BRICS is becoming a Global Power Bloc

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Trump, Tariffs, and the Rise of BRICS: A New Economic Era?

Europe’s defence spending spree

Trump, Tariffs, and the Rise of BRICS: A New Economic Era?

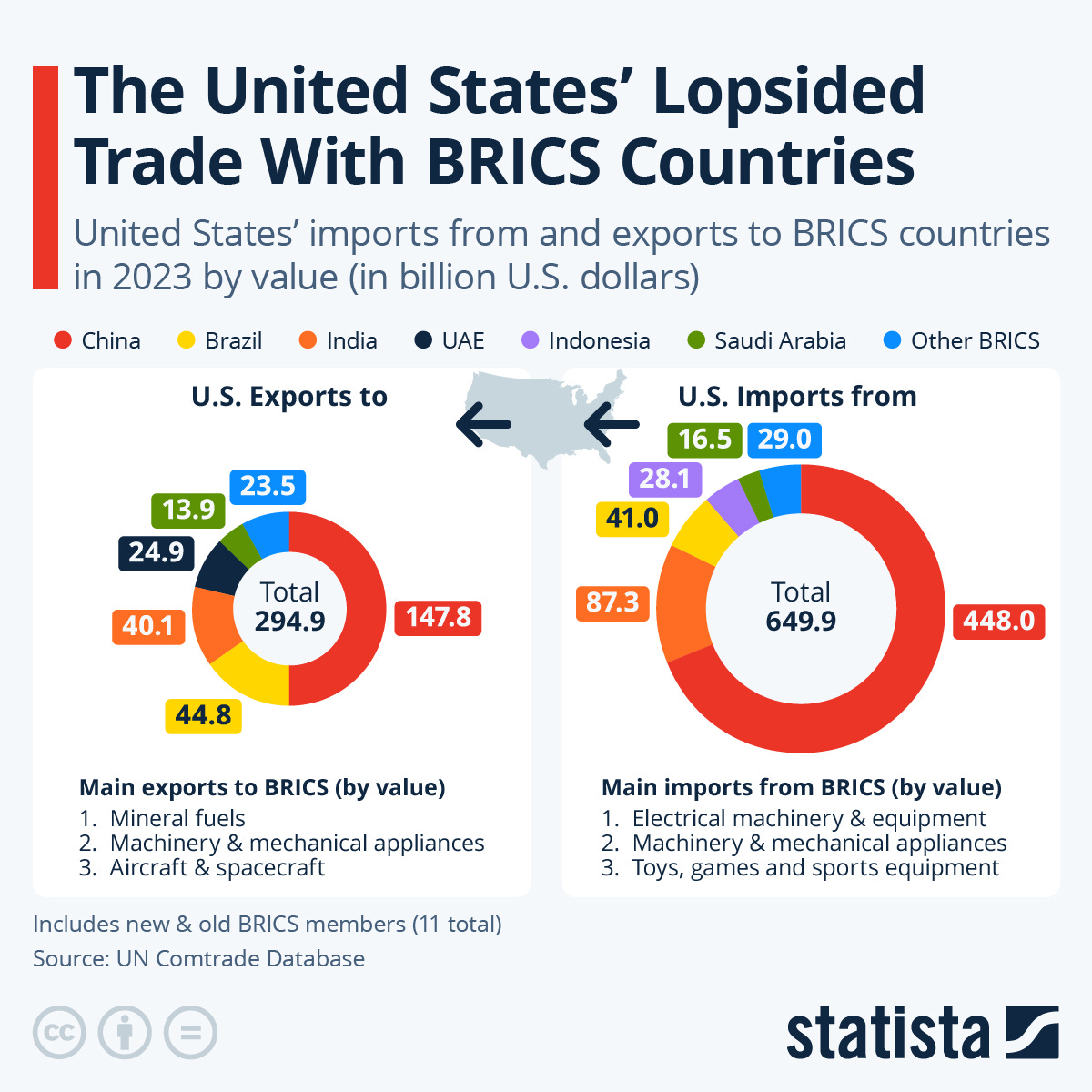

With Donald Trump back in the White House and threatening a return of the high tariff era, this BRICS bloc has taken on renewed significance. So let's break down what BRICS is, how it's evolving, and why it matters more than ever in today's fragmenting world economy.

BRICS basics

So what exactly is BRICS? Originally, it stood for Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa - five major emerging economies that formally came together as a bloc in 2009. But this coalition has been expanding, and it now includes Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates, and Indonesia, which became the tenth member just this January.

