Can boAt stay afloat?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Can boAt stay afloat?

What is the role of coal in India’s energy transition?

Can boAt stay afloat?

Back in 2022, India’s IPO market, after running hot for over a year, suddenly slammed shut. Many newly listed high-growth companies saw their share prices nosedive. Companies like Nykaa and Zomato corrected heavily, while PayTM saw its shares cash in a disastrous debut. The markets, it seemed, had soured on new-age stocks.

Back then, Imagine Marketing — the parent entity behind boAt — had been waiting in the wings. It had filed its draft papers for a ₹2,000 crore IPO in January, but increasingly, it seemed like the market simply wasn’t ready for another company with high growth but low margins. By October, the company had shelved its IPO plans.

Three years hence, the company is heading back to the markets, with a smaller issue of ₹1,500 crore. This time around, it’s twice as big, and both its supply chain and distribution channels look more resilient. Has it covered enough ground to warrant your investment, though? Well, for that, let’s dive in.

Understanding the business

BoAt is a giant of India’s consumer electronics industry.

The scale of its business is genuinely remarkable. It dominates India’s audio market — it has consistently been India’s largest audio brand, selling more than one-third of the country’s personal audio devices. Last year alone, it sold 34 million units, making it the world’s fourth largest personal audio player by volume. It is also relentless in chasing new products, pushing out over 100 SKUs every year.

Most of its business comes from the “mass premium” market — or what the company’s offer document terms “aspirational.” It essentially floods the market with a large number of good-looking, feature-rich products that are all sold at aggressive prices — usually under ₹5,000.

While there’s no denying boAt’s size, its strategy has two implications. One, there’s very little that differentiates boAt from its rivals, aside from their sheer scale. They’re competing in a segment that’s all but commoditised — companies like Boult, Noise and others are gunning for the same customers, and may not have much of a moat to keep them away. Two, the intensity of competition leaves the company with very little pricing power. Its margins are razor-thin.

Really, the biggest thing keeping boAt’s business afloat — its largest and most enduring moat — is brand recognition. In a sea of similarly priced alternatives promising the same capabilities, boAt’s key advantage is that people have heard of it. And so, one way of thinking about boAt’s business is that underneath its consumer technology engine, it’s really a marketing company.

To run such a business, boAt needs to make itself look attractive to young, trend-conscious users. For that, it has to spend heavily on marketing itself. That can take all sorts of forms — from running online communities, to running prime-time TV ads with celebrities like Ranveer Singh or KL Rahul. But the company has also thrown in the occasional guerilla marketing trick — helping it gain from the popularity of others. When Apple was marketing its airpods, for instance, the company launched its own series of in-ear speakers, which it called “Airdopes”. And that’s far from the only pot-shot it has taken at Apple:

The nuts and bolts of the business

Products

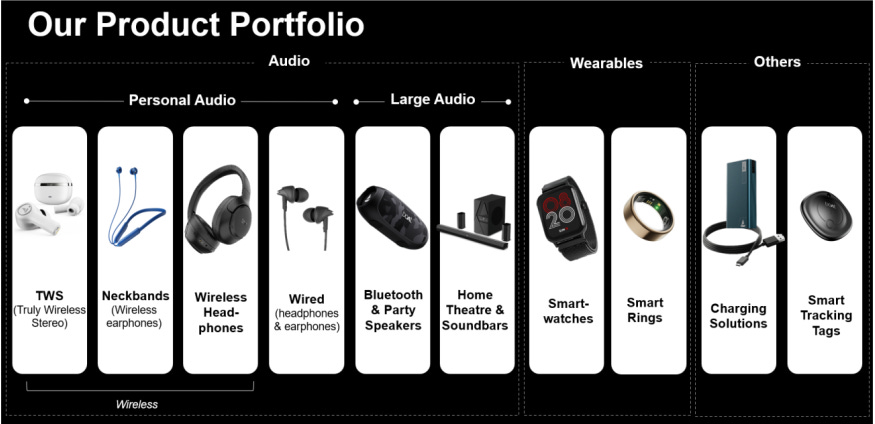

BoAt has three main categories. The heart of the company lies in audio: where it makes everything from headphones to home theatre systems. It also makes “wearables” — smartwatches and smart rings — as well as an assortment of other products, like chargers, power banks and smart trackers.

