A new front opens in the chip wars

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The battle for Nexperia

China’s $800 billion question

The battle for Nexperia

If you’re not paying attention, the geopolitical moves around chips might seem like a question of high-level technology, more to do with the future of AI or robotics than our regular, prosaic concerns.

The reality, though, is that chips are everywhere.

Consider your car. You probably know that your car has large, sophisticated electronic systems, with chips controlling everything from how you accelerate, to how you brake, to your headlights or air conditioning. But beyond these, there are thousands of tiny chips scattered all the way through — often the size of a grain of sand. They carry out boring tasks — like ensuring that electricity moves in the right direction, or that voltage spikes don’t fry your systems, or that signals don’t start mixing with one another. Together, they form the “connective tissue” that keeps your car running smoothly in a brutal environment of heat, vibration, and electric shocks.

On paper, these components are mundane and low-cost — a far cry from the near-magical processors that so often feature at the heart of the global chip war. Many of them cost less than ten rupees a piece. But as we’re quickly learning, those, too, can create a temporary worldwide chokehold.

The world’s automotive industry — and many others besides — has just been slammed by a crisis in these chips. Nexperia, the world’s leading manufacturer of basic chips, has become a subject of a global tussle between China and the West. This could well become the industry’s worst chip crisis since the COVID-era shortages.

And more broadly, it could signal the opening of a new front in the world’s chip war.

The invisible giant, and how it came under Chinese control

Nexperia began its life as a unit of Philips — the consumer electronics giant that makes everything from air purifiers to hair trimmers.

Philips was interested in computation well before chips existed. Back in the 1920s, it acquired the vacuum tube manufacturer, Mullard, back when the technology went into the back-end of radio broadcasting. This arm would accumulate experience for decades, making its way through many whole cycles of progress in computing technology. Eventually, in 2006, Phillips spun this arm off as ‘NXP Semiconductors’ — with most of its shareholding coming under the control of private equity investors.

The newly formed NXP was already one of the world’s largest semiconductor companies. And it was a complex company, with a variety of interests across industries. Along with Sony, for instance, it invented ‘NFC’ technology — what’s behind all sorts of “tap” applications, from metro smartcards to credit card payments. One of its trustiest sources of revenue, though, came from bulk sales of standard, low-grade chips that were the building block of all sorts of electronic systems.

In 2017, NXP divested this bulk business, spinning it off as Nexperia. It was immediately snapped up by a consortium of Chinese investors — led by Beijing Jianguang Asset Management Co., which was under Chinese government control. After some restructuring, Nexperia would eventually come to be controlled by Shanghai-based Wingtech technology, which is also partially controlled by the Chinese state.

Through all this, however, Nexperia maintained its European roots — with its headquarters still in Amsterdam. That fact is at the heart of the current controversy.

What’s at stake

Nexperia doesn’t make flashy, cutting edge chips. It makes standardised “legacy” workhorses.

Its portfolio extends to over 6,000 distinct products. For instance, Nexperia makes an estimated 40% of the world’s “discretes” — components like diodes or transistors, that perform a single function — like keeping electricity flowing one way, or amplifying signals. It also makes “MOSFETS,” extremely efficient transistors that can run thousands of times a second, and basic logic circuits, like AND, OR and NOT gates, which are at the heart of all computation.

Now, none of these are particularly cutting edge. We’ve known how to make them for decades, and the processes behind doing so are reasonably well-understood. Nexperia’s moat, though, is its sheer scale. It supposedly ships over 110 billion of them a year.

To create a modern car, you need hundreds of the sorts of components Nexperia makes. And for many of these applications, Nexperia’s products are considered the default. But market leadership, alone, doesn’t make it a chokepoint. Nexperia has many competitors, and many of them have the raw capacity to jump in. The real problem, though, comes from how the whole industry isn’t designed to handle a disruption.

