From $22 Billion to Nothing: The Catastrophic Fall of Byju’s

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

Today on The Daily Brief:

Byjus without juice

Another one bites the dust ft. Navi

Rising Rubber Prices May Erase Gains for Investors

Byjus without juice

On October 17, 2024, Byju Raveendran, the founder of Byju’s, dropped a bombshell: the company—once valued at an eye-watering $22 billion—is now worth nothing. Byju’s, once hailed as the crown jewel of India’s booming edtech sector, has come crashing down. This dramatic collapse has left everyone wondering, “What went wrong?”

Let’s walk through the story of Byju’s—its meteoric rise and the chain of events that led to its downfall.

The rise of Byju’s

Byju’s started as an educational technology company, offering online learning solutions primarily for school students. With engaging videos, interactive lessons, and a mobile app, it brought a fresh, exciting approach to education. At its peak, Byju’s became one of the world’s most valuable startups in the education space. But beneath this success, cracks were forming that would eventually bring the company down.

How Byju’s grew so fast

The company’s rapid growth came from two things: aggressive acquisitions and huge investments from big-name backers. Between 2019 and 2021, Byju’s went on a shopping spree, buying over two dozen companies. Notable among them were WhiteHat Jr., a coding platform for kids, acquired for $300 million, and Aakash Educational Services, a test prep giant bought for nearly $1 billion.

These deals looked promising. WhiteHat Jr. gave Byju’s a foothold in the booming coding education market, while Aakash strengthened its presence in the traditional exam prep space. But integrating these businesses proved much harder than expected. Running so many operations under one umbrella stretched the company thin, and many of the acquired businesses struggled to turn a profit, draining Byju’s resources.

Cash burn, expansion gone wrong, and legal trouble

Byju’s growth came with a heavy cost. The company burned through cash at an unsustainable pace. Investors like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and Tiger Global poured billions into Byju’s, but the company spent the money just as quickly.

This strategy worked during the pandemic, when online education was booming. But as schools reopened and the pandemic’s impact faded, demand for online learning dropped. Meanwhile, new funding started drying up, leaving Byju’s in a liquidity crisis—it simply didn’t have enough cash to keep things running smoothly.

On top of that, legal troubles piled up. In September 2024, a Delaware court placed several of Byju’s U.S. subsidiaries into involuntary Chapter 11 bankruptcy. This happened because the company failed to provide key financial information to its creditors. Things got worse when it was revealed that Byju’s had transferred $700,000 between U.S. subsidiaries without proper authorization, violating bankruptcy laws. Allegations of financial mismanagement deepened the crisis, with claims that the company had hidden $533 million in cash outside the U.S.

As if that wasn’t enough, Byju’s legal battles extended to its own defense. Two U.S. law firms representing the company tried to withdraw from the case, saying their relationship with Byju’s had broken down and that the company wasn’t cooperating. This lack of cooperation exposed deeper internal issues, including governance problems.

Problems with products and sales tactics

Byju’s wasn’t just facing financial and legal trouble—it had product issues too. Parents who bought into Byju’s promises of high-quality education were disappointed. Many felt pressured into buying expensive learning packages that didn’t deliver the value they expected.

The company’s rush to diversify also led to a decline in the quality of its core products. By trying to do too much, Byju’s lost sight of its original focus—providing meaningful educational experiences. This growing customer dissatisfaction only made things worse for its already shaky reputation.

Governance and transparency issues

Governance problems were another major factor in Byju’s downfall. In 2023, key investors, including Prosus Ventures and Deloitte, resigned from the company’s board, citing concerns about how it was being managed. A lack of financial transparency made it harder for Byju’s to raise funds, and investor trust eroded quickly.

Things hit rock bottom in early 2024 when Byju’s tried to raise $200 million through a rights issue. But the company’s valuation had fallen to just $20 million—a shocking 99% drop from its peak of $22 billion. Unsurprisingly, investors were reluctant to participate, further diluting the company’s equity.

Internal chaos and the impact of COVID-19

The rapid expansion also created internal chaos. Over the past two years, Byju’s laid off thousands of employees in a bid to cut costs and stay afloat. The layoffs were a clear sign that the company had struggled to integrate its acquisitions and streamline operations.