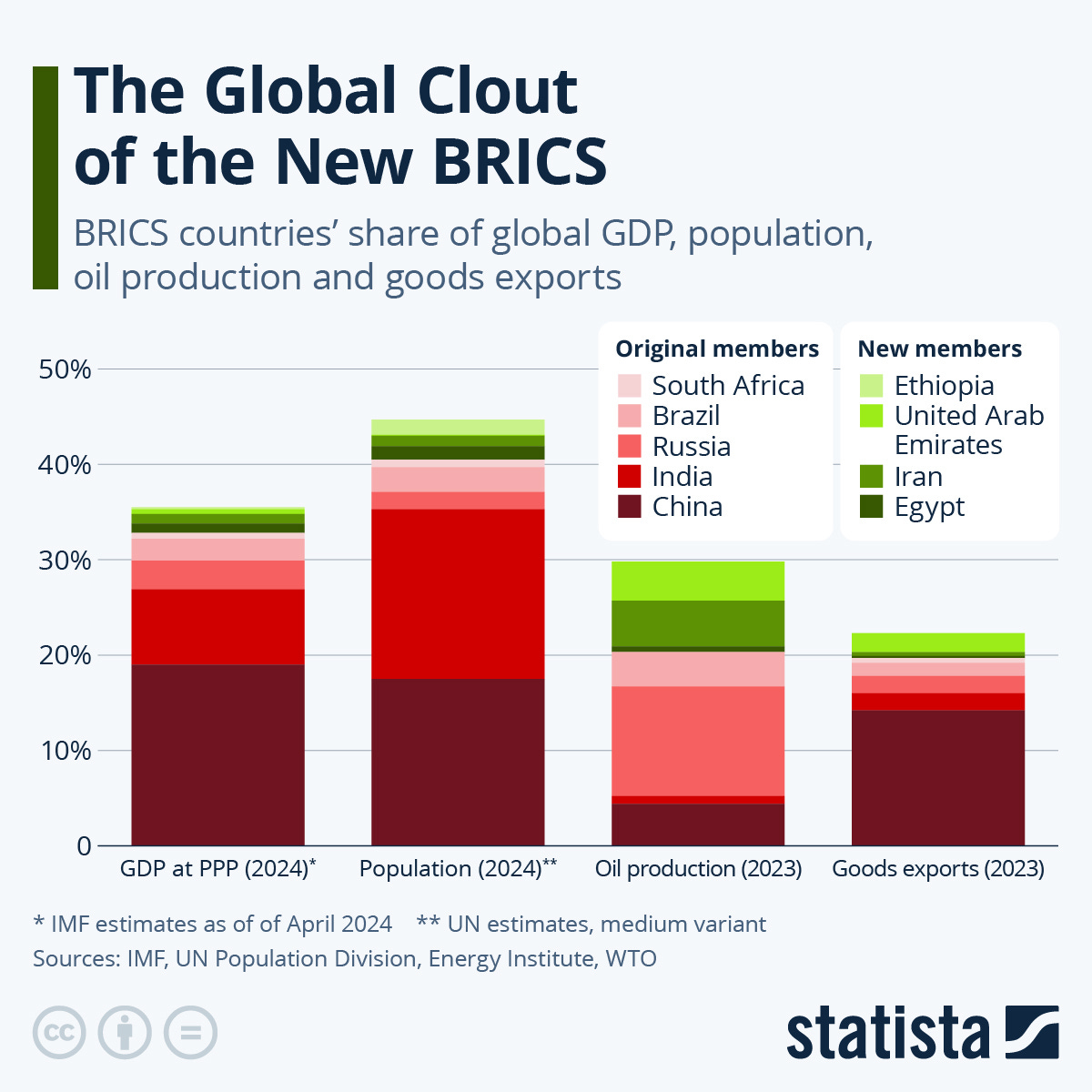

These aren't just random countries clubbing together - this is serious economic weight we're talking about. The BRICS nations collectively represent about 45% of the world's population, generate more than 35% of global GDP when measured in purchasing power parity, and produce 30% of the world's oil.

And they've been busy building institutions too - like the Contingent Reserve Arrangement in 2014 with initial funding of $100 billion, and the New Development Bank in 2015. These institutions are clear alternatives to Western-dominated ones like the IMF and World Bank.

Growing fragmentation

Now, the rise of BRICS isn't happening in isolation. According to research from the IMF published recently, we're seeing what they call "geoeconomic fragmentation" - essentially policies that reverse global economic integration.

