Digging through the RBI annual report

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Inside RBI’s Annual Report 2025

Climate Change I: Why India must invest in resilience

Inside RBI’s Annual Report 2025

The Reserve Bank of India released its 2024-25 annual report. As you'd expect, every financial publication and analyst has gone about summarizing the headline numbers. Household savings are up, RBI surplus transfers hit record highs, digital currency adoption growing… you've probably already seen all of that.

But beyond those loud headlines, the report also has little nuggets of gold; little research studies buried within that give us important insights about the Indian economy — everything from what's driving productivity growth, to how companies think about borrowing, to where Indian capital is flowing globally, to how the central bank is preparing for uncertainty, to India's approach to international payments.

Instead of giving you another summary, we wanted to pick those nuggets out for you. In the annual report the RBI had published research oLet's explore what the RBI's researchers have discovered.

The Innovation Gap

Let's start with research and development spending – where the RBI's analysis reveals both progress and a concerning reality about India's innovation capacity.

The RBI's study shows that R&D investment has the biggest impact on large firms and high-tech industries. But here's the challenge: India spends just 0.7% of GDP on R&D. That’s a pittance when you compare us to the world’s major economies. Israel leads globally at 6.0%, South Korea spends over 5%, the US 3.4%. While those are the outliers, most developed countries spend over 2% of their GDP on R&D.

It’s not that we’re making no progress. Official data shows India's gross expenditure on R&D doubled from Rs 60,197 crore in 2010-11 to Rs 1,27,381 crore in 2020-21. The government has announced a corpus of Rs 1 lakh crore for research and innovation. But there's a structural issue the RBI highlights: the government pays for 50% of R&D spending in India, while in other countries, private companies usually lead the way.

The RBI's research on India, specifically, found that every one percentage point increase in R&D spending leads to about a quarter percentage point rise in productivity growth. And our lower level of development shouldn’t be an excuse. In fact, the study discovered something particularly interesting – middle-income countries like India actually get more bang for their buck from R&D spending compared to both low-income and high-income countries. We're in a sweet spot… if we can get the policies right.

Within Indian manufacturing, the RBI found that high-tech firms see the biggest productivity gains when they invest in R&D. That’s especially true when they also import advanced inputs and machinery. Advanced economies are simply better at turning research spending into actual innovation – they have better systems to absorb and apply new knowledge. Our firms can import the fruits of their labour. In fact, RBI’s research also shows that in countries like India that are still building innovation infrastructure, knowledge that comes from foreign companies or imports often has a bigger impact than domestic R&D spending alone.

We’re making slow progress. India ranks 39th globally in the Global Innovation Index 2024, up from 81st in 2015. But we need better institutional frameworks to convert research investment into economic growth.

The Credit Revolution

The RBI's research on what drives companies to borrow money reveals how India's financial system is quietly transforming.

The study's key finding is this: larger companies are less likely to borrow from banks, challenging conventional thinking.

This is mainly because bigger firms have better internal cash flows and more funding options. They can access what economists call "market-based funding" — that is, issuing bonds, commercial paper, or selling shares instead of taking bank loans. That's typically cheaper and gives companies more flexibility than traditional bank credit. When bank loan costs get too high relative to other options, companies — especially in services — switch to these cheaper market alternatives.

This represents a structural shift, as India's bond markets grow, and corporate credit markets become more sophisticated. Companies with higher debt loads are more likely to use non-bank funding when they want to expand or refinance existing debt. This shows India's financial system is becoming more sophisticated, and companies are actively managing their funding mix.

How did this happen? COVID-19 may have had something to do with it. Before COVID, companies with growing sales were more likely to take bank loans for expansion. But that relationship weakened after the pandemic. Companies became more cautious about bank debt, preferring to preserve cash or use alternative funding sources.

Companies with better cash flow and stronger ability to service debt still borrow more from banks. That makes sense; banks prefer lending to companies that can pay them back. But companies with good access to alternative funding sources are becoming less dependent on banks.

So, overall economic growth increases demand for business funding, but the relationship between growth and bank borrowing specifically is becoming more complex, as funding options multiply. Expect banks to increasingly focus on mid-market companies and retail customers, while large corporations migrate toward capital markets for their funding needs.

India’s Global Capital Push

The RBI's analysis of India's outward foreign direct investment shows how Indian companies are becoming more strategic about global expansion.

The data shows India's overseas investment increased significantly after the pandemic, with 51.1% now going to developed economies during 2019-2024. This marks a clear shift from the earlier focus on emerging markets.

