From a YouTube channel for physics to a hot IPO

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

PhysicsWallah: From YouTube Channel to 3800 CR IPO

Cash rules everything around companies

PhysicsWallah: From YouTube Channel to 3800 CR IPO

In India, the path to success often runs through a very narrow educational pipeline. A handful of elite institutions — think IITs, IIMs, AIIMS — hold out the promise of upward mobility. But with millions of aspirants chasing only a few thousand seats, the competition is cut-throat.

That’s where PhysicsWallah (PW) has built its business. What began as a scrappy YouTube channel is now an edtech unicorn, and it’s getting ready for a ₹3,820 crore IPO after filing its updated draft red herring prospectus (UDRHP) with SEBI.

We dug into the filing — not just to understand PW’s own journey, but also to get a glimpse of how India’s education market looks when viewed through an investor’s lens.

So, let’s get into it!

The Big Picture

When we zoom out and look at education from a macro lens, it helps to break things down structurally. After all, education isn’t a one-time event — it’s a service we interact with at different touchpoints across our lives.

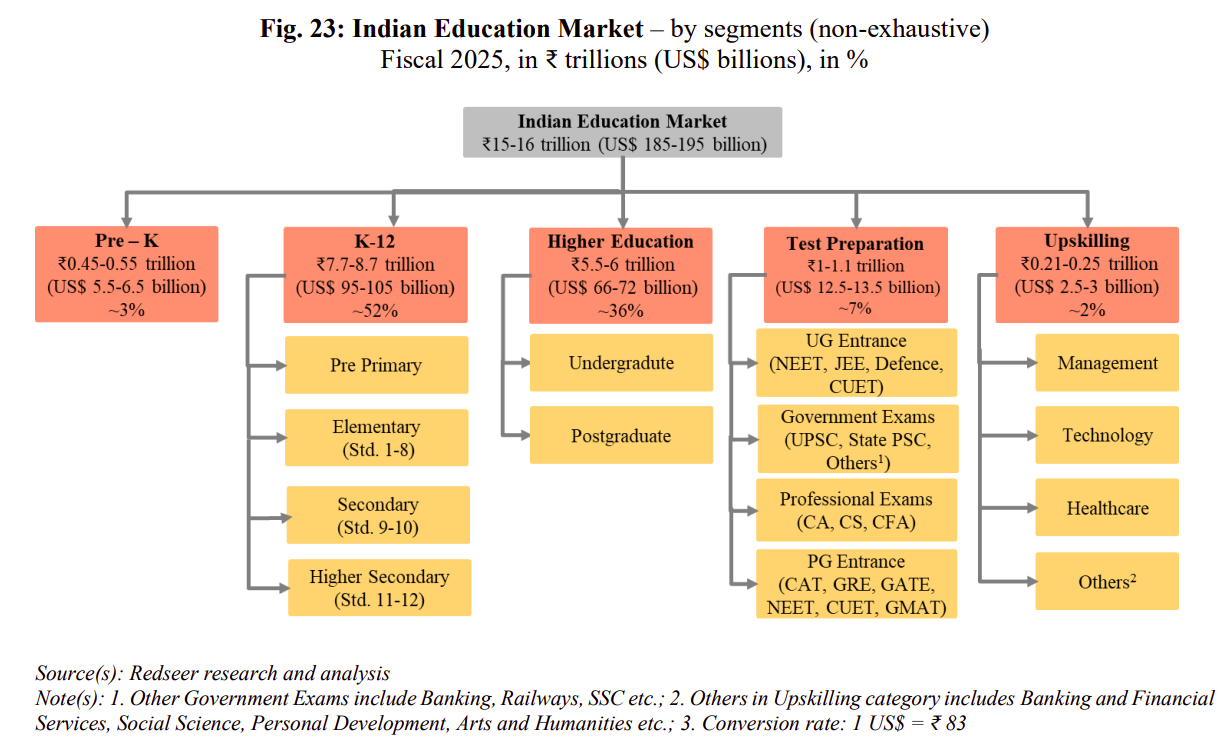

Think about it: it begins with pre-K, the preschool programs that introduce toddlers to learning. Then comes K–12, the schooling years from kindergarten to class 12. This is the biggest slice of India’s education pie, making up more than half of the ₹15 lakh crore market. And it makes sense — as of 2024, India has nearly 37 crore school-going children.

Next is higher education, dominated by colleges and universities that offer undergraduate and postgraduate programs. These are the institutions formally affiliated with government regulators and accreditation bodies — the official backbone of India’s education system.

