especially in renewable energy.

Basically, competitive bidding mainly applied to new capacity additions, while most existing electricity still comes from cost-plus plants. The two-tier system — cost-plus for existing plants, competitive bidding for new ones — meant India's wholesale electricity market became a mix of expensive legacy contracts and cheap new ones.

But here's the catch: even if wholesale prices fell, retail prices for consumers didn't always follow. That's because of how the final piece of the puzzle – distribution – actually works.

Discoms

Distribution companies were designed to function like straightforward middlemen. They'd buy electricity at wholesale rates — some set by regulators, others determined through competitive bidding — and sell it to consumers at retail tariffs, again set by the state regulators.

These prices would ideally be adjusted regularly to keep the prices paid by the end consumer more or less aligned with wholesale costs. When solar power got cheaper, consumers would eventually benefit.

Cross-subsidies were part of the plan too. Cross-subsidization is essentially an internal transfer system where some customers pay above the actual cost of their electricity supply so others can pay below it. Industrial users might pay slightly above cost to help keep residential tariffs affordable, but the system, if it worked right, wouldn't create massive distortions.

Beyond cross subsidies, state governments would handle major policy goals like free power for farmers through explicit budget subsidies. Instead of forcing distribution companies to give away electricity at a loss, the state treasury would directly reimburse them.

That was the plan. The reality evolved quite differently, creating problems across the board.

The cracks

We observed that the SERC is the primary decision-maker on tariffs. When a DISCOM’s costs rise, the sensible fix is to let tariffs rise enough to cover those costs. The real question is how quickly to do it.

Because tariff hikes are politically painful—and subsidies often show up late—regulators use a legal tool called a “regulatory asset.” Instead of approving tariff increases, they would acknowledge that distribution companies deserved higher revenues but defer the actual collection from consumers to some future date.

Suppose a DISCOM in Delhi faced a ₹500 crore revenue shortfall in a given year but couldn't get tariff approval. The DISCOM will be legally allowed to create a ₹500 crore "regulatory asset" — essentially a formal IOU saying consumers would pay this amount eventually, with interest.

The problem is these regulatory assets accumulated interest and kept growing. Nationally, these recoveries reached ₹1.68 lakh crore — money that distribution companies had spent but consumers hadn't yet paid for.

Now add cross-subsidies to the mix. They were meant to be small and controlled, but ended up benefitting individuals a lot. Farmers actually end up receiving the bulk of support—roughly three-quarters of total electricity subsidies.

To make the math work, industrial users paid much more than the actual cost of supply in many states. When high-paying industrial customers face electricity bills far above the actual cost of supply, they tend to start looking for alternatives.

They could generate their own power through rooftop solar. They could also use 'open access' rules — regulations that allow large consumers to bypass their local distribution company and buy electricity directly from any generator or trader. Or they could tap into the short-term market, which follows market based pricing that can be quite volatile. Either way, DISCOMs lose the revenue from highly profitable customers but still had to serve the subsidized customers.

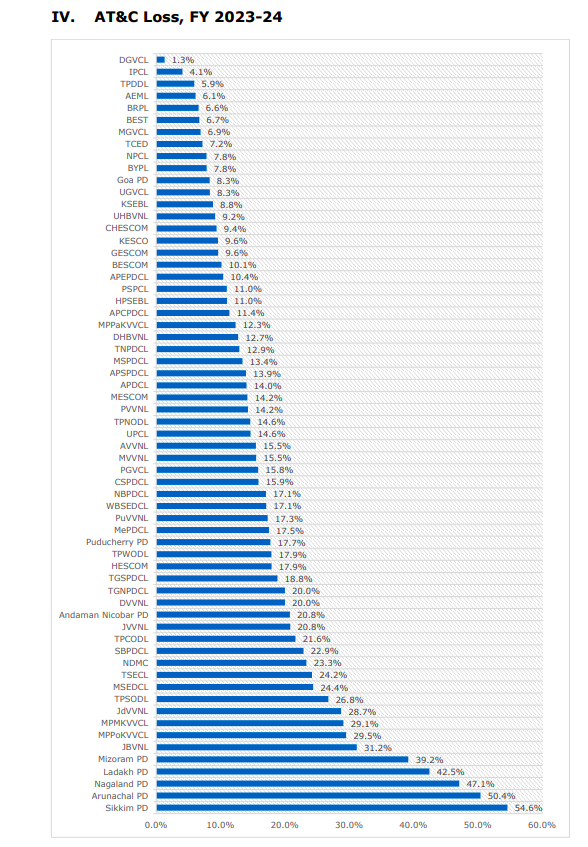

DISCOMS also faced technical losses of about 16% on average – electricity that simply disappears due to theft, faulty equipment, or poor billing.