Interestingly, the RBI research found that Indian companies strongly prefer investing in larger economies. Market size matters. The bigger the economy, the more attractive it is for Indian investment. This makes sense — larger markets offer better growth potential and more stable business environments.

The study shows something interesting about how Indian companies approach global markets. Companies that already export to a country are much more likely to invest there later. This suggests Indian firms often test markets through exports, before making the bigger commitment of direct investment. That reflects a smart, step-by-step approach to global expansion.

Geography matters, here. The RBI found that distance has a negative impact on investment decisions. Indian companies prefer investing in markets they understand, where business culture and practices are familiar.

On the other hand, research also reveals that countries rich in natural resources attract more Indian investment. Think about Indian companies investing in African mining projects or Middle Eastern energy ventures. In these cases, they’re trying to secure supply chains and essential resources, not just accessing new customers.

There are a variety of other factors Indians are careful about — from corporate tax rates, to economic factors, to geographic proximity, to institutional quality. It looks like Indian multinationals are becoming more selective, moving away from opportunistic deals toward strategic investments that offer genuine growth opportunities and supply chain security.

Managing Uncertainty

Let's discuss ‘reserve management’ — or how central banks manage their foreign currency holdings to ensure financial stability. The RBI's research shows how central banks worldwide are adapting to the increased geopolitical risks we see all around us.

Central bank surveys consistently show geopolitical tensions as the biggest worry for today’s reserve managers. The use of financial sanctions as a political weapon has completely changed how central banks think about managing foreign exchange reserves.

Central banks, these days, are trying to achieve three goals at once: keeping reserves safe, keeping them liquid so they can be used quickly, and earning decent returns. Traditionally, these goals conflicted -– the safest assets weren't always the most liquid, and liquid assets didn't always pay well.

Diversification, too, has become a top priority. Banks are trying to spread their reserves across different currencies, asset types, and countries, to reduce the risk of being too dependent on any single asset, or to any one country's political decisions. Gold has become increasingly important in this strategy. Central banks are buying more gold because it maintains value during crises, can't be frozen or confiscated like currency reserves, and provides genuine diversification away from any single country's currency.

Reserve managers are also paying more attention to environmental and social factors in their investment decisions. They aren’t doing this to look good, mind you — they’re trying to protect reserves against future disruptions.

For India, this research suggests the RBI is strategically building multiple layers of protection into reserve management, to prepare for a world where economic and political shocks happen more often and with less warning.

Reimagining International Payments

The RBI's research on local currency settlement reveals India's approach to reducing dependence on the dollar in international trade.

The traditional system is straightforward: most international trade happens in dollars. Indian companies export goods, get paid in dollars, and convert it to rupees. But this system has real costs – transaction fees, currency conversion risks, and dependence on dollar availability.

And so, the RBI has been exploring ways for Indian companies to trade directly in local currencies with key trading partners. They've set up frameworks with the central banks of UAE, Indonesia, Maldives, and Mauritius that allow businesses to trade without going through dollars. This system lets traders bill and pay for goods in their own currencies, cutting out the currency conversion step entirely. Instead of a Mumbai trader and Dubai buyer both dealing with dollar conversions, they can settle directly in rupees and dirhams.

RBI’s research shows that this approach can cut transaction costs, speed up settlements, and help develop currency exchange markets between trading partners. Over time, it can strengthen economic ties and lead to more cross-border investment.

But that isn’t the real point. The strategic value of this move becomes clear when you think about crisis management. In an increasingly fragmented world, having alternatives to the dollar-dominated system helps protect trade from global disruptions. If traditional payment channels face problems, countries with local currency arrangements can keep trading. That is, the RBI’s thinking about building resilience, for a worst case scenario. The RBI sees local currency settlement as a complement to the global dollar system, providing backup options that improve overall trade stability.

If more countries keep exploring similar arrangements, we could be seeing the early stages of a more diversified global payments system that's less vulnerable to disruptions in any single currency or country.

The Bigger Picture

Together, these research nuggets show an economy in transition. India's household savings are hitting record levels – the RBI data shows they reached ₹22 lakh crore or 6.5% of GDP. That's substantial domestic capital looking for productive opportunities.

The challenge is using this capital effectively. That’s what the RBI seems to be thinking about. The R&D research shows how we can convert research spending into actual productivity gains. The credit research reveals our financial system is becoming more sophisticated, with companies using cleverer funding sources. The FDI analysis shows Indian businesses are getting smarter about global expansion. The reserve management research indicates we're building defenses against political and economic shocks. The payments research shows we're developing alternatives to dollar dependence.

These are all connected pieces of India's evolution into a more complex economy.

