All you need to know about ports

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How do ports actually work?

Why telcos are unhappy with TRAI’s new tariff caps

How do ports actually work?

Recently, we decided to dive into the ports sector. We initially thought we’d just do a simple breakdown of major Indian port stocks — but to tell you the truth, there was just too much context to how the sector works, and we just had to get all of that out of the way first.

So we’re going to do this in two parts. In one of our coming editions, we’d look at India’s major port stocks, and how their businesses have been running. Before that, though, you should just know what those companies really do.

Most people don’t really think about ports — at least not unless they’re geeks like us, or are constantly glued to the markets. To most, ports are just a place for ships to park. People have a vague imagination of what they are: maybe a bunch of ships, a few cranes, and lego-like stacks of containers.

But that isn’t nearly all that they are: make no mistake, ports are remarkable operations. They’re the invisible backbone of the global economy. Every single item you see around you — your laptop, your phone, the chair you’re sitting on, even the food you order — all of it has probably touched a port at some point. They’re the lungs of any economy.

We mean that. Ports are critical infrastructure. They’re gateways into any economy; they set the rate for how fast goods can enter or leave a country. Consider this: 70% of India’s trade by value, and about 95% by volume flows through our ports. The story of our ports, then, is the story of our economy.

That’s why we wanted to figure out how they work, who controls them, and how money is made — or lost — across this system. We’ll start at the very beginning and walk through every layer of this ecosystem. As always, we’re just learning about all this ourselves. If we’ve missed something, or if you have something to add, let us know in the comments!