The IMF paper notes that after decades of increasing global economic integration, we're now facing serious fragmentation risks. As they put it, "The post-GFC era has seen a leveling-off of global flows of goods and capital, and a surge in trade restrictions." This was then exacerbated by the pandemic and Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which according to them "further tested international relations and increased skepticism about the benefits of globalization."

This fragmentation isn't just theoretical - it's showing up in the data. The IMF points out that mentions of keywords like "reshoring," "near-shoring," and "onshoring" have increased significantly in company earnings calls. Businesses are actively changing around their supply chains guided by government policies rather than pure efficiency considerations.

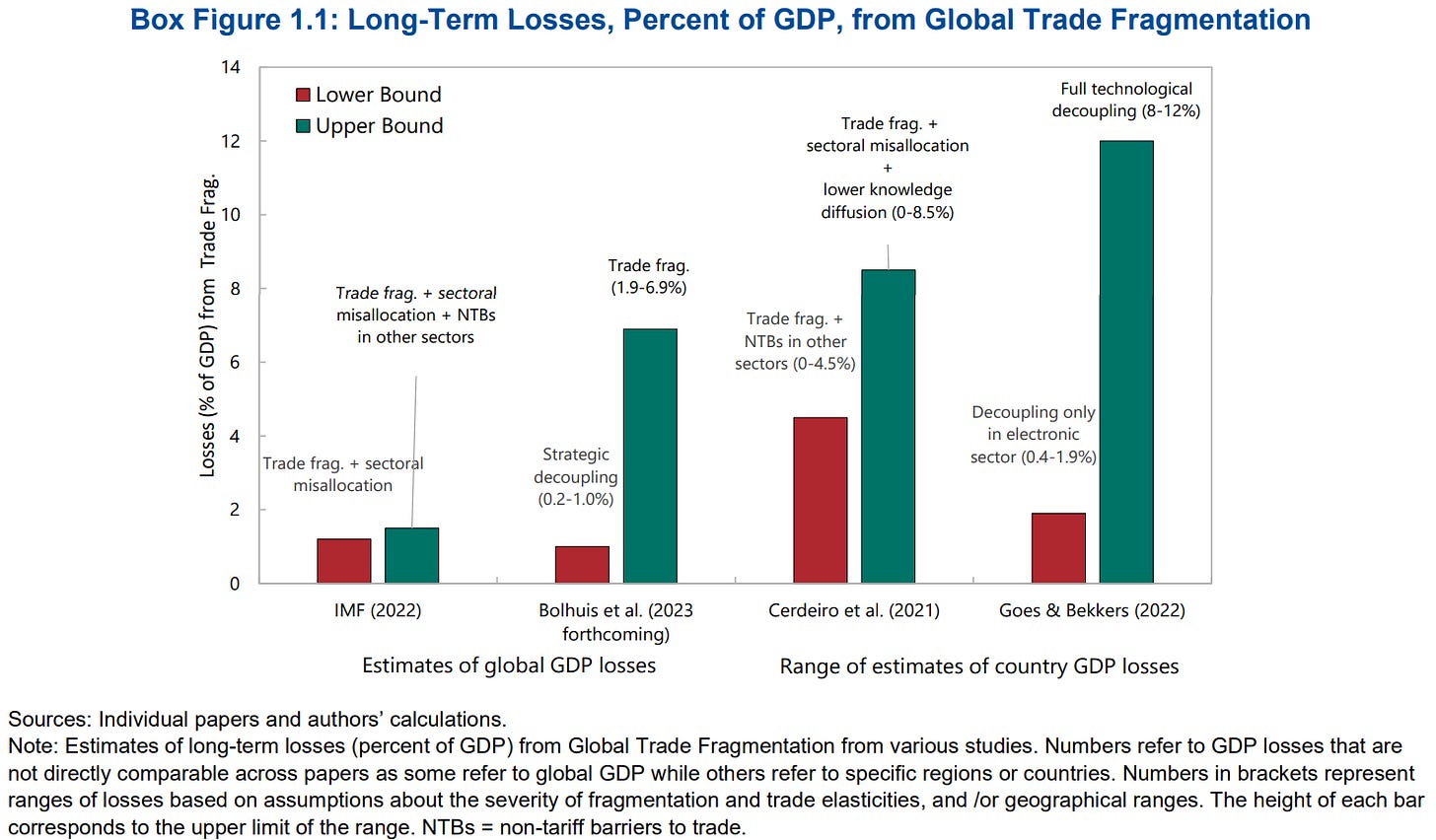

And here's where it gets really concerning. The IMF estimates that depending on how severe this fragmentation becomes, it could cost the global economy anywhere from 0.2% to 7% of GDP. If technological decoupling is added to the mix, some countries could see output losses of 8% to 12%.

