Can Shadowfax deliver?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Shadowfax’s Unusual Journey

Taming the tiger: How India is unwinding the Mauritius route

Shadowfax’s Unusual Journey

Shadowfax is, like so many others, a company that handles deliveries. As it joins its peers on the public markets, shortly, we have to ask: is it just one more third-party logistics player riding India’s big e-commerce wave?

Or is it built different?

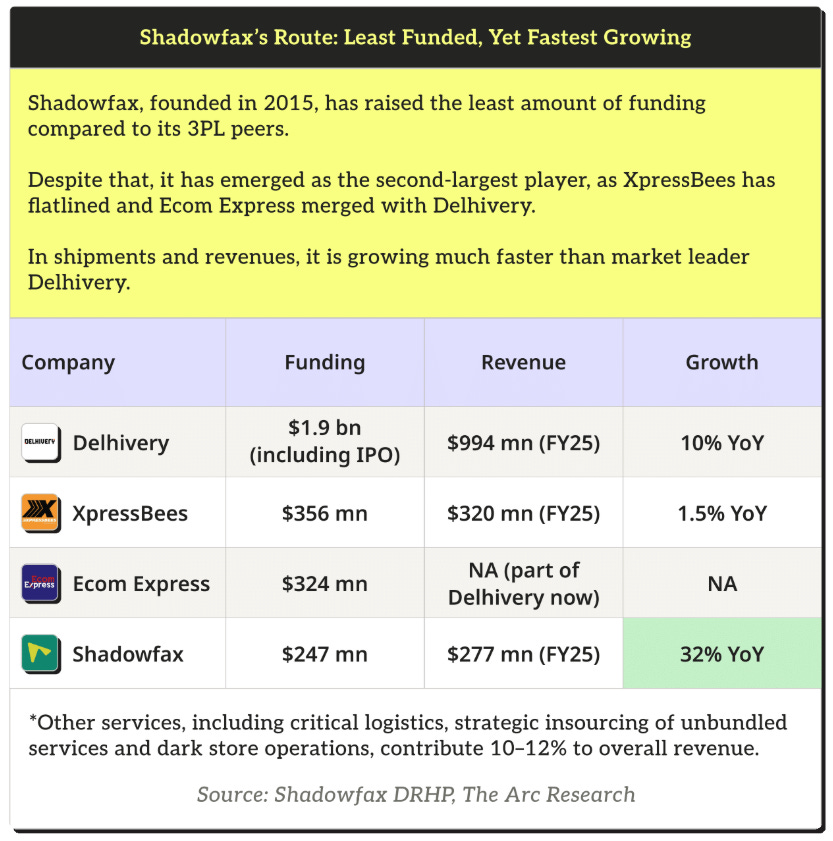

Consider this: since its 2015 inception, Shadowfax raised less than $250 million in funding — far less than rivals like Delhivery, which raised over $1 billion pre-IPO. Yet, Shadowfax became profitable relatively early, in FY2025.

Or this: there was a point when e-commerce giant Meesho dialed down its express shipping business, leaving the industry in shock. The move at least partially forced Ecom Express’ distress sale to Delhivery. Yet, Shadowfax managed to survive.

What’s going on? Is this a structurally unique company? Or is it just a typical one, with a streak of good luck? Shadowfax’s IPO gave us a chance to seek answers to this question. Here’s what we found — and will deliver (pun intended, hehe) to you in plain English.

What’s in a business?