The origin story: from Harappan docks to modern PPPs

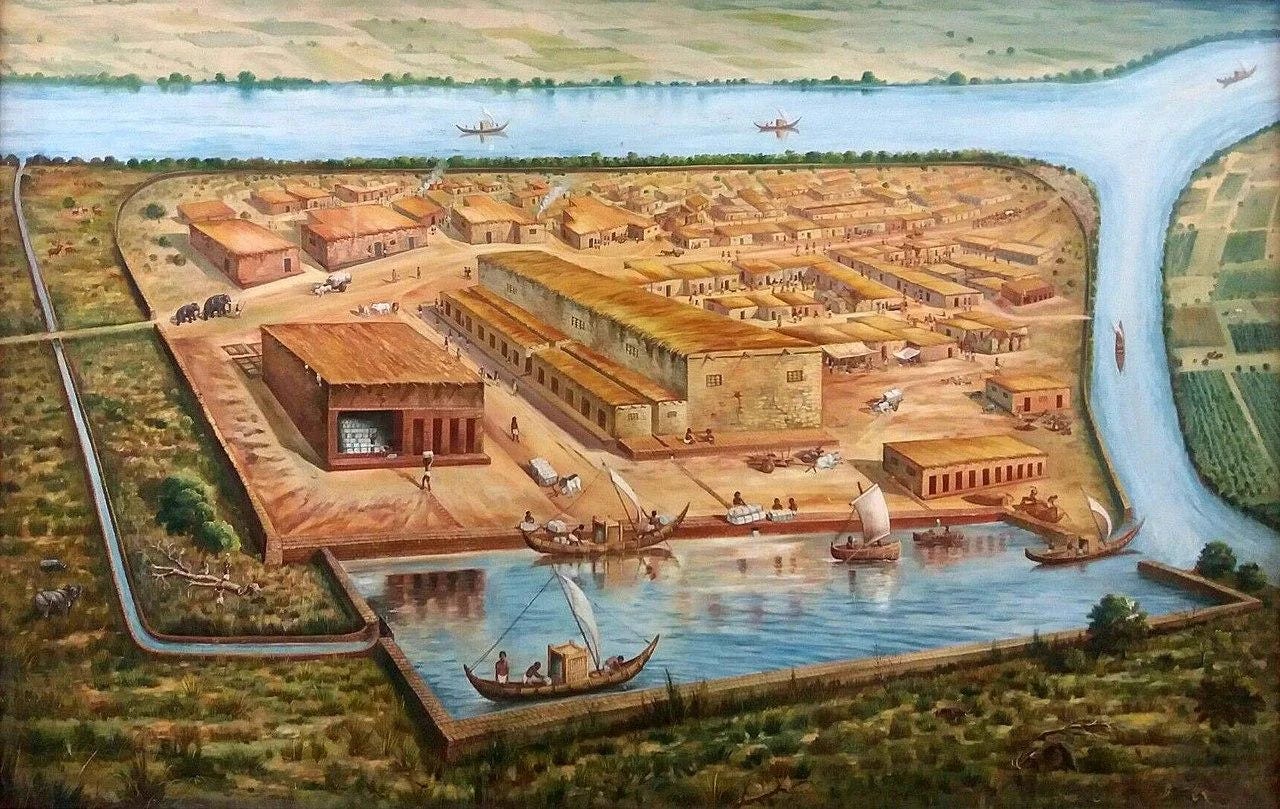

India has been a maritime trade hub for millennia.

We have had ports for almost as long as there have been humans on the subcontinent. The Indus Valley civilization, for instance, built one of the world’s first dockyards at Lothal (around 2400 BCE) — near modern-day Ahmedabad.

For centuries, then, we sat at the heart of a flourishing maritime network — the “Maritime Silk Road” — that ran all the way from Eastern Africa to South-east Asia.

Fast-forward to colonial times. The British were fundamentally a naval power, and when they came to India, they organised themselves around three key ports — in Mumbai, Kolkata, and Chennai. These colonial ports were placed under what became known as ‘Port Trusts’, and they were fully state-run. The the colonial administration owned and operated every part of those establishments: the land, the berths, the cranes, the labour.

These set the foundation of what was called the ‘Service Port Model’ — a set up where ports were entirely the responsibility of the government. This was a model worked when volumes were small, trade was limited, and shipping lines were few. But when globalisation took hold, the world changed.

By the late 20th century, global trade had exploded. India liberalised as well, and slowly joined this churn. Meanwhile, the world was finding innovative new ways of making trade as efficient as possible. Ideas like ‘containerisation’ were becoming the global default for how goods would be handled.

India needed a strong push towards modernisation. The old model simply couldn’t keep up with the pace of this change. It lacked speed, capital, and equipment. And so, India — like many other countries before it — moved to what’s called the ‘Landlord Port Model’.

In this new model, the port authority — usually the government — continued to own land and basic marine infrastructure. But the “terminals” themselves, i.e. the spots where ships actually docked, were now leased out to private operators for long concessions, typically for thirty years. These private players could then invest their own money into whatever the terminal needed: cranes, yards, gates, IT systems, manpower etc., and run the terminal like a business. For this, they’d either pay the port authority a share of their revenue, or a fixed rent.

Until 2021, this shift was ad hoc. In theory, ports were still governed by an old 1963 law, under which major ports were legally required to function under the old state-centric model. In 2021, though, the move towards privatisation was formalised. The government passed what’s called the ‘Major Port Authorities Act, 2021’, which replaced the 1963 law.

This new act formally allowed port trusts to behave more like independent commercial landlords. They had more financial autonomy, the ability to form boards with external professionals, raise capital, and make operational decisions faster.

Since then, major ports — like Navi Mumbai’s JNPT — have completed their transition to the Landlord Model. Today, every container terminal at JNPT is privately operated. The port authority itself no longer manages terminals directly. It’s simply the port’s landlord.

Parsing through port-speak

It’s possible that some of this went over your head. It went above ours when we began this piece. The port industry seems to have its own language. It’s only when you understand this lexicon does anything else click.

Ports

Let’s start with the word “port” itself.