It's in this context of growing global economic divisions that BRICS has gained renewed importance - as both a symptom of fragmentation and potentially an accelerating force for it.

Motivations of the original five

So what drives each of the original BRICS members? A recent report by the Carnegie Endowment report provides us with experts’ views on what could be each country's motivation.

For Brazil, Oliver Stuenkel identifies four main benefits: prestige, geopolitical influence, closer ties with China, and "insurance" against diplomatic isolation. Being part of BRICS effectively puts Brazil in the same league as major powers like China, India, and Russia, boosting its global standing. It also gives Brazil a safe haven during periods when it might face isolation from the West.

Alexander Gabuev says Russia now has three primary interests in BRICS: First, being seen as part of a dynamic group of non-Western powers shaping the post-American world order. Second, developing tools for trade, finance, and investment outside of U.S.-dominated mechanisms - which has become crucial for the Kremlin amid Western sanctions. And third, maintaining high-level diplomatic contacts at a time when Putin faces international restrictions on travel.

India's perspective is more nuanced, as explained by Ashley Tellis. While India has close ties with Russia and South Africa, its relationship with China remains "persistently rivalrous." India and Brazil are both working to prevent BRICS from becoming too anti-Western as other countries may want. For India, BRICS provides an alternative stage for leadership, helps advance multipolarity in global affairs, and allows it to claim leadership of the Global South.

Tong Zhao notes that China sees BRICS as a "strategic bridge" to harness and shape non-Western countries' power to reform the international order. For Beijing, BRICS serves as a hedge against Western decoupling, strengthening its energy, food, and supply chain security. It also helps advance de-dollarization and the internationalization of the renminbi.

South Africa, according to Gustavo de Carvalho and Steven Gruzd, views BRICS as a platform to amplify its global influence and push for reforms in institutions like the UN Security Council, IMF, and World Bank. For Pretoria, BRICS offers alternatives to Western-dominated financial systems, with the New Development Bank becoming an important funding source for infrastructure.

The evolution of BRICS

The Carnegie report gives us fascinating insights into how BRICS has evolved. The group started with a more limited focus - primarily as a club for emerging economic powers. But over time, its ambitions have grown substantially.

Russia, the first country to try turning this loose grouping into a political club, initially saw BRICS as a way to supplement institutions like the IMF, and redistribute voting rights from developed to developing countries. But as its relations with the West deteriorated, the Kremlin began to see BRICS as a tool to make the world less U.S.-centric.

China's vision for BRICS has also expanded dramatically. What started as primarily an economic and trade cooperation platform has evolved to include political and security issues. Beijing has successfully steered BRICS toward a comprehensive framework built on three pillars: economy and finance, politics and security, and cultural and people-to-people exchanges.

For China, BRICS complements its other global initiatives: the Belt and Road Initiative's geoeconomic focus and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization's geopolitical-security role.

The ongoing expansion of BRICS membership marks another significant phase in its development. The inclusion of countries like Iran and the UAE signals a geographic diversification that increases the coalition's global reach and resources.

The new members’ perspectives

The new members bring a fascinating array of motivations to BRICS, creating a more diverse and complex coalition. Rather than operating from a single playbook, these countries each see unique opportunities through their membership.

Egypt and Ethiopia - the two African additions - share economic motivations but with distinct priorities. Egypt, facing chronic dollar shortages, is particularly focused on expanding trade in national currencies and securing new financial aid channels. Meanwhile, Ethiopia sees BRICS as a vehicle for infrastructure development and climate resilience, with Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed highlighting how membership aligns with the country's "Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda."

In Asia, Indonesia's entry represents what Elina Noor calls the epitome of Jakarta's "free/independent and active" foreign policy. President Prabowo Subianto has been blunt about it by saying "Indonesia can't be tied to specific blocs but aims to be everywhere." This strategic flexibility mirrors Southeast Asia's traditional balancing approach amid great power competition.

