How India Controls the World’s Rice Supply

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s back to feeding the world!

Is self-employment in India a choice — or a last resort?

India’s back to feeding the world!

The prices of rice across the world are falling dramatically. The price of a metric tonne of benchmark Thai white rice plunged to $405 last week, compared with $669 in January 2024. And behind this story is India. Our country, make no mistake, is a behemoth in the global cultivation of rice. We are the world’s largest rice exporter, accounting for roughly 40% of global rice exports. And our domestic policies shape what people across the world pay for their daily meals.

See, in the last couple of years, India placed a lot of restrictions on different types of rice exports. We started lifting those restrictions recently. And that caused rice prices to tumble everywhere. Rice cultivation is one of the few economic segments where we’re actually dominant. When India’s rice market “sneezes,” the rest of the global rice market catches a cold. Now that we’re resuming full-scale rice shipments, world supply has jumped, and prices are sliding back down.

This latest cycle in rice prices started way back in 2022. Let’s rewind to what was going on just before this.

Let’s talk about rice market (and India’s starring role)

Rice is one of the most widely eaten cereals across the world. In South and Southeast Asia — Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Thailand — as well as parts of Africa, rice can account for up to two-thirds of people’s daily calorie intake.

Historically, though, India wasn’t a rice-export giant. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, our rice production was too low to feed our own population, so India was a net importer of rice. But then, the green revolution struck. By the early 2000s, thanks to better yields and higher production, we started building an export presence. Fast-forward, and in the last 10–15 years, India has become the world’s largest exporter of rice. We accounted for about 40% of all rice exports in 2022-23.

With this level of dominance, though, India can move global rice markets. Whenever India changes its rice trade policy — say, imposing or lifting an export ban — global prices shift. That’s precisely what happened a couple of years ago.

What happened in 2022?

Throughout much of 2022, the prices for big crops like wheat and maize had sky-rocketed. After all, Russia and Ukraine are both agricultural powerhouses, and when international trade from that part of the world took a beating, it caused food shortages across the world. In fact, this was the largest increase in world food insecurity because of military actions in almost a hundred years.

Neither country grew a significant quantity of rice, however. And so, rice markets stayed relatively calm for a while. But that would soon change. Towards the end of 2022, rice prices started creeping upward — partly because Pakistan experienced its worst floods in over a century that year, and partly because everyone was afraid that El Niño patterns would lead to droughts in parts of Asia in 2023, slashing rice harvests.

This is when India’s government grew concerned that domestic rice prices would spiral out of control. And so, it stepped in to intervene. The government started placing export controls on a variety of rice exports in September 2022: ranging from high export duties to a complete ban on broken rice exports.

About a year later, with inflation still rising and a general election looming in spring 2024, India tightened those restrictions further—extending them to non-basmati white rice and putting a 20% duty on parboiled rice.

So, in short, the government’s logic was: “If we limit how much rice can leave the country, we can keep more rice at home and hopefully keep a lid on prices.” But did it work that way? What impact did these restrictions have domestically and internationally?

First, Domestic Effects

You might assume that blocking exports would at least make domestic prices fall — more supply stays at home, after all, so prices go down, right? In theory, yes. In practice, India’s retail rice prices kept climbing throughout 2023, only flattening out in early 2024.

They began to dip in June 2024, but they still hover around 10% above what they were before the restrictions.

Why is this the case? A possible reason is that the price you see on store shelves isn’t just “the cost of growing rice.” It’s heavily influenced by milling, transportation, energy, and labor. With overall inflation rising, it’s possible that these factors affected rice prices as well. We aren’t sure, however.

This makes the impact of the trade restrictions on Indian consumers difficult to assess. While the steps were taken with good intentions of controlling inflation, that did not work out as well as the government had hoped. Would prices go up further if there were no export restrictions? Or would that make a minimal impact? We honestly can’t give you a good answer.

At the same time, it’s also important to consider who bore the brunt of these measures. See, fundamentally, farmers either sell paddy to government procurement agents, through APMC (Agricultural Produce Market Committee) mandis, which serve as regulated marketplace hubs, or directly to private markets. Government agents buy paddy at a pre-determined Minimum Support Price, which is largely immune to market forces. Farmers also have limited pricing power when they sell their produce through APMCs — especially where agents are involved. Ultimately, regular market forces only play out outside this ecosystem.