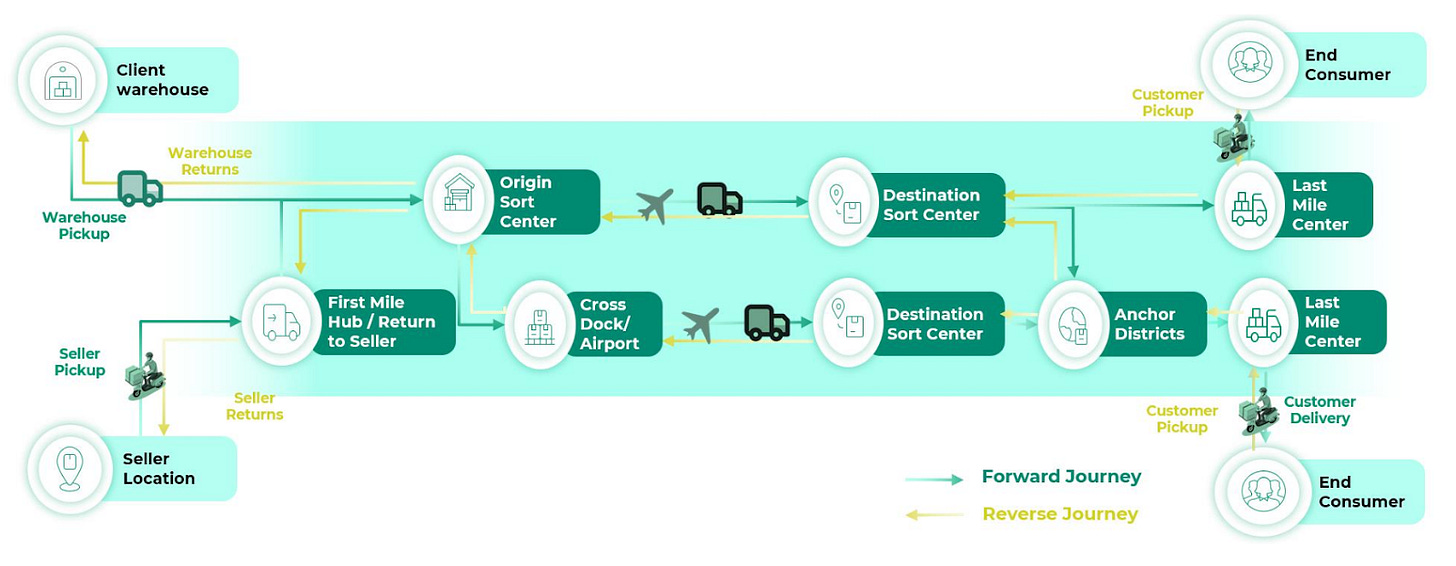

Shadowfax is a third-party logistics (3PL) company that handles last-mile deliveries. It essentially comes in at the very end, moving parcels from businesses to consumers — and sometimes taking them back.

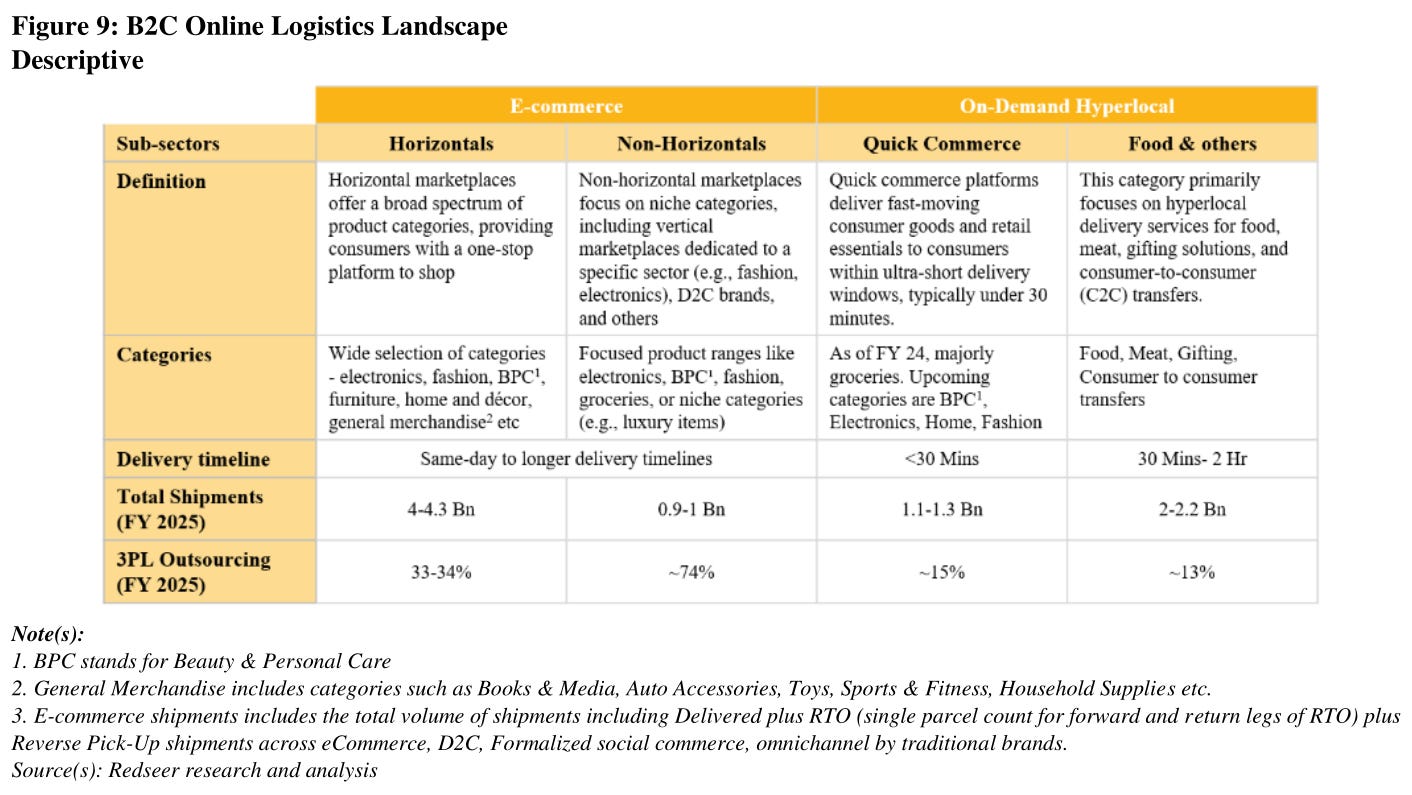

It’s part of an industry that currently splits into two end-uses: e-commerce, and on-demand hyperlocal.