Ultimately, distribution companies became financially stressed, accumulating ₹6.92 lakh crore in losses in FY24 – roughly equivalent to India's defense budget. And what’s worse is these losses seem to just be growing.

The problem became so huge that the central government launched multiple bailout schemes.

One of the most significant was Ujwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana (UDAY) in 2015, where state governments took over 75% of distribution company debt in exchange for promises to improve operations and reduce subsidies. More recently, the Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS) in 2021 allocated ₹3.03 lakh crore for smart meters and infrastructure upgrades.

Some fixes helped, but the core problem stayed. DISCOMs kept piling up “regulatory assets”—IOUs, not cash. They only turn into money if regulators allow recovery later, and meanwhile they earn interest. Calling them “assets” is generous.

So, in a bid to clean up the finances, in August, the Supreme Court ordered states to clear ₹1.68 lakh crore in regulatory assets within four years. Translation: stop deferring.

What this means is that now it's time for regulators to approve those long pending tariff hikes for DISCOMs so that they could recover the future revenue they are expecting.

Regulators now have to allow time-bound recovery so DISCOMs can collect old dues. As that happens, bills are likely to tick up. Either there will be small surcharges in prices over time, or direct support from state budgets through subsidies. Either way, the gap between what power costs and what we pay has to close.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's recent judgment highlights a fundamental tension in India's power sector. On one hand, there's a legal and regulatory framework designed to ensure fair, transparent pricing. On the other hand, there are political and economic pressures to keep electricity cheap for certain groups.

Caught between the two, DISCOMs bore the brunt—parking costs as regulatory assets, losing high-paying customers, and watching arrears swell.

The Great Convergence Question

I want you to imagine something with me. Picture the world in 2050, just 25 years from now. Will factories in Bangladesh produce goods as efficiently as those in Japan? Will India's economy finally rival that of the United States?

These aren't just abstract questions. They're about the economic futures of billions of people alive today in poor and developing countries. Today we're diving into one of the most fundamental questions in economics: How do poor countries become rich?

The answer, it turns out, is far more complex and fascinating than most economists originally thought.

For decades, economists held onto what seemed like ironclad logic: poor countries should grow faster than rich ones. Think about it. If you're starting from almost nothing, you have enormous room to grow, right? You can copy technologies that already exist, learn from the mistakes of countries that developed earlier, and leapfrog entire stages of development.

This idea, called the "convergence hypothesis," suggested that developing nations would naturally catch up to developed ones. It painted a picture of a world where global inequality was just a temporary phase. It was a beautiful, hopeful theory.

Unfortunately, as we'll discover today, reality has been far more complicated than economists expected.