Then comes test preparation, which isn’t technically part of this regulated system. Instead, it’s a parallel industry that exists to help students crack the very competitive exams that unlock entry into the best courses or the most coveted government jobs. This is where PW has made its name.

And finally, there’s the fast-growing segment of upskilling. With industries demanding job-ready skills, this space is becoming increasingly important for working professionals who need to stay relevant.

Across all these segments, one theme runs deep: fragmentation. India’s education market is still dominated by standalone, unaffiliated institutions with very limited franchise networks.

Contrast that with the US, where the system is far more consolidated. Public schools alone account for nearly 76% of the K–12 sector (as of FY20). A consolidated system usually drives efficiency and scale. Whether it actually leads to better outcomes for society is a whole different debate.

Back home, though, India’s education market is slowly but surely witnessing consolidation — and nowhere is this clearer than in the test-prep industry. For decades, coaching was the domain of small, local centres. Now, national players like PhysicsWallah are snapping up regional brands, standardising delivery, and scaling offline networks.

And that has been the investment thesis for most of India’s edtech startups — including PW. They’re betting that bringing structure and scale to this fragmented system, starting with test prep, is the big opportunity.

Understanding the business models

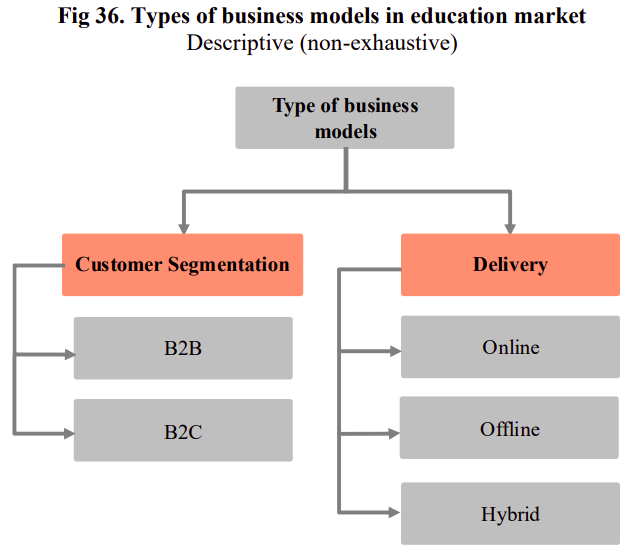

If you’re operating in India’s education market, there are a few different ways to play the game.

You can go direct-to-student (B2C) — delivering educational content through digital platforms or by running your own brick-and-mortar centers. Or you can go the B2B route, working with schools, colleges, or corporates to provide customized solutions.

Business models also differ by mode of delivery. Some stick to the traditional offline setup — physical classrooms like the schools we all went to. Others go fully online, delivering learning through apps, websites, and virtual classrooms. Then there’s the increasingly popular hybrid model, where most of the learning happens online, but students also get in-person support — say, through doubt-clearing sessions or weekend classes.

Regardless of which model you pick, the fundamentals of building a strong education business don’t really change.

First, you’ve got to figure out scale. Education is a one-to-many game — one teacher, one class, hundreds of students. Done right, your costs don’t rise in step with your revenues, and that’s the real key to making profits.

Second, you need to keep customer acquisition costs (CAC) in check. In education, word-of-mouth is powerful. If you can build an engaged community, students start marketing you to their friends and that organic growth keeps expenses under control.

Third, the secret sauce is always great teachers. Platforms live or die on whether students feel engaged and understood. Good teachers build trust and keep learners coming back.

And finally, you’ve got to know who you’re really building for. A low-cost online package caters to one type of student, a high-priced offline centre to another. Each choice defines the boundaries of your addressable market.

Started from the bottom

The story of PW starts with, well, an engineering dropout with a YouTube channel.

Alakh Pandey had dropped out of his college because he was deeply unhappy with how things were taught there. So, he started teaching physics — a subject he deeply loved — in small coaching centres in Allahabad. Soon after, in 2016, he also uploaded free physics lectures to his newly-started YouTube channel called PhysicsWallah. That one seemingly-small decision would be a force multiplier for Pandey.

Curious students came to his channel for clarity, then stayed and spread the word. The channel gained traction, grew into millions of followers, ventured into courses other than physics, and by 2018 it became an app. By 2020, the hustle formalized — PhysicsWallah became a registered edtech company. And Pandey was the face of it.

Today, PhysicsWallah (PW) is a B2C powerhouse offering test-prep courses for competitive exams across every delivery method: pure online, pure offline, and a mix of both.

On the online side, students can sign up through PW’s website (launched in 2018) or app (rolled out in 2020). Once enrolled, they get access to live lectures, recorded sessions, doubt-solving, and a host of digital learning resources. This is the low-cost, high-scale model that first put PW on the map.