Climate Change I: Why India must invest in resilience

There’s no sugar-coating it: we’re heading into a world where we will see serious climate problems. This isn’t something we really have a choice over: much like our grandparents didn’t have a choice in whether they would see the television, the computer or the smartphone make the world around them feel unrecognisable. People might disagree on how bad things get, but there’s no running away from the fact that they will get worse before they’re better.

This is especially true of our part of the world. South Asia is one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable regions — not just in terms of heat or floods coming our way, but in how exposed our economic systems are to both. We have dense populations which are rapidly urbanising, our water systems have always been stressed, and most of our population is in the fragile agricultural industry. There are few places in the world where the challenges to come will be as acute. And worse still, we don’t yet have the institutions, infrastructure or financial systems to mount a response.

Now, we’re not trying to depress you. These are the cards we’ve been dealt; we can’t wish them away. But we can understand what we’re in for, and how we can make our way through it. That’s why we’re looking at a recent World Bank report, titled From Risk to Resilience — which sizes up the challenge before us, and what we can do to get around it.

Today, we’ll look at how the World Bank sizes up the problem that our part of the world faces. In a coming episode, we’ll talk about the options we have ahead of us.

South Asia is in for serious trouble

We live in what is, perhaps, ‘ground zero’ for the global climate crisis. Since 2010, natural disasters have affected an average of 67 million people per year in South Asia, more than in any other region. You’ve probably lived through some of these events already, even if you personally had the resources to tide over them.

Ours is one of the hottest parts of the world. Already, on most days, we see highs of over 30°C — about 6°C higher than the average emerging market. If global heat levels rise, we’ll take some of the worst hits. By 2030, an astonishing 89% of South Asia’s 2 billion people are expected to face extreme heat risk. And we’re already getting there. In 2021, outdoor work in our part of the world was already unsafe for an average of six hours a day. By 2050, that will rise to seven or eight hours.

We’re also seeing an ever-larger number of floods. Between 2000 and 2018, nearly 40% of the region’s land area saw some flooding. By 2030, nearly half a billion South Asians are likely to face floods deeper than 15 cm.

If you’re trying to understand what the future brings, you should count all this into your economic baseline. Climate damage could shave off nearly 7% of South Asia’s economic output by 2050. The rest of the world will lose half that amount. South Asia’s industrial backbone is particularly vulnerable to weather shocks. Many of the region’s economic growth corridors — from Tamil Nadu’s manufacturing belt to Bangladesh’s port cities — are in flood-prone or coastal zones.

What makes things worse is that we’re poorly equipped to fight back. Governments in our corner of the world are under severe debt, and public resources are stretched thin. This leaves the heavy lifting to households and businesses — most of whom are already adapting, but only in basic, low-cost ways.

Climate change as an economic puzzle

The question of “how we’ll deal with climate change” is really an infinite number of questions. It is simultaneously a puzzle of physics, and engineering, and biology, and political science, and law, and mass communications, and every other domain of knowledge that exists. We’ll have to solve as many puzzles as we can if we want a chance at making it through intact.

One of those is an economic puzzle. It’s important to understand the economic dimensions of what’s coming our way, so that we can minimise that damage to whatever extent we can.

The firms

Four-fifths of South Asia’s economy is made by firms — businesses in the industry and services sectors.

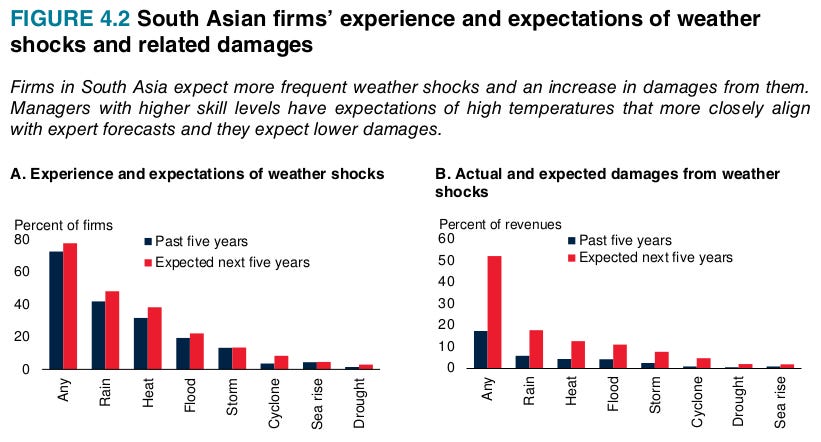

For all these firms, climate change may move from a background risk to a problem of day-to-day operations. In a World Bank survey, three-quarters of firms say that weather shocks hurt them in the last five years. They now expect that those shocks could wipe away as much as 52% of annual revenues between 2025-29, thrice the hit they took in the last five years.

