How much are Indians buying: A story told through con-calls

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Have Indians stopped buying?

India needs more women on its factory floors

Have Indians stopped buying?

How much are Indians consuming?

If you’re trying to understand the economy, this is perhaps one of the most important questions you can ask.

See, an economy might seem like an abstract concept, but behind the jargon, it's just money changing hands again and again. There are a lot of flashy things that happen in any economy — foreign companies set up state-of-the-art factories, governments pull off giant highway projects, industries turn into world-beating exporters, and more.

The beating heart of an economy, though, is simple. It’s regular people paying each other. When you buy breakfast, pay for a haircut, or spend on a pair of shoes, that's the economy in action. In India, all this everyday spending — what economists call “consumption” — makes up about 60% of our economy. The more people spend, the faster money flows, and the better the economy runs. And so, “how much are Indians consuming” is a massively important question.

Only, it’s a really hard one to answer.

What do the people of India think?

There’s no perfect way of measuring consumption.

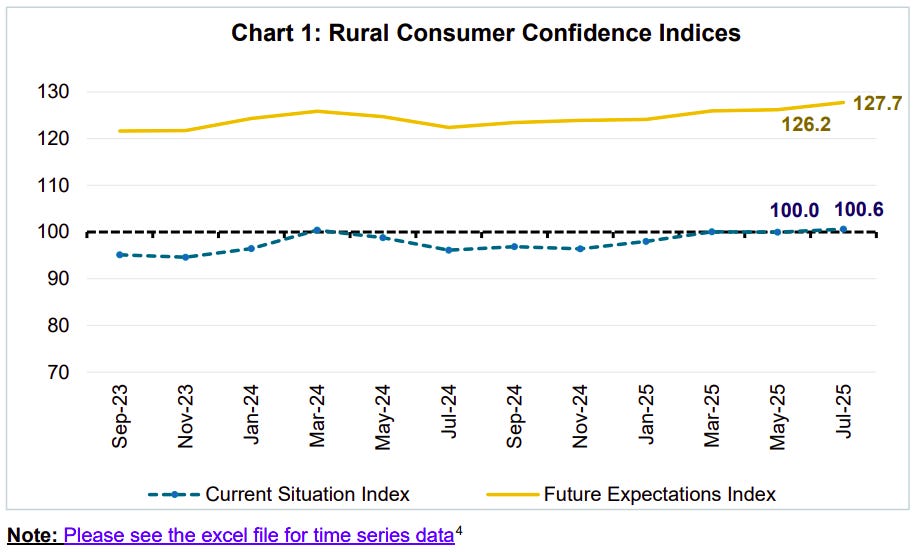

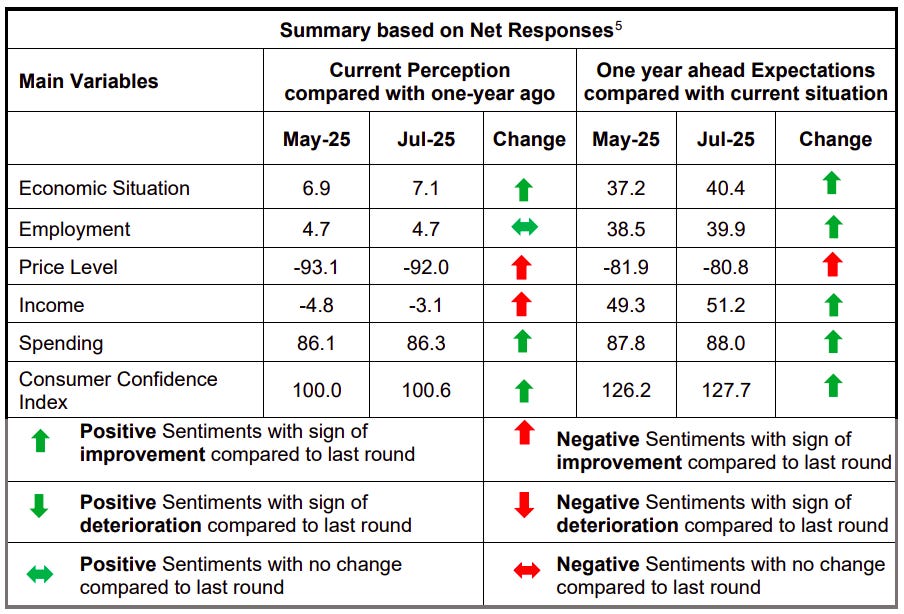

But one quick-and-dirty way is to look at RBI’s rural and urban consumer confidence surveys. The RBI basically asks households how they feel about the economy, jobs, prices, their own income, and spending.

Through this, it tries to understand two things: how the present day compares to last year, and how they feel about the next 12 months. These answers are boiled down to two numbers: the “Current Situation Index (CSI)” and the “Future Expectations Index” (FEI). A score above 100 points to optimism, one below 100 signals caution.

As per its latest rural survey, rural Indians feel somewhat upbeat at the moment: with a CSI of 100.6. They’re also much more hopeful about the year ahead, with an FEI of 127.7.

Villages are especially positive about jobs. And they’re signalling that they’ll spend more on both essentials and “extras”.