Byju’s thrived during the COVID-19 pandemic, as students shifted to online learning. But once schools reopened, the demand for online education plummeted. Byju’s business model, which depended heavily on rapid growth, wasn’t built to handle this shift.

The company had planned to go public through an IPO in 2021, aiming for a valuation of up to $50 billion. However unfavorable market conditions forced Byju’s to delay the IPO, cutting off a critical source of funding that could have helped stabilize its finances.

Lessons from Byju’s collapse

Byju’s story serves as a cautionary tale for the edtech industry and startups in general. The company’s downfall shows that even the most promising ventures can crumble if they lose sight of the basics—sustainable growth, good governance, and delivering real value to customers.

Byju’s meteoric rise was built on aggressive expansion and easy money, but the cracks became impossible to ignore when the tide turned. Without a focus on sustainability, transparency, and customer trust, even the brightest stars can fall—and fall hard.

For now, Byju’s journey from a $22 billion success story to nothing is a stark reminder of the challenges that come with rapid growth. It’s a lesson that sustainable business practices and responsible governance are not optional—they’re essential for long-term success.

Another one bites the dust ft. Navi

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) recently barred Navi Finserv, owned by Sachin Bansal, along with three other financial institutions, from issuing new loans. This ban takes effect on October 21, 2024, and everyone’s talking about how it could shake things up for how NBFCs operate in India.

So, what exactly happened, and why? Let’s break it down in simple terms.

These companies, including Navi Finserv, were found charging borrowers extremely high interest rates and not following the RBI’s rules on fair pricing.

Now, what’s fair pricing? It’s just a way of saying that interest rates and fees should be reasonable, easy to understand, and aligned with regulatory standards. The RBI’s goal is to protect borrowers from being overcharged with hidden fees or excessive interest rates.

To ensure this, the RBI rolled out stricter rules in 2022, focusing on digital lending platforms—mainly fintechs—because they often offer quick loans online. The concern was that some of these companies were taking advantage of borrowers by charging unfair rates.

Navi Finserv grew rapidly, and most of its business comes from unsecured loans. In fact, nearly 90% of its loans are personal loans, meaning borrowers don’t have to pledge anything as collateral. While that makes things easier for borrowers, it also makes these loans riskier for lenders.

With its loan book worth nearly ₹12,000 crores, Navi’s income heavily depends on lending. So, this ban on issuing new loans is a setback for the company since loans are its main source of revenue.

Even though Navi recently hired a former RBI Executive Director, Anil Kumar Misra, to strengthen its compliance, this RBI action shows there’s still work to do.

But Navi’s case isn’t the only one. The RBI has been tightening its regulations on financial institutions, especially NBFCs, fintechs, and digital lenders, over the past few years.

December 2020: RBI stopped HDFC from issuing new credit cards and launching digital products after repeated IT outages. HDFC had to fix these issues before the ban was lifted in March 2022.

March 2023: Axis Bank was fined ₹1.91 crore for compliance issues, including improper KYC practices and loan handling.

November 2023: Bajaj Finance was banned from offering products like Insta EMI due to violations of digital lending rules. These restrictions were lifted once they resolved the issues.

February 2024: Paytm Payments Bank was blocked from onboarding new customers due to KYC and cybersecurity issues.

August 2024: The RBI introduced new rules for peer-to-peer (P2P) lending platforms. These platforms connect individual lenders with borrowers, offering an alternative to traditional bank loans. But many platforms failed to properly screen borrowers, and some misled lenders with promises of guaranteed returns. RBI’s new rules banned credit guarantees, required lenders to approve loans individually, and mandated that funds be transferred within T+1 days—or returned if not disbursed. P2P platforms were also stopped from marketing themselves as investment products.

This growing crackdown reflects the financial sector’s concerns about the risks tied to unsecured lending. For example, Axis Bank, despite reporting an 18% profit increase in its latest earnings, acknowledged that defaults on unsecured loans—like personal loans and credit card debt—are rising.

The RBI’s action against Navi Finserv is part of a broader effort to protect borrowers and keep the financial system healthy. With unsecured loans under the spotlight, we can expect more steps from the RBI to manage risks and ensure lenders play fair.

Rising rubber prices may erase gains for investors

Let’s talk about an issue that has Indian tyre companies worried—the soaring prices of natural rubber.