The Convergence Conundrum

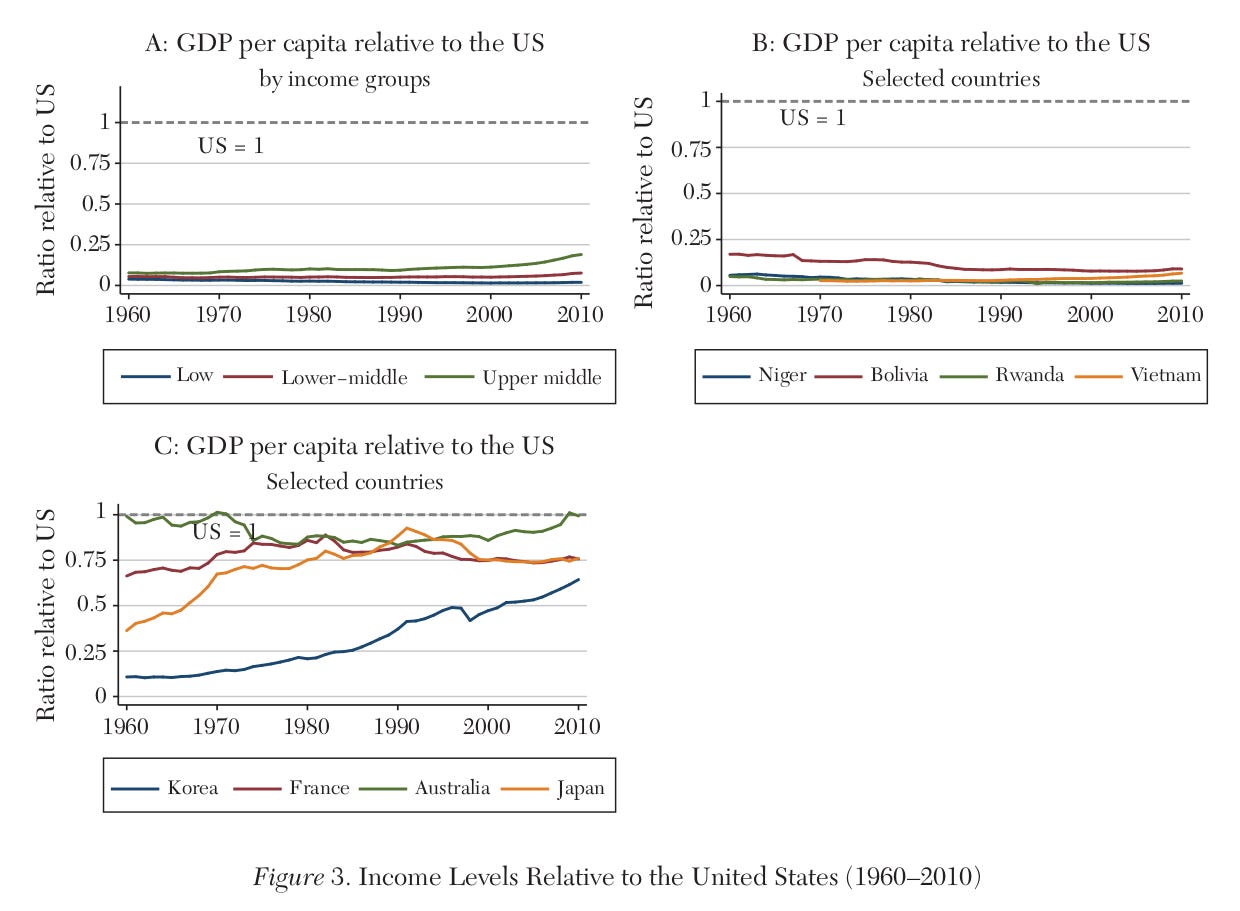

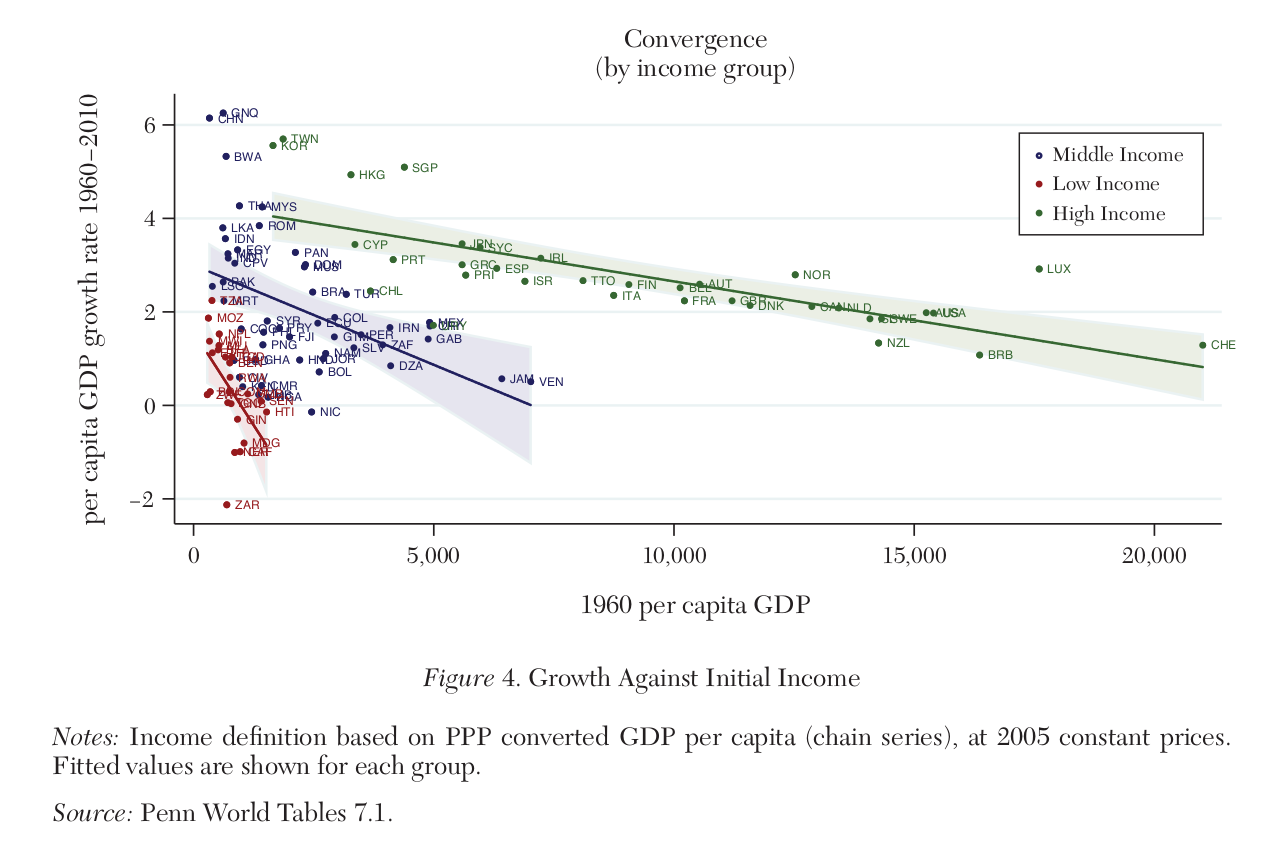

Let's start with the big picture, and it's not pretty. When researchers Paul Johnson and Chris Papageorgiou analyzed data from 182 countries in their comprehensive study, they found there's little evidence that national economies are catching up to their richest peers. High-income countries tended to grow faster than middle-income countries, which in turn grew faster than low-income countries. Even worse, low-income countries actually experienced negative growth rates during the 1980s and 1990s.

"The consensus that we find in the literature leads us to believe that poor countries, unless something changes, are destined to stay poor," one researcher noted.

Instead of poor countries catching up, we've seen what economists call "convergence clubs." These are countries that started with similar income levels in 1960 and still had similar income levels in 2010.

The convergence hypothesis did not seem to be playing out in practice.

But, there’s a catch here. When looking at individual economies, signs of convergence do pop up here and there.

While countries as a whole aren't converging, something fascinating is happening within specific industries. New research from economists at the Bank for International Settlements and the International Monetary Fund shows that manufacturing industries exhibit strong convergence over time.

Industry Matters

Here's what researchers discovered when they analyzed 99 countries across 22 manufacturing industries over four decades: Manufacturing industries that start far behind their global leaders can grow dramatically faster – sometimes seeing an extra boost in growth that's absolutely massive compared to average manufacturing growth rates.

This convergence pattern holds across virtually every manufacturing industry studied. But some sectors catch up much faster than others. Think of it this way: if you're making cigarettes, you'll gradually close the gap with global leaders. But if you're building cars or smartphones, you can catch up almost five times faster.