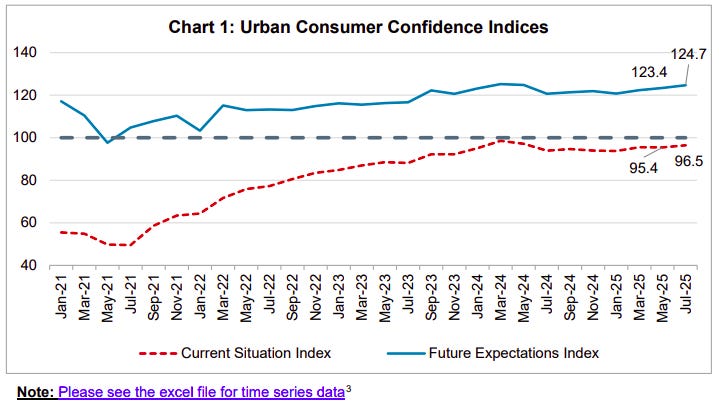

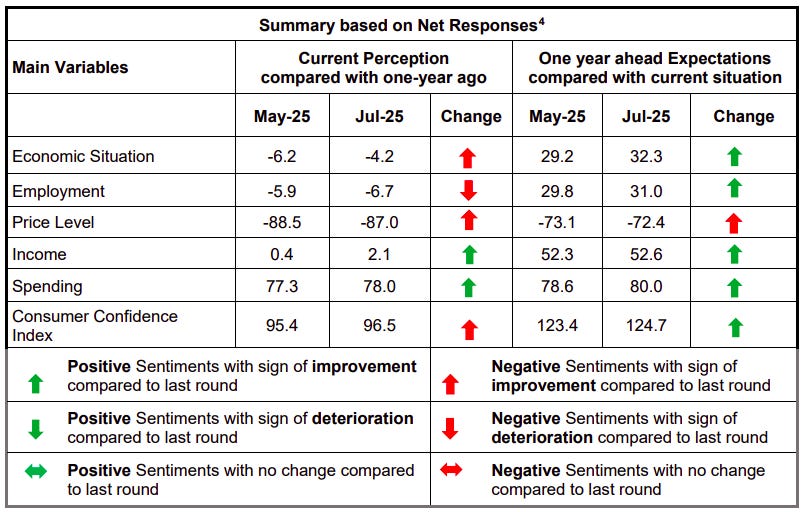

Cities, however, tell a different story.

Urban India’s CSI, however, is under the 100 mark, at 96.5. People, in short, are somewhat disappointed about how things are going.

They’re more upbeat about their incomes than rural households, but less confident about jobs. And while they’re still spending, they aren’t keen to splurge on non-essentials.

That said, they’re hopeful about the future, with an FEI of 124.7. But life doesn’t look great right now.

How do India’s leading companies see this?

These indicators, however, have their limits.

For one, they tell you about consumption as one big headline number. But that hides a lot of complexity. After all, consumer confidence figures are essentially an average of hundreds of millions of very different lives. But no household is actually “average.” Each is shaped by its own income, location, obligations, and hopes. Two families living on the same street can feel very differently about the economy.

This is crucial for a business. Your fortunes don’t rise and fall with “India’s” collective mood, but that of your particular customers in your target market. And those micro-stories can diverge sharply from the national picture.

So another quick-and-dirty picture comes from companies’ earnings calls. They’re messy, anecdotal, and far from perfect. But they’re a quick way to pick up on a lot of these divergences. When CEOs talk to investors, they often end up revealing what’s really moving (or stalling) demand on the ground. These aren’t perfect, but they do give you an idea of what’s happening, directionally. This is our attempt to piece that together.

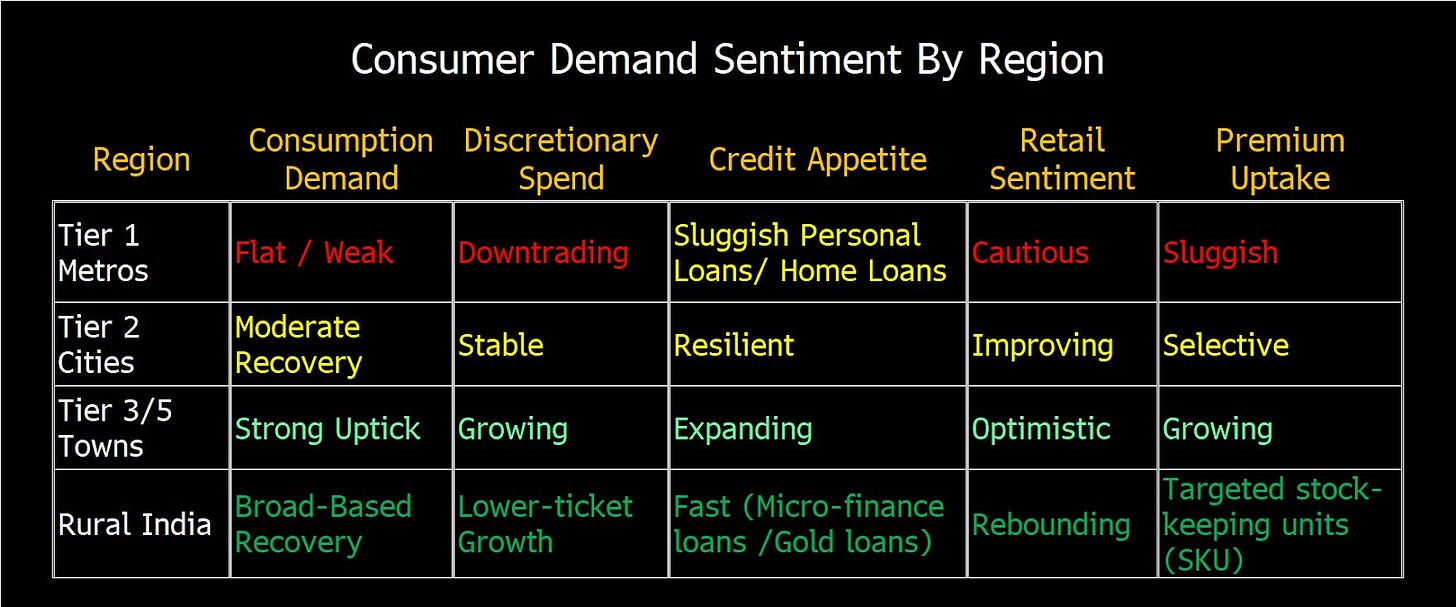

Before we begin, though, for an excellent summary of what they’re saying, check out this chart by Nitin Chanduka from Bloomberg:

The monsoon changed everything

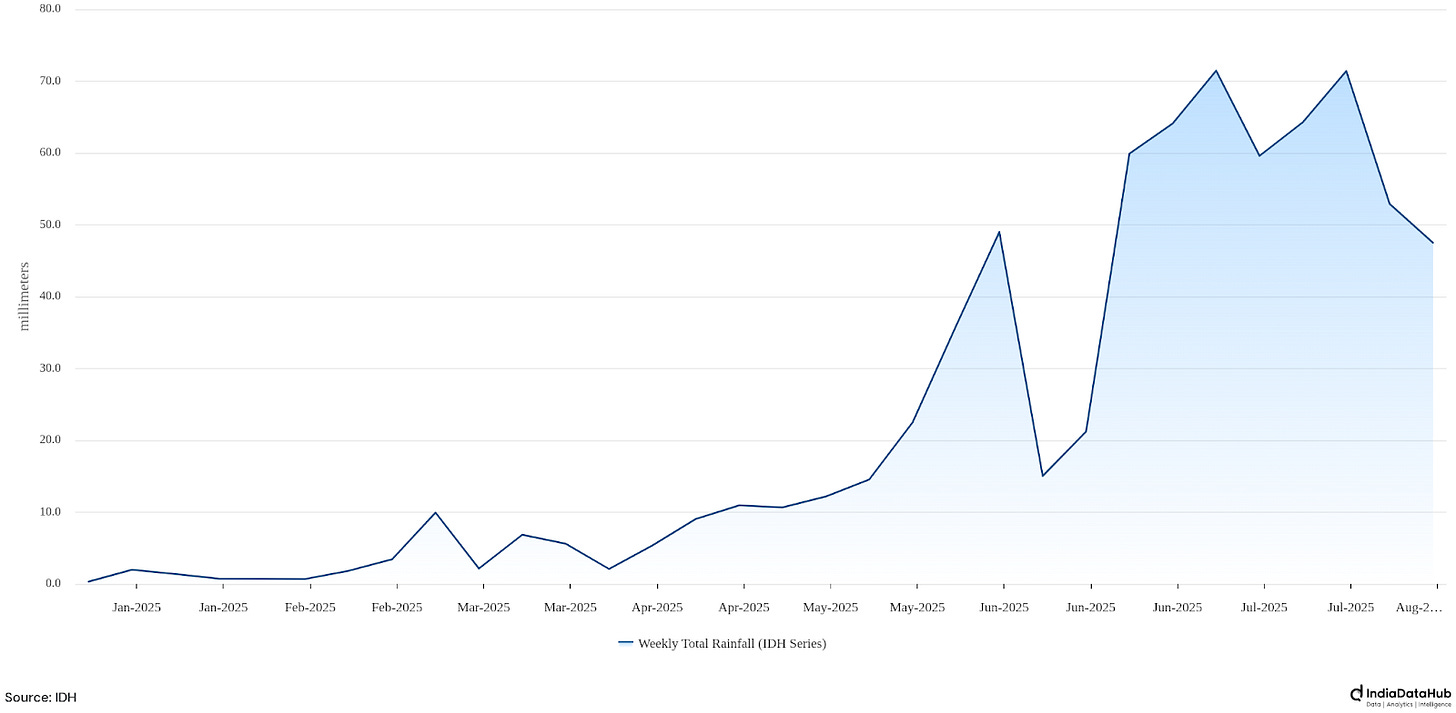

India's economy was thrown off by the rains this year. The monsoon came in May instead of June. That single month changed everything.

See, in most years, April and May are brutal. Temperatures regularly hit 40-45 degrees. Everyone's running coolers, ACs and fans 24/7, and many companies plan their calendars around that fact.

Power plants gear up for the surge. Appliance stores stock up on cooling products. Paint companies schedule their biggest projects for the dry season. Even beverage companies gear up for heat.

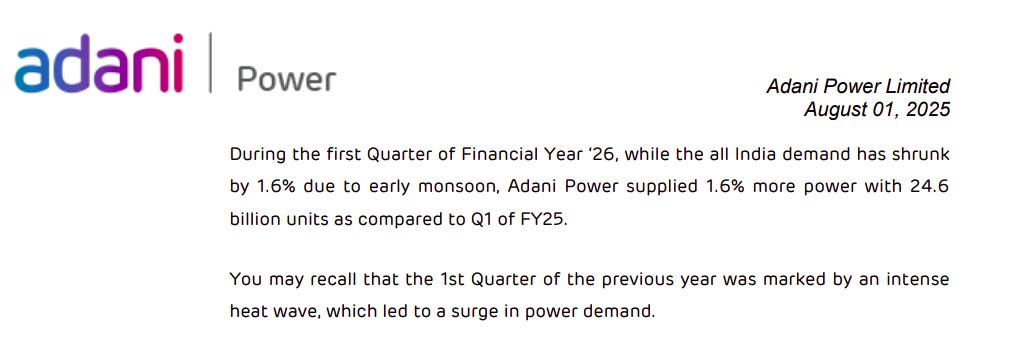

But this year, it started raining instead. Adani Power's CEO captured what happened next:

“During the first Quarter of Financial Year ‘26, while the all India demand has shrunk by 1.6% due to early monsoon”

So power demand fell. But that isn’t all.

