Bike taxis get a policy nod

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

A green light for white plates? The story of bike taxis

A financial health check for India’s companies and households

A green light for white plates? The story of bike taxis

India just decided to clear out a decade’s worth of confusion around bike taxis.

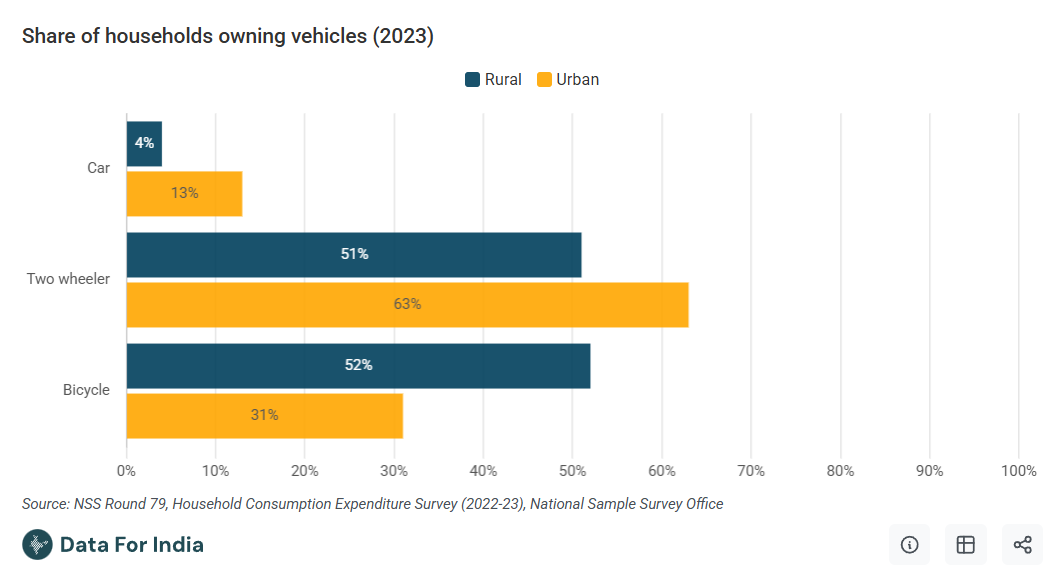

The central government, at least, has given a giant nod to bike taxis across the entire country — passing the ‘Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines 2025’ (what we’ll call ‘MVAG 2025’, going ahead). This could be transformational. We’re a country where more than half of households own a two-wheeler; in fact, even adjusted for our population, India has the highest number of two-wheelers in the world. Meanwhile, commutes (and commute times) are a perennial challenge for urban Indians.

Bike taxis cut through this problem. They (a) create certainty around a cheaper, faster way of getting around, while (b) finding a way of monetising all those two-wheelers that Indians own.

As you probably know, we already have bike taxis on our roads. According to Allied Market Research, India's bike taxi market is currently worth $50 million. But the market is nowhere close to maturity. With legal certainty, it could be much larger — some estimates even suggest that this could be a $1.4 billion market by 2030. The MVAG 2025 could just be the catalyst

But here's the catch: While the central government has provided a new framework, it doesn’t call the shots. It’s ultimately on individual states to decide if they actually want to enable them. The guidelines just give them the tools to do so if they choose — but the choice, ultimately, sits with the states alone.

This is an old tussle, which has seen many twists and turns. It all started many years ago, in a small coastal state that had a basic transport problem.

Where It All Started

In the late 1970s, Goa was running into a major challenge. The state was full of narrow, winding roads, connecting its small villages and beaches. Buses were too big for these roads, cars too expensive, and tourists needed a quick way to get around.

Locals came up with a clever solution: use motorcycles as taxis.

By 1981, Goa became the first state in India to make motorcycle taxis completely legal. Back then, these were practically unheard of the entire world over — at least not formally. These would be driven by "pilots", who wore bright yellow helmets, and knew every shortcut around. They became a part of Goa’s landscape, as much as its beaches and seafood.

For decades, this remained a Goa-only thing. Most states simply weren’t interested in motorcycle taxis. In 2004, the central government tried formalising Goa’s experiment. Through a notification, it allowed motorcycles to be classified as ‘transport vehicles,’ i.e., vehicles that can legally carry people or goods for money. But there were no takers. It took another eleven years for the second state to follow suit — when Haryana experimented with the idea in 2015.

The private sector, however, was much more keen on the idea. In 2015, the start-up Rapido tried bringing the taxi aggregator model to motorcycles, adopting the playbook that companies like Uber had taken with cars. Others soon followed suit. Today, Rapido controls 56% of the bike taxi market, followed by Uber and Ola.