Why such a huge variation?

Human capital

It was observed that industries that rely more on human capital, that is skilled, educated workers, are driving convergence. Meanwhile, dependence on physical capital like machines and equipment doesn't seem to matter as much. This challenges our typical image of development as being all about factories, machinery, and infrastructure.

Think about the difference between a cigarette factory and a smartphone factory. The cigarette factory mostly needs machines and basic labor—once you've got the equipment set up, you can produce cigarettes without needing highly educated workers. The smartphone factory is completely different. You need engineers who understand complex circuits, technicians who can troubleshoot sophisticated assembly lines, and workers who can read detailed manuals and adapt when problems arise.

The research shows that industries requiring highly educated workforces—like making chemicals, advanced machinery, and communication equipment—catch up with global leaders much faster than industries that rely mainly on manual labor, like textiles or food processing.

When you're trying to adopt cutting-edge manufacturing techniques, you need workers who can understand, implement, and improve upon those techniques. A highly educated workforce can absorb and adapt new technologies much faster, read technical manuals, troubleshoot complex problems, and even innovate on existing processes.

This suggests the path to catching up isn't just about building more factories – it's about building more capable people. Countries investing in education and skills development are seeing their industries close the gap with global leaders.

But is human capital alone a defining factor in deciding what industry would drive a country’s economy towards convergence? Not really.

Sometimes there are other limiting factors too stopping few industries from reaching their full potential.