See, cars are dangerous machines under perfect conditions. Failing components are simply not an option. And so, the automotive industry is wedded to ensuring quality and reliability — with long, stringent protocols around everything. The electronic components going into a car, for instance, must meet stringent standards like AEC-Q100/Q101. To get such a certification, one needs to get through a long battery of tests, which individually evaluate the facility where a chip is fabricated, the assembly unit where it is put together, and the exact process flow involved all across. These tests take two-three months to complete. Change any of this, and you need to be tested and validated all over again — even if what you’re making is absolutely identical, using the very same machines.

And that’s just the first step. The same process then cascades all through the supply chain. A component manufacturer that changes the source of its transistors shall have to re-engineer, re-test, and re-validate the component they produce. And then, an auto-maker must carry on their own vehicle-level validations. And so on.

These processes are slow by design. They’re meant to ensure that once a car hits the road, there are no surprises whatsoever. But that also kills the industry’s agility. If a major source of supply is disrupted, getting new supply online could take months.

The escalation

To understand the current crisis, you must first understand Nexperia’s global spread.

Nexperia is headquartered in the Netherlands, but controlled by the Chinese. The initial fabrication of its chips happens in Germany and the UK. But those are then shipped to locations across Asia, where they’re put together, tested and packaged. A lion’s share of that happens in its gigantic, 80,000 sq. m. factory in Guangdong, China.

This global footprint, not too long ago, was par for the course for most major manufacturers across the world. But now, those countries are all threatening to pull the company apart.

Nexperia has been on the radar of Western governments for a few years. In 2022, the UK government forced it to undo its acquisition of a facility in Newport, Wales, citing national security concerns. Then, in late 2024, the American government put its parent company, Wingtech Technologies, Nexperia’s parent company, on its “Entity List” — cutting its access to cutting edge technology.

Late last month, however, things took a sudden turn for the worse. On September 30, the Dutch government invoked a rarely used Cold War-era legislation, the ‘Goods Availability Act’, to forcibly take control of the company from its Chinese owners — claiming that there were “serious governance shortcomings” at the company. The very next day, the company’s CEO, Zhang Xuezheng, was removed from the company.

It isn’t clear why it did so. There are all sorts of explanations in the media — from US pressure to speculation that the company was transferring key technology from Europe to China. In an official statement, the Dutch government claimed that it was ensuring that Europe wouldn’t suddenly be cut off from access to Nexperia’s chips. Either way, the move practically moved the company into the hands of the Dutch government.

But whether or not Nexperia was controlled by China, most of its products would have to go through its China factory. And that became a vital chokepoint.

On October 4, China retaliated with sanctions of its own. Its Ministry of Commerce ordered that Nexperia’s subsidiaries and contractors were prohibited from exporting several key components abroad. In doing so, it effectively cut Nexperia’s China plants off its global supply chain. On October 10, Nexperia wrote to its clients, essentially saying that it could no longer guarantee delivery of its chips.

In the days since, an open mutiny seems to have broken out within the company. In a recent statement, Nexperia China claimed to be an independent entity, and told its employees not to follow any instructions from its Dutch headquarters. Managers, the instructions claimed, had a “right to reject” any instructions they received from outside China.

Can the Dutch reclaim its unit from the Chinese? Can the Chinese claw back the company from the Dutch? We don’t yet know for sure.

How bad can things get?

The worst part of the problem, perhaps, is that it’s hard to know who is impacted, and by how much.

Auto supply chains, as we’ve written before, are extremely complicated. No auto-maker builds a car from scratch. They all rely on huge networks of suppliers for components, who rely on their own suppliers, and so on. When Toyota tried to map the components that went into its cars, it found over 400,000 items that it was buying, from chains that ran as many as ten layers deep.

In fact, no single auto company could tell you exactly where they get all their components from. Nor, for that matter, could their primary suppliers. Car-makers must now trace every Nexperia component they use across thousands of parts — a formidable challenge. Companies like Volkswagen have set up entire task forces just to understand what a development like this means for them. India’s auto-makers face exactly the same problems.