Audio is the category where boAt has made its biggest mark. It’s where most of the company’s revenues — as much as 84% in FY 2025 — come from. Most of this, however, is in “personal audio”, or products like headphones, neckbands and in-ear speakers. The segment seems past its initial, explosive growth phase, and is now settling down to a growth rate of barely 6-9% a year.

The more exciting segment, according to the company’s offer document, is large audio — bluetooth speakers, sound bars, home theatre systems, and the like. This market is growing almost twice as fast, at 12-16% a year. And while boAt has a real presence here — coming within India’s top 3 large audio players — it doesn’t dominate this market. That gives the business a little headroom to grow.

Some of the company’s other bets, however, look less buoyant.

Smartwatches, for instance, look like the company’s biggest problem segment. India simply doesn’t seem very keen on the market — in 2024, in fact, smartwatch shipments in India dropped by over 34%.

This is also a tricky segment to master. Over the years, people have come to change why they’re using smartwatches. These are no longer fashion products; they’ve become healthcare and utility products. Increasingly, the competition isn’t about how something looks, but around things like the range of sensors a watch has, their accuracy, or the developer ecosystem around it. This makes them a more complex category — which requires a lot of innovation and capital expenditure. The audio playbook need not work here.

This has been very bad news for boAt’s own business. In just the last two years, in fact, its wearables business fell by 63% — from over ₹900 crore to just ₹330 crore.

The chain

How does a boAt product come together?

Take audio. To simplify things massively, you can think of a speaker as a mix of three things.

First, there’s all the core pieces of technology that, if put together, act like a speaker: such as batteries, chips, bluetooth modules and the “drivers” that actually make sounds. These are complex technologies, but luckily, there are suppliers who make them in bulk. Second, you need to string all these together through a custom circuit board, so that they work in unison. Finally, you dress all of this in a nice-looking shell, making it look like a complete, finished product.

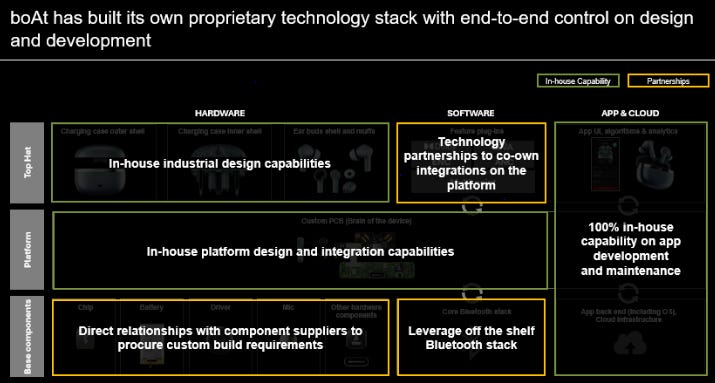

BoAt doesn’t own any of the core technology behind its speakers; all of that belongs to companies like Dolby or Qualcomm. The components themselves are usually put together by specialist suppliers in China or Taiwan. The same components are available to anyone in the business, including boAt’s rivals — although boAt might be able to tweak the specifications.

The company comes in at the next step. It runs “boAt labs” — a 100-member in-house engineering team that custom-design circuit boards, and the embedded software that binds those components together. The team also designs the outer shells that give its speakers their distinctive look. In that sense, boAt isn’t a technological innovator; it isn’t pushing at any engineering frontiers. Its role is to take that well-known, commodified technology, and combine it in a way that looks nice and works well.

Once those designs are in place, somebody needs to do the physical work of assembling its speakers.

World over, consumer electronics businesses send that work to Chinese contract manufacturers based in cities like Shenzhen. Not too long ago, this was boAt’s playbook as well. Its 2022 offer document indicated that “all or substantially all” of its manufacturers were in China.

Since then, though, it has flipped its strategy, moving most of its business to Indian manufacturers. By FY 2025, in fact, more than three of every four units it sold were manufactured in India — from less than 40% just two years ago. To be clear, much of that “manufacturing” is just the final assembly. Most of the underlying, hard-to-make components still come from abroad. But it’s a start. And importantly, it helps the company avoid paying import tariffs.

A single collaboration handles most of that work of assembly: Califonix, a 50-50 joint venture between boAt and Dixon Technologies. In FY 2025, this unit manufactured over 3 million units, or over 37% of everything it made in India. This unit also gives boAt control over its manufacturing process, and by extension, the quality of what it sells.