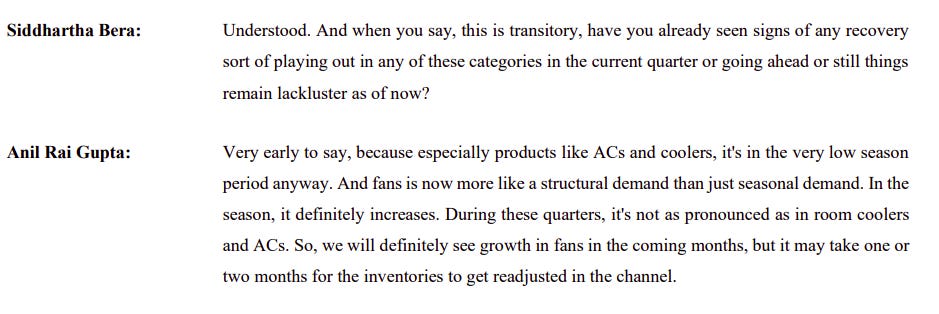

If people aren't using electricity for cooling, naturally, they aren’t buying coolers either. Havells, one of India's biggest appliance companies, landed up with warehouses full of coolers nobody wanted. Their CEO admits they need "one or two months" just to clear all that extra inventory.

Asian Paints faced the same problem. People usually paint houses before the monsoon, when it's dry outside. But when it started raining in May, many of those projects were stalled.

What does this mean, in the long run?

Across sectors, dealers were stuck with stock they bought as early as March. All that working capital got locked up; stretching what they could spend the next season.

But this means different things for different companies. For some, those purchases simply won’t materialise this year. For others, that demand just got postponed. Someone renovating their house, for instance, might just wait out the monsoon before starting again. Which is why many companies are sanguine, hoping for a bounce-back in Q2.

Rains are a rural bonanza

At the same time, rains also bring good news: especially for rural India. When the rains are good, water tables are full, and crops do well. For one, that brings comfort to anyone in agriculture. Meanwhile, rains push down food prices, so everyone’s cost of living drops.

Meanwhile, the government’s been pumping in money: MSP, direct transfers, and more.

All of this adds up. Rural India was already doing better than urban India, and that continued. As Dabur's CEO noted, rural markets have now outperformed urban ones for five straight quarters.

HUL echoed this sentiment: “...the consumption environment remained stable, with rural demand continuing to grow ahead of urban demand.”

But cities are another story. As HDFC Bank said, there's "a little bit of fatigue" in urban premium consumption.

India’s split car market

Auto sales are usually a fantastic barometer for the economy. Think about it: nobody buys a car if they aren’t confident about their future. If Indians are buying more cars, it probably means they’re feeling good about their medium-to-long term prospects.

That isn’t happening right now, though.

As Maruti Suzuki’s management noted, sales across the auto industry shrank 1.4% last quarter. A lot of that pain was concentrated in entry-level cars — Altos, WagonRs, and other cars that, so often, are a family’s first vehicle.

To Maruti Suzuki, “The affordability issues in the entry segment cars continue to affect the growth of the industry”

Meanwhile, the SUV market now makes up 55% of all sales.

Indians, it seems, have splintered into two groups. Those who can buy a car are going straight for an SUV, and all the bells-and-whistles that come with one. Those who can’t — who would otherwise buy an entry-level car — aren’t buying anything. The middle is missing.

It’s not that Indians aren’t obsessing over running costs any more, though. As Maruti said: "Every one in three cars sold by the Company in the domestic market was a natural gas vehicle."

That’s a fascinating portrait of the Indian consumer in 2025 — aspirational, yet cost-conscious.

This also shows up in two-wheelers. TVS, for instance, talks about 'scooterization' — people who might once have bought a moped are now upgrading to scooters.

But let’s go back to an older point. There’s one sort of automobile that points directly to rural demand: tractors. Tractors are a huge purchase, but with just one target customer: farmers. They point, purely, to rural purchasing power. And that is doing very well. As Mahindra's CEO said: "Rural sentiment is better and we're seeing that in our Tractor business. Urban continues to be weak."

Rural India, it seems, really is in good shape.

The credit system is nervous

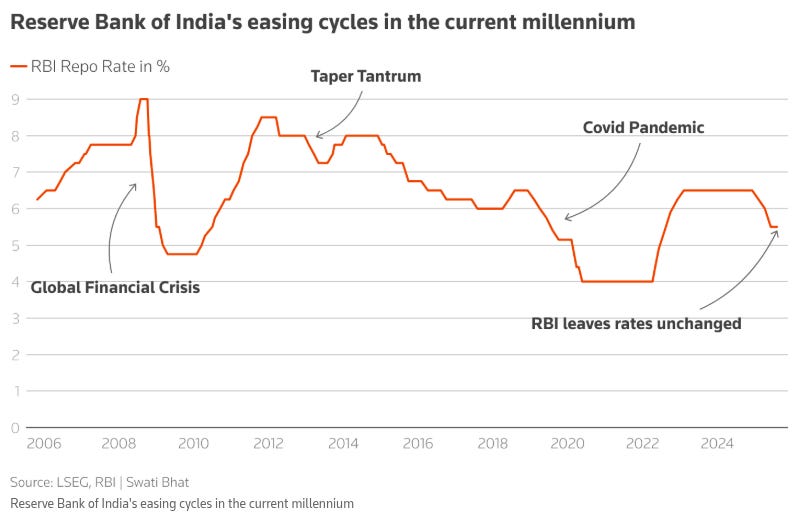

Money’s the cheapest it's been in years. After a prolonged period of high interest rates, the RBI cut rates by a full percentage point this year.

