Game-Changing Deal in the Skincare Industry

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

HUL Adds Minimalist to Its Portfolio

AI Chip Export Rules Get Tougher

Pre-IPO Market Buzz in India

HUL Adds Minimalist to Its Portfolio

Hindustan Unilever (HUL) recently shared their quarterly results, and along with it, they made a big announcement: they’re acquiring the skincare brand Minimalist in an all-cash deal. HUL will pay ₹2,955 crores for this stake, making it the largest deal involving a direct-to-consumer (D2C) brand in India.

Now, for those who might not be familiar with Minimalist, here’s a quick introduction. Minimalist is a fairly young company that has grown rapidly by selling skincare products, primarily through online platforms. What’s impressive is that they reached ₹100 crore in revenue in just eight months and have been profitable since earning their first crore.

With this deal, HUL, one of India’s biggest FMCG giants, will own about 90.5% of the brand. The remaining 9.5% will be acquired from the founders over the next two years.

So, why is this news such a big deal? To understand, we need to take a closer look at India’s skincare market.

For a long time, skincare in India has been dominated by well-known brands like Ponds and Vaseline, both of which are owned by HUL. These brands have traditionally focused on broad claims, like moisturizing skin or making it fairer. The issue with such products is that consumers often have to adapt their specific skin needs to these generic solutions.

That’s where newer D2C skincare brands like Minimalist come in. These brands focus on creating products for specific skin concerns. For example, Minimalist offers targeted solutions for issues like acne, hyperpigmentation, and uneven skin tone. Instead of offering one-size-fits-all products, they’re addressing specific problems and providing tailored solutions that customers really need.

In simple terms, this shift from generic to problem-specific products is what’s driving the success of brands like Minimalist. And now, with HUL’s backing, we can expect even bigger things from this fast-growing brand.

Now, here’s the thing—when a big company like HUL sees a new brand doing really well, one obvious question comes up: why don’t they just launch their own products instead of buying another company?

The answer to that is pretty interesting.

First, it’s much harder for big, established companies to experiment with new product types compared to young startups. Since HUL’s distribution network is so massive, any misstep or failure could lead to much bigger losses.

Second, young startups tend to attract a specific group of users and followers who may not connect as well with a large, older brand like HUL. So, buying a brand that has already built a loyal base of customers makes a lot of sense. In this case, HUL isn’t just acquiring Minimalist’s products—they’re also gaining its loyal customer base and online following.

By acquiring Minimalist, HUL instantly gets access to its loyal fans, proven product formulas, and reputation for being transparent about ingredients. Plus, HUL’s huge distribution network across physical stores in India means that products that are already popular online can now reach a much bigger audience, including people who prefer to shop offline.

On the flip side, you might wonder why Minimalist decided to sell such a big part of its ownership when it was already profitable.

For Minimalist’s founders, teaming up with HUL offers huge advantages. While Minimalist was doing great on its own, scaling a business to the next level requires a lot of money, stronger supply chains, and more people. HUL brings all of that to the table.

This partnership lets the founders focus on what they do best: creating innovative skincare products and maintaining the brand’s unique identity. Meanwhile, HUL takes care of expanding the brand across India and potentially even globally.

The acquisition amount, ₹2,955 crore, is obviously a big part of the deal. But just as important are the resources and expertise that HUL can provide to help Minimalist grow even further.

This deal also highlights a broader trend in India, where several large FMCG companies have been acquiring successful online-first brands. Over the past few years, we’ve seen similar moves, like Marico buying the men’s grooming brand Beardo, or Good Glamm Group acquiring the premium brand The Moms Co.

The idea is pretty straightforward: instead of building a new brand from scratch, big companies choose to buy an existing one that already understands the digital landscape and has a loyal customer base.

Coming back to HUL, what happens next will be interesting to watch. By bringing Minimalist under its umbrella, HUL can strengthen its position in the “masstige” segment—a mix of mass-market and prestige products.

Overall, this is a significant moment because it shows that large companies are adapting to a new reality. Consumers today want more than just a familiar name on the packaging; they demand products that meet their specific needs. At the same time, smaller brands, even when they’re profitable, can benefit hugely from the support, resources, and wider reach that a giant like HUL can offer.

This could be the start of many more such deals, shaping the next chapter of the D2C industry in India.