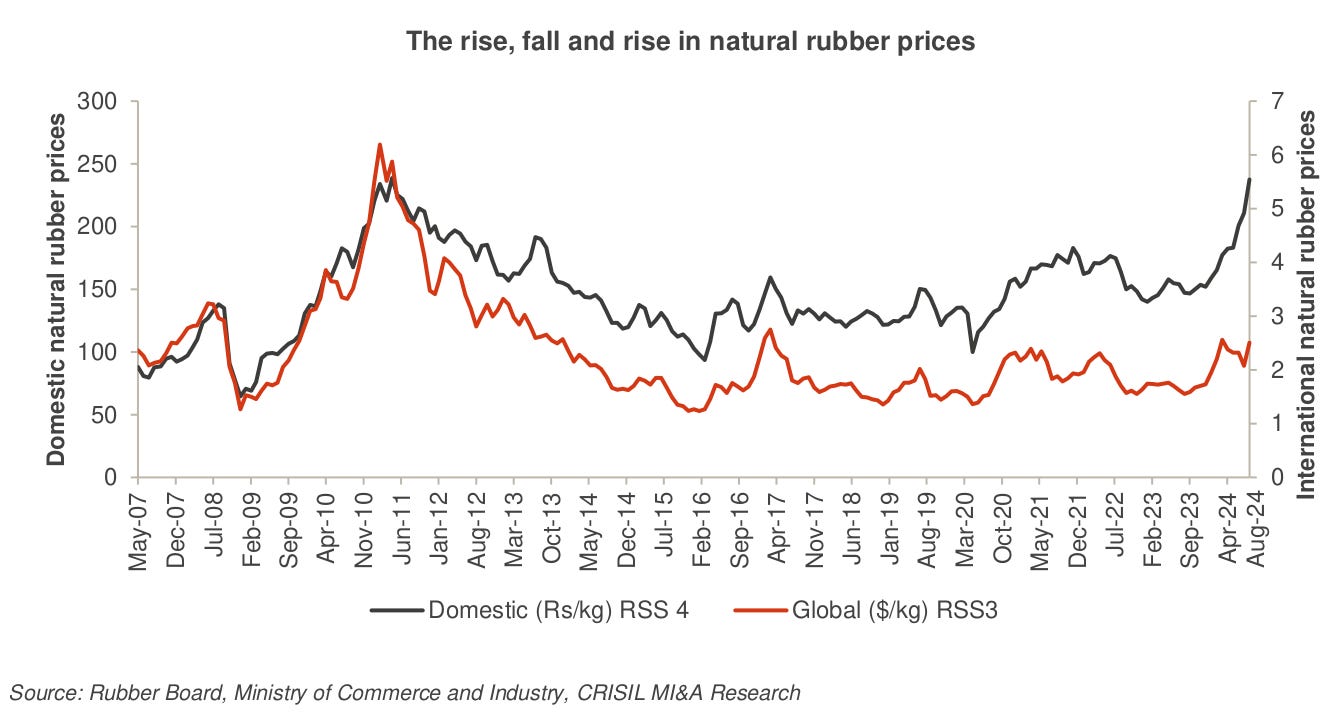

Rubber prices are at their highest in 13 years, and it’s starting to hit the tyre industry hard. But before we dive into how this impacts tyre makers, let’s break down what’s really happening.

To put it simply, natural rubber—a key ingredient in making tyres—has gotten a lot more expensive. Back in 2011, rubber prices crossed ₹200 per kilogram, mainly due to the effects of the global financial crisis. Governments and central banks were pumping money into their economies to revive growth, which drove up demand for raw materials like rubber. After that, prices settled down, hovering around ₹150/kg on average for about a decade.

But here we are in 2023, and rubber prices have surged past ₹200/kg again. This time, it’s not just a temporary spike. There’s a deeper problem—a persistent supply-demand imbalance that’s making it hard for prices to come down.

So, what’s causing this mismatch?

Demand for rubber has grown faster than supply. According to CRISIL, rubber production increased by around 35% between 2011 and 2023. That sounds decent, but here’s the catch—demand rose by 40% in the same period. That small but steady gap is creating strain in the market, driving prices higher.

How did we get here?