These cuts came at a time of strong corporate balance sheets. Businesses were well-positioned to borrow. If the economy was running hot, this would be like pouring fuel on a fire. Lending would explode; confident consumers would rush to buy things on credit; while businesses would borrow to expand.

But, instead, as Kotak’s management said: "The cut in interest rates have not yet stimulated demand for Bank credit."

Banks, meanwhile, seem scared. They're beginning to see stress build up in their portfolios, and they’re thinking very hard about who they should lend to. SBI Cards, for instance, said "quality acquisition is primary" — they're rejecting more applications than they're approving.

Imagine you run a small business, and nobody’s willing to lend to you. What do you fall back on? Your family gold, of course.

That’s precisely what’s happening. IIFL Finance, for instance, says gold loans are at all-time highs. As they explained, MSMEs who "were reluctant to pledge their gold earlier now have no other funding source." On top of that, gold prices are spiking, and your gold can fetch you 50% more money than two years ago.

This points to a lot of nervousness in our financial system. When a small business needs 5 lakhs urgently, right now, they're taking their wife's jewelry to the gold loan company.

The real problem

Here’s the heart of the issue, as Mahindra's CEO pointed out: "The fundamentals are strong... But at this point, [sentiment] is weaker."

He might have a point.

There’s a lot to be happy about in our economy. We had a great monsoon. Rural incomes are rising. Credit is cheap. Inflation is down. The government is spending. Companies have healthy balance sheets. By every measure, India should be booming.

But it's not.

Our confidence, it seems, has collapsed. Take businesses: they’re sitting on large treasuries, but won’t invest in new factories. As Kotak noted, despite "healthy corporate balance sheets," there's no "momentum in private capital expenditure." Why build a new plant when you're not sure you’ll find any buyers?

Is there hope?

Practically every CEO we saw, from banks to cars to FMCG, was fixated on one thing: the festive season. HDFC Bank's CEO laid out a whole timeline: Onam in August, then Ganesh Chaturthi, building up to Navratri, with Diwali providing the grand climax. He thinks "that mood will have a reasonable amount of impetus."

Are they on to something? Or is this wishful thinking? We’ll know soon enough.

This is all just one interpretation

As we told you before, though, these con-calls make for a quick-and-dirty indicator. And you shouldn’t trust them completely.

A few weeks back, Rajeev Thakkar, CIO at Parag Parikh Mutual Fund, took a completely contrarian position. As he said: “Let me argue that there’s no consumption slowdown.”

As he argued, people haven’t stopped spending — they’re just spending elsewhere. Every time a company sees flagging demand, perhaps there’s someone else eating at their business.

Every sale by a niche direct-to-consumer shoe brand, perhaps, is one less order for a listed retailer. Every IPL ticket sold, perhaps, is an empty multiplex seat. Every biryani sold on Swiggy is a packet of Maggi that had no buyer. And so on.

So, is all that we said just… wrong? Is he right? We don’t know.

There’s a reason people think investing is hard.

India needs more women on its factory floors

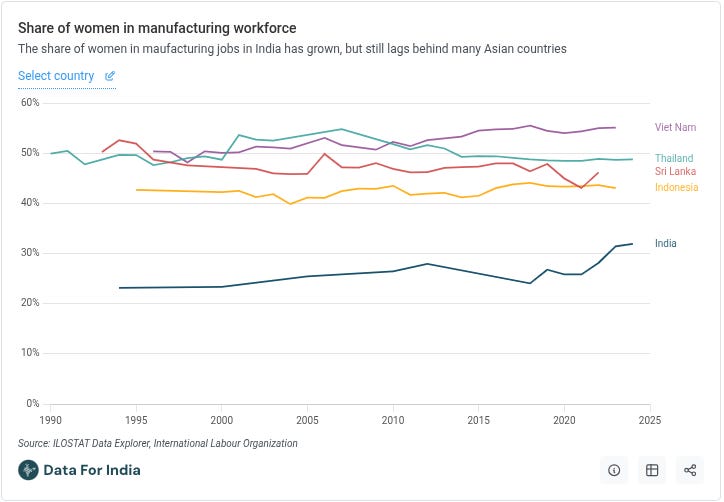

Every rich country in the world has taken a different path to getting rich. But they all share one common factor: a robust manufacturing sector, which employs lots of women. That is even true, in fact, of countries that are currently charting their way to prosperity. In Vietnam, for instance, more than 50% of the manufacturing workforce is women. Indonesia hovers around the 40% mark.

India, however, lags far behind. Women only became 30% of our workforce two years ago by some estimates. By others, we aren’t there even now.

This isn’t just a matter of promoting diversity for the sake of it, by the way.

We're running like a plane flying with one engine switched off. While we fuel lots of money into building a manufacturing engine, if a huge portion of our workforce is sitting at home, there’s only so far it can go. And since we’ve just spoken so much about consumption, think about this: if most Indian workers are also providing for the women of their household, how much more careful might they be about spending their paycheck?

Across the world, the entry of women into shop-floors has been crucial to economic development. And that’s possible for us too. The World Bank, for instance, estimates that with greater female participation, India's manufacturing GDP could potentially increase by 9%. That's billions of dollars we’re leaving on the table.

We recently came across reports by ICRIER and Data For India, which got us thinking about this problem. Here’s what we learnt.