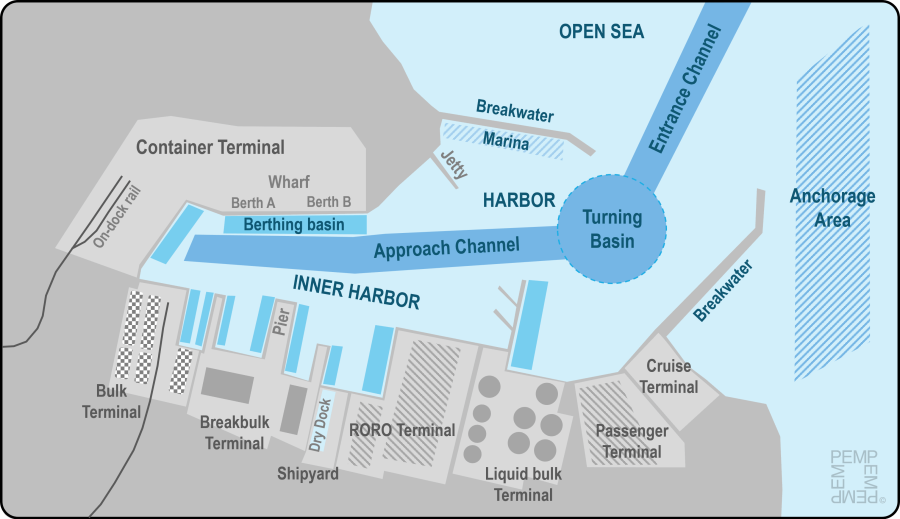

A port isn’t just merely a spot of land where a ship docks; it’s a massive, heavily-engineered complex. It’s essentially a small, cordoned-off portion of the sea. Ports usually have “breakwaters” that close them off the waves and activity outside, with an ‘approach channel’ from where ships could enter. Once ships enter a port, they’re tied to berths or quays. Beyond that is a mass of infrastructure on the shore — roads, rail lines, customs buildings, warehouses, and even power stations.

India has two types of ports: major ports and non-major ports. This isn’t a distinction based on size, though, but on history.

We have 12 ‘major’ ports — in Mumbai, Chennai, Visakhapatnam, Paradip, Kolkata, etc. These are governed by the central government. Historically, these were all service ports, though they’re now all shifting to the landlord model.

Then, we have over 200 “non-major” ports, which are governed by state maritime boards or port departments. Don’t let the name fool you — a port doesn’t have to be “major” to be massive. For instance, Mundra Port, India’s busiest port by volume, is a non-major port.

Most private port developers in the port business run “non-major” ports. Adani Ports is the biggest of these, with 12 ports across the country, including massive establishments like the ports in Mundra and Krishnapatnam.

Then there’s JSW Infrastructure. When they started out, this was a small enterprise, building the infrastructure the group needed to import coal for JSW Energy and export steel for JSW Steel. Over time, though, it has pivoted into a massive third-party logistics business, with a lot of its cargo coming from outside the JSW group.

We’ll break both their Q4 results down in a future edition.

Terminals

Ports usually have multiple terminals.

Each of these is like a self-contained industrial park. A terminal comes with its own equipment, people, and software systems — all of which is specific to the needs of that terminal. One terminal might just handle containers. Another might only handle coal. A third might handle cars, while another might deal with crude oil. For instance, Gujarat’s Mundra Port — India’s largest port — has specific terminals for everything from containers, to crude oil, to agri-commodities.

Functionally, terminals work like independent operational entities, even though they’re of inside the same port boundary. They might share the water and access channels, but the way each terminal handles its cargo is completely different.

And so, as you might imagine, running a terminal is a full-time business of its own. Many companies — like DP World, PSA and APM Terminals — have built entire businesses around terminal operations: bidding for and running specific berths inside public ports.

Cargo

When people think of ‘cargo’ (if they ever do), they’re usually just thinking about containers. But that’s only part of the story.

In fact, speaking broadly, there are five types of cargo:

Dry Bulk: There are commodities like coal, iron ore or cement, which are usually transported loose. They’re poured directly into the ship’s hold — no packaging, no containers.

Liquid Bulk: Like dry bulk, liquid commodities like crude oil or chemicals aren’t packaged separately either. Instead, these are pumped into specialised tankers through pipelines. As you might imagine, terminals that handle liquid bulk need specialised equipment for this: like tank farms, safety systems, and pressure-regulated infrastructure.