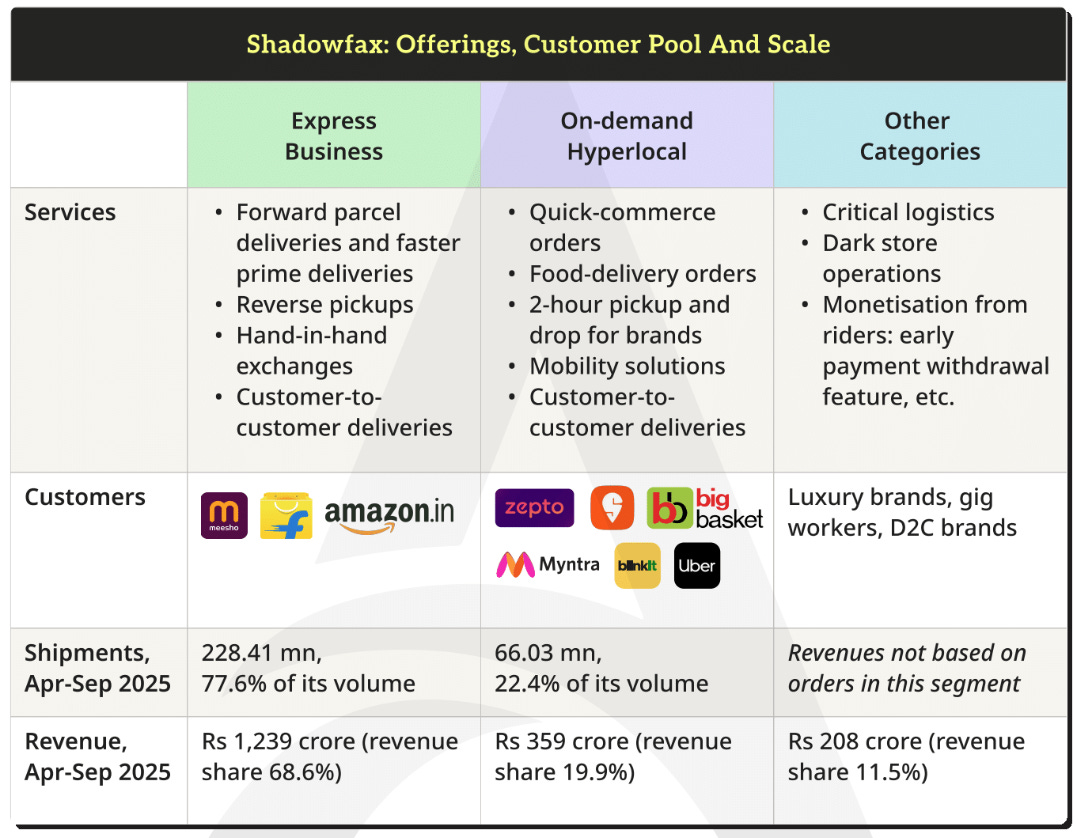

The first, e-commerce, is standard parcel delivery — picking up packages from warehouses and taking them to customers, usually within 1–3 days. ~70% of Shadowfax’s revenue comes from this business-line, where it handles everything from routine deliveries to returns. It serves major online shopping platforms, like Meesho and Flipkart, as well as direct-to-consumer brands.

Hyperlocal, another 20% of its business, involves quick, intracity deliveries. Think food deliveries, groceries, and “quick commerce” — the sort of deliveries made in minutes or hours, using two-wheelers. Shadowfax uses a large gig-driven rider network for this, working with food delivery apps, quick commerce players, pharmacies, and more.

You might wonder why they’re necessary at all. After all, don’t these platforms have their own fleets? They do, but Shadowfax comes in when orders slip between the cracks. About ~15% of quick commerce orders are outsourced to 3PLs like Shadowfax — when they need “overflow capacity”. Shadowfax claims it’s the only scaled 3PL player serving e-commerce, quick commerce, and food delivery at the same time.

The remaining ~10% of Shadowfax’s revenue comes from more niche offerings, like critical logistics, where clients need high-value or time-sensitive transport, running dark store operations for clients, and other odd jobs, like providing two-wheeler capacity to mobility or ride-hailing platforms.

The company’s operations are “asset-light.” It doesn’t own warehouses or vehicles at scale. Instead, it leases facilities and relies on crowdsourced delivery partners — gig workers using their own bikes — for most last-mile routes.