This need not be something dramatic — they’ll face all sorts of problems. Sometimes, it’ll just be that retail stores suffer because it’s too hot to step out, or because the smog is particularly bad. It could be that companies have to rely heavily on night shifts, for which they have to pay more. But there’ll also be real tragedies, like a single flash flood that destroys a few months’ work. What specific risks you face will depend on where you are. But there’s a good chance you see some sort of problem.

Consider the 2015 Chennai floods. In that single event, Hyundai's export lots were inundated, the port went offline, and insurers raised container cargo premiums across the southern region by 15%. Meanwhile, local logistics firms faced weeks of revenue shortfall — and several SMEs downstream in the auto and textile supply chain reported production losses that quarter. This is kind of thing you should expect to happen more and more often.

But here’s the thing — businesses can protect themselves against some of these problems, at least, and some of them definitely do. Even the mere fact of having a decent management can help. Firms with skilled managers and better management systems shed 2-3 percent less revenue per year to climate-related shocks. Firms are usually pretty smart about anticipating what the weather could look like in the coming years. And this seems like something that can be learnt — because everything from having a more educated or experienced management, to having better skilled workers makes you better at preparing yourself for shocks.

Now, here’s the puzzle.

The stakes for South Asian firms are sky-high. If climate change can drag down nearly half your revenue potential, there’s a clear case for figuring out what you can do about it.

There are things firms can do to get ahead of these problems. Some of it is fairly simple, like having protocols and contingency plans in place, or making small building adjustments. The evidence suggests most firms are doing something to adapt to their changing reality, they’re just extremely slow and reactive. The average firm spends just 3% of their revenue on climate adaptations, even though the stakes are many multiples that amount.

So, why aren’t firms doing better? What can they do better?

The households

Of course, there’s little that businesses can do if the very people they sell to are distressed.

For South Asia’s 400 million-plus households, the climate threat will slowly but relentlessly keep draining into monthly budgets. As the climate change gets worse, the sub-continent will see some of the worst of what is to come. It’ll be significantly hotter than most other parts of the world. By 2030, 1.8 billion people — 89 % of South Asia — will swelter through extreme-heat days. At the same time, we will also be exceptionally vulnerable to floods. 462 million will also see once-in-a-century floods.

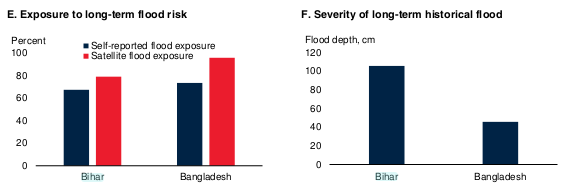

We’re already starting to see the damage. A World Bank survey in some parts of coastal Bangladesh and Bihar found that the average family had endured three different weather shocks in just the last five years. Some are hit worse than others — the urban poor, for instance, live in the sub-continents hottest areas.

Events like this throw households into complete disarray. For a relatively small number of people, weather shocks can injure or kill people altogether. But even if people aren’t hurt physically, they can run into severe issues. For instance, water and sanitation systems often break down during weather shocks — and people that have experienced them have a 45% chance of falling sick. Children’s education can be disrupted too, causing long-term problems.

Such shocks often hurt people’s wallets as well. Their houses and assets are damaged. Sometimes, things are so bad that people have to move altogether — in World Bank’s survey in Bihar and Bangladesh, for instance, 15% of all the families they spoke to had to migrate because of the weather shocks they faced. In the same survey, almost half of all people reported losing their earnings. Weather events are terrible for agriculture as well — a few days of bad weather can completely wreck a farmer’s livelihood.

But there are many things that we can do to reduce these risks. Something as simple as early-warning systems, for instance, can go a long way in blunt the blow of a weather shock. Nearly 90 % of households that are warned about a coming shock act to protect themselves, and can blunt their impact. And yet, most households don’t have access to early warnings. Less than half of all people receive flood alerts. Barely one-fifth hear about heatwaves or droughts.

Meanwhile, even more is possible if people actually plan for the long term. Even something as simple as making home improvements or purchasing insurance could go a long way in protecting people from the worst of weather shocks.

So here’s the puzzle.

Even though preparation can go a long way, most households aren’t doing nearly enough to prepare. A full 80% of households in the World Bank’s survey said they had made some changes to adapt to the weather. But almost all of those changes were extremely low-tech and incremental: reinforcing houses, harvesting rainwater, or cutting expenses. Just 1% had any kind of weather insurance. People barely turn to flood-tolerant crops or climate-resilient tools. Despite facing repeated shocks, most people don’t migrate or shift jobs. And when they do adapt, it’s usually reactive — driven by a recent experience of a flood or a storm, rather than by any real sense of what lies ahead.