AI Chip Export Rules Get Tougher

American politics has been on the top of our minds lately. Biden’s out. Trump’s in. The internet’s been smothered by a mountain of memes and hot takes on US politics. But while people obsess over silly nonsense like Elon Musk’s hand gestures, there’s something far more consequential that they’ve missed: a few days ago, America created an AI License Raj which affects the entire world — India included.

Of course, America’s been trying this sort of thing since late 2022. When this year began, it already had hundreds of pages of regulations that controlled the access other countries had to AI chips. We’ve written about these before. Days before he left office, though, Joe Biden added a few extra hundred pages of AI restrictions. Although they sound harmless — “Framework for Artificial Intelligence Diffusion” — they’re anything but. They go far beyond what came before. They’re calculated to keep the rest of the world, India included, out of the AI race. Let’s dig in.

There are two things that the Biden administration tried to do with the latest executive order:

The first is familiar: controlling AI for national security. Countries like China and Russia could use AI for everything from mass surveillance to cyber warfare, to human rights abuses, and so, America’s keeping them away.

The second is more interesting, though: maintaining America’s economic leadership. The US lost its lead in technologies like batteries and green technology to other nations, and it wants to avoid a repeat.

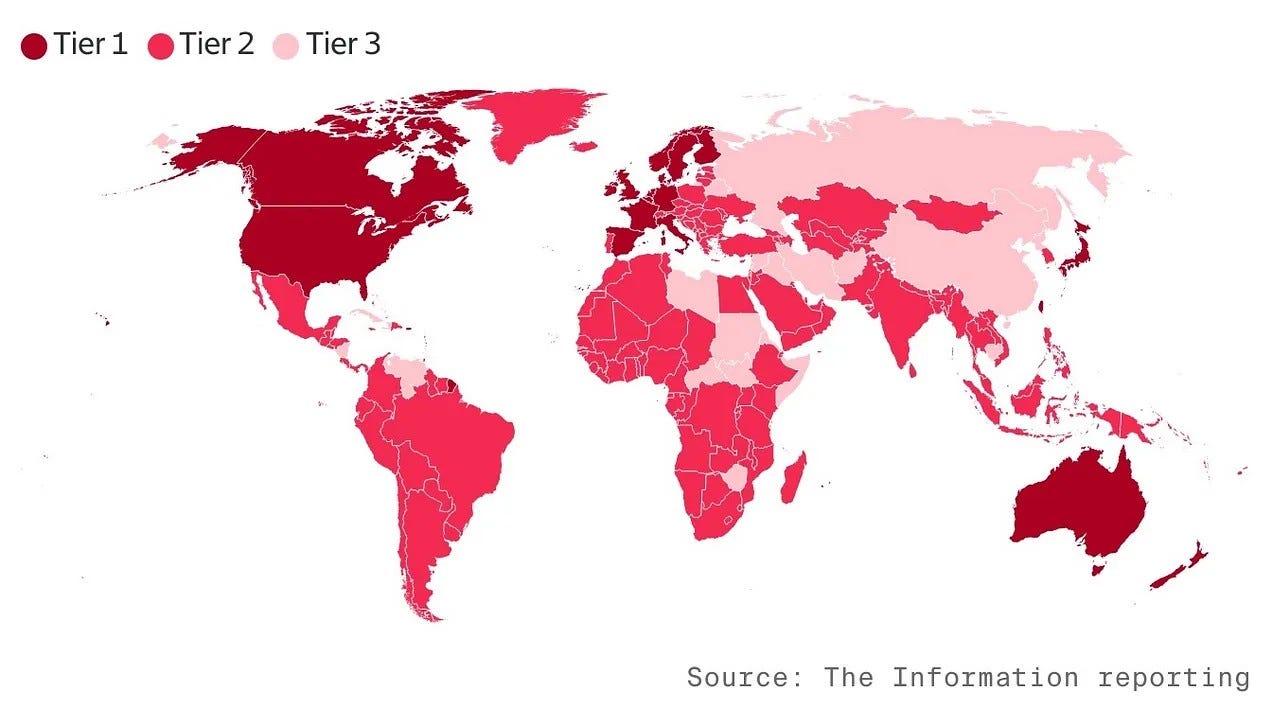

These two considerations show up in how the Diffusion Framework has been designed. It basically splits the world into three camps:

There’s a group of outcasts that America is trying to cut out of its AI ecosystem entirely. These are countries like China, Russia, North Korea, and other big rivals. This group’s already on America’s bad side, though. Many existing controls already target these countries.