That flexibility is the heart of their business. But it also means tighter margins. Gig payouts and lease costs can add up. To keep the machine running smoothly, you need technology.

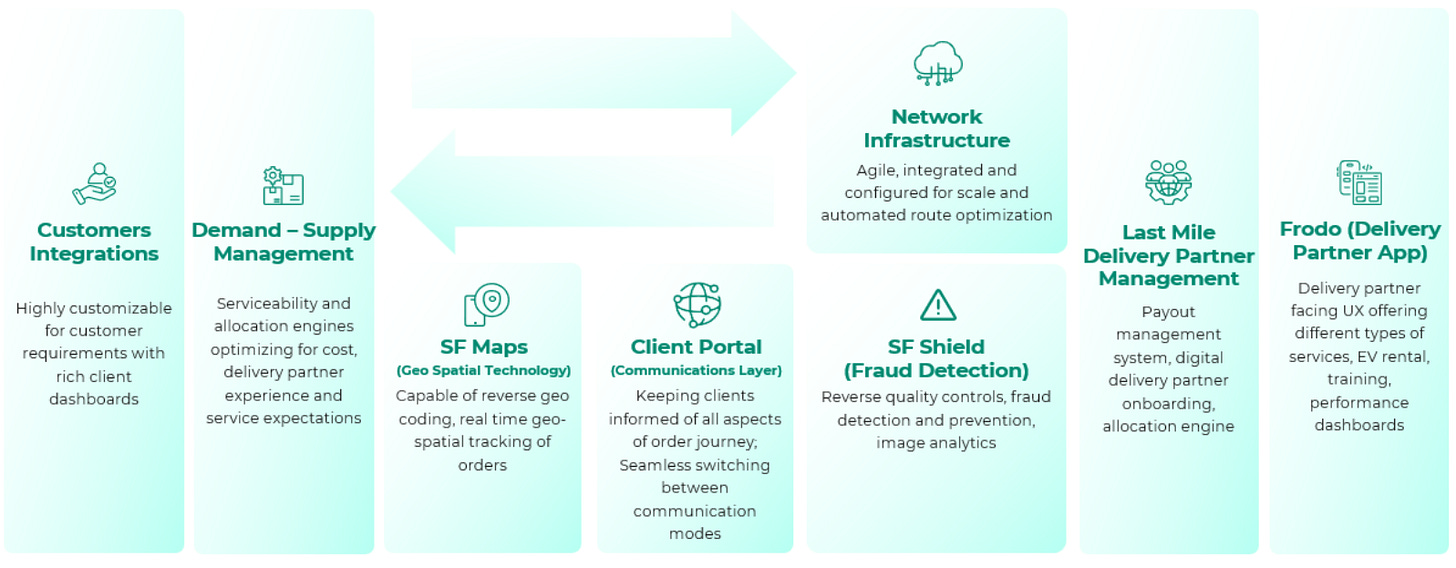

This brings us to its “Logistics OS.”

Inside the “Logistics OS”

Shadowfax likes to tout what it calls its proprietary logistics operating system. That’s essentially a fancy term for a bunch of software, processes, and people that together run the whole business.

First, there’s its physical infrastructure. As of September 2025, Shadowfax operates about 3.5 million square feet of logistics space. This includes first-mile centers (where sellers hand over parcels), large sortation hubs that route packages between cities, and numerous last-mile delivery centers near customer locales. All these facilities are leased. That keeps capital expenditure low, but requires constant lease renewals and rent negotiations.

The IPO funds will help secure more of these centers.

Then, like most new-age companies, they use technology heavily to smoothen their operations. Their backbone is an order management system which tracks every package across the network. This is plugged into in-house platforms to monitor shipments and workforce. Layered on top is a Track and Trace system — a CCTV and computer vision network at logistics hubs, which records each parcel handoff. Every time a package is scanned or moved, high-definition cameras capture it, and an AI engine verifies that the right delivery partner is handling it and putting it in the correct bin. This level of monitoring, along with geo-tagging and doorstep photos, help prevent theft or misrouting. Then, they have in-house tools to manage thousands of gig workers — with everything from fraud detection to AI-based identity verification.

Shadowfax often refers to all this as its “trust and efficiency stack.” The payoff is that despite handling delicate steps like cash collection and returns at huge scale, the system largely holds together. Of course, cracks still show up. There’s an occasional lost package, or cash pilferage. But the company’s selling point is that its logistics OS can deliver Amazon-like scale and reliability to any business that plugs in.

Where’s the money?

Despite razor-thin margins, Shadowfax has seen impressive growth. In the two years leading up to its IPO, Shadowfax nearly doubled its revenue — from ₹1,415 crore in FY 2023 to ₹2,485 crore in FY 2025. That’s ~33% CAGR. That momentum hasn’t stalled either. Its revenue for the first half of FY26 jumped 68% from the same period last year.