When the export ban kicked in, overseas markets were suddenly off the table. A large part of the private market dried up. Farmers and millers who depended on the premium prices they could earn abroad reportedly faced lower domestic prices for their paddy or processed rice — losing out on higher international margins (do note, though, that we couldn’t really find comprehensive data on this). For exporters, too, business dried up overnight. Some pivoted to the domestic market, but not all could offset those lost revenues.

Next, Global Effects

On the world stage, rice prices responded quickly once India tightened its export curbs. From July 2023 to late September 2024—when the restrictions were toughest—the widely watched Thai white rice price averaged $615 per metric ton, up about 20% from pre-ban levels .

Many countries in West Africa and South Asia that rely heavily on India’s rice saw local prices climb sharply. After all, several of them got more than 50% of their imported rice from India — a source that was suddenly closed.

Eventually, the market began balancing itself. Other exporters like Pakistan jumped in to supply some of India’s former customers, even hitting record exports. For a while, they could command premium prices. As soon as India re-joined the market, however, many buyers flocked back to cheaper Indian rice, causing Pakistani prices to tumble.

Now where are we?

Here we are in 2025. India has just lifted its final restrictions, and the price of Thai white rice is down to $405 a metric ton, from $669 in January 2024 . That’s a dramatic drop, and it’s partly because India’s low-cost rice is back in the market. Poorer countries that rely on imports are breathing a sigh of relief.

In the meanwhile, it’s clear that our domestic rice policy is both powerful, and under-powered:

On one hand, India’s export controls created ripples across world markets. Rice prices rose by about 20%, and importers scrambled for alternative suppliers.

On the other hand, we didn’t really meet our policy objectives. Domestic retail prices didn’t necessarily fall as much as one hoped. At the same time, rice farmers and exporters in India had to suffer lost incomes when they couldn’t sell abroad.

Ultimately, our policy toolkit in these matters is constrained by the complexity of our agricultural ecosystem. As we’ve mentioned previously, in the context of fertilisers, Indian agriculture is full of economic imbalances — because of a complex labyrinth of policy choices we made in the License-Raj era. These are a constant source of headaches. If we can’t solve those underlying issues, we are bound to see many of our policy levers fail.

Is self-employment in India a choice — or a last resort?

There’s a peculiar challenge in how we measure India's job market.

See, India’s official data on employment comes from something called the ‘Periodic Labour Force Survey’ or ‘PLFS,’ that is conducted by the National Statistical Office. While there are other reputed sources too — such as the CMIE’s unemployment surveys — in many quarters, this is essentially the ‘gold standard’ for understanding who has jobs and who doesn't in our country. But like with any statistical exercise, the PLFS too is built on top of many assumptions. And once you start questioning those assumptions, you realise that there are layers of nuance behind India’s headline employment data.

Consider this, for example: the PLFS counts someone as "employed" if they worked for even one hour during the reference week of the survey. One hour. That's an extremely low bar. Imagine a person who did odd jobs for just 2-3 hours in a whole week being classified the same way as someone with a stable 40 or 50-hour job. Both would appear similarly in the statistics, though their economic realities differ considerably.

Because of how the PLFS measures things, it doesn't really distinguish between different qualities of employment. To the survey, someone with a secure job with benefits, a temporary position that pays daily wages, and someone barely managing through occasional odd jobs — all fall under the same "employed" category. So when we cite official employment statistics, we’re essentially clubbing together vastly different realities under one deceptively simple number.

One of the most interesting categories of ‘employment’ under this survey are those that are ‘self employed’. These are all people that, in theory, have ‘work’. When you first come across this term, you might picture people who run thriving businesses. But we recently came across some fascinating data from our good friends at Data for India, that forced us to dig into this question: who, actually, are India’s self-employed workers?

Here’s everything we found.

What does self-employment mean, really?

According to official statistics, by and large, a majority of India’s workforce is self-employed. Around 60% of our workforce falls into this category. But what exactly does self-employment mean in the Indian context?