Here’s what’s new: the framework creates an inner circle of 18 countries that can basically run their AI industries unmolested. This includes close allies of the US — such as Canada, Australia, or the UK — as well as countries that are important to the AI landscape — like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Everyone else — a group of 120 countries, including India — is given step-brotherly treatment under this new regime. This includes NATO members and US allies, like Poland and Israel. All these nations now face tight quotas and complex compliance requirements.

The first of these groups — America’s rivals — are completely blocked off under the new regime. They don’t get chips, they don’t get access to models, American companies can’t set up facilities in their territories… Basically, if these countries want an AI ecosystem, they can’t count on America’s help. This isn’t a surprise, though. It just scales up restrictions America had already put in place. So far, these measures may have caused headaches for a rival like China, but they haven’t really been a fatal blow.

It’s the third cohort of 120 countries — those that are neither allies nor rivals — that have taken an unexpected hit. This includes India. It’s these countries that now face a License-Permit Raj for their AI ambitions, while no such restrictions apply to America’s inner circle.

What do the measures actually do? America’s essentially trying to control access to two things: advanced chips and advanced models. Its friends get these easily. Everyone else needs to jump through hoops.

Let’s start with chips.

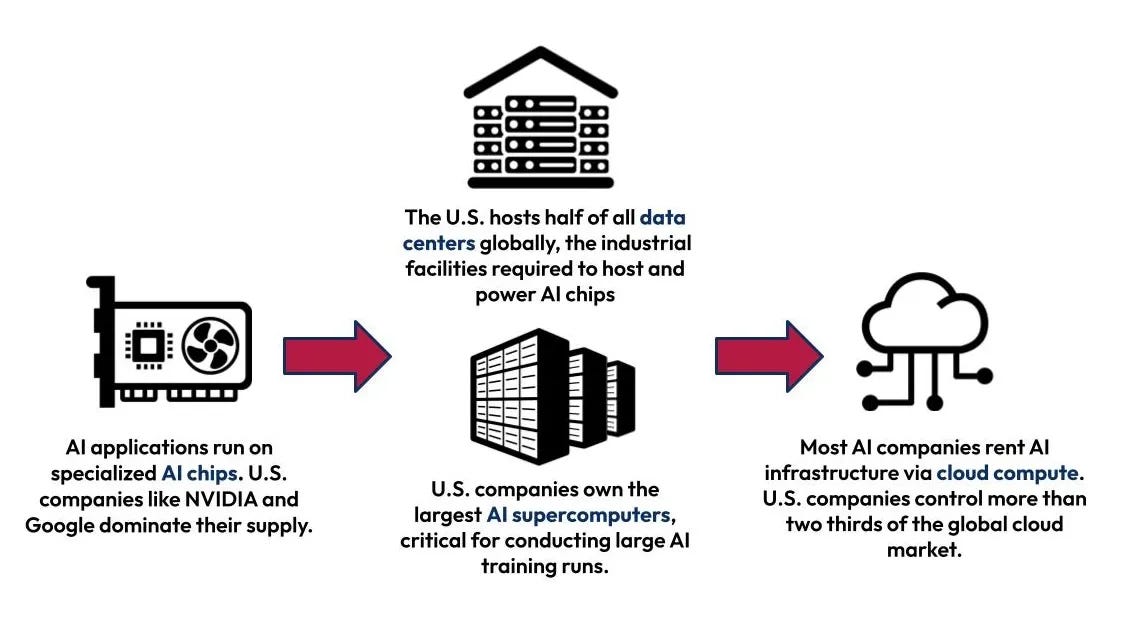

America’s first big bet seems to be that strength in the AI ecosystem will come from control over computing power. It’s easy to see why. At least so far, the entire AI ecosystem depends on it. Today’s AI models are trained by making tens of thousands of advanced chips parse through incredible amounts of data, to find hidden patterns. This is what America wants to monopolize.