Containerized Cargo: This is the sort of cargo that’s stored in the huge, lego-like 20- or 40-foot steel boxes you see on ships. These carry everything from electronics, to auto parts, to toys. Our era of global trade is arguably only possible because of these standardised steel boxes.

Break-Bulk: Items that are oversized or ‘non-containerizable’ — like turbines or construction equipment — need to be placed individually on ships. This is a difficult, time-consuming process: these are lifted individually onto ships using cranes and slings, and require special stowage plans to ensure that everything stays safe.

Ro-Ro (Roll-on/Roll-off): Wheeled cargo — like cars or buses — can simply be driven directly on and off the ship.

Each of these is a different business altogether. Each has its own economics, and needs a different kind of terminal. For instance, where bulk cargo terminals usually earn by weight, container terminals may earn according to the twenty-foot equivalent units they transport. The margins, too, could vary. Bulk terminals run a volume game. Liquid terminals service long-term customers, like refineries. And so on.

Most of India’s port traffic, still, is bulk. In fact, nearly a third of our cargo is just crude oil and petroleum. Add coal, iron ore, and fertilizers, and you’re looking at over half of total volume.

The iconic container-based ships, however, are rising quickly.

When containers first emerged onto the scene, they revolutionised global trade. Before containers, cargo had to be loaded onto ships box by box, bag by bag. It took days. With containers, very specific, non-commoditised goods could be packed in a standard fashion. They could move from truck to ship to train without being opened.

How a Steel Box Changed the World: A Brief History of Shipping

Containers usually carry high-value, manufactured goods — so the amount of cargo we carry, in a sense, is a good proxy for how complex our economy is. As of 2024, containers account for around a quarter of India’s total port volume by weight, but a much larger share by value.

Location, location, location

Ports don’t exist in a vacuum. They’re built as gateways to everything that’s on the land nearby. And so, the location of a port means everything.

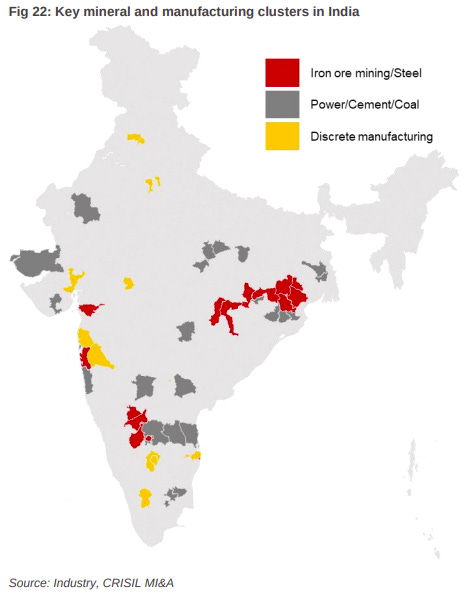

India’s coastline, of course, has two very distinct halves: the eastern coast, and the western coast.

Our western coast has many natural advantages. The coastline is straighter and deeper. This side is also closer to the main global shipping lanes to Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.

Gujarat alone has over a dozen ports — both major and private — and the state singularly accounts for over 40% of India’s total cargo throughput. Gujarat’s key ports, like Mundra or Pipavav, have slowly turned into massive logistics hubs. But we also have major ports in Maharashtra (JNPT), Goa (Mormugao) and Karnataka (New Mangalore). These are linked to major industrial belts through strong road and rail networks.

Our eastern ports, meanwhile, serve our mineral-rich belt of Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Jharkhand — home to coal, iron ore, and bauxite. And so, Eastern ports like Paradip are bulk cargo powerhouses. As you move south-wards, however, the ports are increasingly oriented towards more sophisticated cargo. Andhra Pradesh, for instance, is investing aggressively in both bulk and containerized cargo ports. Tamil Nadu, too, has a series of ports that support its industrial hubs.

Unlike the western side, our east coast currently faces major challenges. The coastline is more prone to cyclones. Eastern ports also tend to silt up, and require constant dredging. Connectivity, too, has historically been weaker, especially in West Bengal and Odisha. But that might be changing. The eastern coast is seeing considerable investment — into everything from connectivity to deeper ports.