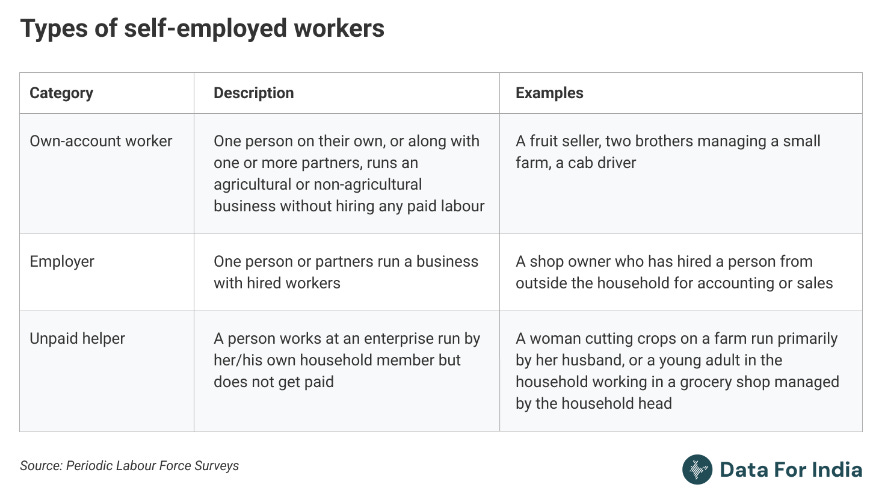

As you’ve probably guessed by now, this isn’t just a collection of all the successful entrepreneurs running thriving businesses in our country. Instead, it covers three very different types of people:

Own-account workers (who run tiny operations without hiring anyone)

Unpaid family helpers (who work in family businesses without wages)

A small number of actual employers who hire others.

It’s the third of these categories that corresponds the most closely to our idea of an ‘entrepreneur’. These are the ‘self-employed’ workers who are actually job creators — whose self-employment puts them in a distinctly better position that the average salaried worker. But how many ‘self employed’ people are actually in that category? Here's a crucial insight from Data for India: out of all these self-employed people, only ~6% actually hire other workers.

When you exclude that small sliver of workers, you’re left with a mass of other self-employed workers. These people — 94% of self-employed workers — are engaged in a wide range of activities, either working alone or helping family members without any significant pay.

In a best case scenario, these might be well-paid workers, such as freelancers or consultants. Much more frequently, however, these are street vendors, domestic servants, taxi drivers, plumbers, delivery riders, or others that run marginal operations to support themselves. All of these would be considered “own account” workers.

Beyond that, though, these could be people that help out in their family business, without receiving a wage in their own name. Let me give you a more concrete example of how this plays out in real life.

Consider a small farm owned by a family. Chances are, the entire family helps out at the farm, and the entire family lives off whatever they earn by selling their produce. There’s no real distinction in what different members of the family earn.

Now, here’s where things get complicated. That land might actually require two people to cultivate effectively — but in reality, five family members could help out with odd tasks around the farm, for lack of anything better to do. All five are counted as "self-employed in agriculture" in our statistics, but three of those people are essentially redundant. Their marginal productivity is close to zero. They're only working on the family farm only because there's nowhere else for them to go.

Economists call this "disguised unemployment." That’s when people appear employed on paper but contribute negligible productivity. Our employment statistics alone miss this nuance.

The same dynamic often plays out in countless small family businesses across India. A tiny shop that would ideally be managed by one person might have three family members involved. All would be counted as self-employed, despite the fact that three people are essentially sharing work that one could handle. This isn't entrepreneurship; it's simply like the distribution of limited work among multiple people who possibly lack meaningful alternatives.

All of this raises a fundamental question: is self-employment in India truly a choice, or is it more of a fallback option when regular jobs aren't available? One of India’s biggest challenges in trying to understand our employment scenario lies in the fact that we cannot accurately answer this question. We can only count the number of people that are working somewhere; there’s essentially no realistic way of understanding how many people actually should be working there.

Self-employed workers: what does the data tell us?

While we don’t have direct data to really understand this category, though, there’s a lot of insight to be found in the data that we do have.

What do self-employed workers earn?

For instance, when you dig into the income figures, this reality becomes much more stark. The average monthly income for a self-employed person in India is around ₹13,200. Compare that to what salaried workers make — about ₹20,700 per month on average. In essence, India’s ‘self-employed’ workers earn ₹7,000 less every month than their salaried counterparts. Put differently, salaried workers see more than 50% higher earnings for those with regular employment.

Clearly, a vast majority of self-employed workers are worse off than those with regular jobs.

Moreover, that figure of ₹13,200 too hides a lot of variation. Evidently, the small slice of self-employed who are also job creators — 6% of them, that is — earn substantially more than own-account workers and unpaid helpers. The remaining self-employed workers most probably earn even less than that.

Regional disparities in self-employment

Regional data supports this interpretation as well. If self-employment were a proxy for entrepreneurship, you would expect India’s richest states to have a lot more self-employed workers. The reality, though, is the exact opposite.