The Middle Eastern additions reveal perhaps the most contrasting motivations. Iran views BRICS through an overtly geopolitical lens as Karim Sadjadpour explains. Tehran has consistently sought to "drive America out of the Middle East" and "dismantle the U.S.-led world order" since its 1979 revolution in Sadjadpour’s words. BRICS membership perfectly advances this long-standing agenda while potentially easing its economic isolation.

The UAE, by contrast, emphasizes that joining BRICS isn't about counterbalancing Western relationships but rather expanding its strategic options. As a global trade and finance hub, the Emirates brings substantial economic weight to the group while gaining access to the growing markets of other BRICS nations. Unlike Iran, the UAE maintains that BRICS membership complements rather than replaces its Western partnerships.

What unites these diverse new members, despite their differences, is a shared desire for greater representation in global economic governance and a hedge against an increasingly unpredictable United States. As Trump returns to the White House threatening tariffs and economic nationalism, these countries see value in having alternative diplomatic and economic partnerships - even if they maintain varying degrees of engagement with the West.

Internal contradictions

Despite being under the same umbrella, BRICS is far from a monolithic bloc. The coalition faces significant internal contradictions and competing interests that could limit its effectiveness.

The most obvious tension exists between China and India. While China dominates the bloc economically and increasingly sets its agenda, India remains wary of becoming entangled in Chinese initiatives that might undermine its own strategic autonomy or security interests.

Brazil, too, has reservations about the direction of BRICS. Oliver Stuenkel notes that Brazil was unable to stop the recent expansion of BRICS - which it long opposed out of fears it would lose prestige, have limited access to Chinese President Xi Jinping, and see both China's and Russia's influence grow within the group. Brazil continues to seek a balance, trying to prevent BRICS from becoming too anti-Western which would complicate its important ties with the United States.

South Africa, despite its close relationship with India, has "strong sympathies for Russia, increasingly close ties with China, and a striking suspicion of the West," creating a complex web of relationships within the group.

These internal tensions became evident during discussions about expanding BRICS membership. According to the Carnegie report, "Chinese-Russian collusion quickly overwhelmed Indian (and Brazilian) diffidence" regarding expansion.

There's also disagreement about how directly to challenge the dollar-dominated financial system. While Russia and Iran are eager to create alternatives to the dollar, countries like India have dismissed ideas of creating a BRICS currency or promoting de-dollarization.

Conclusion

So where does all this leave us? BRICS represents both a challenge and an opportunity for the global economic order. Its expansion reflects genuine dissatisfaction with aspects of Western-led institutions and a desire for more equitable global governance. At the same time, the coalition's internal contradictions may limit its cohesion and effectiveness.

What's clear is that with Trump's return to the White House and his combative stance on trade, BRICS is likely to gain even more significance. As the Carnegie report concludes, the potential of BRICS to fulfill its aspirations "hinges on which vision of the future of world order ultimately wins out" and on whether the U.S. under Trump will "countenance a more egalitarian global order rather than force middle powers to choose between BRICS membership and friendly relations with the United States."

So as this global economic realignment continues, we'll be keeping a close eye on BRICS and its evolving role in the international system.

Europe’s defence spending spree

Europe is stuck in what many analysts are calling the most precarious security situation since the Cold War. The catalyst? A perfect storm of geopolitical developments.

First, you've got Russia's ongoing war in Ukraine, now in its fourth year with no end in sight.

But what's really sent shockwaves through Brussels and European capitals is the dramatic shift in American policy. President Trump's administration has essentially pulled the plug on Ukraine support. Remember that bizarre and frankly disturbing meeting at the White House where Trump and Vice President Vance publicly humiliated President Zelensky? That was the clearest signal yet that Ukraine could no longer count on American backing.

But it goes beyond Ukraine. Trump has repeatedly questioned NATO's very existence and made it clear that Europe needs to fend for itself. As the Heinrich Böll Foundation put it in their recent analysis, "Trump only understands the language of deals and strength." His stance has created what European officials are calling an urgent "security emergency."

Intelligence agencies across Europe estimate Russia would need about five years to reconstitute its military capabilities to potentially launch an attack on NATO territory. That five-year window is driving a sense of urgency across European capitals.

This new reality has forced a remarkable shift in European thinking. After decades of under-investment in defense and reliance on American security guarantees, Europe is waking up to a stark reality: it needs to rapidly build its own defense capabilities.

Wait… Why do we care?

You might be wondering why we're covering a European defense spending spree on our show. The amount of money they’re putting in makes it deeply relevant for the entire world. This massive reallocation of resources – we're talking hundreds of billions of Euros – will create serious ripple effects across global defense markets, potentially including Indian defense stocks and contractors. Indian defense companies that have partnerships with European firms or export capabilities could find new opportunities open up as Europe ramps up procurement. So this isn’t just a story for geopolitical intrigue, it also has investment implications.

