A glass half full for Indian dairy

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Indian dairy navigates some rough pastures this quarter

Companies behind funding India’s green shift

Indian dairy navigates some rough pastures this quarter

India is the world’s largest milk producer, churning out nearly a quarter of global supply. To us, milk and dairy products are staples, with over a billion liters of milk, alone, consumed daily across the country. Some months ago, we broke down the economics of the dairy industry in our analysis of the Milky Mist IPO.

Now, some of the biggest milk companies in India are co-operatives like Amul, which are not listed. We will be looking into the top 3 listed companies in the sector: Hatsun Agro, Dodla Dairy and Heritage Foods. Their results, interestingly, diverge wildly. But underneath this variation lies the same structural trends that are shaping India’s milk industry.

Let’s get into it.

The numbers

Three major private dairy companies reported vastly different Q2 performances. In a commodity that seems as simple as milk, such divergence should ideally seem uncommon, but it has happened.

Hatsun Agro — India’s largest listed private dairy — had the most impressive quarter of the three. Its revenue jumped 17% year-on-year to ₹2,428 crore. But the highlight was its profit-after-tax (PAT), which soared by a whopping 73% y-o-y to ₹110 crore.

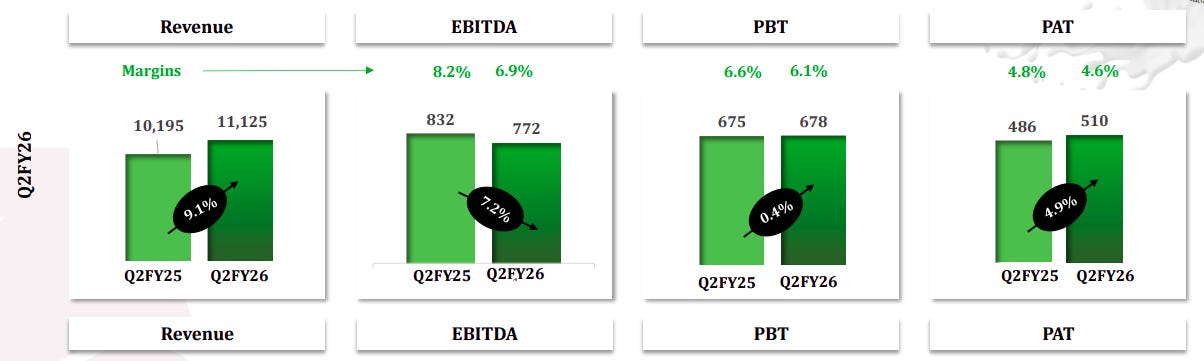

The results of Heritage Foods, however, stood in stark contrast compared to Hatsun. Its revenue grew 9% to ₹1,113 crore. But profitability has taken a hit — the EBITDA has fallen by 1.2% from last quarter and 7% from last year. Heritage’s day-to-day operations, it seems, are finding it hard to make money.

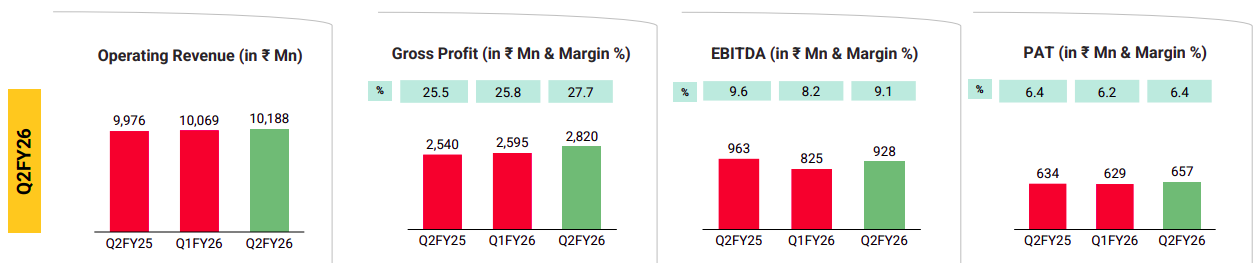

Dodla Dairy sits somewhat in between these two. Its revenue grew at a modest 2.1% y-o-y, to ₹1,019 crore. Last year’s revenue figures, however, included ₹165 crore in bulk commodity sales that Dodla intentionally curtailed. Excluding those low-margin bulk trades, the company’s underlying revenue growth was actually 13%. PAT was up 4% to ~₹66 crore.