Are our ports good enough?

We’ll end this piece with one final idea: transshipment.

India’s ports have serious legacy issues. They aren’t deep enough to service large, modern cargo ships. And so, many of India’s containers are not moved directly from Indian ports to international destinations. They first go to foreign hubs like Colombo, Singapore, or Port Klang, and are then shipped forward.

This adds time and cost to both our imports and exports. It puts Indian businesses at a disadvantage against our major competitors. To counter this, India is building its own deep-draft transshipment hubs like Vizhinjam in Kerala and Galathea Bay in the Andamans.

That will be the next chapter in the evolution of Indian ports.

There are many other threads that we’ve deliberately kept out of this primer. But consider this as just the first chapter. In the days to come, we’ll dig into many other aspects of this fascinating business. Stay tuned!

Why telcos are unhappy with TRAI’s new tariff caps

India’s telecom regulator, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI), recently issued a new rule: in essence, it capped certain internet rates. None of our big telecom operators are happy with the move.

But here’s the thing: this cap does not apply to your regular mobile data or home broadband bills. In fact, it probably has nothing to do with any of the services you’re even familiar with. It just targets the rates that public Wi-Fi providers pay for connectivity under the government’s PM-WANI Wi-Fi scheme — something that merely benefits 3 lakh customers. But don’t let that fool you: this move could fundamentally change how Indians access the internet.

So what’s happening? What is this cap trying to target, and why was it needed in the first place?

Let’s break it all down.

What even is PM-WANI?

‘PM-WANI’ stands for Prime Minister’s Wi-Fi Access Network Interface — a government initiative launched in 2020 to expand public Wi-Fi access across India.

The scheme was a big bet on public wifi. While mobile data is popular, the government realized that many people still lack affordable, high-speed internet access. Meanwhile, mobile networks get congested, and some areas have bad coverage.

Public Wi-Fi hotspots could plug these gaps. It could complement mobile networks by providing cheap internet exactly where connectivity is limited or expensive. It was to be a final push to bridge the digital divide – to bring the internet to anyone that still couldn’t reach it, without relying on an expensive mobile plan or home connection.

To do so, the government planned to help people set up millions of Wi-Fi hotspots nationwide. This would give people — especially those in rural and underserved areas — access to cheap (or even free) internet in public places. Places like railway stations, village markets, or libraries could double up as places where anyone could get to the internet.

Now, the government didn’t actually build out all the infrastructure for this. It merely saw itself as an enabler, with the limited role of creating a framework and providing the technological backbone for the project. The actual set-up, it hoped, would be built out by the private sector under this framework. This reliance, perhaps, was the scheme’s downfall. While the scheme set ambitious goals for itself — 10 million public Wi-Fi hotspots by 2022, and 50 million by 2030 — it didn’t even come close. As of June 2025, ~3.33 lakh PM-WANI hotspots have actually been deployed. That’s a fraction of the original target.

Before we tell you why it didn’t pan out, though, you should know how the program was supposed to work.

How does PM-WANI work?