To understand what's happening, we're turning to some fascinating analysis from Bruegel, one of Europe's leading economic think tanks. They've published several in-depth reports that give us a clear picture of just how significant this shift really is.

The scale of EU defense spending

So let's talk numbers. How much is Europe actually planning to spend?

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced what she's calling the "ReArm Europe" plan earlier this month. According to her press statement, this package aims to mobilize close to €800 billion for European defense – or around $875 billion. That is, for context, more than 10x India’s defence budget for this year.

The plan has several components. The first is activating what's called the "national escape clause" in Europe's budget rules, which would allow countries to take on deficits while increasing defense spending by up to 1.5% of GDP without triggering deficit penalties. We’ll get to this shortly. This alone could create fiscal space of about €650 billion over four years for defence spending.

The second component is a new €150 billion loan instrument called "Security Action for Europe" or SAFE, which will provide loans to member states specifically for defense investments.

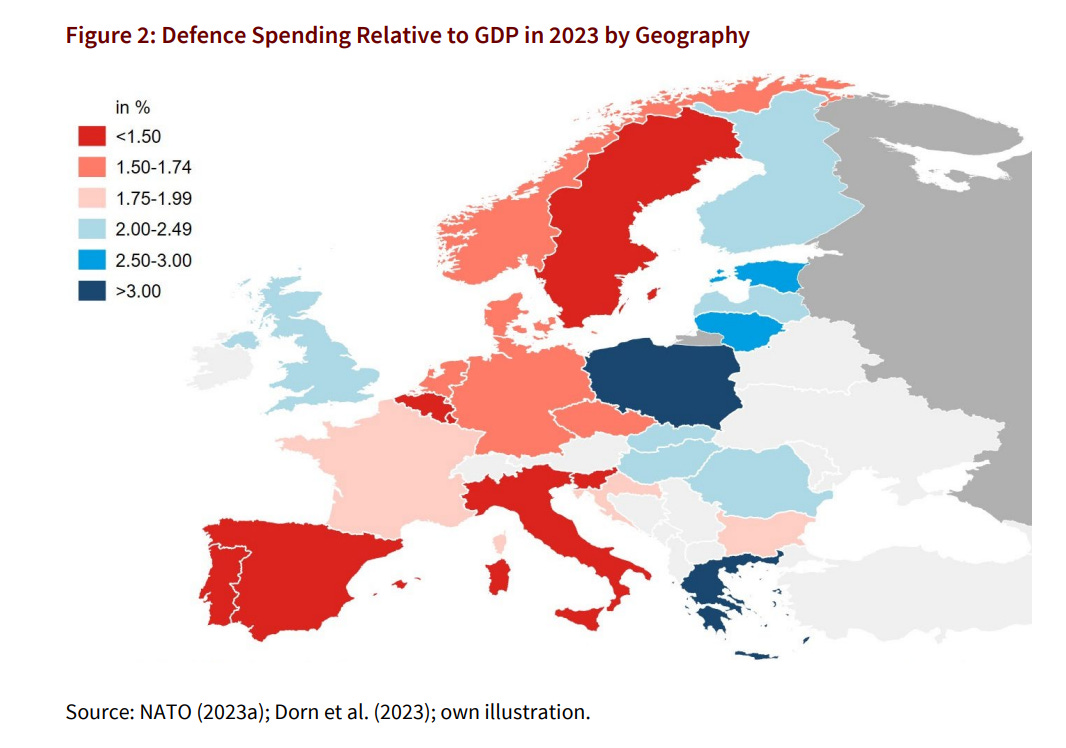

But here's a reality check from Bruegel's analysis: European NATO members currently face a massive shortfall in defense spending. According to their calculations, to reach the proposed NATO target of 3.7% of GDP (up from the previous 2% target), most EU countries would need to increase spending by about 1.7% of GDP on average.

Most of the EU isn’t nearly there yet. Only Poland is currently spending above that 3.7% target. Countries like Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain face huge spending challenges, each needing to increase defense spending by more than 2% of GDP.

How would things look if they all met their commitments? In total, European NATO members need to spend an additional €275 billion annually to reach this target. Compare that to Russia, which is spending around €120 billion on defense — roughly a third of all Russian government spending.