Self-employment is much more common in India’s least industrialized states — like Uttar Pradesh, where nearly three-quarters of workers are self-employed. Most BIMARU states are in a similar situation. In contrast, the situation is different in most of Southern India, where 50% or less of the workforce is self-employed. In an industrialized state like Tamil Nadu, for instance, only one in three workers is self-employed, with many more in salaried roles. If self-employment were primarily driven by entrepreneurial spirit rather than necessity, we probably wouldn't see such a strong correlation with lack of industrial development.

Self-employment and gender

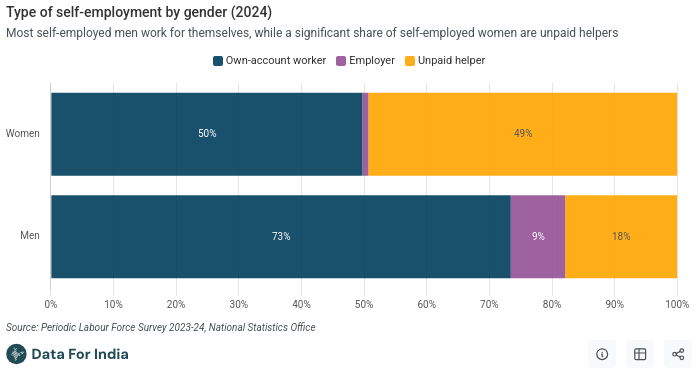

There's a significant gender dimension to ‘self-employed’ Indian workers.

About half of all self-employed women are unpaid helpers, essentially working in family businesses without earning their own income. They contribute labour to household enterprises — maybe a small shop, or agricultural work — but don't receive wages and have limited financial independence. In contrast, three out of four self-employed men are own-account workers, running their own small operations.

Women are virtually absent from the employer category, which means very few women in self-employment are in a position to hire others and grow a business.

Here’s something interesting, though: a couple of decades ago, a lot more women were unpaid helpers in family businesses. There’s been a notable shift, as an increasing number of women have become own-account workers.

To be clear, this does not imply prosperity, by far. It does, however, point to the possibility that women are more financially independent than they were twenty years ago.

Self-employment across geographies

International comparisons drive this point home even further. India's self-employment rate is exceptionally high by global standards — far exceeding other major emerging markets. For instance, Brazil has about 32% self-employment:

Meanwhile, China officially reports around 21-23%.

India's self-employment levels have remained largely unchanged since the 1980s — hovering around 60% of our workforce despite decades of economic growth. This points to self-employment being a structural issue for our economy, rather than a dynamic response to market conditions. The only countries with similar rates to India tend to be low-income agrarian economies with limited formal job creation.

How India’s self-employed react to economic cycles

Another way to understand India’s self-employed workforce is to look at what happens when economic conditions change.

Take the pandemic, for example. Over the COVID years, formal employment fell while informal self-employment rose. This counter-cyclical pattern — where self-employment increases when the economy is under stress — strongly suggests that for many, self-employment is a last resort rather than a preferred option.