Distribution

Historically, boAt has always depended on e-commerce for practically all its sales. Two platforms — Amazon and Flipkart — brought the company a lion’s share of its business. These were convenient, and they gave the company a lot of visibility. But they also created an existential risk. Any change to their algorithms, payment terms, fee structures, or more could create serious problems for the company.

Over time, boAt is trying to break out of this problem.

For one, the company is slowly building out an offline presence, much like its more traditional peers. This is particularly important with slightly higher value products, like home theater systems, that customers might prefer sampling before they make a purchase. The company has been working with companies like Croma and Vijay Sales to place its products in their physical stores. Its network. This push has borne fruit; the company’s products are now placed in over 12,000 retail stores. And with that, nearly 30% of its sales have shifted off-line.

Even online, the company is diversifying its distribution channels. For one, it’s building out its own direct-to-consumer website. As you might have noticed for yourself, it has also scaled up its presence on quick commerce.

For all this, however, its dependence on e-commerce remains. In FY 2025, 55.3% of the company’s sales were just through its top two marketplaces.

Looking through the numbers

When boAt first approached the markets in 2022, it appeared to have hit steady profitability — even if its margins were small. But then, the picture began to sour. While the company was pushing up its overall revenue, it had started marking losses. Finally, however, it has managed to arrest that trend. After a loss of over ₹129 crore in FY 2023, and another of ₹80 crore in FY 2024, last year, the company dragged itself to a profit of ~₹61 crore.

The turnaround, however, came from the company optimising its revenue mix. Its overall sales, in fact, have declined slightly over the years — from ~₹3,380 crore in FY 2023 to ~₹3,100 crore last year. That is, although its margins may have improved, right now, it doesn’t really seem to be growing rapidly.

A major part of this story, it seems, was the company’s wearables business line. This was a business line that the company had bet big on. Back in 2022, for instance, it acquired the Singapore-based KaHa Technologies for its portfolio of wearable-based technologies. Only, over the last couple of years, the company found itself retreating from the segment to save its bottomline. Its wearables segment is now a third of what it was two years ago, and while that pushed down its revenue, it also rescued the company from losses.

But if not wearables, where does the company’s future lie? Audio devices are probably not it. In fact, it’s a segment where the company’s profit margins are slowly eroding. Over the last year alone, its audio segment margin fell from 9.30% to 6.63%. And yet, this segment is becoming more, and not less relevant to its finances.

The bottomline

BoAt is an incredibly strong brand in India’s consumer electronics space. The volume of its sales eclipse its competitors, and that alone sets it apart. But it’s going about this business the hard way. With few structural moats, and no proprietary technology to hide behind, it’s playing the hard game — competing purely on speed, cost and brand. To succeed, the company must consistently stay ahead. If a competitor comes close, customers could switch out overnight.

But is it enough for the company to even keep its market?

At the moment, boAt’s financials make it look like an old, maturing business rather than an exciting start-up. Its revenue has plateaued, and any improvements to its bottomline are coming from gains of a few basis points on the margin. It’s on the top of its biggest market, and yet, its dominance amounts to a mere ₹60 crore in profit. It isn’t obvious that this figure grows much larger.

To us, it looks like the company needs something to spark off a new phase of growth. Without that, this is simply the best business in a difficult, crowded category — a good position to be in, but not an enviable one.

What is the role of coal in India’s energy transition?

India’s energy mix is changing, and fast. Renewables are racing ahead, with solar leading the pack. Suddenly, India’s National Electricity Plan (NEP) 2032 solar target looks within reach. Wind, though slower, is picking up speed thanks to stronger policies and smarter auctions. Large hydro projects are on track to beat their modest targets. New technologies like battery storage, essential for making renewable energy reliable, is finally gathering momentum.

Coal, however, towers over everything else.