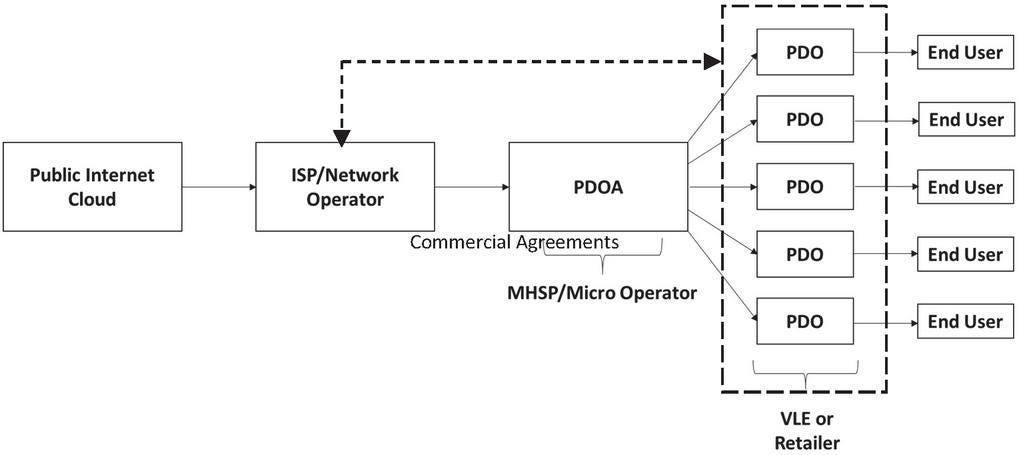

The PM-WANI system broke the task of providing Wi-Fi into different roles:

Public Data Office (PDO): This is the actual Wi-Fi hotspot provider. This could be anyone — a small business, like your neighborhood cafe, kirana store, or chaiwala — or even an individual who sets up a Wi-Fi access point for public use. These would basically “host” the Wi-Fi and serve internet to users around them.

Public Data Office Aggregator (PDOA): Behind these frontline PDOs is an “aggregator” — the PDOA. These would provide a cloud-based platform underlying this Wi-Fi access. Their platform would handle everything from authenticating users, to generating data coupons, to collecting payments.

Telecom Operators (Telcos/ISPs): The internet service providers you’re familiar with — like BSNL, Jio, Airtel, etc. — would supply the actual internet bandwidth, called “backhaul” in telco lingo. We had covered this in depth sometime back on The Daily Brief. Telcos essentially created a data pipeline — they were the ones selling connectivity to the PDOs. In the PM-WANI model, they would essentially supply connectivity on a wholesale basis to last-mile providers.

While internet rates under PM-WANI could vary a lot, typically, it would be well below what telecom companies charge. A 5GB data pack on PM-WANI, in many places, would cost just ₹18. The same 5GB from Airtel would set you back ₹77, while Jio charges ₹69 for 6GB. That’s a big gap — and exactly the kind of affordability PM-WANI is trying to bring to the table.

While we often talk about regulatory issues on The Daily Brief, this is one place where the government was actually trying to get out of the way. In fact, it made it fairly easy to become a PDO. One didn’t need a license or permit to offer PM-WANI Wi-Fi, and there were no registration fees. This low barrier to entry was meant to encourage small entrepreneurs to participate and roll out Wi-Fi in their communities.

But if this new system was cheaper and had low entry barriers, why didn’t it actually take off?

Why hasn’t PM-WANI taken off yet?

The short answer: cost and practicality.

While setting up a Wi-Fi hotspot doesn’t require a license, a PDO still needs an internet connection from a telecom operator. And those connections have been way too expensive for small providers. According to TRAI. the steep prices telcos charged to PDOs have been the biggest barrier to the scheme’s growth.

Here’s the crux of the problem: Telecom companies usually have different classes of internet plans. Here’s a quick explainer:

Home Broadband (Retail FTTH): This is the kind of connection you get at home – for example, a fiber-to-the-home plan. Importantly, it’s sold under the assumption that you’re using it for personal or family use.

Commercial Broadband: This is essentially the business version of a broadband plan. It might be similar to home broadband in speed, but it usually costs much more. After all, businesses need reliable service and better customer support, and beyond that, the telco simply charges a premium because it knows that a business can pay more. Telcos expect anyone using a connection for commercial purposes to take these pricier plans.

Internet Leased Line (ILL): This is a top-tier dedicated internet connection, typically used by large enterprises, hotels, or colleges. An ILL is like a private highway for your data – you don’t share bandwidth with other users, and you often get symmetrical speeds (equal upload and download) with a strong service guarantee. This, of course, is very expensive — often costing tens of thousands of rupees a month.

Imagine you ran a small shop that tried to become a PDO. You couldn’t just buy a normal home broadband plan to use for their public Wi-Fi — telcos forbid, or at least discourage this. Instead, telecom firms consider providing public Wi-Fi as a “commercial” activity, and would push you to sign up for much costlier business plans — which could cost tens of thousands of Rupees a year.