If it is exposed to Nexperia, there’s little that a company can do other than wait — at least in the short term. Once their suppliers run out of stock, they could be forced to pause production outright. A Nexperia-shaped hole in one’s supply chains, after all, could take months if not years to patch. The last time there was a serious chip shortage, the world’s automotive industry is estimated to have lost $210 billion, with the production of 11.3 million vehicles getting stalled the world over. With chip-heavy electric vehicles gathering momentum in the years since, things could even be worse, this time around.

But that’s just one industry. More broadly, this opens new dimensions to the world-wide chip war. Often, the West has tried to outmaneuver China by cutting its access to cutting edge frontier technology. But it’s increasingly clear that there’s more than one way to play this game. The chip war isn’t just about advanced AI chips with sub-3 nm nodes — it could just as easily revolve around cheap, boring mass-market components embedded in everyday machines.

To India, though, this could also present a silver lining. This is precisely the sort of occurrence that strategies like “China+1” are meant to protect against. A short-while ago, we wrote about India’s baby steps towards creating a domestic chip industry — with major successes in creating domestic assembly plants, in particular. The tussle over Nexperia shows why, precisely, mastering this is important, even when it’s unglamorous. And it could bring even more urgency to such investments.

China’s $800 billion question

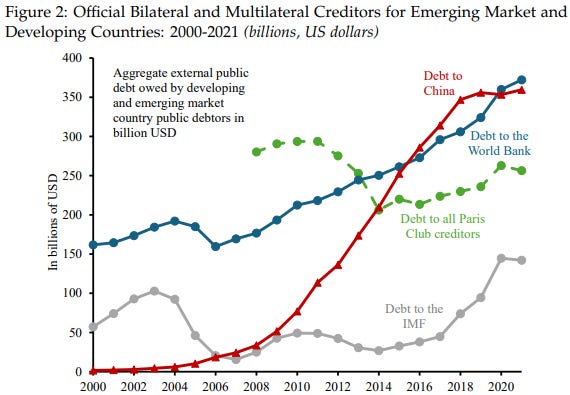

Over the past two decades, China quietly became the world’s largest government lender: giving out more than $800 billion in loans to developing countries. At its peak, China’s loan portfolio surpassed the World Bank, the IMF, and all 22 Paris Club creditor nations combined.

But, curiously, that lending boom has now reversed. And it could well spark a quiet debt crisis across the world.

To understand this better, we’re digging through new research by Sebastian Horn, Carmen Reinhart, and Christoph Trebesch — three economists who’ve spent years piecing together China’s debt puzzle. Theirs is a remarkable feat. For years, nobody even knew the full scale of Chinese lending. Unlike traditional lenders, China doesn’t publish data on who it lends to, how much, or on what terms. It practically treats its overseas lending as a state secret. In fact, many of its loans include confidentiality clauses that prohibit borrowers from disclosing the terms, or even the existence, of its debt.

This all but drew an iron curtain over China’s financing activity. By 2019, roughly half of China’s loans to developing countries were absent in the World Bank’s main debt database. Details of these loans have come in a slow trickle, often during crises. Since 2019, more than $600 billion in previously unrecorded loans have been added to official statistics.

So what were they hiding? That’s what we’re diving into.

Scale and scope

There’s a clear pattern to China’s lending: it targeted low and lower-middle income countries — many of them commodity exporters in Africa and Latin America. And it funneled massive amounts of credit to them. A country like Angola, for instance, owes China 29% of their GDP. Zambia owes 28%. Laos, 33%. The small but strategically located Djibouti, 36%.

Right at the mouth of the Red Sea

For these countries, China was filling a vital gap: the lack of willing private creditors. In low-income countries, private creditors make for just 6% of total external debt — compared to over 40% for upper-middle-income countries. While wealthier emerging markets like Brazil, Turkey or India could tap international bond markets for money, these countries couldn’t. They enjoy such little trust that the international capital markets are practically closed to them.

