Hi folks, welcome to another episode of Who Said What? I’m your host, Krishna. For those of you who are new here, let me quickly set the context for what this show is about.

The idea is that we will pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualize things around them. Now, some of these names might not be familiar, but trust me, they’re influential people, and what they say matters a lot because of their experience and background.

So I’ll make sure to bring a mix—some names you’ll know, some you’ll discover—and hopefully, it’ll give you a wide and useful perspective.

With that out of the way, let me get started.

Is this the end of Dream11?

Let’s say you started a business years ago. You fought through the early doubts, convinced people to give you a chance, and slowly built a base of millions of loyal users. Some loved what you were doing, some hated it. But the numbers spoke for themselves, people kept coming back, and the money kept flowing in. Then one morning, you wake up to find the government has told you to stop. Not pause, not tweak, not regulate, but stop. Overnight, everything you built is gone.

That’s the situation India’s online real-money gaming companies are in today. And at the very center of it sits Dream11.

“95% of our group's revenues have disappeared overnight and 100% of our profits. So the only way we believe to come out of this is by building by rebuilding… we will not be having any layoffs. We will be investing in our people to dig us out of this hole.”

The government’s decision came fast, almost abrupt. Within days, Parliament pushed through a blanket ban on all online games involving money. Harsh Jain, Dream11’s co-founder, went on CNBC-TV18 to say that while he believed regulation was the way forward, he wasn’t going to fight this in court.

“Dream 11 will not be challenging this law. If the law changes at any point… we can explore those business opportunities then. But no, this is not some place that we want to fight.”

The ripple effects of this are massive. An article from Ken, a business news publication, saus that aggregators such as Cashfree and Razorpay had built thriving businesses on gaming flows. Online games accounted for about 350 million UPI transactions. In 2024, Indians spent somewhere between ₹50,000–60,000 crore on real-money games — a figure that was expected to double this year. All of that volume and margin just vanished.

Advertising too has been gutted. Dream11 reportedly spent around ₹1,000 crore a year, with the broader industry spending nearly ₹10,000 crore. That money went into cricket leagues, into influencer campaigns, into sports teams that are now scrambling for new sponsors.

The government, though, has been determined. IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw defended the move, calling online money games a “social menace bigger than drugs”. He said students were falling into debt, even resorting to crime, and that families were being devastated. His argument was simple: better to take the pain now than let this spiral further out of control.

But the critics have a different worry: prohibition rarely kills demand, it just pushes it underground. As Bloomberg columnist Andy Mukherjee put it:

“...all that prohibition ever does is push users toward moonshine — in this case offshore casinos. They will take in wagers and pay out winnings via crypto, giving a boost to illegal, two-way money flows.”

In other words, the government may have only moved the problem into darker corners, where regulation and consumer protection don’t exist.

And yet, even Harsh Jain’s defense has a strange irony to it. He pointed out to Moneycontrol that “99% of Dream11’s 260 million users never won or lost more than ₹10,000 in their lifetime.” The average ticket size was just ₹51. For many, it wasn’t a livelihood or an addiction — it was the popcorn to their cricket movie.

Still, the law is the law. Some like Dream11 have accepted it. Others, like A23’s parent Head Digital Works, have gone to court, arguing that the ban is unconstitutional and violates the right to livelihood. The Karnataka High Court will hear that challenge soon.

For now, one of India’s fastest-growing industries, valued at billions, employing thousands, and touching everything from fintech to cricket sponsorships, has been shut with the stroke of a pen. Whether that ends the menace, or just shifts it offshore, is the question that will define what comes next.

The art of the (Intel) deal

Longtime viewers of this show may already know that US President Donald Trump is a regular feature on our show. And we have a whole story to tell through his social media posts.

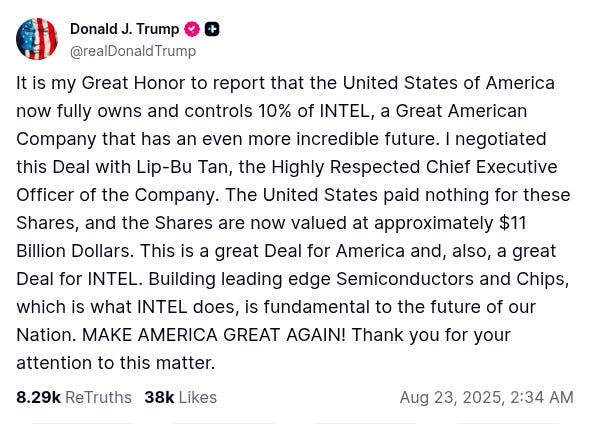

What did he do this time? Well, under his leadership, the US government bought 10% of legacy chipmaker Intel (whose fall we covered on The Daily Brief). And this stake, he boasts, was bought for free.