Only, this was all happening in a legal grey area. India's main transportation law, the Motor Vehicles Act was enacted in 1988, long before policymakers could even imagine the modern world of app-based services. It just regulated permits and number plates; in its imagination, any taxi would look like the four-wheeled taxis we’re familiar with. Anyone who wanted to run a taxi would have to buy a separate commercial vehicle, which would be registered with special, yellow number plates

This wasn’t what Rapido had in mind. It was trying to create an opportunity out of the millions of two-wheelers Indians already owned. Most of their bike taxi drivers used personal motorcycles, with regular white number plates. Was this even legal? Nobody had clear answers, creating a confusion that would plague the industry for years.

In 2016, the central government pushed this question to the states, letting them decide their own rules.

Only, this created more chaos. States kept shifting their stances on the business. For instance, Delhi allowed bike taxis briefly in 2016, then banned them, then started pilot projects, before banning them again. Maharashtra went through similar flip-flops, creating confusion for both drivers and passengers.

Soon, the legal position of bike taxis was a complete jumble. Some states embraced them completely. For instance, Haryana, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, and Chandigarh all said yes and created proper rules around them. Other states, however — especially Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Madhya Pradesh — either banned bike taxis outright or made them very difficult to operate.

The opposition

Why were so many states reluctant to embrace this new means of transport?

There were many reasons, perhaps — from safety to congestion. But at least one of them was the pressure from auto rickshaw drivers.

As reasonably cheap modes of short-haul urban transport, bike taxis were direct competitors to auto rickshaws, who had long dominated the space. As Shashank Rao, who leads Mumbai's auto-rickshaw union, explained: "If bike taxis are allowed, it will threaten the livelihood of 15 lakh rickshaw drivers in Maharashtra, and their families will face starvation."

Bike taxis were cheaper than auto rickshaws. They were less regulated too; they didn't need special commercial licenses, and paid less tax. They seemed like existential threats to auto drivers, hitting their livelihood directly.

Their opposition soon created the most dramatic chapter in the bike taxi story.

Karnataka's experience shows how complicated things could get. In 2021, the state created a policy allowing electric bike taxis. Auto-rickshaw unions in Bengaluru protested heavily, however, organising strikes and getting into heated clashes with bike taxi operators. Things kept getting uglier, until Karnataka completely withdrew the policy in March 2024.

Without legal certainty, the doors for bike taxis shut. In April 2025. Karnataka's High Court held that bike taxis couldn’t operate in the state without proper regulations governing such an enterprise, and banned all bike taxis. Within six weeks, 100,000 drivers suddenly had to look for some other means of livelihood.

In these short years, though, Bengaluru had grown used to bike taxis plying the streets. Their disappearance, overnight, suddenly created havoc. Bengaluru's traffic became 18% worse within a week. Auto-rickshaw fares shot up, as competition dried up. Bike taxi regulars, meanwhile, were left stranded.

The New Framework

Karnataka’s mess, and all the general confusion across states, finally forced the central government’s hand. On July 1, 2025, they released the MVAG 2025, that clearly allowed bike taxis everywhere in India.

Part of the confusion, in fact, had come from the gaps in the central law. Under the law, the central government was to give broad guidelines on how aggregators were to be treated, which created the foundation states would build from.

The government had released one such set of guidelines in 2020. Only, there, motorcycle taxis were a grey area. The guidelines did mention two-wheelers in passing, but there was nothing around private two-wheelers being used as taxis. States could easily use this to argue that they were alright with bike taxis that were registered with a yellow plate, but nothing else.

The new guidelines, on the other hand, leave no doubt about their intent.

The new guidelines explicitly mention “non-transport motorcycles”, and nudge states to permit them. That is, it formally indicates that the government is comfortable with bikes that aren’t registered as “transport vehicles” ferrying passengers around.

To get around safety concerns, the new guidelines have extensive safety-related requirements that aggregators must ensure — from training, to insurance, to background checks, to technological solutions like GPS-tracking.

These new guidelines should bring some relief to bike taxi aggregators. It gives them a legal toe-hold, for the first time creating a concrete framework within which they can carry out their business. The central promise of a company like Rapido — that anyone with a motorcycle and a smartphone can potentially earn money ferrying customers — finally gets strong policy support.

On the other hand, auto-rickshaw drivers’ challenges remain. With more bike taxis around, they'll experience intense competitive pressure, as bike taxis compete for the very customers that auto rickshaws serve. And they’ll face all this pressure with one hand tied behind their backs — as their compliance requirements remain as extensive as ever.