In fact, in many cases, operators insisted that you could only take a leased line, and not a regular home/office broadband, if you were trying to set up a PDO hotspot. This could push your bills into lakhs of Rupees. In fact, some operators were reportedly charging up to ₹8 lakh per year (over ₹65,000 per month) for the connections needed by PDOs.

Ideally, such commercial plans would cater to larger, richer businesses — the sorts that generally work heavily with the internet — like entire office buildings. That wasn’t the target group for PDOs at all. Becoming a PDO was supposed to create an additional income stream for small shops and cafes. But these high costs made it commercially unviable to do so. There’s simply no way a small chaiwala or kirana store can pay ₹65k a month just to give Wi-Fi to customers – especially if the service was meant to be at dirt cheap rates.

This pricing mismatch meant that there were very few takers for the PDO model. As a result, PM-WANI stayed a niche pilot project in many places, falling drastically short of its targets.

The new TRAI tariff cap and what it means

TRAI is now trying to remove this bottleneck. Its new rule sets a cap on the rates telecom operators can charge those PDOs. It’s pretty straightforward: any wired broadband plan that a telco offers to regular households must also be offered to PDOs, at no more than double the retail price.

If you can get a 100 Mbps home fiber plan for ₹800 per month, the telco cannot charge a PDO more than ₹1,600 per month for a similar connection. This cap applies to all fiber-to-home plans up to 200 Mbps that operators provide. By capping the price at 2x the home rate, TRAI is trying to ensure that PDOs get access to reasonably priced bandwidth, instead of being forced onto ultra-costly enterprise plans.

To quote the Department of Telecommunication

“With this ceiling in place, the backhaul tariff for the Public WI Fi hotspot are expected to come down drastically and are set to become up to 10 times more economical.”

The move is aimed at making it financially feasible for small businesses to become PDOs and set up Wi-Fi hotspots. If the cost of connectivity comes down, shopkeepers and small businesses might finally see a business case (or at least a break-even case) for offering public Wi-Fi. The regulator hopes this will dramatically boost the number of Wi-Fi hotspots under PM-WANI.

To TRAI, this pricing framework will balance interests: it’ll keep connectivity affordable for small PDO entrepreneurs while still providing a fair payment to the service providers (the telcos) for their network. This is why it came up with a cap of twice the retail price – it’s higher than what a normal consumer pays, , giving telcos something extra for commercial use, but not so high as to be prohibitive.

Why telecom operators are unhappy

Of course, the big telecom operators — like Jio, Airtel, Vodafone-Idea, etc. — are displeased with this new rule.

From their perspective, the regulator is intervening in core commercial decisions like pricing, and eating away at their profits from business customers. Telcos argue that public Wi-Fi providers are basically piggybacking on the networks that they spent huge sums to build, without compensating them adequately.

Telcos also fear revenue loss. They worry that if many people start using Wi-Fi from PDOs, it might reduce the usage of mobile data packs that telcos sell directly. Why buy an expensive mobile data top-up if the shop next door offers Wi-Fi at throwaway rates? This could eat into the telecom companies’ data earnings.

During the consultation process, in fact, some telecom companies described PDOs as potential competitors to their business. One large operator pointed out that PDOs essentially buy bandwidth to resell it, eating into these operators’ turf. With TRAI’s latest rule, not only will they lose customers to these public hotspots, they’ll now be forced to sell that bandwidth to them at government-mandated prices.

To a telco, this looks like they’re essentially subsidising others to eat away at their business.

Of course, the other side of that argument is that many people are currently underserved by our telecom system. Not everyone has a good mobile data connection or enough data to meet their needs — and more connectivity options could give them a way of bridging that gap. The government and TRAI clearly decided that public Wi-Fi is still relevant for inclusivity and as an alternative access method. By capping the tariffs, TRAI essentially overruled the telcos’ complaints in favor of giving PM-WANI a fighting chance.

Will this rule boost public wi-fi – and what’s next?