But PW isn’t just an online player anymore. It has diversified to offline in a big way — a pivot that mirrors much of the industry. That’s because offline channels simply have much higher ARPU, resulting in fatter margins for the companies.

Pandey doubled down on this strategy, even claiming in an interview that the company would open “as many offline centres as it can” in FY25, even if it eats into profits. Is that overconfidence fuelled by the hunger to grow, or simply high conviction? The answer may decide whether PW avoids the fate of Byju’s or charts a very different path.

Either way, the shift is already visible in the numbers: what used to be a 60:40 revenue split in favour of online two years ago is now almost 50:50.

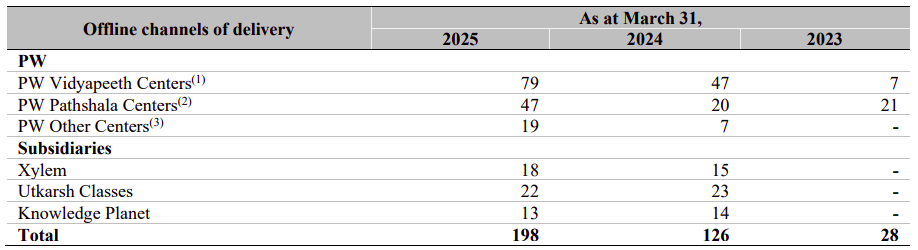

To get there, PW built out two kinds of physical centres (along with subsidiaries):

PW Vidyapeeths — large-format coaching hubs in tier-1 and tier-2 cities.

PW Paathshaala — smaller, more affordable setups designed for tier-3 and tier-4 towns.

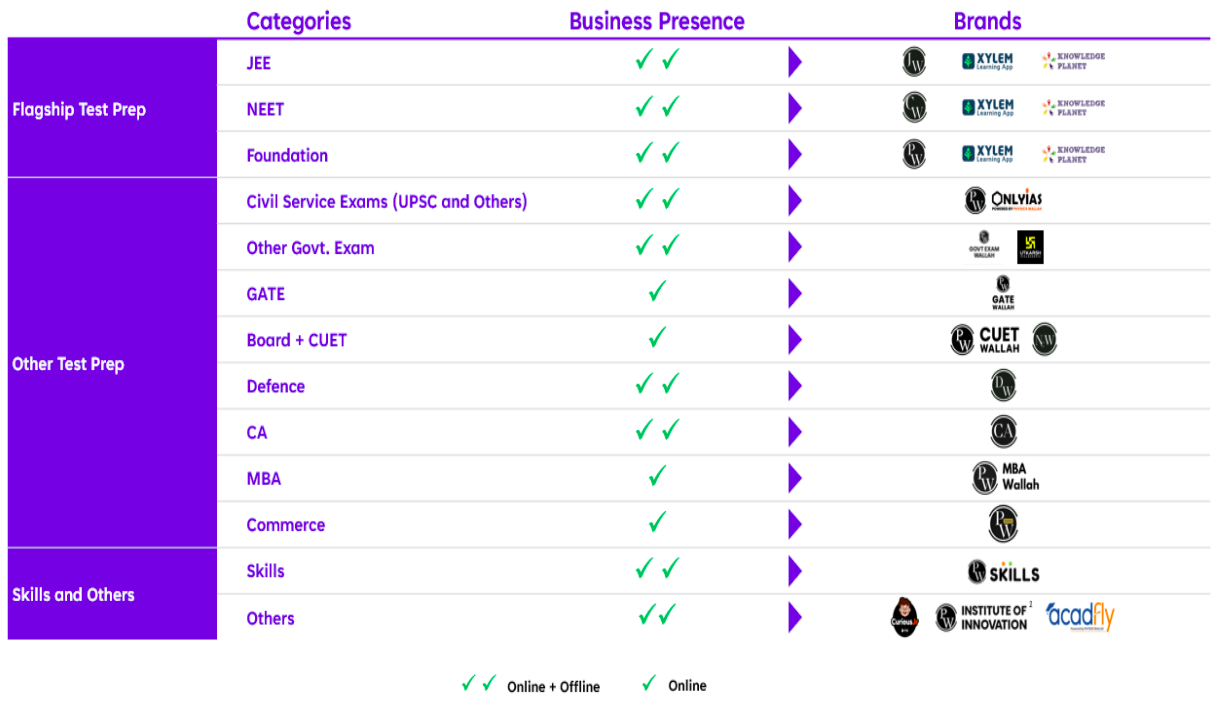

And the diversification hasn’t just been in delivery channels. While PW started with science-based undergraduate tests like NEET and JEE, it realized that it could replicate a similar playbook for post-graduate, non-science exams like CAT and UPSC. Some of these attempts may have failed, but the overall strategy of casting a wider net succeeded. Within 2 years, the share of NEET and JEE in PW’s user-base fell by nearly half to 35% as the share of the rest increased.

