Blinkit is chasing growth over margins, and Bajaj isn’t happy with KTM | Who said What? S2E16

Hi folks, welcome to another edition of Who Said What? I’m your host, Krishna. For those of you who are new here, let me quickly set the context for what this show is about.

The idea is that we will pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualize things around them. Now, some of these names might not be familiar, but trust me, they’re influential people, and what they say matters a lot because of their experience and background.

So I’ll make sure to bring a mix—some names you’ll know, some you’ll discover—and hopefully, it’ll give you a wide and useful perspective.

Why Blinkit chose growth over margins

Last quarter, Blinkit’s management spoke about what they called a structural shift in their business. They were moving from a marketplace model, where other sellers list and sell on the platform, to an inventory-led model where Blinkit owns what it sells.

CFO Akshant Goyal had said:

“most of our business will move to inventory ownership and margin accretion should also happen in that timeframe.”

The thing is, once you own the stock, you don’t just earn a small commission anymore. You earn the full spread between the buying price and the selling price. Think about it: if Blinkit buys Maggi, say, for all its operations across India, how much cheaper could it get it? Meanwhile, they also maintain product quality, reduce stock-outs, and maybe even improve overall customer experience. All of this could turn into more profits, and greater competitive advantage.

But there’s another side to this. The moment you start owning stock, you also start holding cash in that stock. Every stock that sits in the warehouse is money that’s already been paid out but not yet earned back. This is what you would call working capital.

Back in Q1, Akshant had said this would increase. At full scale, they expected roughly eighteen days of working capital, or about five percent of net order value. But the company also made a point that not all inventory-heavy models are the same. The way Blinkit holds and moves stock is very different from how a supermarket does it.

On the concall, when an analyst compared Blinkit to DMart, Albinder explained why that comparison doesn’t really hold. A retailer like DMart carries big, slow-moving categories — general merchandise, home goods, electronics — items that can sit on shelves for weeks. Blinkit, on the other hand, deals mostly in groceries and daily-use items that move much faster. Stock comes in and goes out several times a week. Because of that speed, the amount of inventory Blinkit needs to keep at any given time is far smaller.

So yes, working capital rises when Blinkit owns inventory, but it’s still lighter than a traditional retailer’s because the stock turns over quickly. The faster the product moves, the less cash stays stuck in it.

This quarter, that shift is visible in the numbers. About 80% of Blinkit’s sales now come from its own inventory. And with that, working capital has started to build up. The company now holds roughly twelve days of sales worth of stock which is about of ₹2,000 crore of cash sitting inside the system, most of it in the quick-commerce business.

That’s the cost of control. When Blinkit adds a new category, or opens a new warehouse, it also locks up more cash in goods that haven’t been sold yet. Earlier, when the platform was a marketplace, that inventory sat on someone else’s balance sheet. Now it sits on theirs.

And while this change was meant to help margins, the improvement hasn’t shown up yet. In the shareholder letter, management admits, “while absolute losses decreased, the reduction in loss or margin expansion was below expectations.”

That line says a lot. The company had expected margins to expand faster, but chose to stay aggressive instead. Marketing spends were up about four times year-on-year. They opened more stores, built new capacity, and focused on winning market share. In other words, instead of letting the efficiency gains from owning inventory flow straight into profits, they used that headroom to grow faster.

In theory, the new model should make each order slightly more profitable over time because Blinkit now controls what it buys, how it prices, and how quickly it moves stock but that improvement isn’t visible yet. The short-term picture still looks flat because the company is using those gains to fund growth.

And that’s what this transition really looks like when you zoom in. The accounting change lands first: the day you start buying inventory, cash goes out. The benefits ie.. steadier supply, better prices, happier customers, take longer to build. For a while, the business looks heavier before it starts looking more profitable.

Albinder even says: “If we have to choose between high quality sustainable growth, and a short-term sacrifice of margins, we are in a position to choose the former given our strong balance sheet.”