Of course, all of this will only happen if states follow through.

Will states follow suit?

Ultimately, the fate of bike taxis rests in the hands of state governments.

This is clear from how the guidelines are worded. They don’t dictate that state governments must permit bike taxis — they simply suggest that states may allow aggregators to run private bike taxis. The ball, ultimately, sits in states’ courts.

To any state, this is a difficult call to make. On the one hand, this is a product with clear demand. Any state that allows private bike taxis will see more jobs, improved connectivity, and revenue generation from new licenses and fees. On the other, there’s genuine political opposition to bike taxis, often coming out of very real grievances.

The success of these new guidelines will depend on how well states balance different interests. In the balance hangs an industry that could be worth over a billion dollars.

A financial health check for India’s companies and households

The Reserve Bank of India just dropped its half-yearly Financial Stability Report.

The FSR is usually a long, terse publication, full of numbers and graphs. But if you know what you’re looking for, it’s also a treasure trove of insight into India’s economy. We won’t give you the usual summary; instead, we'll focus on something more fundamental —- the health of the two most important actors in the Indian economy: corporates and households.

The report looks at a few fundamental questions — How healthy are Indian corporates, really? Are Indian households drowning in debt or building wealth? And what's driving the dramatic shifts we're seeing in how families invest their money?

That’s what we’ll try to answer today. Let’s dig in.

Corporate India

From the outside, this probably looks like a terrible time for business — one with raging trade wars, broken supply chains, and deep uncertainty. But somehow, Indian corporates are thriving, in ways that would make their global peers jealous.

Their sales are growing by a moderate 7.1% year-on-year. But somehow, Indian companies have managed to maintain a rock-solid operating profit margin, at 16.3%. That is, Indian companies are making a healthy amount of money, even at this time.

As a result, they’re fairly comfortable paying back their loans.

The ‘interest coverage ratio’ – essentially, how well companies can pay their interest expenses – has improved across sectors. Manufacturing companies have the firepower to cover their interest payments 8.7 times over. In services, it's 2.1 times. And in IT? A stunning 44 times.

This isn’t just a matter of declining interest rates. All that happened fairly recently.

If anything, ‘weighted average lending rates’ have actually risen by 162 basis points since March 2022. That is, the effective interest rates companies pay is much higher than it was even three years ago. Corporate India is performing better despite higher borrowing costs, not because of low rates.

Another number that caught our attention was the ‘debt-service ratio’ — or how much of a company's income goes toward servicing debt. Indian companies have actually managed to drag this 1 percentage point below the historical average. Companies are less stretched today by debt than they typically are.

And they're also sitting on substantial cash buffers — at 29.4% of total financial liabilities.

As a whole, India's corporate debt-to-GDP ratio stands at just 51.1%. That might look like a lot in isolation, but it’s much lower than our peers. China, for context, is above 160%. Japan’s over 100%, Our corporate debt, if anything, is low.

There is one dark cloud on the horizon, though: trade policy uncertainty. We haven’t actually seen the worst of the protectionist impulses that are rising across the world. Those could easily push corporate margins down. In fact, companies are already lowering their profit estimates.

But that said: Corporate India enters 2025 with clean balance sheets, manageable debt levels, and healthy cash positions. If there’s global turbulence ahead, we couldn’t ask for a better place to start from.

The household debt story

That’s for our companies. We now turn to our households — something we’ve spoken about before, that remains extremely important.

Let's begin by putting things in perspective. India's household debt stands at 41.9% of GDP as of December 2024. Now, before you panic, consider this: the average for emerging market economies is 46.6%. We're actually well below average.

But the fact remains: that number is rising. Individual borrower debt, too, has grown in the recent past — from ₹3.9 lakh in March 2023 to ₹4.8 lakh in March 2025.

But that isn’t necessarily bad news. This increase has been mainly driven by higher-rated borrowers. 69.4% of India’s household debt is held by borrowers rated prime and above — people with strong credit scores and repayment capacity. These better-rated customers are growing, both in number, and how much they borrow. So, while debt is increasing, it's going to people who can handle it.

What about lower-rated and more leveraged borrowers?