This growth across channels, geographies, and categories has been powered by a spree of acquisitions. It started in 2022 with iNeuron, an online skilling platform in IT and sciences — it failed, forcing PW to book a loss. Around the same time, it also picked up OnlyIAS to capture a space in the UPSC test-prep market. In 2024 came Xylem Learning, a Kerala-based multilingual edtech player, giving PW a strong presence in South India.

Put together, these deals show a clear strategy: go deeper into competitive exams, diversify into skilling, and expand offline across India.

Yet, despite all this, PW has somehow retained the soul of being just a YouTube channel, and that shows up in how important online still is for them. About 95% of its 46 million students first signed up online. Search for any science topic on YouTube and chances are, one of the top-ranked clips will be from PhysicsWallah. Many of those students get attracted by the online stuff enough to land up in PW’s offline centres.

As PW’s cofounder Prateek Maheshwari explains: “From a business standpoint, our offline and online operations are closely linked. YouTube plays a critical role in offline lead generation; it is essentially a free student acquisition funnel.” He even calls it the 3C principle: content, community, and commerce. Nail the first two, and the third will follow.

The funnel is real — about 70% of PW’s offline students had already engaged with its online platform before joining a centre. The rest came in through old-school methods like seminars and teacher interactions.

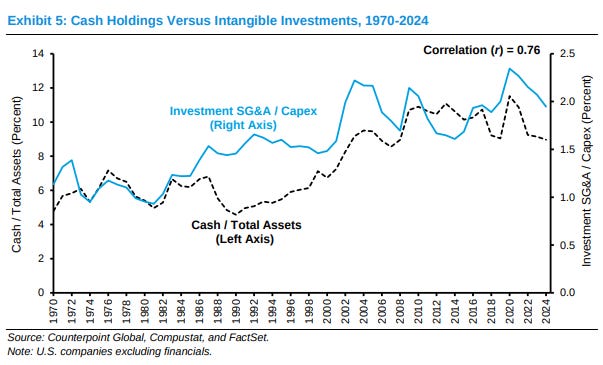

PW takes its content and community-building seriously — and the spending reflects it. Marketing eats up about 10% of revenue, which is actually moderate in an industry where ad spends can spiral out of control. Fun fact: ~23% of the new money PW is planning to raise will specifically go towards marketing.

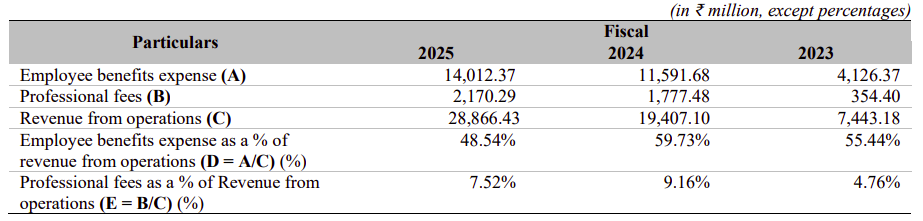

But, the biggest cost, by far, is teachers. They are the product, the face, and the delivery channel rolled into one. If the teachers are great, the experience is great. If they leave, students leave. Teacher costs alone are over 55% of revenue, whether booked under “employee benefits” (payroll) or “professional fees” (consultants). And attrition is a material risk — 25–35% every year. In March 2023, five JEE and NEET faculty members left to start a rival offering. In January 2024, eleven GATE faculty members defected to a competitor.

Let’s talk numbers

Now for the part investors actually care ji about — the numbers.

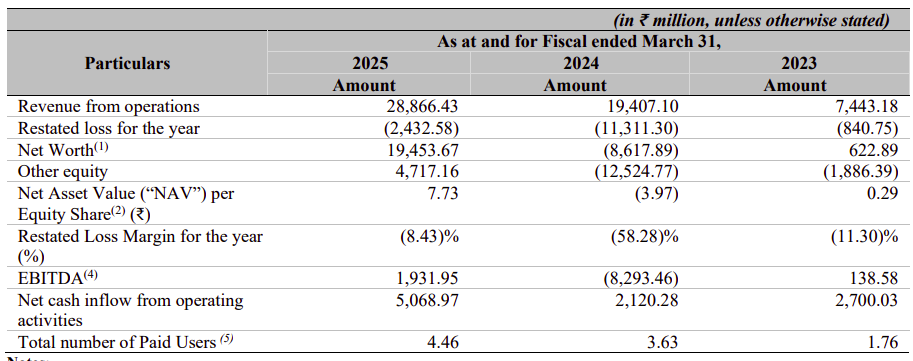

PhysicsWallah’s revenue has been growing fast. In FY25, it clocked about ₹2,887 crore, a nearly 49% jump from the previous year. The offline business has been the big driver here, contributing ₹1,352 crore, up from just ₹281 crore two years ago. Online still delivers scale — millions of paying users — but offline brings the money.