The Finance Factor

Industries that need massive, expensive equipment—think steel mills or oil refineries—can catch up rapidly, but only if the country has a sophisticated financial system.

Picture this: You want to build a steel mill, which requires enormous, expensive machinery. In a country with weak banks and limited capital markets, these industries actually fall further behind global leaders over time. They simply can't get the huge loans needed to buy modern equipment.

But in countries with well-developed banking systems—think South Korea or Germany—these same heavy industries can catch up rapidly because they can access the capital they need. The difference is stark: steel and chemical companies in financially underdeveloped countries keep using old, inefficient equipment, while their competitors in countries with good banks get state-of-the-art facilities.

This explains why some countries struggle despite having the "right" industries. You might have raw materials and basic infrastructure, but if your financial system can't channel capital efficiently, those capital-intensive industries remain stuck.

The Development Path Matters too

The path of development too shapes convergence. As economies shift from agriculture to industrial and service sectors, they rely more on human capital. Since human capital-intensive activities converge faster, this structural transformation drives overall economic convergence.

Look at the success stories: Vietnam was among the world's poorest countries in the 1960s, but by the 1990s it had become one of the fastest-growing economies globally. How? By moving millions of workers from rice paddies into factories making textiles, electronics, and other manufactured goods. Bangladesh followed a similar path, transforming from an economy in decline to steady growth through manufacturing.

Meanwhile, China's transformation is perhaps the most dramatic example. In the 1960s, China actually had negative economic growth. But by focusing on manufacturing and moving workers from agriculture into factories, it became the world's fastest-growing major economy.

Here's why this matters: Countries where most people work in factories and offices will close the economic gap with wealthy nations about twice as fast as countries where most people still work on farms.

This explains why some countries with apparent advantages still struggle while others surge ahead. It's about the timing and speed of moving people from agriculture to manufacturing and services.

What This All Means

So where does this leave us? The picture that emerges is complex but hopeful. While overall country-level convergence has been disappointing, we now understand why—and more importantly, we understand what works.

The composition of the economy matters enormously for convergence. Within manufacturing, industries that rely heavily on skilled workers catch up faster with global leaders.

Countries need to focus on three things simultaneously:

i) building human capital through education and training,

ii) developing robust financial systems that can channel capital efficiently, and

iii) encouraging the growth of industries that can make the most of both

But here's a crucial insight from the research that helps explain why convergence has been so elusive: economic growth in developing countries isn't smooth and predictable. It's what economists call ""episodic"—characterized by sudden bursts of rapid growth followed by sharp declines, often leading to economic disasters.

The data reveals something striking: a country's growth rate in one decade is almost completely useless for predicting its growth rate in the next decade. In fact, for low-income countries, the correlation between growth in consecutive decades is essentially zero—sometimes even negative. This means a country that grows rapidly for ten years might suddenly find itself in decline for the next ten years, wiping out much of its progress.

This stop-start pattern helps explain why so few countries have successfully converged with wealthy nations. Even when countries get the fundamentals right and start growing rapidly, they often can't sustain it. The countries that do succeed—like South Korea and Vietnam—are the rare ones that manage to maintain favorable conditions across multiple decades, avoiding the economic disasters that derail so many others.

The Bottom Line

Poor countries can catch up, but only if they get the fundamentals right AND sustain them over time. The countries that understand this, that invest in their people while building modern financial systems and fostering the right kinds of industries, those are the countries that will close the gap with wealthy nations in the coming decades.

Tidbits

Dreamfolks recently announced that three of its customers, including the country's third-largest lounge operator, Encalm Hospitality, would end their contracts with them. Adani Digital and Semolina Kitchens will also terminate their contracts. This comes months after the CEO shared they faced pressure tactics by two large airport operators, who have entered the same line of business.

Source: Reuters

India remains the world’s fastest growing economy, as China’s GDP growth rate in April-June came in at 5.2% and United States’ at 3.3%, after the latest data released. India’s economy unexpectedly expanded 7.8% year-on-year in the April-June quarter, picking up from 7.4% in the previous three months.

Source: PIB

A ban on money-based online games may cause huge losses for broadcasters and rights holders who relied on fantasy sports advertising. Sponsorship deals are already affected. The Board of Control for Cricket in India seeks a new sponsor for the Asia Cup.

Source: ET

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Prerana and Bhuvan

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Thank you for the interesting, well written and easy to understand content - not easy to get all the 3 right every time!