That’s where China came in. To them, China was the only option for financing. In 70% of the world’s low-income countries, debts to China now exceed what’s owed to all private creditors combined. China also dominates lending to 40% of lower-middle-income countries, and nearly one-fifth of upper-middle-income countries.

How China lends

But China doesn’t always lend like a regular lender.

On the surface, most Chinese loans look reasonably standard. They’re denominated in US dollars, and come with market-based interest rates — typically 250 basis points over LIBOR. They don’t look like the development finance that Western countries offer. But they resemble regular commercial loans, with a healthy risk premium.

Only, there are major differences in the fine print.

For one, around half of China’s loans are collateralized. That is, in exchange for the loan, the borrower commits to routing foreign currency proceeds from commodity sales — often oil — into offshore bank accounts controlled by a Chinese lender. If the country defaults, China can simply seize the cash in those accounts. These are practices that entities like the World Bank or IMF would shy away from.

Chinese loan contracts also include what’s called “no Paris Club” clauses. These essentially prevent borrower countries from including Chinese debt in collective restructuring efforts. If things go wrong, China refuses to negotiate within the traditional multilateral framework, accepting whatever terms others do. It’ll negotiate alone, bilaterally.

And then, there are confidentiality clauses. China imposes some of the most sweeping non-disclosure provisions ever seen in sovereign lending. And unlike traditional loan agreements, where the lender stays silent about a loan, here, the borrower must stay mum.

Why China lends

But why go on this massive lending spree at all?

Well, between 2003 and 2015, China’s economy was growing at nearly 10% a year. Under traditional economics, this should have increased the value of the Renminbi. But instead of letting that money affect the exchange rate, China instead held on to enormous capital surpluses — accumulating about $3 trillion in foreign exchange reserves during this period. We’ve seen this once before, when oil exporters in the 1970s recycled “petrodollars” through global banks.

Where did that money go? Most of it was invested in US Treasury securities. But lending to developing countries made for an interesting alternative: bringing both higher returns and strategic benefits.

Over those years, China had an insatiable appetite for raw materials — fuelling the second longest global commodities boom since the late 18th century. Lending to commodity producers helped secure access to those resources.

Meanwhile, these loans were structured in a way that a lot of the money would come back to China. Many of those loans were “tied”. Borrowers had to use the funds to procure goods and services from Chinese suppliers and contractors. Over time, as China’s growth began slowing and industrial overcapacity emerged, this overseas lending practically became a sales guarantee for Chinese state-owned enterprises.

In 2013, President Xi Jinping formalised this strategy with the Belt and Road Initiative. This would bring more business to Chinese contractors, while improving the infrastructure that connected China to Asia, Africa, and Europe.

The great reversal

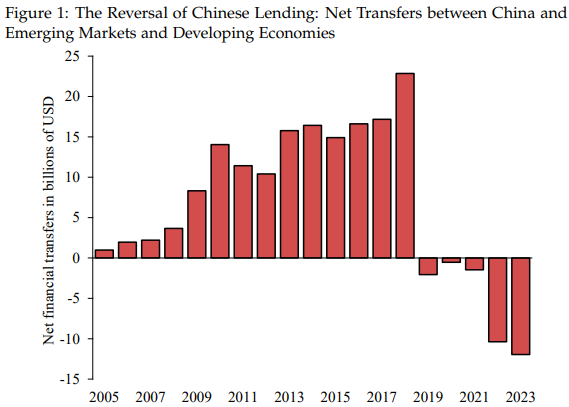

There was another reason behind China’s lending boom: it simply made sense. For years, conditions seemed perfect for lending. The world’s emerging markets needed all the financing they could get. Their growth was accelerating, and they needed massive build-outs of infrastructure to keep the wheel spinning.