Bajaj doesn’t seem happy with KTM

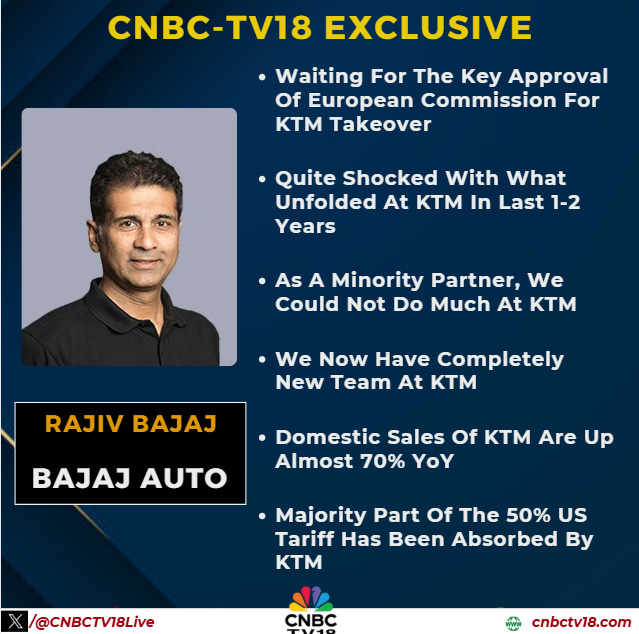

In an interview with CNBC-TV18, Rajiv Bajaj said: ‘I’m quite shocked with what unfolded at KTM in the last 1-2 years,’ and that ‘corporate greed’ is the single-biggest reason for corporate demise.

Now, that’s a bold statement, especially from someone like him. If you are unaware of why he said this, just sit tight. Let me explain what’s going on.

Bajaj Auto isn’t just KTM’s Indian distributor. It’s also been the company’s manufacturing and equity partner for a long time. Through a joint holding company with the CEO of KTM, Bajaj owns about 49% of KTM’s parent group, Pierer Mobility AG.

In India, KTM lives inside Bajaj’s Probiking division, the same one that runs Triumph. It’s not Bajaj’s biggest business by revenue, but it’s important: it brings technology, exports, and a bit of global sheen. Last quarter, Bajaj sold around 26,000 KTMs and Triumphs in India about 20% more than a year ago and crucially, restarted KTM exports that had been frozen for months.

That pause is where the real story begins.

Over 2023 and 2024, KTM’s parent group started running out of cash. They’d grown a little too fast. Each expansion was built on borrowed money. And, when interest rates were near zero, that debt barely mattered. But once inflation hit and rates rose it was quite brutal.

After the Ukraine war, energy prices went crazy, labour got expensive, and raw materials stayed high. KTM was always proud of building their bikes in Austria - you know, that whole “Made in Europe” thing but suddenly they’re competing with Indian and Chinese manufacturers who can make the same quality bikes for way cheaper.

And on the demand side, the post-pandemic motorcycle rush was fading. Dealers had unsold inventory, consumers were tightening up, and cash stopped coming in.

By the end of 2024, KTM couldn’t meet its debt payments. It entered insolvency protection in Austria, a court-supervised process where creditors decide how to keep the company alive.

By early 2025, the Austrian court gave KTM a choice: either raise new funds to pay creditors or face liquidation. The number on the table was roughly €600 million.

But no European bank wanted to touch it. Investors were wary, KTM’s management was being accused by creditors, led by a US hedge fund, of designing a rescue plan that protected shareholders more than lenders. It was messy, public, and political.

At that point, Bajaj was still a minority shareholder watching from the sidelines. But staying out wasn’t really an option. KTM collapsing would have hurt Bajaj directly, it would mean supply disruptions, brand damage, and the loss of a partner it had spent years building with.

So Bajaj stepped in.

Through a mix of loans and convertible instruments worth about €800 million, Bajaj arranged the cash KTM needed to meet its obligations. That money allowed KTM to pay creditors, get the court’s approval, and formally exit insolvency in June 2025. But this wasn’t charity. In return, Bajaj secured the right to take control. Once European regulators finish clearing the takeover, Bajaj Auto will become the majority owner of KTM’s parent company.

On Bajaj Auto’s last quarter’s earnings call, CFO Dinesh Thapar laid out how the crisis unfolded:

“We suspended exports to the KTM business through quarter 4 because we had anticipated a risk on our receivables through dependency of the restructuring process. With that having been resolved in May, we resumed exports, and that in turn has helped both the exports performance and margin delivery.”

He also said:

“The insolvency court in Austria … on 16 June 2025 confirmed the restructuring plan … the entire restructuring proceedings have now been concluded. We have progressed substantially on seeking regulatory approvals … Upon successful completion, we plan to take a more controlling position, exercise the call options, and then start to work … to restore financial discipline and reposition the business for sustainable value creation and growth.”

That phrase — restore financial discipline — quietly sums up the whole story. It’s an acknowledgment that KTM’s problems weren’t just about the economy; they were about decisions.

That’s it for this edition. Thank you for reading. Do let us know your feedback in the comments.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

The newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

I don’t full grasp blinkit’s business, so I’m curious to know whether they also own the dark store, or it on lease (which is likely the case). But what if it was like a franchisee, say, Burger King? operated by a local who paid for the license? LMK if my question is all over the place

Your article does a very good job highlighting the strategic logic behind Blinkit’s growth-over-margin posture and the transitional costs the company is accepting.