But there are many gaps that all that money must plug. The White Paper for European Defence Readiness 2030, just released on March 19th, identifies seven critical capability gaps that European countries need to address urgently: air and missile defense, artillery systems, ammunition and missile production, drones and counter-drone systems, military mobility, AI and cyber capabilities, and strategic enablers like communications and surveillance.

The fiscal mechanics

How does all this funding actually work?

The EU has strict fiscal rules under what's called the ‘Stability and Growth Pact’, or SGP. The pact typically limits government deficits to 3% of GDP and requires countries with debt above 60% of GDP to reduce it over time. Without some sort of flexibility or exemption, many countries simply couldn't increase defense spending by the needed amounts without violating these rules and potentially facing penalties.

That's where those "escape clauses" come in. There are two types of escape clauses: a "general escape clause" for EU-wide recessions, and a "national escape clause" for country-specific shocks.

Now, as Bruegel points out, there’s a stigma associated with the national escape clause. Since each country technically needs to individually request its activation, there's a risk that financial markets might perceive this as a sign of fiscal weakness.

So why doesn’t the EU just use the general escape clause? That would be politically easier and potentially give countries more flexibility, after all. Well, the problem is that the conditions for activating it – specifically, an EU-wide severe economic downturn – simply don't exist right now. The security threat, while serious, doesn't qualify under the general clause provisions.

That’s why the Commission is using the national escape clause, arguing that the security situation constitutes "exceptional circumstances." This allows countries to deviate from their normal fiscal plans for up to four years, starting from 2025. To counter the stigma, the Commission has invited all EU countries to request the clause simultaneously, essentially removing the stigma by making it a collective action.

But there is some nuance here. The impact varies dramatically depending on a country's debt level:

For low-debt countries like the Netherlands or Germany, the escape clause isn't actually necessary. They already have room to increase defense spending without triggering penalties, as long as their deficits remain below 3% of GDP.

For high-debt countries like Italy, France, and Belgium, who are already under excessive deficit procedures, the escape clause could make a crucial difference. It gives them room to increase defense spending without facing further penalties or market backlash.

Now, the Commission has proposed a 1.5% of GDP cap on extra defense spending under this clause. To Bruegel, though, the legal basis for enforcing this cap is questionable. Countries could realistically exceed this limit without real consequences.

Unanswered questions

Although this seems like a European spending program, once you get into the weeds, this doesn’t seem like Europe is jointly coordinating anything. Unlike the COVID recovery fund, most of this new financing will come from national borrowing, not EU-level debt. The €150 billion SAFE loan facility is the only common borrowing component, and even this involves loans to individual countries — not grants.

This raises questions about the efficiency of Europe's approach. Without strong incentives for joint procurement and standardization, there's a risk that each country will pursue its own defense projects. Their militaries, as a result, could become fragmented, and duplicate each others’ abilities.

As Luigi Scazzieri at the Centre for European Reform points out, "Neither activating the national escape clause nor the SAFE loans are structured in a way that is likely to meaningfully change member-states' calculations on whether to co-operate or work nationally."

Another key question is whether SAFE loans will actually be attractive to all member states. Countries like Poland with higher borrowing costs (around 6%) might benefit from the EU's lower interest rates (around 3%). But for countries that can already borrow cheaply, the minimal savings may not justify the administrative complexity.

But will high-debt countries actually use this fiscal flexibility? There are reasons to be skeptical. Countries like Italy or Spain, facing high borrowing costs and deficit concerns, might be unwilling to significantly increase defense spending — especially given limited public support. Italy and Spain's reluctance is evident from their objection to the original "ReArm Europe" name, which they felt had militaristic overtones.

Finally, there's also uncertainty about how Ukraine fits into this picture. The EU's white paper emphasizes integrating Ukraine's defense industry with Europe's and treating Ukraine as an EU member for defense purposes. But aspirations aside, there isn’t really a specific funding mechanism they suggest.

Germany's debt brake and new complications

There’s another development that's shaking up this whole picture: Germany's decision to reform its constitutional debt rules.

For decades, Germany has maintained a strict "debt brake" that severely limits government borrowing. It was the EU’s resident fiscal hawk. But suddenly, in an extraordinary shift, the new German government has pushed through a reform that permanently exempts defense spending from these borrowing limits. This is on top of creating a massive €10 trillion infrastructure fund.