Companies from America or its friends can get all the advanced AI chips they want. But if you’re from a country like India, that’s just become a lot more complicated. America has put restrictions on the number of chips you can buy, based on their “Total Processing Performance”, or “TPP”:

Without a license, you’re restricted to importing 26.9 million TPP chips. That’s about the computational power in 1,700 of Nvidia’s state-of-the-art H100 chips. That’s good for small projects, but it’s not nearly enough to build anything at a commercial scale.

For anything beyond that, you need a special license from America’s Bureau of Industry and Safety (or BIS):

Even for that, companies from America and its allies get special preference. If a company like Microsoft or Meta sets up a data centre abroad, it only needs a one-time license, called the “Universal Validated End User License” or ‘U-VEUL’. But this comes with strings attached. At least 3/4ths of your total compute needs to be based in America or its inner circle, and no more than 7% of your compute can sit in any single country outside this inner circle.

Other companies — Indian companies, for instance — get a sub-standard “National Validated End User License” or N-VEUL. For that, you need to give the US BIS a whole lot of data — on what you’re doing, how many chips you need, what protections you have, etc. Once that’s through, you get a fixed quota of chips every quarter, starting at 633 million TPP. Your license will be reviewed with every order you make.

There are a whole lot of other restrictions on top of this — including a country-wise quota for anything above this. America plans to enforce this whole regime by placing stringent requirements on its own chip exporters, who’ll have to take export licenses and report all their chip exports to the government.

All of this is meant to ensure that countries with the money and willpower can’t just amass a whole lot of chips and train their own AI — unless they’re countries the US approves of. An Indian company, for instance, can buy up to 50,000 Nvidia H100 chips a quarter. That’s pretty decent — it’s enough to run a small AI company. But let’s put that in perspective. Most AI work, today, happens in massive data farms run by American hyperscalers like Amazon, Meta, or Microsoft. For perspective, Meta’s Utah data center — just one of its facilities — is the size of 17 Wankhede stadiums, and is filled with chips. If you’re not friends with the US, you’re simply cut out from this game.

But controlling chips is only half the story. The other key piece of the Diffusion Framework is protecting AI model weights.

See, an AI model needs the most computing when it’s initially being trained. It begins this process completely blank. Through training, it creates mathematical relationships that, in a very computeristic sense, are how the model “understands” the world. (If you want to know how this happens, check out this link.) This “understanding” — the contents of an AI brain, so to speak — are called the model’s weights. Once these weights have been figured out, it’s far less expensive to run an AI system.

Now, if you can’t access AI chips to train your own model, can’t you just buy the final model weights from someone else?

That’s another hole that America’s trying to plug. If you’re not in America’s inner circle, you can’t import model weights for advanced AI models — unless you have a license, and comply with all sorts of requirements.

This only applies to models that require 10^26 computer operations for their training. That’s 1, followed by 26 zeroes. How much is that? Here’s one way to think about it:

GPT-3 took around 3 x 10^23 operations to train. The threshold is 300 times GPT-3’s size. You can comfortably import its weights.

But the next model, GPT-4 took 2 x 10^25 operations. That’s just below the threshold. You can import the weights for GPT-4, but it’s really tight.

The next model will probably be many times as big. In essence, therefore, we can import the weights for today’s state-of-the-art models, but the next cutting-edge model will be beyond our reach. Future AI systems will be locked inside the US and its allies.

So. What does all this mean?

In the short term, nothing — at least for us, here in India. At the moment, we don’t have the hyperscalers or AI companies that really want any of these things. But with time, as our businesses grow in scale and ambition, and as the benefits of AI become clearer, these restrictions might pinch us much more. This will probably be the story of most countries.

America currently has a big lead in every step of artificial intelligence. It makes AI chips, runs the data centres that host them and makes the world’s best AI models. Even without these restrictions, the US was already poised to dominate the industry, with China as a distant second.

But the United States also knows that its lead is fragile. Chinese AI models are almost at par with American ones, despite working with inferior hardware. Recent Chinese models, like those released by the company DeepSeek, go toe-to-toe with the best that America has. This could become a problem. To protect its lead, America is trying to consolidate the biggest advantage it has — access to resources. If the Diffusion Framework survives Trump’s scrutiny — and that’s a big ‘if’ — these measures will probably entrench American dominance over the sector.

These restrictions might also increase America’s leverage in its trade war against China more broadly. It’s already using AI to throw its weight around. Last year, for instance, America refused to let the Emirati AI giant, G42, import Nvidia chips — until the company pulled out of China, replaced its Huawei technology, and partnered with Microsoft. This new regime will simply formalize this arm-twisting.