Milk prices boil over

The first reason for such divergent financial outcomes is milk inflation.

Heritage, and even Dodla to some degree, saw their margins squeezed by a sharp spike in the price of raw milk. Heritage pretty much admitted this in their con-call.

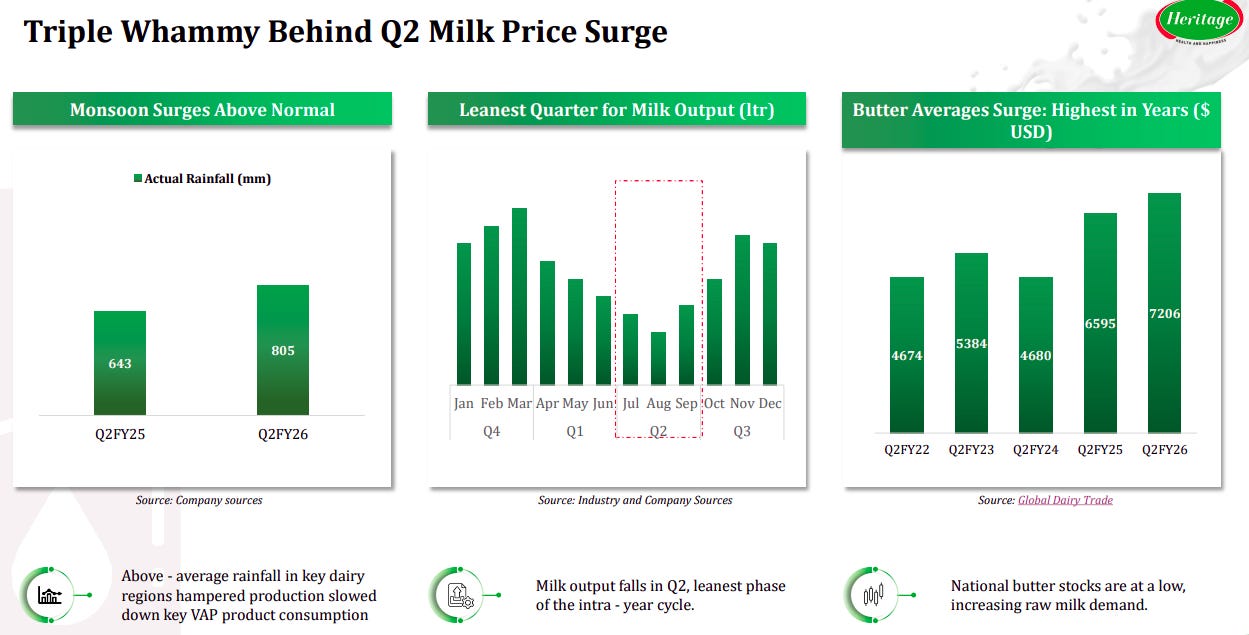

Now, the second quarter of any year is usually a lean season for milk production. Cows produce less milk in the summer and monsoon months. Meanwhile farmers take the benefit of the rains to grow more fodder to feed their cattle, ahead of the flush season which starts from the third quarter. So, in Q2, demand naturally outpaces supply, leading to higher milk prices.

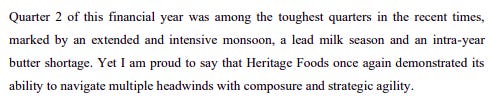

However, Q2 of this year has been unusually bad. And all the fingers point to one suspect: the weather. Here’s Heritage talking about it:

The Southwest monsoon which brings rains to much of India in Q2 has been excessively heavy and unpredictably long, causing floods. We’ve covered, before, how this unpredictability has hurt demand for coolers and ACs. It turns out, milk has not escaped the weather’s wrath either. Floods and waterlogged fields disrupted fodder availability and made milk collection from villages difficult.

But if that’s the reason, shouldn’t the entire industry have been hit equally? Why did Heritage alone bear its brunt?