Stuck in low-value jobs

To understand why more people aren’t coming into the workforce, it might help to understand the lives of women who are already there. Because most of India’s female manufacturing workers are stuck in menial, low-value jobs.

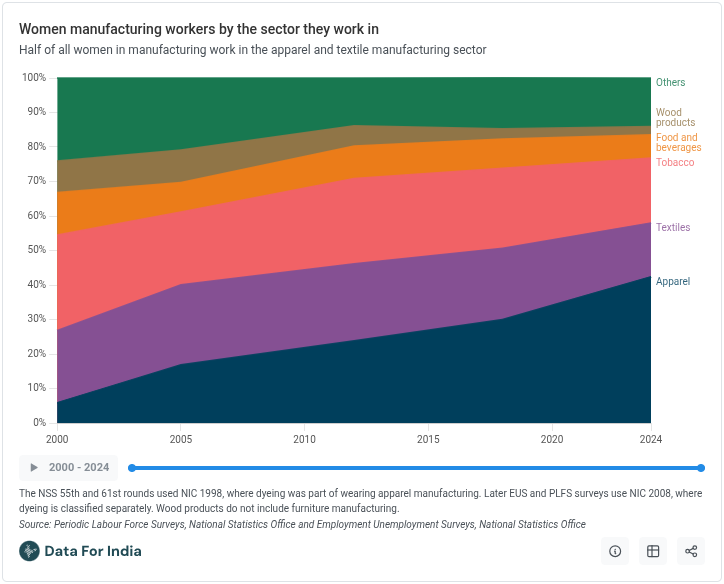

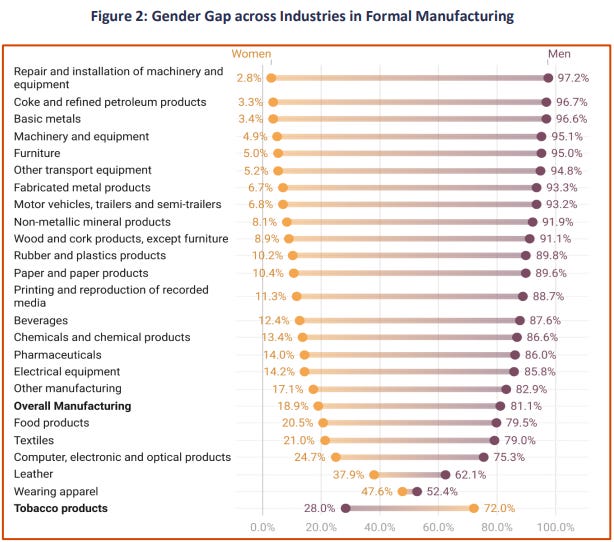

See, manufacturing includes making a variety of things: from clothes, to aircraft. Some of those (aircraft, electronics, machinery) are complex to build, and therefore pay well. Others (bidis, apparel, food) are not that complex, and therefore not too high-paying. The more complex goods a nation makes, the richer it gets — something we’ve covered before.

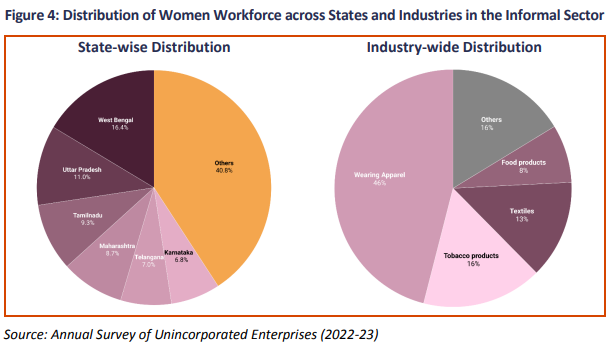

Now, India does make goods with high complexity. But women are hardly involved. In fact, 78% of all women in manufacturing are concentrated in four low-complexity sectors: tobacco, textiles, apparel, and food products.

Consider the task of rolling bidis. This is something that adds little value, and pays workers just ₹29,000 a year — less than half the national manufacturing average. 93% of this workforce is female.

The picture reverses once you look at more complex, high-paying industries. In equipment manufacturing, for instance, women are just 4.9% of the workforce.

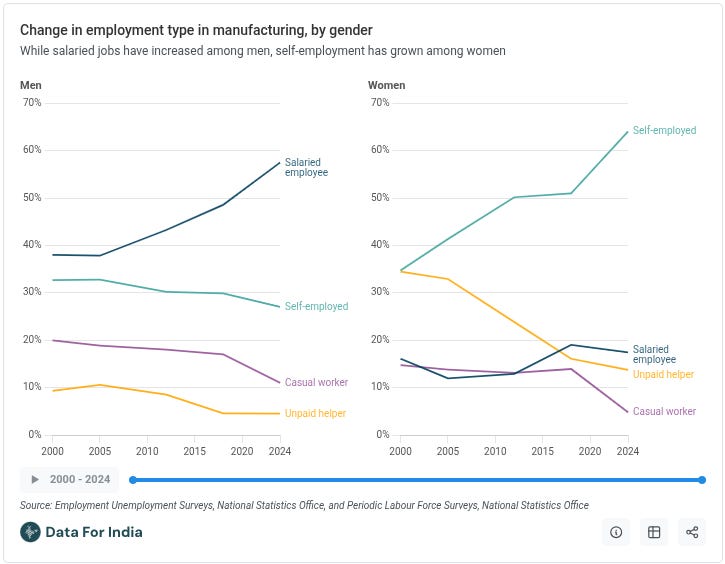

This is compounded by yet another pressing issue: informality. Even (and especially) in industries where they dominate, women mostly occupy informal jobs. These jobs come with little economic stability, and they lack formal contracts, social security, or labour protection. Consider this: 9 of every 10 women in Indian manufacturing have informal jobs. For men, that figure is much lower – 66%. And this has been stagnant over the last few years.