The problem is costs are growing nearly as fast. Employee expenses alone rose 21% to ₹1,401 crore, while advertising and publicity costs jumped 41% to ₹276 crore. Put simply, every rupee of extra revenue is being matched — sometimes outpaced — by rising expenses.

And that’s why profits still aren’t showing up. PW posted a net loss of ₹243 crore in FY25. To be fair, that’s an improvement — the loss shrank by almost 80% compared to FY24. The earlier year looked particularly messy because of accounting quirks (like fair value adjustments on CCPS and ESOPs) and goodwill write-downs from underperforming acquisitions. Strip those out, and the core business isn’t bleeding as heavily as the headline numbers suggest, but it’s still bleeding.

And given that going heavy on offline expansion through acquisitions is the modus operandi, we can’t ignore the fact that these physical centres typically take a couple of years to break even at the centre level before they start showing up as profits in the P&L. Which means turning a profit at the company level is still not visible — and that’s a risk every potential investor should keep in mind.

So what’s this IPO about? PW is looking to raise about ₹3,820 crore. Of that, ₹3,100 crore will be fresh equity (new shares issued by the company), while the remaining ₹720 crore is an offer for sale by the founders Alakh Pandey and Prateek Maheshwari — they’ll each cash out roughly ₹360 crore. Importantly, none of the external investors are selling right now; WestBridge, GSV Ventures, Lightspeed, and Hornbill are all staying put.

And what happens with the fresh money? PW wants to expand their offline distribution and make themselves a household name that everyone remembers. South India is one area they’d like to grow further in, so they’ll focus on expanding Xylem’s presence. And they’ll be putting in money into increasing server capacity.

In other words: the three things any edtech business needs: scale, word-of-mouth, and great teaching capability.

The Final Word

India’s university system can be brutal. There are lots of hopeful candidates who chase very few seats in reputed institutions. And in helping them chase that, PW went from being a mere YouTube channel to a listed education empire — a rare feat by any means.

The opportunity is massive, the growth is real, and the numbers show momentum. But the risks are just as real: teacher churn, offline expansion costs, and whether the aggressive growth is worth pursuing.

The IPO will be the market’s verdict. Is this the next great Indian education story, or just another ambitious coaching company riding on hype? We’ll soon find out.

Cash rules everything around companies

Cash is the lifeblood of a business. It’s essential for everything it needs: from it paying salaries on time, to seizing unexpected opportunities when they arise.

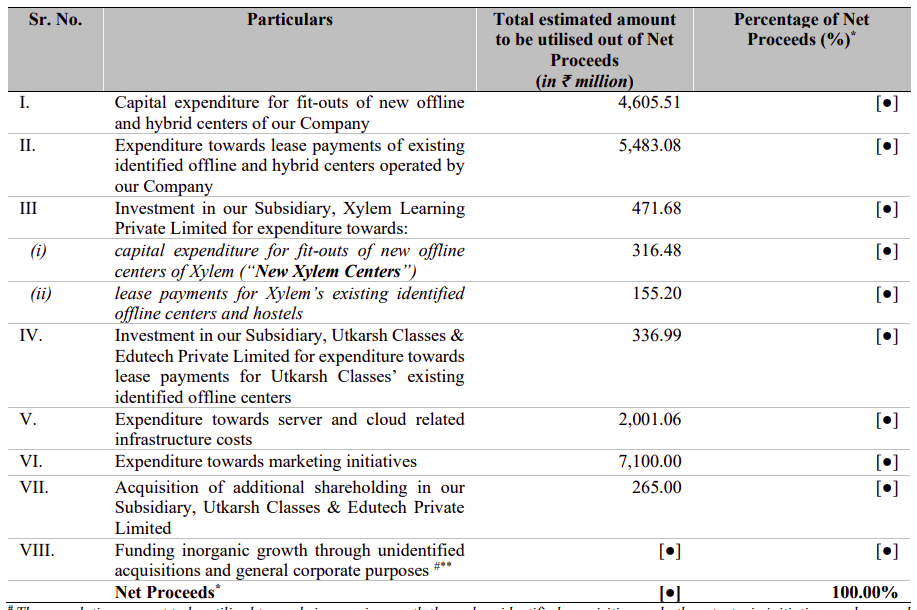

But lately (and interestingly), companies across the world have recently been holding way more cash than they might ever need. Listed US companies held nearly $2.5 trillion in just cash at the end of 2024 — about 4.7% of their total market cap. From 5.8% in the thirty years between 1970-2000, cash has risen to ~9.7% of companies’ assets between 2001-2024.