The answer lies in geography — where these companies procure milk from. Most of Heritage’s procurement is concentrated in just two states: Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Those were the two states hit worst by the rains this quarter. As a result, Heritage procured 2% less milk compared to last year — and at prices that were 6% higher than last year. Meanwhile, Heritage has not been able to fully pass on higher prices to consumers, hurting margins.

Dodla and Hatsun, in contrast, are much better diversified regionally. While both of them do have exposure to AP and Telangana, they are not as heavily dependent on those 2 states as Heritage. Recently, Hatsun also acquired Odisha-based Milky Moo, giving them a readymade base there. This wider base allowed both Dodla and Hatsun to increase milk procurement compared to last year.

Just to add salt to the Heritage’s wounds, a shortage of butter and ghee made things worse. Recently, global butter prices surged to multi-year highs, prompting Indian producers to ramp up exports. Meanwhile, despite high prices, domestic ghee consumption stayed robust. Low butter stocks forced dairies to procure more milk to extract cream, worsening the milk shortage. In a strange twist of irony: our love for ghee created a scarcity of milk itself.

So, Heritage has been bitten by the four horsemen of the (milk) apocalypse: a cyclically-leaner Q2, bad weather, regional mix, and increased demand for butter.

More than milk

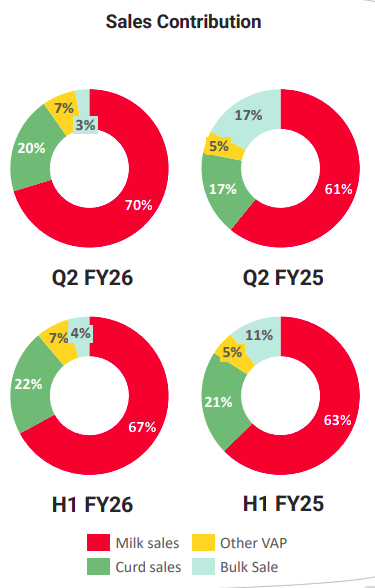

A huge talking point for milk producers this quarter was the growing importance of Value-Added Products (VAP) like curd, ice cream, paneer, cheese, flavored milk, and so on — all of which carry higher margins than regular milk.

But each of our three players is playing the VAP game differently.

Hatsun, of course, is playing this game the best. Close to half of its revenue comes from VAP — much, much higher than its competitors. It is a market leader in several VAP categories: most notably, ice-cream.

You’ve probably seen “Arun Ice Cream” in your average grocery store, at least if you’re from South India. Arun is Hatsun’s crown jewel, and is one of the biggest ice-cream brands in all of India. In fact, Hatsun began as an ice-cream business before moving into milk. The Arun brand is one of the biggest reasons why, even when milk procurement costs have risen, Hatsun has yielded superior numbers. And ice-cream has, well, sweeter margins than other VAP like curd, butter and ghee.

Yet, ice-cream is far from the only VAP Hatsun has established market leadership in. As per their con-call, It seems like their curd and butter brands are doing very well, too. This focus on VAP is why their profits grew by 70% from last year. And now, they’re doubling down — with plans of launching a range of high-protein dairy products.

Heritage and Dodla are behind Hatsun in this race, but they aren’t sitting still, either.

Heritage’s VAP contributed 38% of all sales in Q2, of which curd made up 70%. VAP revenues grew 18%, far faster than regular milk. And they’re doubling down on these lines as well. Heritage has been spending ₹150 crore in capex annually to build capacity just products like ice-cream, yogurt and paneer, hoping to structurally make the business more profitable in time.

Dodla has historically been a milk-centric business. This quarter, however, VAP made up ~30% of revenue, and even within VAP, curd made up over 70% of sales. This over-reliance on a single product could become a risk, but Dodla is actively investing to expand its VAP range.

Compared to Hatsun, however, both Dodla and Heritage are playing catch-up, despite heavy investments in VAP. Even within VAP, they’re heavily reliant on lower-margin products like curd — which spoils easily. Hatsun’s top-notch ice-cream business puts it on a different plane.