But if there’s one thing India can teach America, it’s that a License Raj rarely goes to plan. The Diffusion Framework creates a lot of government paperwork and a massive regulatory burden. The department meant to enforce it — the BIS — is understaffed and under-resourced. Companies hate the regime. In a recent statement, Nvidia described this measure as being “misguided” and said that it could “derail innovation and economic growth worldwide.” Oracle described this as “by far history’s worst government technology idea”. Many countries, too, are angry at being cut out from America’s inner circle. The harms of these restrictions may eventually come to outweigh their benefits.

But chances are that this won’t matter. The stakes are too high. America sees China coming for its number one spot, and it’s willing to fight. This isn’t really a commercial tussle — it’s a technological arms race.

But there’s a cruel irony here. America championed free trade for half a century. Twenty years ago, it had ambitions of turning China into a free market champion as well. That’s why it brought China into the WTO fold. But if anything, it’s America that has become more like China. To protect its own position in the world, America has suddenly embraced a China-like policy. Funny, isn’t it? As they say, you become what you hate.

Pre-IPO Market Buzz in India

Soon, India may have an official version of the pre-IPO market.

At an event hosted by the Association of Investment Bankers in India (AIBI), SEBI Chairperson Madhabi Puri Buch announced that SEBI is working with stock exchanges to formalize this market. Currently, once the bid window for an IPO closes, a company is required to list on the exchanges within three working days. For example, if an IPO closes on a Monday, the company will list on Thursday. This leaves only Tuesday and Wednesday for a potential pre-IPO market.

This raises an important question: Who can participate? If participation is limited to investors who know they will receive an allotment, the challenge arises because, in this example, allotments are only finalized on Tuesday night. That leaves just one day - Wednesday, for pre-IPO trading. Might as well wait for Thursday.

Alternatively, anyone can be allowed to participate without the need for an allotment. This causes problems, too. Pre-IPO trading could become a speculative market where trades are entered without the requirement to settle the transaction until the stock is officially listed. This allows the pre-IPO market to be open for a longer period. But it would be like allowing F&O trading for stocks even before they list their equity instrument.

For now, here’s all we know for sure: something is in the works. SEBI and stock exchanges are determining how this market will function. Though significant, the announcement was brief and left several questions unanswered. Some media reports have speculated about the framework, but clarity will only emerge once SEBI provides more details.

In the meantime, the unofficial grey market for IPOs continues to operate over a much longer period, typically from the start of a roadshow until the listing date. These trades are more akin to bets, settled outside official channels. Stock market punters might still favour the familiar grey market over the restricted open market.

Tidbits

JSW Group has announced an investment of ₹3 lakh crore in Maharashtra. Their plan covers several areas, including steel production, renewable energy, electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries, and solar modules. The state government has promised faster approvals and tax incentives to support these initiatives, which are expected to create thousands of jobs and boost Maharashtra’s overall economic growth.

Gold prices have climbed to their highest level in eleven weeks. Spot gold has risen to $2,751.89 per ounce, with U.S. gold futures touching $2,768.40 per ounce. These prices are now close to the October peak of $2,790.15 per ounce. The surge is linked to growing uncertainty in global markets, fueled by U.S. President Donald Trump’s proposed tariffs on European goods and a separate 10% tariff on Chinese imports scheduled to start from February 1.

Essar Renewables is also stepping in with a significant commitment of ₹8,000 crore to develop 2 GW of renewable energy in Maharashtra. Their focus will include green mobility projects, with plans to support electric vehicle truck charging for Blue Energy Motors. Work on these projects is set to begin in the 2026–27 financial year and is expected to create over 2,000 direct jobs in the region.

-This edition of the newsletter was written by Anurag, Pranav and Mohit

🌱One thing we learned today

Every day, each team member shares something they've learned, not limited to finance. It's our way of trying to be a little less dumb every day. Check it out here

This website won't have a newsletter. However, if you want to be notified about new posts, you can subscribe to the site's RSS feed and read it on apps like Feedly. Even the Substack app supports external RSS feeds and you can read One Thing We Learned Today along with all your other newsletters.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

Crisp and quite important stuff!

AI topic is interesting. Kudos!!! 👏