And this isn't just an American phenomenon. From Indian IT giants sitting on billions to European manufacturers stockpiling reserves, the global corporate cash pile has swollen to unprecedented levels.

What is really behind all this? A new report by Morgan Stanley pushed us to start thinking about this question. And it led us down a giant rabbithole on why companies want cash, how they use it, how they abuse it — and above all, just how weird it all is.

Industry matters

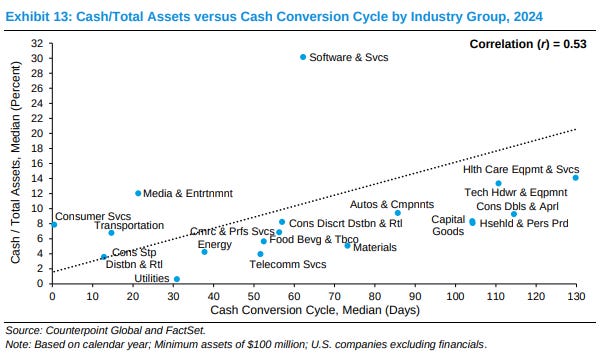

Here’s one insight: different industries hoard different amounts of cash.

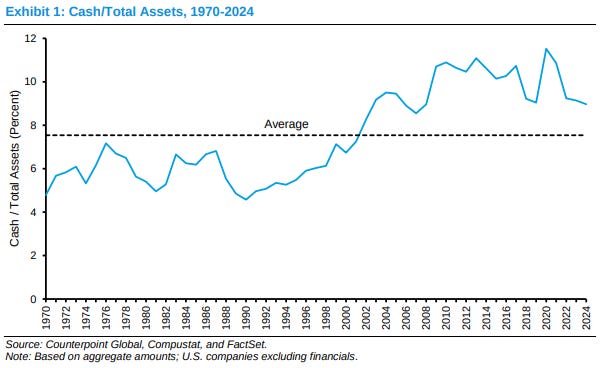

Pharma and biotech firms top the charts — over 55% of their total assets are held in cash, or in other assets that can quickly be turned into cash. Software companies, too, hold more than 30% of their assets in cash.

At the other end of the spectrum, traditional industries like energy, at 4%, and utilities, at less than 1%, maintain far leaner cash positions.

Why do entire industries have such distinct behaviour?

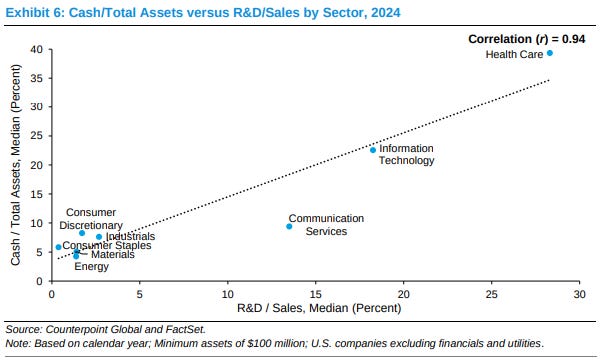

Well, that’s perhaps because different industries have different sorts of assets. Traditional companies have large reserves of tangible assets, like buildings or machines. More new age companies, on the other hand, are likely to have intangible assets — like algorithms, or patents.

Now, if you need cash in a pinch, you’re much better off with tangible assets. You can pledge them as collateral, and get a quick loan. In case you default, a bank can quickly sell these, and make themselves whole. That simply isn’t the case with intellectual property like medical patents — especially when they haven’t been converted into real drugs.

On the flip side, companies that invest in a lot of R&D are likely to have a lot more cash. If you run a pharma company, for instance, and expect to have a long drug development pipeline, you need a lot of cash to stay afloat until you find the right opportunity.

That’s partly why companies have so much more cash these days. Since the 1970s, American companies have been investing far more in intangibles like patents and other forms of knowledge. And that’s around when companies started holding on to more cash.

Working capital dynamics, too, can play a role here. If you have a long cash conversion cycle — the time between when you pay suppliers, and when you collect money from customers — you’re likely to hold more cash as a buffer.