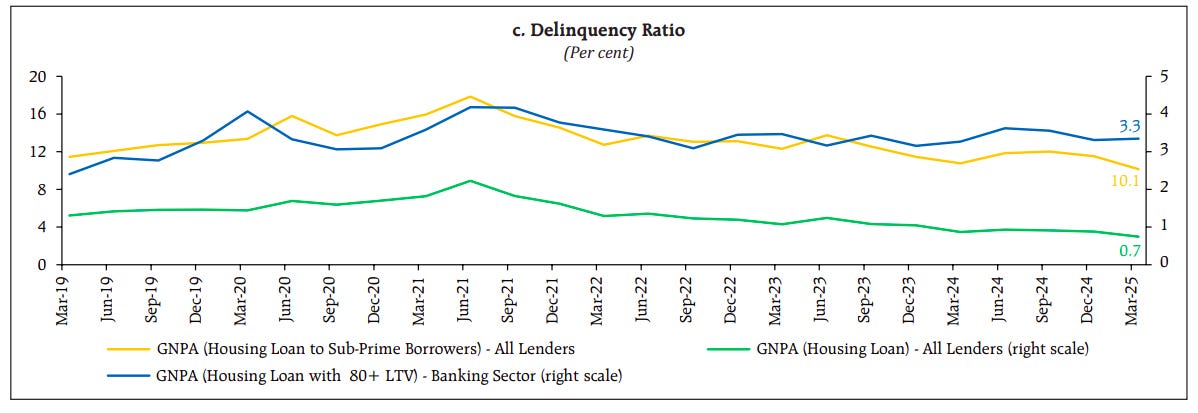

There’s no doubt — they are missing their loan payments. However, their delinquency levels have declined considerably from their COVID-19 peaks. During the pandemic, 16% of housing loans to subprime borrowers would turn into NPAs. That has dropped to 10.1% recently. In fact, for ‘high-LTV loans’ — where someone buys something largely on debt, putting very little of their own money in — it has dropped to just 3.3%.

But the story isn’t altogether rosy. There are genuine pockets of stress — especially when you look at housing loans.

While overall housing loan growth has been steady overall, more than a third of new housing loans in March 2025 went to existing borrowers taking additional loans. The share of housing loan accounts with loan-to-value ratios above 70% is also rising to 23.4%.

Basically, there are a lot of people who took loans to buy houses, and are finding it hard to pay them back. They’re having to roll their loans over, and are less able to put in their own equity.

But the real stress point worth watching is in the microfinance sector. This is where you see the worst of Indians’ indebtedness. Stressed assets — loans that have been overdue for more than a month, though less than half a year — jumped from 4.3% in September 2024 to 6.2% in March 2025. This isn’t merely because people have too much debt on their hands. The share of borrowers with loans from three or more lenders is declining, which indicates that people aren’t just stretching themselves thin. They’re just finding it hard to repay their loans.

So, does India’s household debt growth represent dangerous over-leveraging? Or is it just healthy credit growth? The evidence suggests it's more the latter than the former, but there are specific pockets of stress that one needs to keep a sharp eye on.

How Indian Families Are Changing Their Money

There’s another interesting story the FSR report tells: Indian households are reshaping their approach to wealth building.

The financial wealth of India’s households grew sharply in FY24. About 30.9% of that growth came from asset price gains — essentially the price of shares and other financial assets going up. The remaining 69.1% came from actual financial savings. While Indians are saving more on one hand, they're also seeing their existing investments grow.

But here's what’s interesting: the make-up of Indian household wealth is shifting dramatically.

As recently as March 2019 — barely five years ago — Indian households were rather conservative in how they allocated their money: 46.3% in deposits, and another 28.6% in insurance and pension funds. Just 15.7% would go to equity and investment funds. 8.6% was in currency, and a tiny 0.8% in debt securities.

Fast-forward to March 2024, and something remarkable has happened.

Deposits and insurance/pension funds still dominate, at nearly 70% of household financial wealth. But interestingly, the share of equity and investment funds has surged to 22.4% — a jump of almost 7% in just five years.

Think about what this means. Despite deposits still being the preferred choice at 40.6% of financial assets, Indians are learning to invest. They’re increasingly comfortable putting their money into the capital markets. Equity and investment fund allocation has grown from less than one-sixth to more than one-fifth of household financial wealth. At Zerodha, we’ve had ring-side seats to this once-in-a-generation shift, and it’s been every bit as dramatic as the numbers suggest. We’ve talked about this in great detail on another blog.

This hasn’t come at the cost of stable investments. At 28.8% of financial assets, this segment has remained stable. Indians aren't reducing their focus on protection and retirement planning – they're adding growth investments to this safety net.

Then what are they cutting back on? Cash is one answer. Currency holdings have decreased slightly from 8.6% to 7.6%. People are moving cash into productive assets rather than keeping it idle.