Those revenues reflect an explosion in shipment volumes. Across the industry, the average order value for online shipments have been going down. High value electronic and phone deliveries are now being overshadowed by smaller deliveries — beauty, personal care, fashion, grocery — which have lower ticket sizes. In turn, Shadowfax, and its peers, see lesser and lesser margins per order delivered. But Shadowfax appears to have made up by simply taking far more orders.

But that scale of orders doesn’t neatly translate into earnings.

Shadowfax’s seer scale has made it profitable — but only just so. The company was in the red through FY2024. It scraped into the black in FY2025 with a small ₹6.4 crore net profit. But its unit economics have been brutal. In FY 2025, for instance, Shadowfax’s profit per order was roughly just 15 paise.

Its operating margins are marginally better. In the first half of this year, it reported an Adjusted EBITDA margin of 2.86%. Despite bringing in ₹1,805 crore in revenues, barely ₹51.6 was reflected in its EBITDA. Roughly speaking, it was earning ₹1.75 per delivery.

That is its challenge. While the company is no longer burning cash, it isn’t minting much either. In comparison, Blue Dart — a more premium player — runs at ~15% EBITDA margin. Delhivery runs at around 4–5%. Shadowfax’s asset-light model, based on gig labor and leased sites, might give it a competitive edge, but it limits how much margin it can squeeze out.

When your margins are this thin, mistakes can be costly.

There’s a single cost-line that hurts the company deeply — “lost shipments”. Whenever packages go missing or get damaged, Shadowfax has to compensate clients. These leakages can hurt.

In FY2025, lost shipments cost it ₹141.0 crore, or almost 6% of revenue. But in the first six months of FY2026, that number jumped to ₹148.2 crore — or over 8% of revenue. That is, the amount Shadowfax spent covering lost/damaged shipments was seven times what it made in net profit.

Its management blames these losses on its heavy e-commerce volumes — and especially reverse logistics, which are messy. It claims to have built security systems to curb this. But will they work? If you plan to invest in them, look at this one thing carefully.

One (or Two) Clients to Rule Them All?

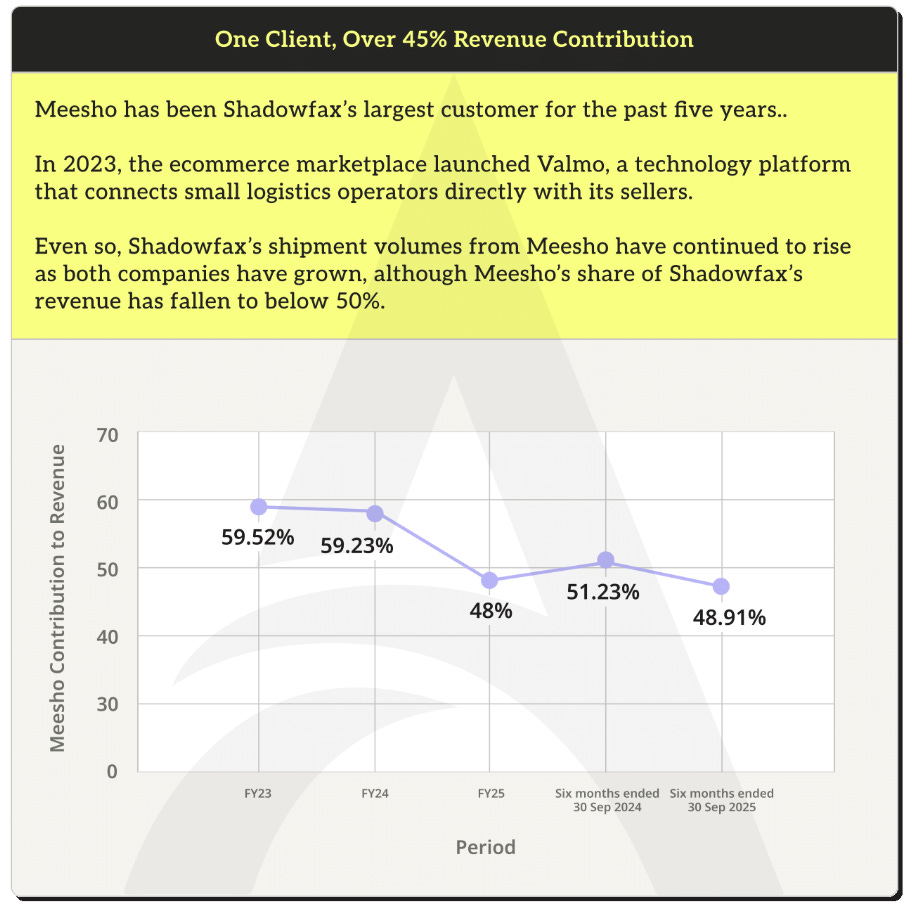

There’s one towering risk that Shadowfax has to live with: client concentration. Meesho alone contributed ~49% of Shadowfax’s revenue in H1 FY2026. If that single relationship goes sour, the company suddenly brings in half as much money.