Let’s rewind to 2011. Back then, countries like Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia led the world in rubber production, accounting for about 80% of the global supply. The high prices encouraged farmers to plant more rubber, even in India, where production peaked in 2013 at around 913,700 tonnes.

But things changed when prices stagnated after 2013. With profits shrinking, farmers began switching to other, more lucrative crops. As a result, the total area under rubber cultivation stopped expanding after 2015. To make things worse, many rubber trees started aging, producing less latex, which further slowed down production.

While production lagged, demand kept growing. Central banks worldwide continued their easy monetary policies, fueling economic growth—and the need for rubber. However, planting more rubber trees isn’t a quick fix since they take 6–8 years to mature. So, even if new trees are planted now, supply won’t catch up fast enough. As it stands, supply is only growing by 1-2% annually, while demand is rising by 3-4%. If this continues, a more serious shortage could hit by 2024.

How does this impact tyre companies?

Tyres are made using a mix of materials, but natural rubber is one of the most essential—and expensive—ingredients. Indian tyre manufacturers, unfortunately, don’t have enough domestic rubber to meet their needs. In 2023-24, India’s rubber production was around 8.57 lakh tonnes, while demand hit 14.16 lakh tonnes.

This gap forces tyre companies to rely on imports. However, importing rubber isn’t cheap because India imposes a 25% customs duty or ₹30 per kg (whichever is higher) on rubber imports. Interestingly, even with the duty, imported rubber is often cheaper than buying it locally since global prices tend to be lower than domestic ones.

But this isn’t a sustainable solution. If imports remain more attractive, local farmers will have even less incentive to grow rubber. And without increased domestic production, India will stay dependent on costly imports.

So, what’s being done to address this?

Tyre companies are lobbying the government to reduce customs duties on rubber imports, but so far, there’s no change in policy. The government’s focus is on boosting local production to reduce reliance on imports in the long run.

To meet this goal, the Rubber Board of India, the Automotive Tyre Manufacturers’ Association, and the government have launched a project to expand rubber cultivation in the Northeastern states. Right now, most of India’s rubber comes from Kerala and Tamil Nadu’s Kanyakumari district, covering about 5 lakh hectares. The hope is that expanding rubber farming in the Northeast will help meet rising demand.

In the meantime, tyre companies are already feeling the squeeze. CEAT, for example, reported in its latest earnings that rising rubber prices are cutting into their profit margins. While importing rubber has provided some short-term relief, it’s not a long-term fix. If tyre makers can’t find a way to manage these rising costs, they’ll face more challenges ahead.

In summary, the natural rubber market is in a tough spot. Supply can’t keep pace with demand, and relying on imports isn’t a sustainable option. The key to solving this problem lies in boosting local production, but that takes time and patience—rubber trees don’t grow overnight.

Tyre companies will need to carefully manage their costs and push for policies that support sustainable growth in India’s rubber industry. Otherwise, they’ll continue to struggle with higher raw material costs, squeezing their profit margins for years to come.

So, while rubber may seem like just another commodity, it plays a critical role in industries like tyre manufacturing. And if this supply-demand mismatch isn’t fixed, the ripple effects could spread across the economy.

Tidbits

Inflows into gold ETFs jumped by 88% in 2024, totaling ₹1,232.99 crore. The surge was driven by rising gold prices and a shift toward ETFs over physical gold due to concerns about storage and liquidity. Expectations of U.S. Fed rate cuts also fueled demand.

Adani Enterprises raised ₹4,200 crore through a Qualified Institutional Placement (QIP) that was oversubscribed 4.2 times. The funds will support growth in the infrastructure and energy sectors, reflecting strong investor confidence.

The Karnataka government is planning a 1-2% transaction fee on food delivery platforms like Zomato and Swiggy. The additional fee will help fund welfare programs and social security for gig workers. However, it may result in slightly higher costs for consumers.

The Coastal Shipping Bill 2024 eliminates the need for Indian-flagged vessels to obtain trading licenses for coastal operations. While this move aims to reduce costs and boost domestic shipping, industry leaders are calling for further tax relief to ensure sustained growth.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

If you have any feedback, do let us know in the comments

BYJU’s is a classic case of why startup valuations should be taken with a grain of salt. Great article 💪