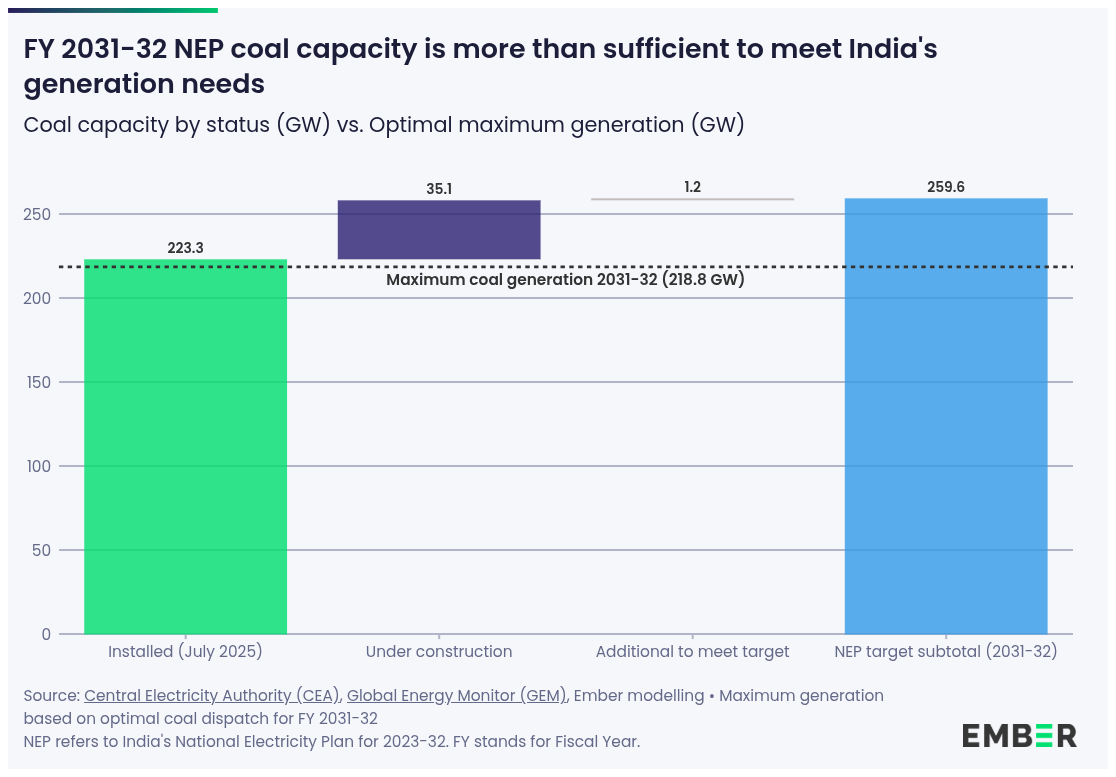

It’s India’s single largest source of power, with about 217 GW of operating capacity and another 35 GW under construction. Most of those plants were approved years ago. Once they’re completed, India will likely hit its NEP 2032 coal capacity target without fresh proposals.

Coal is at a turning point: it isn’t disappearing, but its era of aggressive expansion is over.

Coal has always been India’s energy workhorse. That foundation is now shifting. Its dominance is being challenged, and with that, its role is changing. What the country will soon expect from coal — and how it fits into an increasingly renewable grid — will look very different than it did. That’s what we’ll explore today, through a report from Ember energy.

Coal’s changing role in the grid

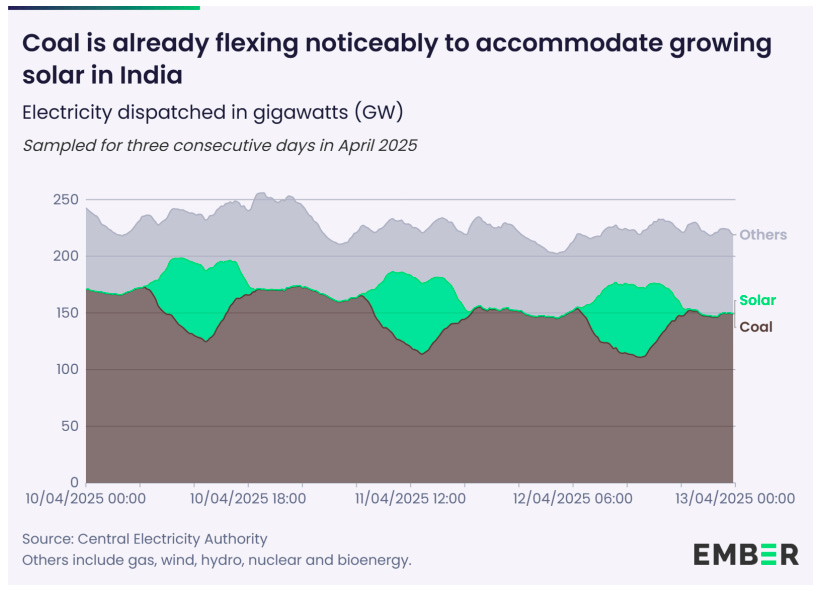

As India’s grid adds solar and wind, coal’s role is changing — from a steady, always-on power source to acting as a flexible backup. To this point, coal plants always ran at full output day and night. Now, they must ramp down at midday when solar power floods the grid, and ramp back up in the evening when the sun sets and demand spikes.