The RBI has been worried about this shift. We’ve discussed how the RBI has flagged the slow pace of deposit creation many times before. But the numbers suggest that his shift is happening alongside the deposit story, not instead of it. The absolute amount in deposits is still growing – it's just that the growth in equity investments is outpacing everything else.

One again: Indians aren't abandoning safety; they're adding growth to their portfolios.

That is creating a visible shift in the markets. Domestic institutional investors — mutual funds, insurance companies, and banks — now own 18.1% of NSE-listed companies. For the first time in our recent economic history, they’ve surpassed foreign portfolio investors — who hold 17.5%.

What's driving this generational surge? Several factors are at play.

First, the digitisation of investing has made equity markets more accessible than ever. The rise of mutual fund SIPs, direct equity investing through apps, and improved financial literacy are making it much easier for Indians to get to the markets.

Second, there's a shift across generations. Younger Indians have grown up seeing consistent equity market returns over decades, and are now more comfortable with market-linked investments than their parents were.

Third, inflation concerns are pushing people to look beyond traditional deposits for returns. When the returns on deposits struggle to keep pace with inflation, equity investments increasingly feel necessary for wealth preservation, not just wealth creation.

Whenever there's been market volatility off late — and we've seen plenty — domestic institutional investors and individual investors have provided crucial support to Indian markets, helping preserve stability even when foreign investors sell. This resilience is a new and important characteristic of Indian financial markets.

The positives are clear: as Indian companies grow and markets expand, household wealth grows with them. On the other hand, Indians are more vulnerable to the ups and downs of the market than they’ve ever been.

The Bottom Line

So, what does all of this tell us about India's financial health as we move through 2025?

Corporate India appears to be in robust health. While uncertainties loom, they’re entering this time on a solid foundation. On the household side, we're seeing a slightly more nuanced picture than the debt scare stories suggest. Yes, household debt is growing, but it's largely driven by credit expansion to creditworthy borrowers rather than dangerous over-leveraging. The pockets of stress are real, but they’re also contained.

We're also witnessing a fundamental shift in how Indian families approach wealth building, moving toward market-linked investments while maintaining their commitment to safety.

The overall picture? The Indian financial system is maturing. As financial health-checks go, this is a surprisingly positive one.

Tidbits

We covered when the global sensation weight loss drugs first came to India and we have an update on it.

Demand for weight-loss drugs in India has surged, with Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro doubling June sales to nearly ₹260 crore and Novo Nordisk’s newly launched Wegovy entering the market. Rising obesity and diabetes are fueling a fivefold growth in India’s obesity drug market since 2021, turning it into a key battleground for global pharmaceutical giants.

(Source)We looked at the hotel businesses recently and what their long term plans were. Another hotel company has come out with a new plan to expand.

At its AGM, IHCL Chairman announced a nearly ₹6,000 crore investment over five years to double the company’s portfolio to 700 hotels and 70,000 rooms by FY 2030. The expansion will include strategic acquisitions of boutique hotel chains—like Tree of Life—and a shift to a 50:50 mix of owned and managed properties.

(Source)We write about hospital chains and how their results pan out every other quarter. A recent announcement might shake up how our next story looks.

Aster DM Healthcare plans to overtake Apollo Hospitals as India’s top hospital chain by adding 3,300 beds and expanding into smaller cities like Indore and Bhubaneswar. Following its merger with Blackstone’s Quality Care India, Aster aims to boost margins and scale up to 13,600 beds within five years.

(Source)We looked at de-dollarization, a concept which causes a stir in financial circles around the world. This recent data raises the question on whether it is just an abstract concept or a real possibility.

Indian companies are cutting back on borrowing in US dollars, as dollar borrowings have plunged from over US $11 billion in March to just about US $2.9 billion in April.This signals a shift towards rupee-based funding, driven by lower global appetite for risk and rising faith in India's economic stability.

(Source)Every single publication and their mother covered the Jane Street news last week and we are no exception. And there’s an update.

Jane Street is pushing back against SEBI after being barred and told to return over $570 million, accused of manipulating bank stock options. The firm insists its trades followed standard arbitrage practices and says it adjusted strategies when exchanges voiced concerns.

(Source)We shared a story on the colossal mess of Pakistan’s solar revolution yesterday and got some comments on how something similar is happening in Kerala. Here’s a sneak peak into that.

The new draft power rules in Kerala are in discussion and are facing backlash because they propose changes to net metering policies that would reduce the financial benefits for rooftop solar users. Critics argue that these changes favor large power producers over individual solar panel owners, potentially discouraging small-scale renewable energy adoption.

(Source)

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Mridula and Bhuvan.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Suggestion to not use AI generated Image, It makes the information look cheap.