This is a double-edged sword.

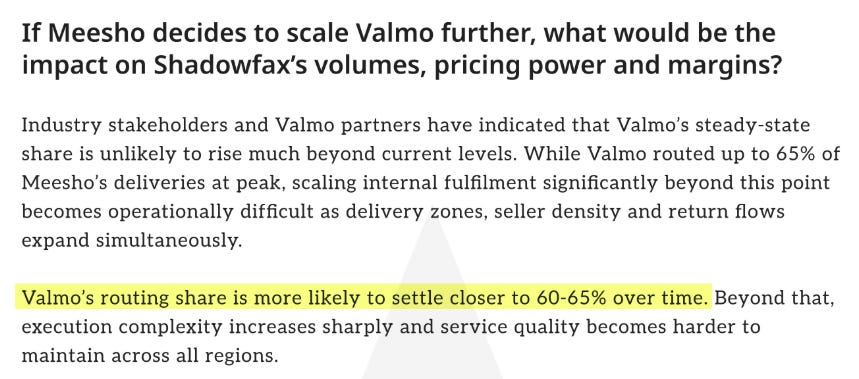

Meesho’s rise has been a huge tailwind for Shadowfax’s volumes and scale. But Meesho has also built its own logistics arm (ValMO). The competition wrecked others in the past. Ecom Express was once heavily dependent on Meesho. When Meesho moved those volumes in-house, the company collapsed. Could this happen again?

Maybe not immediately. TheArc thinks Meesho is operating close to capacity, and pushing much further could become “operationally difficult”.

But even if that’s true, Shadowfax needs to watch its back. Meesho doesn’t have to go “fully in-house” to hurt Shadowfax. Even a partial reallocation can carve into Shadowfax’s thin margins.

Flipkart is the other whale on its books. It’s a top customer, and a strategic investor. It, too, has its own logistics arm — Ekart — but Shadowfax typically steps in as an overflow / flexibility partner. That’s useful… but not comforting. An “overflow partner” is not the same as “core partner.” Overflow can disappear the moment the client expands capacity or finds a cheaper alternative.

This is what Shadowfax’s nightmares are probably made of. If Meesho or Flipkart stop outsourcing deliveries to Shadowfax, the company will have to replace tens of millions of orders quickly. And there aren’t many clients in India that can substitute those volumes. Until its client mix broadens meaningfully, Shadowfax looks somewhat like a high-quality vendor built around others’ strategies.

So, what’s the verdict?

Shadowfax, like so many others, is a 3PL company doing an unglamorous job: moving parcels, meeting SLAs, and trying not to lose stuff. But it is doing a few things differently. That’s why it has made money where others have failed. It’s how it stayed afloat when Meesho’s in-house operations broke others. It has managed to a reputation for execution in “specialised” lanes like reverse logistics and quick commerce..

That gives it credibility in the messy world of last mile logistics, with returns, cash-on-delivery dramas, doorstep checks, and unpredictable demand spikes. The company is somehow solving a brutal, low-margin problem. That alone makes Shadowfax a business worth tracking, to see if it delivers (yeah, we did it again).

Taming the tiger: How India is unwinding the Mauritius route

Consider an international transaction: there were three Mauritian entities, which sold shares they held in a Singaporean company to a buyer from Luxembourg. Seems like India has nothing to do with this, right?

Now, consider this one: in 2018, the American fund Tiger Global cashed out of Flipkart — India’s homegrown e-commerce champion, which was built in namma Bengaluru, serves Indian customers, and employs tens of thousands of Indians. This one has everything to do with India.

Only, they’re both the same transaction. While none of the parties involved had much to do with India, it was a fundamentally Indian business that changed hands. So is this an Indian transaction, or a global one? What matters more: the legal structure or the economic reality?

This is a question the Indian Supreme Court answered last week. The stakes were enormous. Tiger Global had been paid roughly $2 billion for its stake. If the transaction was Indian, the Indian government would get to tax it. Adding interest and penalties, it was asking for ₹14,500 crore in dues — close to what Tiger Global made in the first place.

The court ultimately sided with India’s tax authorities. Its ruling signals a shift in how India’s legal system treats foreign capital, marking an end to the era of “treaty shopping”.

Tiger’s big pay-day

Between 2011 and 2015, Tiger Global made a series of investments in Flipkart, via three entities set up in Mauritius. They looked Mauritian. They had offices in Mauritius. Each of their Boards of Directors were staffed by Mauritian residents. And they spent more than ₹3 crore in Mauritius between 2010 and 2018.

But they weren’t entirely Mauritian either. Between them, they just had two employees. Most of their actual work was carried out by an American company, Tiger Global Management LLC, which was their “investment manager” on paper.