The problem is, coal plants aren’t built for such quick changes. These ignite tons of coal, which boils water into steam to spin turbines. This takes time to start, and when it begins, takes time to cool down. Meanwhile, sudden shifts in temperature can stress the metal parts, cause cracks, and reduce efficiency. So, operators have to move slowly. The physics of coal makes flexibility barely possible — but not easy.

Already, however, India’s coal plants are showing levels of flexibility once thought impossible. Take April 2025: solar alone supplied 60 GW at midday, and as sunlight peaked, coal plants had to slash their output by around 52 GW within six hours: an average ramp-down of 8.7 GW per hour, among the steepest ever recorded.

In reality, though, only a subset of newer, more advanced coal units is capable of this kind of maneuvering. Older plants are built for steady operation. They struggle to adjust quickly without damaging equipment or losing efficiency. So, while the system as a whole is becoming more nimble, that flexibility is coming from a small group of modern, better-maintained units carrying most of the load.

Meanwhile the need for flexibility will only intensify.

Ember’s analysis suggests that India’s coal plants will have to become far more flexible — but also much less utilized. By 2031–32, the average plant load factor (PLF) could fall to about 55%, down from roughly 69% in FY 2024–25. The typical coal plant will spend nearly half its time idle or running at minimum output, kicking in mainly during evening peaks or overcast days.

Essentially, India’s coal fleet is being split into three categories — “baseload” units that still run for many hours (the cheapest, most efficient plants), “flexible” units cycling on and off daily, and “peakers” that operate only at peak times.

This new role completely changes a coal plant’s operations and economics.

This shift has big technical and financial consequences. Coal plants must now ramp faster, run deeper turndowns (to around 40% of capacity or less), and handle frequent start-stop cycles. Most of India’s coal stations weren’t designed for this. It means new control systems, hardware tweaks, and revised operating procedures. It also means plants will often run below their optimal efficiency, burning more coal per unit of electricity when idling or operating at low loads.

However, studies show that with the right upgrades, coal plants can become flexible without huge extra costs. The Central Electricity Authority (CEA) found that operating coal plants flexibly would only raise costs by about 10–15%, compared to normal use for newer units.

Coal’s role is changing — from the main power source to a backup that keeps the grid stable when needed.

Why coal power is getting more expensive

As coal plants shift to their flexible role, the cost of coal-fired electricity is set to rise significantly.