So why don’t people do more? And what can we do to make households’ adaptation easier, cheaper, and more forward-looking?

Investing in resilience

Our baseline isn’t something we can choose. South Asia will take a hard hit from rising temperatures. But we do get to choose how badly it hurts us — and whether we’re able to cope, adapt, and move forward. That’s why the World Bank underscores the importance of investing in adaptation.

It’s not like we have a choice. If we do nothing, rising temperatures alone — without even counting extreme events like floods or storms — could cut our output and per capita income by 7% by 2050. And that’s if we don’t run into other nasty surprises.

A lot of options are closed to us. Governments in our region are perennially strapped for cash. But that doesn’t extinguish all our options. We can go a long way if people simply shift their resources to where they’ll be safer and more productive.

A lot of the damage to come could be mitigated if, for instance, workers move to safer places, or if businesses reorient towards more resilient sectors, or if enough capital can flow into softening the blow. The World Bank estimates that such market-led adjustments, called “autonomous adaptation,” could reduce climate damage in South Asia one-third.

Those are tremendous stakes — and getting there is an economic puzzle. We’ll need better infrastructure, wider access to finance, more transparent markets, stronger social safety nets, and investment in transport and connectivity. These aren’t climate policies in the traditional sense — but they are climate adaptation policies all the same. They allow economies to respond and adjust, rather than freeze up when the heat hits.

Even more is possible with targeted investments. Even small amounts of directed public spending — particularly in sectors like agriculture — could yield big returns. South Asia’s agriculture sector is unusually large, and unusually vulnerable. If governments were to invest just 0.1% of GDP per year in weather-resilient crops and farming practices — a little over a billion dollars a year for the entire region — it could shave off over a tenth of the remaining climate damage by 2050. That’s a sixfold return, even if only one in ten farmers ends up adopting the new technologies.

In a region where fiscal space is tight, and institutional capacity varies, we don’t have the luxury of solving climate change by throwing money at it. But we can go far just by helping people help themselves.

How do we do that? Does the World Bank have any ideas on where the answers might lie? We’ll get back to this in a coming episode.

Tidbits

Coal Power Dips as Renewables Surge: India’s May Power Mix Shifts Significantly

Source: Reuters

India’s coal-fired power generation fell by 9.5% year-on-year in May 2025 to 113.3 billion kWh, marking the sharpest decline since June 2020. Total electricity generation dropped 5.3% to 160.4 billion kWh, with peak power demand down 8% at 231 GW due to milder temperatures. Renewable energy output hit a record high of 24.7 billion kWh, rising 17.2% from the previous year and pushing its share in the overall power mix to 15.4%, the highest since records began in 2018. Hydropower generation also grew 8.3% to 14.5 billion kWh, increasing its share to 9% from 7.9% in May 2024. Natural gas-based power output saw a steep 46.5% decline to 2.78 billion kWh, the largest drop since October 2022. As a result, the share of coal in India’s power mix fell to 70.7%, down from 74% a year earlier, the lowest since June 2022.

BEL Secures ₹537 Crore in New Defence Orders, Strengthening FY25 Momentum

Source: Business Line

Bharat Electronics Ltd (BEL) has announced fresh orders worth ₹537 crore for a range of systems including communication equipment, jammers, simulator upgrades, software, and spares. This follows an earlier contract in May with the Indian Army Air Defence for the Integrated Drone Detection and Interdiction System (IDDIS), as part of a separate ₹572 crore order bundle. As of April 1, 2025, BEL’s total order book stood at ₹71,650 crore. In Q4 FY25, the company reported a net profit of ₹2,127 crore, while revenue from operations rose to ₹9,149.59 crore.

Vedanta Scales Up Renewable Power to 1 GW, Targets 2.5 GW by 2030

Source: Business Line

Vedanta Ltd has announced that it has achieved a renewable energy capacity of 1.03 gigawatts (GW) through signed power delivery agreements, with plans to increase this to 2.5 GW by 2030. The company's current portfolio includes wind, solar, and pump storage technologies, and is estimated to offset over 6 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions annually. Vedanta has stated that this reduction is equivalent to the carbon absorption of approximately 350 million trees each year. This move aligns with its broader commitment to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 or earlier. The company has not disclosed the capital expenditure or project-wise breakdown of the 2.5 GW roadmap but emphasized the strategic role of green energy in supporting its operational footprint across metals, oil & gas, and power.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Bhuvan and Pranav.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

An informative piece

Informative brief! Thank you