On the other end, those entities didn’t buy a stake in Flipkart’s Indian operations either. Instead, they got parts of Flipkart Private Limited, Singapore — which, in turn, controlled the Indian business. And later, when Walmart came calling in 2018, shares of that Singaporean entity were sold to Fit Holdings S.A.R.L., a Luxembourg entity.

Why jump through all these hoops, though? Well, that takes us to how a tiny African island became the primary gateway for foreign money to enter India.

The Mauritius route

Back in 1982, socialist India was learning just how much capital we needed to grow, even though we had very little. We were realising that we needed foreign money, even though we lacked the credibility to actually draw any in. Mauritius, meanwhile, was positioning itself as a financial intermediary. Our governments shared a cordial relationship, and so, we decided to enter into a tax treaty.

The treaty, in essence, said that if entities from one country made capital gains in the other, their home country would have the right to tax them. On paper, this would avoid “double taxation” — that is, investors wouldn’t be taxed twice for any investments they sold.

Only, Mauritius didn’t levy capital gains tax at all. This created a loophole: if you invested in India via Mauritius, neither India nor Mauritius would tax your gains. You’d pay zero tax on exit!

This would stay under the radar for a decade. But then, two things made it a goldmine. One, India began its economic liberalisation, drawing in a flood of foreign investment. Two, Mauritius passed its ‘Offshore Business Activities Act’, creating a framework which let companies incorporate and “reside” in Mauritius, even if their actual business happened elsewhere. Together, this meant that investors from across the world could set up shop in Mauritius, on paper, before sending money to India.

This became enormously popular. FPIs, PE funds, and VC firms started routing their Indian investments through Mauritius structures. By the 2000s, Mauritius had become one of the largest sources of foreign direct investment into India

India knew what was happening. But we were also competing for foreign money, and this was a fantastic sweetener. In 2000, in fact, when some tax officers tried denying treaty benefits to foreign funds, the Central Board of Direct Taxes issued a circular explicitly blessing the route — confirming that a valid Tax Residency Certificate from Mauritius was enough for a tax exemption. The Indian Supreme Court itself blessed this approach in 2003, in the Azadi Bachao Andolan case.

India would even extend the same exemptions to Singapore, a few years hence.

Nothing lasts forever

By the 2010s, however, the calculus had shifted. Our economy was larger and more confident, while revenue leakages from “treaty shopping” were mounting. The world, at large, was souring on convoluted tax structures. Organisations like the OECD had launched programs to eliminate “tax avoidance”. It was time to close the Mauritius loophole.

In May 2016, India and Mauritius amended their tax treaty. From April 1, 2017, the capital gains exemption would end. India regained the right to tax any returns Mauritian investors made. This ruined the plans of investors who had already structured their investments through Mauritius, though, based on the old treaty. And we still wanted investors to think we were a stable place on which to bet their money. So, as a compromise, the old exemption was “grandfathered” for investments made before April 2017. It would only apply to investments which came in after that date.

But India went further — in 2017, it also introduced the General Anti-Avoidance Rules (grandfathered). The rules allowed tax authorities to deny tax benefits from an arrangement if its only purpose, it seemed, was to get that tax advantage. Importantly, these rules would override any tax treaty. From that point, even if an international treaty created a tax exemption, you could not rely on it blindly. India would check if you actually had business there.

Tiger Global had made its investments well before the April 2017 cutoff. But they exited in 2018, after the GAAR had kicked in. That set up a clash: did the Mauritius treaty’s grandfathering provisions protect them, or would they get caught under GAAR’s net?

The case

Before closing the Flipkart sale, Tiger Global approached Indian tax authorities. They wanted a confirmation, in advance, that they didn’t have to pay tax. That request was rejected. The authorities refused to accept that this was a Mauritian investment; they claimed that those Mauritius entities were controlled from elsewhere, and couldn’t make independent investment decisions. Instead, they asked that between 6.05% and 8.47% of Tiger’s investment returns were to be “withheld”.

Tiger escalated the matter. First, they went to the Authority for Advance Rulings (AAR) — but the AAR refused to side with them. So, they appealed to the Delhi High Court.

The High Court was sympathetic to Tiger Global’s case. It reversed the AAR’s decisions, holding that it was still protected by the Mauritius treaty, and its income wasn’t taxable in India. This is when things reached the Supreme Court.

Tax evasion and avoidance

Here’s what the law wants to do.

Legally, you’re not allowed to “evade” tax. That is, you can’t hide your income, or fake your records, or defraud the government in some way. “Avoiding” tax, though, is a different matter. If you find a loophole within the law that lets you pay less tax, you’re within your rights to use it and bring down your liability. You can, for instance, set up tax-efficient investment vehicles, use deductions, or structure transactions to reduce exposure.

Tiger Global was avoiding tax, not evading it. They weren’t hiding transactions. They disclosed everything, filed proper documentation, obtained the necessary certificates, and went under a treaty.