Think of women that sit at home and stitch footballs in their spare time. Or those who make paapads for small-time brand. That is what most Indian women in manufacturing look like.

Over 60% of them, in fact, are classified as "self-employed". But don’t make the mistake of confusing that with entrepreneurship — as we’ve covered before, a vast majority of India’s “self-employed” workers are simply trying to get by outside any formal structure. They have low productivity, and are extremely insecure.

That problem persists even in the organized sector. Most women are employed in factories, in reality, work under conditions that are quite similar to informal jobs, without long-term contracts, social security, or so on.

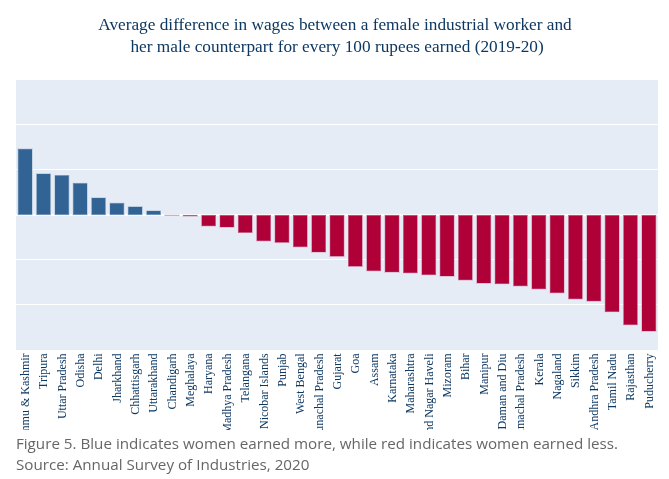

All of this directly hurts women’s wallets. In 2019-20, for instance a female industrial worker made only ₹382 per day, while men earned ₹439 per day.

Life, in short, is hard for women in India’s manufacturing sector.

Geography matters, a lot

This story, however, looks very different as you move through different parts of our country.

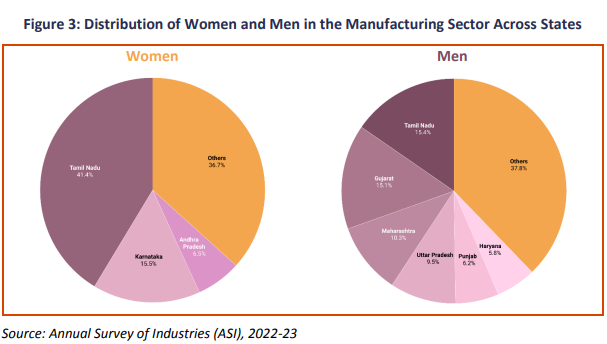

Most formal manufacturing jobs for women are located in South India. Just three states — Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh — account for 60-66% of all women in India's formal manufacturing sector. Tamil Nadu alone employs an impressive 43% of India's entire formal female manufacturing workforce.

This edge isn’t entirely accidental. Many of India’s recent manufacturing wins have been focused in this small cluster. This is because these states offer companies a cheap, well-behaved, well-educated workforce. This is possible, in part, because of how many women it has — the outcome of years of long-term investments in women’s education and housing.

Women in informal manufacturing, meanwhile, belong to a very different belt. Here, West Bengal leads with 16.4% of informal female manufacturing workers, followed by Uttar Pradesh at 11%. Tamil Nadu, though, is third here as well, accounting for 9.3% of women’s informal manufacturing jobs.

In other words, when we talk about Indian women in manufacturing, we’re actually talking about two parallel economies with weak bridges between them. One is the economy of formal, high-value in South India — woman assembling cars on a Hyundai factory floor, or making phones for Apple. The other is more informal, low-value and geographically dispersed — like someone that makes cheap bangles.

From village to factory floor — and back

Perhaps what you take away, from this, is that we need many more women in the sorts of formal factories you find in South India’s industrial belt. But to understand how hard that is, try visualising the countless hoops women have to jump through to get there.

Imagine you're a 22-year-old woman from a village in Bihar who wants a factory job in Tamil Nadu. Your battle begins at home.

For one, there are strong cultural barriers to women stepping out of their homes to work. Many households, in fact, see it as a matter of pride that their women don’t work.

But on top of that, women in Indian households face what researchers call "time-poverty." They often handle a range of household chores — childcare, cooking, cleaning, and caring for elderly relatives — leaving little time for paid work. This becomes a drag even for women that do work. In fact, this is a reason often reported for why, in factories, women finish their work faster than men.

If you do get out of home, though, there’s a skill gap. Women often don’t have the skills to take up higher-paying technical jobs, nor do they have avenues through which they can develop those skills. This narrows their prospects to just basic sewing and packing roles. This shows in the statistics — only 6% of women in manufacturing have any kind of formal vocational training.

The hiring practices of companies make this worse. Foxconn, for instance, flatly refused to hire married women for their factories, assuming that they would have too many family responsibilities.

If you do find a job you’re suited for, infrastructure becomes the next hurdle. To hire women, companies need to make a lot of investments: in everything from creches, to outdoor lighting, to bathrooms, to rest areas, to transport. Often, you also need to set up dormitories.

Many companies simply don’t invest in these. And without that, life can be really hard. Here’s one statistic: just 21% of factories in India have designated sanitation facilities for women. Often, women cope with this by not drinking any liquids before going to work.