Age comes for everything — including companies

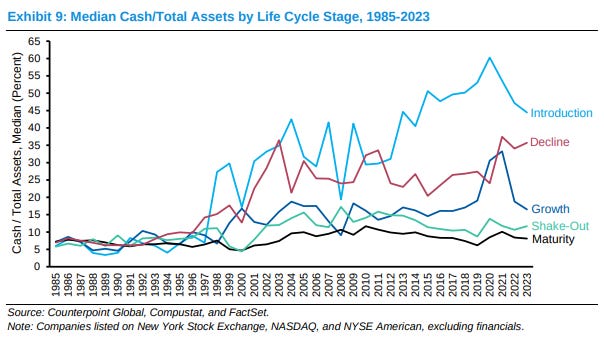

You would expect the age of a company to matter a lot. Mature firms enjoy better access to credit markets, more predictable cash flows, and established relationships with big banks. They’re likely to find it easier to get all the cash they need. Which is why you’d expect them to have less cash than a young, untested company.

But the data tells a more nuanced story.

Companies follow a U-shaped pattern of cash holdings across their lifespan:

Firms in the introduction stage hold the most cash — with cash making up nearly a third of their assets. This is perhaps because they raise a lot of money, and then slowly burn through it all developing new products, and building their market.

As companies mature, with established operations and steady cash flows, their cash holdings drop to just 8% of their assets.

But towards the end, in their dying breaths, more than a fifth of a company’s assets are held in cash.

This said, no matter how old a company, their cash holdings have simultaneously increased in recent years.

Why is that? The most important answer to that lies in crises.

Hard times create strong firms, strong firms create good times

Ordinarily, a company’s cash does little beyond serving as a buffer. But then, you run into a bad time, and that cash becomes your sole lifeline.

Over the last two decades, companies across the world faced two crises that brought business to a standstill. The first was the global financial crisis of 2008. The other was the CoVID-19 pandemic. And those taught many businesses the importance of cash.

In the financial bloodbath in 2008, for instance, firms that began with thin cash reserves suddenly found themselves in a mess they couldn’t dig themselves out of. They had to cut costs drastically, defer investments, and take expensive emergency loans. Companies with ample cash reserves, by contrast, could maintain operations as usual — even making opportunistic investments as asset prices fell all around them.

You can see something similar with India’s biggest companies. A study of Nifty-50 companies between 2007–2021 found that during a crisis, their cash holdings dropped considerably — meaning they were actively using their cash to survive or stabilize operations. Their average cash-to-asset ratio fell from 13% normally to around 11% during both crises.

But cash isn’t just useful for surviving a crisis. Warren Buffett calls cash "a call option with no expiration date". And you can see that principle at action, with his company, Berkshire Hathaway. During the 2008 financial crisis, for instance, the company brought its massive cash reserves to bear on the market, investing $5 billion in Goldman Sachs and $3 billion in General Electric at bargain prices — investments that proved enormously profitable as markets recovered.

Is there such a thing as too much cash?

Holding too much cash, though, has costs of its own.

The most obvious is opportunity cost. Every Rupee that’s sitting idle in your accounts is a Rupee that isn’t at work bringing returns for you. You’re probably just making a paltry bank interest.

But there’s another unintuitive, yet interesting concern: the theory of agency costs, proposed by Harvard economist Michael Jensen. When a company has too much cash and little debt to repay, its management might get wasteful — using cash in a way that is against shareholders but might serve their own interests. They might, for instance, make costly acquisitions that make them look good, but bring poor returns. Debt, interestingly, can have a disciplining effect: companies that must constantly think of paying back their debts are likely to use their money better.

A third concern is that your cash holdings can affect your market perception. If a company accumulates more cash than its peers or its own needs, investors may see it as a signal of lacklustre prospects. After all, if the firm had great investment opportunities, wouldn’t it deploy that cash rather than stockpiling it?

The worse your corporate governance seems, the more brutally the market punishes you. Well-governed firms see their cash valued at close to face value by investors. Poorly-run companies see their cash holdings valued at steep discounts.

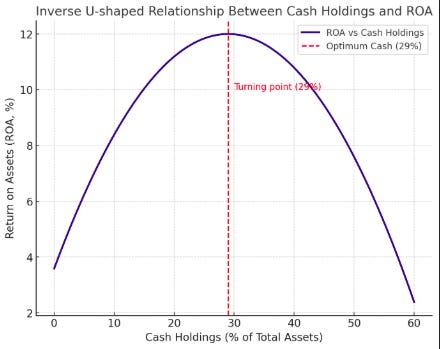

There are, in fact, certain optimal levels of cash for companies. A paper by three Australia-based researchers finds that cash improves firm performance up to a point, after which, it declines. That point, to them, is 29% of assets: below that, the return on assets improves. More than that, returns fall. In other words, there’s an inverse U-shaped curve to how much cash you should have.