Debt was affordable. After the 2008 financial crisis, global interest rates were at historic lows. Investors were looking for yield, and that took them to “frontier markets” — many of whom were issuing dollar-denominated bonds for the first time in their history. Meanwhile, commodity prices were high, giving these countries a steady stream of dollar earnings to service their dollar-denominated debt.

Their debt levels, too, were comparatively low. In fact, many countries had just received substantial debt relief through initiatives like the Highly Indebted Poor Countries program, which wrote off most external debt to traditional creditors.

Everyone had convinced themselves that the fundamentals were sound. Until they weren’t.

The good times end

Around 2014-2015, the boom ended. Non-oil commodity prices collapsed to about 30% of their peak. Suddenly, those debt burdens no longer looked manageable. Growth slowed. Credit rating agencies started downgrading countries.

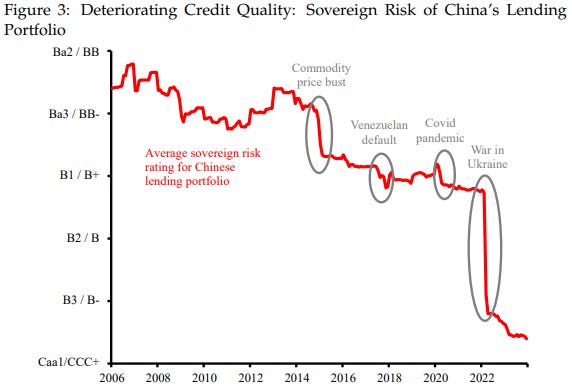

Back in 2006, the average borrower in China’s lending portfolio was rated around Ba2 or BB — not great, but not terrible. By 2024, the average rating had fallen to B-, practically junk. The years in between were punctuated by major shocks. Commodities prices collapsed. Venezuela defaulted in 2017. The COVID pandemic came around in 2020. Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022. With each shock, lending made less sense.

Meanwhile, China’s own growth had slowed. From nearly 10% before 2015, GDP growth fell to about 5.6% in the years since. With that, its foreign exchange reserves stopped growing, peaking in 2014. As growth plateaued, domestic pressures began mounting. China’s population was quickly aging, its housing market came under crisis, and some provinces were turning insolvent.

Together, these triggered a sharp reversal in Chinese lending. Since 2019, net transfers between China and developing countries have been negative. The principal and interest payments flowing back to China now exceed new lending by about $10 billion a year.

The quiet crisis

Past experience tells us that such a withdrawal of funding can be a bad thing. In the 1970s, for instance, US commercial banks lent aggressively to developing countries when times were good, and then pulled back hard when commodity prices fell and countries couldn’t pay. This sparked a debt crisis that rippled through the 1980s across much of the developing world.

Thankfully, we haven’t seen that sort of contagion yet. We have seen serious debt problems emerge — with defaults in Ghana, Zambia and Sri Lanka, and near-defaults in Egypt and Pakistan — but we haven’t seen these domino into something much bigger.

That doesn’t mean there’s no distress — only that these crises haven’t threatened major financial institutions in the West. When lower-income countries face debt distress today, there’s less urgency to resolve it compared to when wealthier, more systemically important countries are involved. But for those affected, the distress is real. Consider this: for low-income countries, interest payments on external debt hit 5.7% of exports in 2023, from just 1.9% a decade earlier. For some countries, like Egypt, Kenya, and Pakistan, debt service consumes about 13% of export earnings.

This could end badly.

China’s response

How has China dealt with rising defaults? By kicking the can down the road.