These moves, to Breugel, create a paradox. On one hand, Germany's debt situation remains sustainable – even with higher defense spending, its debt-to-GDP ratio would likely stabilize below 100%, well within manageable limits. But on the other hand, Germany's move potentially undermines the entire EU fiscal framework. As Europe's largest economy, Germany has always been the strongest advocate for strict budget rules. Now it's essentially saying those rules don't apply to defense spending.

This creates a two-tier situation: Germany can borrow freely for defense while other countries, particularly high-debt Southern European nations, remain constrained by EU fiscal rules. This could lead to tensions and calls for a comprehensive rethink of the EU's fiscal framework.

As Pench notes in the Bruegel paper, Germany's move "upends the rule-based system that underpins fiscal policy coordination in the euro area". This could increase pressure on the European Central Bank to intervene in bond markets if countries with less fiscal space face refinancing difficulties.

Conclusion

So what are the takeaways from all this?

Europe is embarking on its most significant defense buildup since the Cold War, driven by a profound shift in the security landscape. But beneath the large headline figures lies a complex web of fiscal rules, national priorities, and political constraints. The escape clauses provide flexibility, but questions remain about implementation, coordination, and whether countries with high debt burdens will actually increase spending.

In all of this, Germany's debt brake reform adds another layer of complexity, potentially undermining the EU's fiscal framework while giving Germany a freer hand in defense spending than its European partners.

For investors, particularly those watching defense sectors globally, this European pivot creates significant opportunities but also uncertainties. Will the money actually materialize? Will it flow to European defense firms or also benefit international contractors, including potentially those from India? And how will markets react to the increased borrowing?

As the Atlantic Council recently noted, five years is a brief timeframe for Europe's rearmament. The EU has laid out a good roadmap, but the real challenge now is moving from identifying problems to implementing solutions.

Tidbits

Adani’s Kutch Copper Smelter Nears Launch Amid Global TC/RC Squeeze

Source: Reuters

Adani Enterprises is set to commission its Kutch Copper smelter—India’s largest—within the next four weeks. The facility recently began producing its first anodes as part of its Phase 1 commissioning. This comes at a time when global treatment and refining charges (TC/RCs) have turned negative, pushing Asian smelters into losses due to tight copper concentrate supply. Once fully operational, the smelter is expected to reduce India’s dependence on imported refined copper, especially after the 2018 shutdown of the Sterlite plant, which once supplied 40% of domestic refined copper. Copper prices on the London Metal Exchange rose 3.8% to $8,939 per tonne following the announcement and related global developments. Environmental approvals for expansion are already in place, indicating long-term ambitions for the metallurgical complex. Adani’s move coincides with rising domestic demand driven by infrastructure and electrification. The project was discussed during the International Copper Association’s conference in Santiago.

Apple Flies 15 lakh iPhones from India to US to Dodge Tariffs

Source: Reuters

Apple has shipped around 15 lakh iPhones, weighing 600 tons, from India to the US using chartered cargo flights in response to the recent 125% tariff hike on Chinese smartphones. The exported phones, primarily high-end models like the iPhone 16 Pro Max, were manufactured at Foxconn’s Chennai plant, which produced 2 crore iPhones last year and is now operating on Sundays to meet a 20% higher production target. Foxconn’s exports from India to the US surged to $770 million in January and $643 million in February 2025, compared to $110–331 million in the four months prior. Apple’s move aims to avoid the tariff shock, which could have raised the iPhone 16 Pro Max price from $1,599 to $2,300.

Airbus to Boost India Sourcing to $2 Billion Annually by 2030

Source: Business Line

Airbus SE has announced plans to increase its annual sourcing from India to $2 billion by 2030, marking a nearly 43% jump from current levels. In 2024, the aerospace giant sourced $1.4 billion worth of components from India, a 40% rise compared to the previous year. This is a significant increase from the $500 million worth of procurement recorded in 2019. The move highlights India’s growing role in Airbus’s global supply chain as the country’s aviation market expands rapidly. Indian carriers currently have a pending order book of about 1,800 aircraft, among the largest globally, shared between Airbus and Boeing. At an event in New Delhi, Airbus also announced a partnership with Mahindra Aerostructures Pvt., which will manufacture the main fuselage for Airbus’s H130 single-engine helicopters. Deliveries from Mahindra are expected to begin in March 2027.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Bhuvan and Pranav

📚Join our book club

We've recently started a book club where we meet each week in Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you'd like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Why not amend the Commission guidelines / rules to increase the threshold from 1.5% to 3% of GDP spend on extra defence spending so that no country faces penalties? Is that very difficult to do?