If anything, Hatsun’s lead is growing larger. Its early investments — in capacity, cold chain infrastructure, and so on — are bearing fruit right now.

For instance, a few years ago, Hatsun commissioned a mega dairy plant at Govindapur (Telangana). While initially it might have run at low utilization, now Hatsun is enjoying higher utilization on this plant as demand catches up. Hatsun also invested early in establishing a fully refrigerated supply chain — the first dairy company in India transporting milk and VAP 100% under refrigerated conditions. All of this adds to its margins.

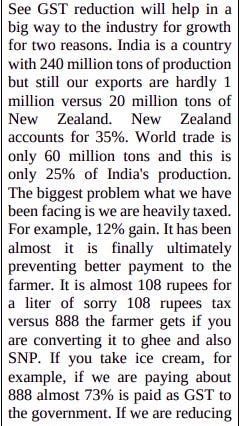

What has also given Hatsun’s ship more wind in its sails is the new GST regime. Products like ghee, butter, and cheese were earlier taxed at 12%. Under the new GST rules, however, the rate has now been cut to 5%. Paneer, similarly, went from 5% to 0%. Pure milk remained unchanged at 0%, however. Compared to Heritage and Dodla, Hatsun’s portfolio is much more heavily titled towards VAP that enjoyed a tax break due to the latest reforms. Which is why it’s really hopeful of a further boost in its VAP sales.

Loyalty

Something that we found while researching these brands is that seemingly, brand loyalty matters a lot in dairy. The idea is that once consumers take a liking to a particular brand of milk or VAP, they’re unlikely to switch to another. So, a strong brand recall might really help. Here’s Hatsun exhibiting their extremely-strong belief in brand a blunt, hilarious way:

But Hatsun might have a point here. Having started in 1970, Hatsun has built some iconic, thousand-crore brands over decades, allowing it to develop a loyalty that it can charge a premium for. And it seems like this brand premium does show up in the numbers. Hatsun’s EBITDA margins this quarter are 13.4% — way above Dodla’s 9.1% and Heritage’s 6.9%.

Heritage and Dodla, which started much later than Hatsun, don’t enjoy the same kind of brand trust. But they, too, know just how important it is. Heritage has ramped up marketing spend significantly, which has helped raise awareness rates and trial rates for their products…

…while Dodla has been expanding its brand initiatives across television, OTT, and even physical festival sites.

Conclusion

In these results, we’ve gotten a sense of what milk companies hold most dear to them.

Milk procurement became costlier this quarter, and not because companies have fallen asleep at the wheel. The weather (and maybe climate change more broadly) has played spoilsport, especially for businesses that were too reliant on regions heavily exposed to excessive rains. Value-added products and brand differentiation also play a huge role in the chase of higher margins.

But what also matters is scale and timing, which has significantly benefited Hatsun. Heritage and Dodla are only making their big moves now, and we can’t say for sure if their big bets will eventually upset the industry. Even without other headwinds, that road is steep with no clarity on the destination.