Different geographies, different cash

What a company does with its cash, often, is a matter of where it is.

In developed countries, cash and debt levels are negatively correlated — if you can access cheap loans, you’re likely to have less cash on hand.

In India, on the other hand, cash and debt are positively correlated. Unlike the developed world, we don’t have well-developed finance markets where firms can access credit quickly and cheaply. With our high interest rates, Indian firms face a higher chance of falling into financial distress. And so, well-run Indian companies are more likely to keep cash at hand. For Indian companies, cash makes up 12% of their assets — much higher than 9% for U.S. firms.

Others have it worse. For Chinese companies in the 2000s, that same ratio was a whopping 20%. For developing countries, access to external funds can be deeply uncertain — and political — and can dry up very quickly when the times are rough.

But it gets even weirder. A paper by Ravinder Kumar Arora finds that in India, firms with excess cash that see profitable investment opportunities shockingly spend less on capital expenditure than those with excess cash but poor investment opportunities. The existence of investment opportunities reduces one’s propensity to invest!

Cashing out

All of this is a glimpse into a simple fact — cash is a strange commodity.

It’s bad to have too little. It’s bad to have too much. Not having cash could ruin you in a crisis. Having cash might make your company look like it’s run out of options. There is, perhaps, an ideal level of cash that a company might want. How much, however, can vary — by the industry, by the age of a company, and even where it does its business.

The line between prudent cash management and excess hoarding, clearly, is thin — and will continue to shift. The companies that will perform best, though, are those that’ll identify that line, and know how to tread it skillfully.

Tidbits

Adani Power and Bhutan’s Druk Green Power Corporation (DGPC) have inked agreements to build the 570MW Wangchhu hydroelectric project at an investment of ~₹6,000 crore. The plant will run on a BOOT (Build-Own-Operate-Transfer) model, with construction starting in early 2026 and completion expected in five years. Designed as a peaking run-of-river facility, it will supply Bhutan’s winter demand while exporting surplus power to India in summer.

Source: Business Line

Akasa Air has overtaken SpiceJet to become India’s third-largest airline by revenue just three years after launch. In Q1 FY26, Akasa reported ₹1,399.6 crore in revenue, while SpiceJet slipped to ₹1,059.8 crore. Market share tells the same story — Akasa at 5.5% compared to SpiceJet’s 2%. SpiceJet, on the other hand, is battling shrinking revenues, delays in staff salaries, and a dwindling fleet of which only 40% is operational.

Source: Mint

A new US Senate bill called the HIRE Act proposes a 25 percent tax on American companies that outsource work to foreign countries like India. This could significantly impact India's 100-billion-dollar IT export industry, which relies heavily on contracts from US firms like TCS, Infosys, and Wipro. The tax money would fund American worker training programs, with the rules taking effect from January 2026 if passed. Still, experts say the passage of this bill is unlikely.

Source: The Hindu

India's Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced on Friday that the government will roll out a relief package to help exporters hurt by steep US tariffs that have reached as high as 50 percent on Indian goods. The package will include measures to "handhold" affected industries, with the government planning to offer credit guarantees on loans for small businesses and exporters hit by the tariffs.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Manie

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

We just started a new experiment - Plotlines?

Plotlines is an extension of our Chatter newsletter. While most financial analysis focuses on quarterly results and near-term changes, Plotlines takes a different approach. We analyze executive commentary from earnings calls and investor presentations to identify long-term, structural shifts that will shape industries for years to come.

Instead of chasing headlines, we look for strategic pivots, evolving competitive dynamics, and fundamental changes in how companies allocate capital. Each week, we'll highlight the most significant "plotlines" from recent corporate communications, focusing on comments that signal permanent changes in market structure, technology adoption, or business models.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

I have seen the the boom and bust cycles of Bansal, Resonance, Aakash, and more recently Allen. They all did something right for a while. But this coaching space is - tbh - similar to a service industry as your scaling requirements are directly dependent on teachers. So well it’s the teachers who are the product.

Without teachers you can’t do much so all this IPO and brand - somehow deep down - makes me feel PW will also see the strain in the coming future.

Well good for Alakh and his peer, they will get their money out. But as the scale of these “services” increases - the quality has to go down.

I generally am ominous about this industry as a whole.

I actually feel the coming generation would do better by working towards and getting involved with good startup incubators like TiE and bring in the entrepreneurial spirit.

Well well, I hope the investors of PW don’t read my comment 😅😋