Now, the problems with Intel — once the world’s best chipmaker — are well-known. They’ve fallen behind key technologies that their competitors (many of them non-American) have taken up — including AI. They’ve had multiple changes in leadership that failed to turn the company around.

The US government has been unhappy that they have lost market share to outsiders. In an attempt to boost domestic chip-making, they promised Intel with $9 billion worth of subsidies (under the CHIPS Act). In fact, they were in talks since January with Intel’s board to discuss acquiring a stake. But the board didn’t like the terms of the deal.

So, what changed? Turns out, there is a lot of backroom drama behind this deal (unearthed by Wall Street Journal). And all of it unfolded in the last 3 weeks.

The story starts with Intel’s new CEO, Lip-Bu Tan. Tan was known as a pioneer in Asian venture capital. He made money by investing in many early-stage startups across Asia that most others didn’t believe in. He also served as the CEO of another American chip company called Cadence Design. He definitely didn’t lack the qualifications for the top job at Intel.

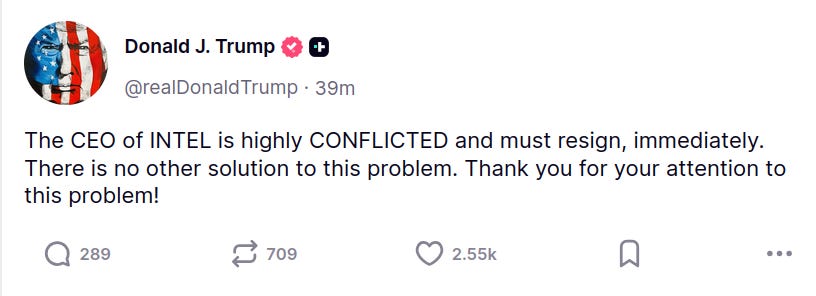

However, some of Tan’s startups were strongly tied to the Chinese military. Cadence was also accused of exporting key chip designs to the Chinese military. This made Tan the target of an investigation by America. Trump was furious, and demanded that Tan resign earlier this month. A rare case of the state ordering a private company CEO to step down.

Some say that this wasn’t merely an order — it was an opening bid that bargained low for Intel. And the effect was instant: Intel’s already-falling stock plummeted further the day after Trump’s post.

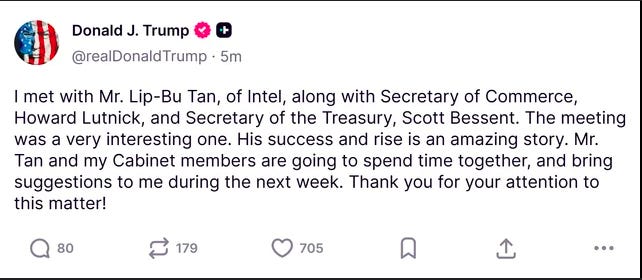

So, the Intel board moved swiftly, asking for a meeting with Trump the very next day. Tan made the most of the meeting — not only did he convince Trump he was not a Chinese spy, he also convinced him why the US government should help Intel. And Trump was impressed.

A truce seemed to be close and Tan’s job looked to be saved, but there was a cost attached to it. The US government now proposed to convert the subsidies promised to Intel into a 10% equity stake in the chipmaker — that too at a discounted valuation. This was an unusual deal — government grants don’t usually get turned into equity stakes. Here’s what Trump said:

“He came in, he saw me, we talked for a while. I liked him a lot, I thought he was very good. I said, ‘You know what? I think the United States should be given 10% of Intel.’ And he said, ‘I would consider that.’”

This deal came in with even more restrictions. The US government strongly insisted on a special provision which was eventually added — they could take an extra 5% stake at a discount, if Intel decided to sell its manufacturing business. This is meant to dissuade Intel from doing exactly that.

Around the same time, Intel got another (private) source of funds: SoftBank, who bought a stake in the business for $2 billion. But this is no isolated deal. SoftBank founder Masayoshi Son has been deepening his friendship with Trump—even promising a $100 billion infusion into American AI and chip industries right after his presidential inauguration. The timing of SoftBank’s Intel deal is probably not a coincidence — Trump’s moves were the signal.

And this story goes beyond Intel. The word is that Trump is looking to make more such deals, all in the name of securing America’s technological superiority. The Intel deal is hardly the first of its kind — in July, the Defense Department secured a minority stake in a maker of rare-earth magnets.