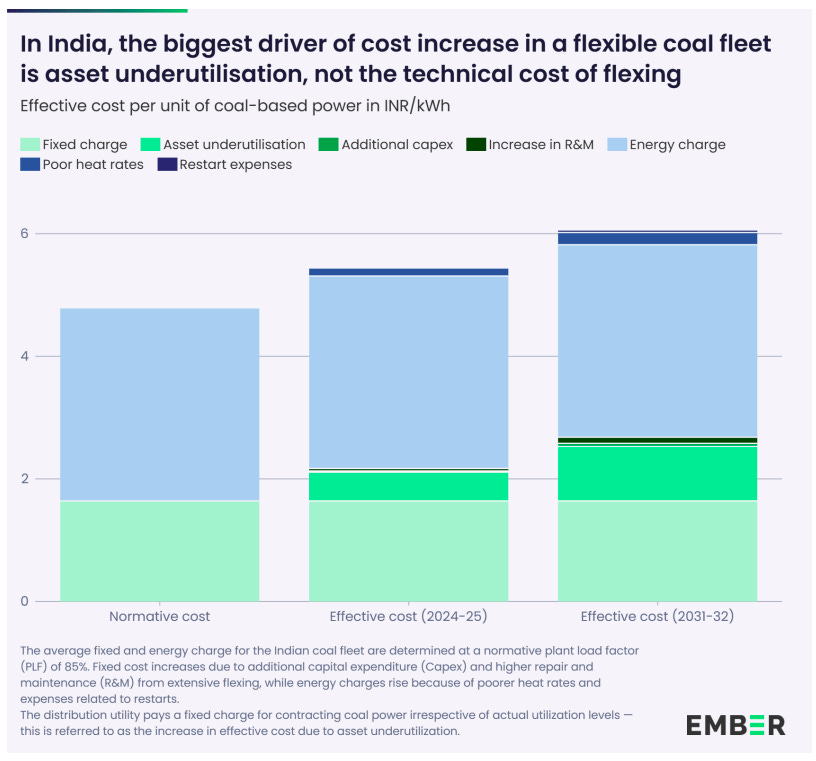

The economics of coal power include two main components: fixed costs — largely capital and financing costs — and variable costs — fuel and operations costs for each unit of energy. When a plant’s output (PLF) drops, the fixed costs are spread over fewer kilowatt-hours, causing the per-unit cost of electricity to jump.

Ember’s analysis finds that, today, the weighted-average cost of coal power — accounting for both fixed and variable charges — is about ₹4.8 per unit for the existing fleet. However, if the average coal PLF falls to ~55% (from ~69% now), the effective cost would rise to around ₹6.0 per unit. That is roughly a 25% increase in average tariff for coal power.

About 85% of this projected escalation comes from lower plant usage — the same fixed costs being split over fewer kWh — rather than technical inefficiencies.

That said, the variable cost, too, is expected to creep up as plants cycle and run at partial loads. When a coal unit is throttled down, its “station heat rate” — or fuel needed per unit of electricity — worsens. A plant operating at 55%, instead of the optimal 85%, PLF can raise heat rate by about 7–9%. That is, the plant must burn 7-9% more coal per kWh generated. This directly inflates the fuel cost (energy charge) for each unit of electricity.

The financial implications are stark. New renewables paired with storage are increasingly able to provide firm, dispatchable power -– the kind needed to reliably meet demand at all times — at competitive prices. Recent bids for “Firm and Dispatchable Renewable Energy” (FDRE) — a mix of solar or wind coupled with batteries or other storage — have yielded tariffs in the range of ₹4.3–5.8 per unit. Even solar-plus-battery projects designed for peak delivery have come in around ₹2.9–3.6 per unit. In contrast, a new coal plant today would likely need to charge nearly ₹6 per unit to recover costs under a typical 25-year contract.

This means coal power is already more expensive than firm renewables in many cases. The gap will only widen as coal PLFs decline. Put simply, thermal power is no longer the least-cost option for reliable power — not even close, given the advancements in clean energy economics.

So what now?

The Ember report lays out a playbook for how India can actually manage this transition. Its focus is twofold:

First, make coal more flexible.

India’s existing coal fleet wasn’t built for a renewables-heavy grid — most plants can’t safely run below 55% of their capacity. Ember suggests pushing that down to 40%, so coal can step in only when needed instead of running constantly. Regulators need to move fast — identifying units which can handle those lower loads, and create payment mechanisms so plants aren’t penalized for ramping up and down. Over time, all coal plants should be required to meet this 40% minimum-load standard.

Second, go big on storage.

As solar keeps booming, storage keeps the system balanced. Without enough of it, we’ll end up wasting clean energy during the day and still find ourselves burning coal in the evening. Ember’s message is this: India needs far more storage than currently planned. Storage, clearly, is core infrastructure, not just an add-on. Regulators must start valuing what batteries actually do — their flexibility and speed — so the business case for investment becomes obvious.

We need smarter operations, more flexible coal, and a massive scale-up in storage. Together, these steps form a roadmap for managing coal’s shrinking role without risking grid reliability. It’s also a roadmap for what to invest in, for the coming years.

Tidbits

Hindustan Unilever has received a $226 million tax demand from Indian authorities for FY2020–21, disputing valuations in related-party transactions and certain depreciation claims.

Source: Reuters

Adani Power has emerged as the lowest bidder for Assam’s 3.2-GW coal power tender, which has already received regulatory approval from the state electricity commission. The company plans to expand capacity to 42 GW by FY2032 through a ₹2 trillion investment, with the first 12 GW expected by FY2030.

Source: Reuters

Ford will revive its Chennai plant with a ₹3,250-crore investment to produce next-generation engines under a new powertrain project. The facility, expected to start production by 2029, will have a capacity of 2.35 lakh engines annually and create over 600 jobs, primarily for export markets.

Source: Hindu Businessline

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Kashish

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