TRAI’s hope is that with lower backhaul costs, many more small businesses will step up to become PDOs, leading to an explosion of Wi-Fi hotspots across India.

Here’s the optimistic case: more hotspots could mean better internet availability in places that currently have poor connectivity. This could serve as a final push in bringing the internet to everyone. Meanwhile, it could also help offload some demand from mobile networks. In congested city areas, in fact, this might even improve mobile network quality by shifting some usage to Wi-Fi.

But it’s important to be cautious and not oversell the outcome.

While the new tariff cap removes a major hurdle, it doesn’t automatically guarantee that PM-WANI will become a roaring success. There are still question marks. For one, the program will always lag broadband infrastructure. If a home broadband plan isn’t available or reliable in a certain village (since many rural areas still lack good broadband infrastructure to begin with), PM-WANI can’t reach there until basic broadband does.

So infrastructure rollout remains key. And telcos will only invest in that infrastructure if they think they’ll be compensated adequately for it. That’s a matter of whether this price cap is adequate — a question that’s far beyond what we can answer.

There are many other, smaller questions. Will telecom operators wholeheartedly cooperate and provide their home broadband plans to PDOs at the capped rates without other strings attached? Will small shopkeepers actually take the initiative to install and maintain Wi-Fi hotspots? Would a price tag twice that of the retail price might be too high? We don’t know.

The tariff cap is a big step that removes the major financial roadblock for PM-WANI, but it’s not a magic wand. It will likely take months (or years) to see if the number of hotspots actually rises as a result.

Tidbits

DLF Clocks ₹11,000 Crore in One Week from Gurugram Luxury Project

Source: Reuters

Real estate giant DLF has recorded sales worth ₹11,000 crore in just one week from its new luxury residential project, Privana North, located in Gurugram. The project, comprising premium 4BHK apartments and penthouses, marks one of the highest-ever residential sales achievements in India. This performance comes close to DLF’s previous record of $1.4 billion in sales from The Dahlias. With this development, DLF continues to strengthen its position in the high-end housing market. The rapid scale of bookings reflects growing appetite for luxury real estate among affluent buyers. Privana North’s performance adds to the momentum DLF has built over the past year, further boosting its cash flow visibility.

Blackstone Acquires South City Mall in ₹3,250 Crore Deal, Marks Largest Retail Transaction in Eastern India

Source: Business Standard

Blackstone has acquired Kolkata’s South City Mall in a landmark ₹3,250 crore transaction, making it the biggest real estate deal ever in the region. The mall, spread over 1 million sq. ft., sees a daily footfall of 55,000–60,000, which can rise up to 2 lakh on weekends and festive days. With an annual turnover of ₹1,800 crore, it houses major global brands like Zara, Armani, and Adidas, along with a 1,400-seater food court and 10 restaurants. The deal includes additional unsold inventory from Sri Lanka’s luxury residential project “Altair,” taking the total transaction value to ₹3,400 crore. This acquisition adds to Blackstone’s expanding India retail portfolio, which also includes Select Citywalk and assets from the Prestige Group. The mall was developed by a consortium including Emami, Merlin, and Shrachi groups, who have now exited the asset.

TVS Motor Launches iQube Electric Scooter in Indonesia at IDR 29.9 Million

Source: Business Line

TVS Motor Company has entered the Indonesian electric two-wheeler market with the launch of its iQube electric scooter, priced at an introductory IDR 29.9 million (approximately ₹1.6 lakh). The scooters will be assembled locally at its East Karawang facility through its subsidiary PT TVS Motor. The iQube offers a real-world range of 115 km per charge, a top speed of 78 km/h. TVS has already reached a global customer base of over 6 lakh iQube units. According to the company, Indonesia’s electric two-wheeler segment has grown at a CAGR of 101% over the past three years. With bookings now open, TVS aims to tap into this fast-growing market, leveraging local assembly to gain pricing and logistical advantages. This marks the company’s first electric vehicle launch in the ASEAN region, highlighting its international growth ambitions.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Kashish.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Keep it up, 💪 It helps me a lot 💯.

guys these tidbits are from yesterday's newsletter.