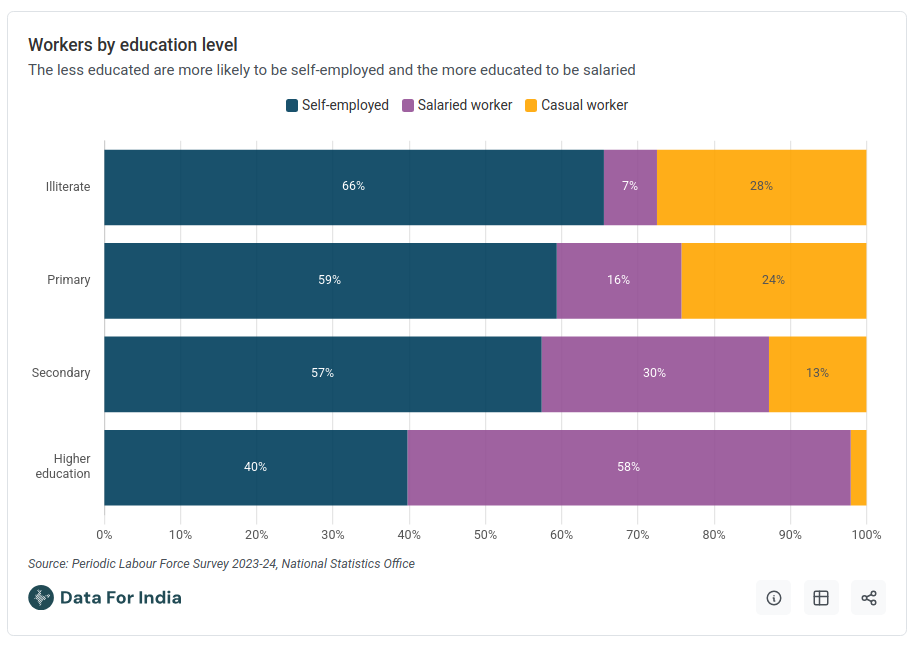

Education and self-employment

Education levels tell a similar story. Workers with higher education levels are far less likely to be self-employed. They seek and often secure salaried jobs, while those with limited education end up self-employed by default.

What self-employment means to Indians

To be clear, there is a segment of India's self-employed who are successful entrepreneurs. Those 6% who employ others, and some portion of the own-account workers, are pursuing business opportunities by choice. They’re driving India’s economic growth. But the evidence suggests they are a minority within the self-employed category. For most, self-employment is a coping mechanism rather than a path to prosperity.

For people who like understanding India’s economy, like you and I, this distinction matters enormously. If our high self-employment rates were a sign of a thriving entrepreneurial culture, our economic policies would revolve around how to support small businesses and startups. Instead, so much of our self-employment is a consequence of structural issues within our economy, which are holding back job creation. To improve things, we should prioritize different interventions - like helping expand formal job creation, investing in manufacturing, and developing skills that make people employable in growing sectors.

There’s another lesson here: improving how we measure and understand employment is essential if we truly want to address the real challenges facing India's workforce. Otherwise, we risk celebrating employment figures that look impressive on paper but fail to reflect the economic reality for millions of Indian workers.

Tidbits

In a key amendment to the Finance Bill, 2025, the government has scrapped the 6% equalisation levy applicable on online advertisement services offered by non-resident digital companies such as Google, Meta, and X. The levy targeted revenues from Indian advertisers paid to foreign platforms without a physical presence in India. This change follows the earlier rollback of the 2% levy on e-commerce transactions, effective August 1, 2024. While the 6% levy has been removed, the corresponding income-tax exemption under Section 10(50) has also been withdrawn, bringing such income under regular tax provisions. The amendment is part of 59 changes made to the Finance Bill 2025 presented in Lok Sabha. The move could simplify compliance for foreign firms while maintaining tax inflows through conventional routes.

Mahindra & Mahindra is in discussions to acquire Sumitomo Corporation’s 43.96% stake in SML Isuzu, valued at approximately ₹1,100 crore based on the company’s current market capitalisation of ₹2,500 crore. Reports suggest M&M is considering a purchase price of ₹1,400–1,500 per share, which would value SML Isuzu at around ₹2,000 crore. SML Isuzu’s commercial vehicle sales remained largely flat in FY25 (April–February), with a marginal 0.2% year-on-year growth. The company saw a 35.8% rise in passenger vehicle (bus) sales and a 15.3% increase in cargo vehicles last month. In the first nine months of FY25, it reported a 7.34% increase in revenue from operations to ₹1,627.61 crore and a 23.69% jump in profit after tax to ₹68.72 crore. M&M currently holds a 23.5% retail market share in the commercial vehicle segment, led primarily by its light commercial vehicle offerings.

The Indian rupee appreciated for the ninth straight session on Monday, closing at ₹85.64 per dollar—its highest level since December 30, 2024—after hitting an intraday high of ₹85.49. The domestic currency has gained 2.19% in March so far, making it the best-performing Asian currency this month, while overall remaining nearly flat in calendar year 2025 with just 0.03% depreciation. In the financial year, however, the rupee has still declined by 2.61%. The appreciation has been driven by persistent dollar selling from foreign banks, strong corporate repatriation, and robust foreign inflows. Supporting this momentum, the RBI’s $10 billion forex swap auction received bids worth $22.28 billion, with a cut-off premium of ₹5.86. The RBI’s net short dollar forward position stood at $77.5 billion in January, up from $67.9 billion in December. Meanwhile, e-RUPI voucher issuance surged in February with Indian Bank generating 507,550 vouchers and SBI creating 126,810, though redemption remained relatively muted.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Anurag

📚Join our book club

We've recently started a book club where we meet each week in Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you'd like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