Over the last couple of decades, though, countries across the world have been clamping down on the most aggressive forms of tax avoidance as well. That’s what GAAR, too, is trying to do. This doesn’t make all tax avoidance illegal. But if an arrangement’s main purpose is to avoid tax, and there’s little else to it, the tax benefit can be denied. With this shift, tax authorities can disallow an arrangement that is formally lawful.

The Mauritius treaty, taken by itself, created room for legitimate tax avoidance for investments made before April 2017. But the GAAR nullified this. If you were trying to claim a tax benefit once the GAAR kicked in, and the whole set-up was meant purely for that, you would have to pay tax.

The court’s logic

With that, let’s return to the Supreme Court, and the Flipkart sale.

The court basically found two issues with the transaction. One, it refused the idea that Flipkart was a Singaporean entity. If most of its value came from India, it didn’t matter if Singaporean shares were sold — the asset changing hands was Indian.

Two, it thought the Mauritian entities were so only by name. They lacked any real substance. The US-based Tiger Global Management LLC actually took all their decisions. In fact, the Mauritius arm wasn’t even allowed to sign off on transactions exceeding $250,000. It may have had a strong enough presence to get a residency certificate from Mauritius authorities — but that didn’t save it from GAAR.

In all, this wasn’t actually a case of a Mauritian entity selling Singaporean shares. It was an American entity that sold Indian assets. The court, in other words, sought substance over form.

To be clear, this isn’t the final decision in the matter — and it doesn’t automatically mean Tiger Global will have to pay out ₹14,500 crores. The Supreme Court is simply signing off on the broad idea that the fund won’t get treaty benefits, and will have to pay tax in India. What it’ll have to pay, however, will be decided in a separate set of proceedings.

But it does establish a core principle: that treaties can’t bring blanket immunity.

This was a break from its past. Back in 2003, in Azadi Bachao Andolan, the court had given its explicit blessing to the same treaty. Back then, it barred authorities from looking behind a tax residency certificate from Mauritius. Perhaps, in those days, attracting foreign investment mattered more than plugging tax leaks. But now, the context has changed, and so did the court’s position.

A fundamental tension

This brings us to a fundamental tension between two very different goals: should we be more focused on attracting foreign capital, or should we care more for protecting tax sovereignty? This is a genuine trade-off. Both choices have their costs.

For years, India chose investor-friendliness. The Mauritius route was tolerated, even encouraged, because capital was scarce and India needed to compete for it. That balance has now shifted. India is more willing to assert its rights over income from Indian assets, even if that makes us less attractive to some foreign investors. Treaty-based benefits, from this point, guarantee nothing.

But India still needs foreign investment. Right now, the Rupee is under serious pressure. One reason, as we’ve mentioned before, is a lack of demand from investors. This verdict could add to their uncertainty. If an investment that is protected by a treaty can still be challenged on its substance, any deal from the past — among the thousands of exits made through Mauritius or Singapore — could face scrutiny next. That could dampen investment appetite even further.

This doesn’t make our approach illegitimate. It does, however, put pressure on us to make ourselves attractive through non-tax means. If we aren’t handing out sops to investors, our fundamentals will have to shine that much more.

Tidbits

RBI has asked HDFC Bank and ICICI Bank to set aside ₹1,783 crore in additional provisions after its annual supervisory review found gaps in how the banks classified agricultural loans under priority sector lending norms. ICICI Bank bears the larger burden at ₹1,283 crore, while HDFC Bank must provision ₹500 crore. Both banks clarified this is a classification issue and not a sign of asset quality stress.

Source: Economic TimesCanada has signed a trade deal with China. The deal allows 49,000 Chinese EVs into Canada annually at just a 6.1% tariff — down from 100% — while China will cut canola tariffs from ~85% to 15%. Canadian PM Mark Carney called China a “more predictable” partner than the US in a “new world order” — a striking shift for a country that sends 70% of its exports south. Carney’s goal: double Canada’s non-US exports in a decade.

Source:BloombergReliance Retail says its quick commerce and FMCG businesses are now contribution margin positive — a rare feat in a sector notorious for burning cash. JioMart hit 1.6 million daily orders by end-December, up 53% quarter-on-quarter and 360% year-on-year, keeping Reliance on track to be the second-largest quick commerce player behind Blinkit. Quick commerce contributes about 20% of total retail revenue, up from 18% a year ago.

Source: Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Pranav.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Shadowfax currently operates in the delivery of simple consumer goods. however, relying on this sector and fewer client base poses a significant long-term concentration risk. We cannot simply assume that partners like Meesho or Flipkart willnot continue to expand indefinitely. Our primary objective should be utilizing capital to strengthen our business fundamentals. For instance, the pharmaceutical distribution channel remains underserved with few major players. While it requires significant investment, implementing cold-chain logistics and advanced supply chain technology would make Shadowfax more efficient and provide a sustainable competitive advantage in the long term.