But will this strategy really work? Intel’s problems really boil down to how they’re organized (or not) around new technology, and a change in ownership will definitely not save that. More so if the Trump administration is involved, as they could pressure Intel’s existing shareholders in perverse ways to achieve their goals.

More importantly, though, this is bad news for competition. The US government is prioritizing saving big firms rather than fostering new, younger players who could move faster. If Intel dies despite all of this, that $9 billion would be wasted.

One thing is clear: under Trump’s thumb, the US tech industry is living in a very unpredictable world.

L&T and the economy

S.N. Subrahmanyan runs Larsen & Toubro. That is, many of India’s investment plans, once they’re sanctioned, land up on his desk. And that, in our view, is an incredible vantage point to have. While he’s the spokesperson of his own company, he also has ring-side seats to the entire economy.

He recently gave an interview to CNBC-TV18’s Latha Venkatesh, and we’re digging through it to try and understand where India is in its investment cycle. Here’s what we gathered.

The first thing that caught our eye were his inputs on demand. After all, we seemed to have entered a period of war and trade troubles. Consumption is down; it feels like the economy is holding back on spending. Does this also mean a slowdown in capex?

Not if he is to be believed. If anything, he has an order backlog to deal with:

“Our order book today — the backlog of orders to be executed — is more than 6,25,000-6,30,000 odd crores. Which means, from an EPC point of view we have more than 2 and a half years of work as we look forward, and these are fairly fast-track orders, in the sense that many of them have to be done in 2-and-a-half to 3 years. So, as an organization, today we seem to be on a firm footing”

Those orders are coming in from everywhere. It’s not just government projects the company is seeing, but projects of every variety:

“You have central government projects; you have multilateral-funded projects; and you have a fairly healthy private order in-flow… these orders are from cement companies, from steel companies, from electronics and fab companies, power…”

The company, in fact, has enough orders flowing in that it can afford to be choosy about what orders it takes up. As Subrahmanyan says:

“Since you have a good backlog, any order that comes; any client that we come across; any geography that we look at — we tend to analyze it a lot more. The risk perception within the company is better. We tend to negotiate for better terms and conditions. We tend to get better orders. There's no panic situation in the company to desperately go achieve something.”

The company isn’t desperate. It doesn’t have to “win at any cost” — and that could help it avoid mistakes. That is a commanding position to be in, at least for now.

But that order book doesn’t have to translate into revenue. Projects slip; plans change. The biggest challenge for the company, right now, doesn’t lie in sourcing orders, but in executing them. At the end of the day, execution is what turns an order into cash. That, however, is one place where L&T does see challenges. Logistical and geopolitical issues have made things difficult for the company in the recent past. As he says:

“Many of the projects that we do have components or subsystems coming from many parts of the world. There are two broad matters going on in the world. One, there are certain organizations which make some of these critical components which are extremely busy. For example, gas insulated substations, compressors, transformers — they’re overflowing with orders. There are others who don’t have so many orders, but at the same time have logistical issues — not only the Red Sea–Suez Canal matter, but also that many of the components that they do come from many other countries, and these are not reaching them in time.”

L&T’s suppliers, in short, have both a capacity problem and a logistics problem. This is a business where you could have a lot of work, but you could get stranded while waiting for components, while you keep bleeding out cash.

That’s why you simply cannot count your chickens before they hatch. It’s also why margins are always tight:

“On a good day, on a net profit basis, we maybe find out 6% — then we open the champagne. But most of the days, it is at 4-5%, so we get to drink water.”

Lovely framing! Here’s hoping we all have more champagne-moments than water ones.

If you’ve made it this far, please let me know if you have any feedback for me 🙂

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

India is incredibly strict on "unwanted sources of money-making"—activities it deems as vices.

I appreciate this approach, though I also recognize that India urgently needs capitalism with more young millionaires to foster a strong VC-startup ecosystem. This would channel money toward hardworking, ambitious individuals, helping the country grow into a larger economy with more home-grown tech innovations.

What draws me to these regulations is my realization, after eight years on Wall Street, that America loses its ethos once a company reaches a billion-dollar revenue share. Profit becomes the sole guiding principle, which is unhealthy for society in the long term.

Money should always be driven by a higher ideal. Pursuing wealth for its own sake may seem glamorous, but it can also be destructive.

India, however, still values good character over wealth, which makes it a fascinating country in my opinion.

Is this the first time that a Government has converted subsidies into equity ownership? Quite a curious case & Trump doesn’t fail to entertain 👻