Companies behind funding India’s green shift

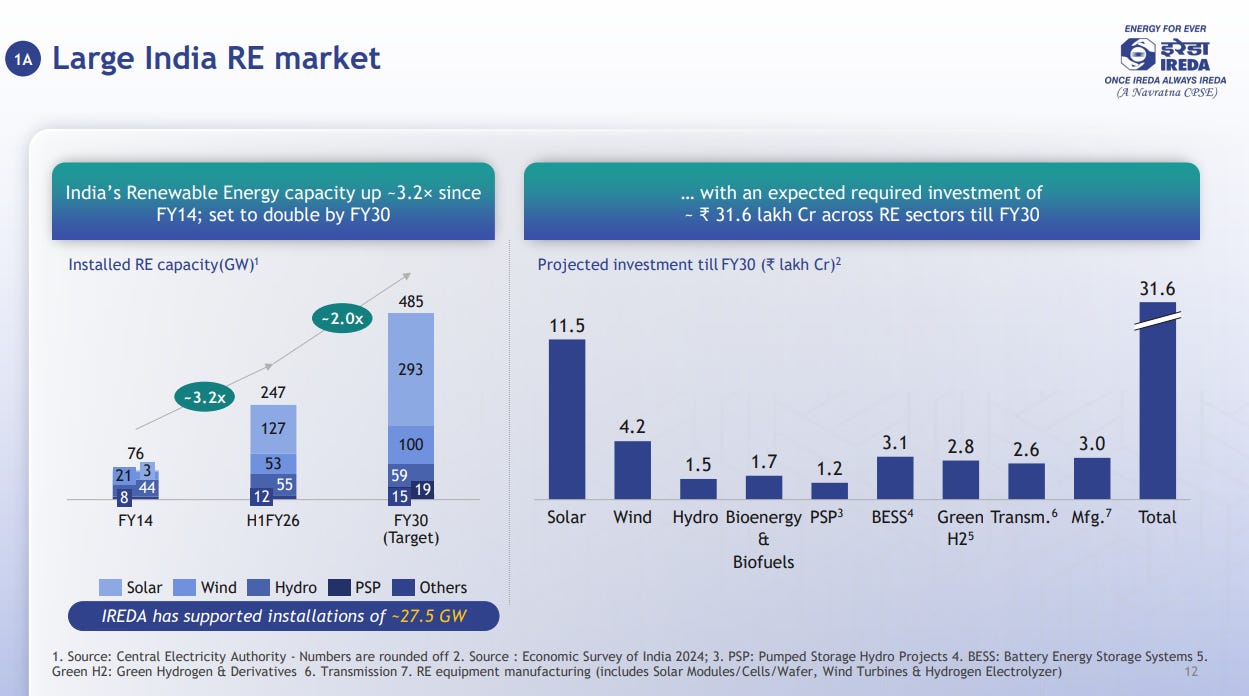

India is in the middle of a massive energy transition. We’re building renewable energy, upgrading the existing network, revamping our electricity distribution, and more. According to the National Electricity Plan, India’s power capacity may reach 609 GW by 2027 and 900 GW by 2032.

But this won’t come cheap. To get there, we’ll require an estimated ₹32 lakh crore in capital spending from FY26–32. Typically, three of every four Rupees spent on such projects is funded by debt. Our grand project of energy transition, then, will need lakhs of crores in loans.

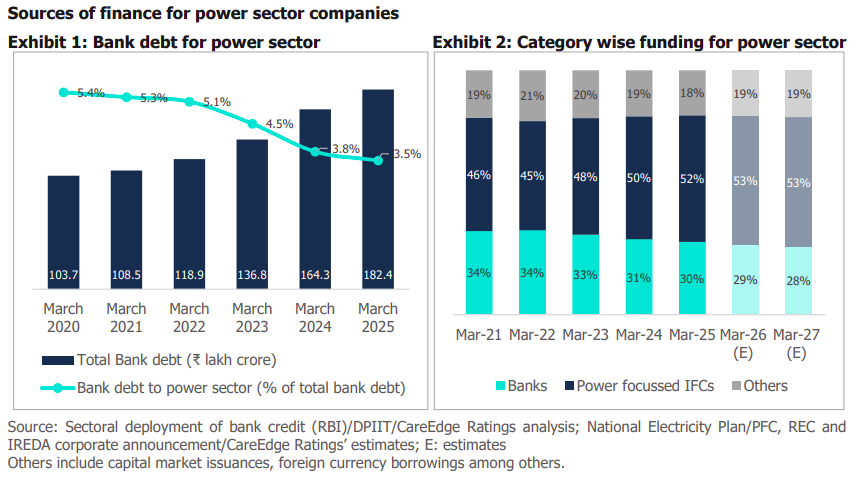

Yet, traditional banks are hesitant to jump in, and for good reason. Not too long ago, power companies dragged Indian banking into a massive NPA hole — loans of ₹1.74 lakh crore going sour — which took them the better part of a decade to escape.

So where does the money come from, then? Well, most of that burden has now fallen on a special class of institutions.

Enter Power Infrastructure Finance Companies (P-IFCs)

There are companies — often government-backed — that dedicate themselves purely for this funding power projects, called Power Infrastructure Finance Companies, or P-IFCs. The big three are Power Finance Corporation (PFC), REC Limited (REC), and Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA).