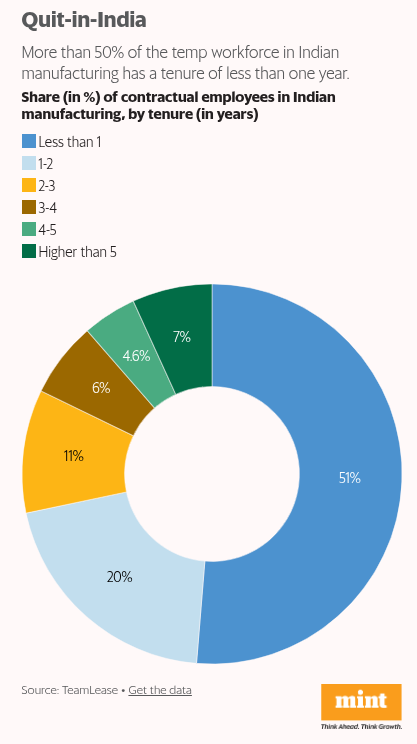

This is just a small list of barriers. It is not nearly comprehensive. What do you do when you face so many hurdles? Well, many just quit. Which is why Indian manufacturing companies see high attrition rates for women.

Fighting inertia

We know we’ve painted a dark picture. But there’s a lot we can do to get around them. And a lot is already being done.

Governments, for one, are trying hard to break this cycle of stagnation, by investing in women more. Karnataka's “Shakti” scheme, for instance, offers free buses for women. That one step, alone, led to a 23% increase in women's employment in Bangalore. Odisha's MSME Development Policy, similarly, offers 100% reimbursement of employer contributions to EPF for female workers, compared to 75% for male workers.

The private sector hasn’t been sitting idle, either. Foxconn, for instance, partnered with the Tamil Nadu government to build a massive dormitory to house mostly working women. Shahi Exports, India’s largest garment exporter, offers women to-and-fro transport, as well as childcare facilities. For Schindler India, 50% of their entry-level campus hiring is reserved for women. Industry bodies expect moves like this to increase more women in the workforce, while also reducing attrition rates for existing employees.

Ultimately, we need many more such investments for more women to enter manufacturing. These are, indeed, difficult problems to solve. But with billions of dollars on the line, the consequences of not doing so might be even harder to deal with.

Tidbits

The Gensol Group’s crisis just deepened — four former executives allege the company deducted tax from salaries for a year but never deposited it with the authorities. That leaves ~2,200 ex-employees potentially liable to pay the same tax again, as the Income Tax Act holds employees responsible even if the employer defaults.

Source: Mint

Tilaknagar Industries (TI) has delivered a stellar Q1 FY26, with net revenue up 30.6% YoY to ₹409.1 crore and PAT (ex-exceptionals) surging 120.8% to ₹88.5 crores. TI's board approved a ₹59 crore investment to expand Prag Distillery’s bottling capacity six-fold in Andhra Pradesh, enabling it to meet nearly half of the state’s demand for TI brands.

Source: Business Line

Motilal Oswal Financial Services has invested ₹400 crore in quick commerce firm Zepto as part of a larger ₹1,000 crore fundraising round. The investment aims to generate long-term returns, with additional funds coming from domestic investors and Zepto’s founders.

Source: Money Control

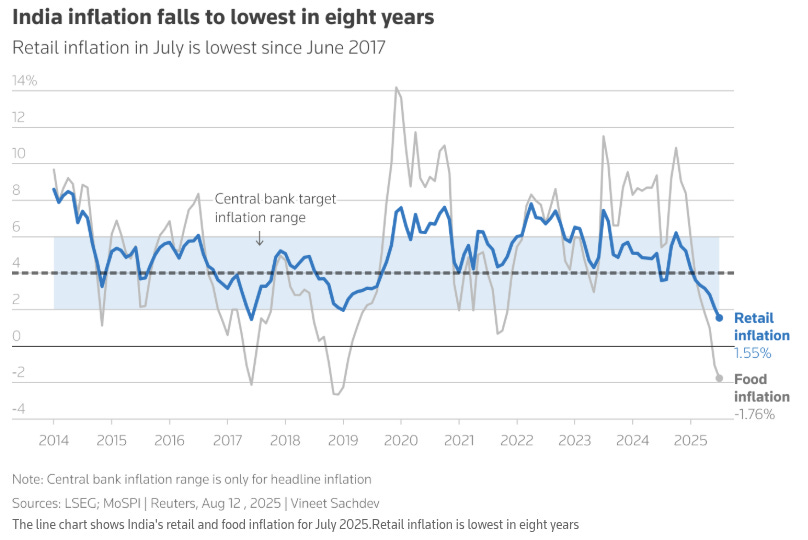

India's retail inflation eased to 1.55% in July 2025, the lowest in eight years, driven by falling food prices like vegetables and pulses. While this offers relief to consumers, it may limit the Reserve Bank of India's room for further rate cuts.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Manie

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Great write..I love it🤗

The difference between American industries and Indian industries is that America knows how to capture “sentiment” value of money. If the fundamentals are good the valuation generates returns which are mind boggling. If fundamentals are not good, they flash hard and then die quickly too.

India on the other hand is extremely fundamental driven but lacks grand visions about future.

Understood it is “dangerous“ and “immature”, but visionary people are always misunderstood initially.

When Elon says he wants to send people to mars, people still joke that he is crazy. But irrespective the guy got a grand vision. Now that’s the fuel for sentiment or the perceived value of money (also commonly called as “valuations”)

Somehow seeing generational poverty means Indian firms still don’t dare to dream big. Until then the sentiments will always be self-critical. I hope this changes in the future.