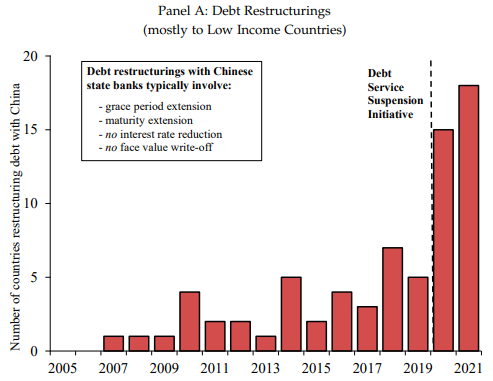

Since 2008, Chinese creditors have arranged at least 71 distressed debt restructurings — more than three times the number with private creditors, and more than all Paris Club restructurings combined. The country has become the most important player in sovereign debt renegotiations. But those restructurings rarely provide real relief. It refuses to reduce principal or interest rates. Instead, it typically extends grace periods or pushes maturities.

This provides temporary cash-flow relief. But it doesn’t address underlying problems. It pushes countries into serial restructurings — renegotiating the same debt repeatedly with the same creditor. For some countries, where China’s exposure is particularly large, it also gives “rescue lending”. dishing out short-term liquidity assistance exceeding $250 billion over the past 15 years.

But these responses treat insolvency as a liquidity problem, ignoring the fact that these countries simply don’t have the means to pay its loans back.

History shows that this rarely works. If a country’s debt burden is fundamentally unsustainable — if a country can’t conceivably earn enough to pay those loans back — rolling over payments or offering bridge loans just prolongs the pain.

In fact, it pushes those countries into a vicious cycle. Those legacy debts hang over everything. They discourage new investment and stifle growth, making the problem worse. What countries need is debt relief — write-downs that restore sustainability. But that can only happen if a creditor accepts losses. That’s a bitter pill to swallow. It took Western banks a decade to accept write-downs on their loans. For low-income countries, they took more than twice as long.

But even if China is ready, it will first have to break out of its coordination problem.

The entry of players like China have made it much harder to pull off a co-ordinated global response to financial problems. Today’s international financial system is more fragmented than at any point in recent history. Both China, as well as western bondholders and multilateral institutions, currently eye each other with suspicion. Both sides worry that if they provide debt relief, the other side will free-ride on those concessions. The result is often a paralysis that’s hard to break.

The Road Ahead

Will China’s lending resume?

Well, lenders often take their time to resume, once they’ve been burnt. Paris Club creditors never fully came back after the deep haircuts of the 1990s. Neither did US banks after their losses in the 1980s. When the US bond lending boom of the Roaring Twenties collapsed, it took more than 50 years before US lending to developing countries resumed at scale.

Should we expect China’s lending to remain subdued as well?

There’s no guarantee of that. In particular, the retreat of the United States from the global economy — with higher tariffs and reduced foreign assistance — might push China to seize this opportunity, strengthening ties with developing countries through faster, deeper debt relief.

But there’s a strong chance that China follows the historical pattern, waiting years until its banks’ balance sheets improve enough to absorb losses. That could be unambiguously bad for distressed debtor countries.

China has transformed the international financial system over two decades. But the future of its financing activity is uncertain. We don’t know if the infrastructure it funded will generate enough returns for its loans ot be repaid. We don’t know how China will work with distressed borrowers. For the countries caught in the middle — the Angolas, Zambias, and Sri Lankas of the world — the answer to these questions will determine their survival.

Tidbits

India’s Ministry of Electronics and IT just issued draft rules establishing an Online Gaming Authority to regulate online social games and e-sports. The rules require registration within 90 days, and impose penalties for non-compliance with government directives.

Source

Coca-Cola is exploring a $1 billion IPO for its Indian bottling unit, Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages, valued at $10 billion, amid growing competition from Reliance’s Campa Cola brand.

Source: Reuters

Dubai’s Emirates NBD will acquire a 60% stake in India’s RBL Bank for $3 billion, marking the largest cross-border deal in India’s financial sector and strengthening RBL’s capital.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Bhuvan

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Keep share us with kind of articles

This is one of the best articles to be published in all of Substack's portal in recent times...

Succinct/well-researched/informative...