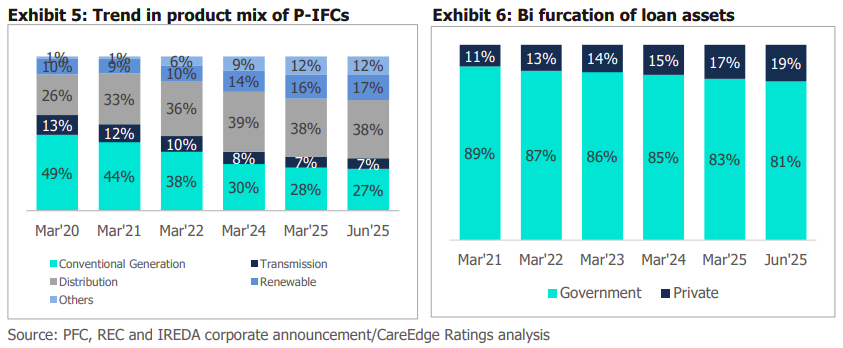

These have become the primary lenders for power projects, funding the majority of India’s power sector debt — as much as 52% of outstanding power sector loans, as of March 2025. And their share in the sector’s financing is still rising, even as banks’ share has declined.

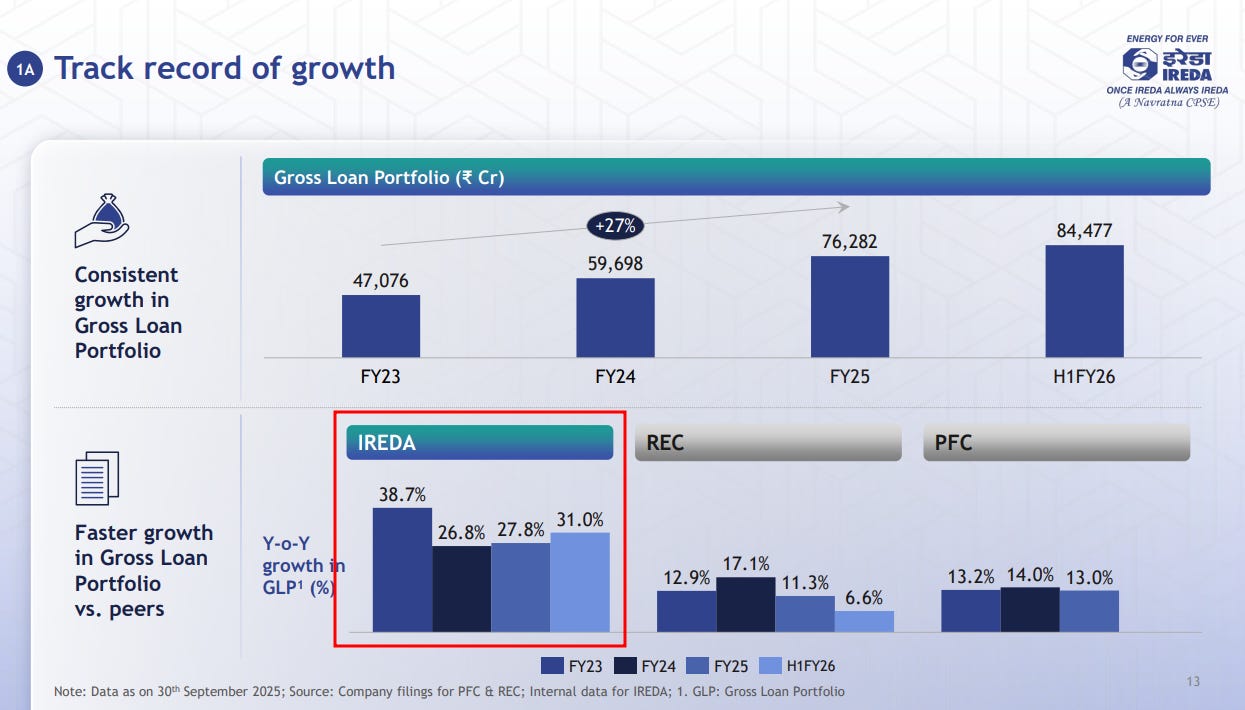

Between 2020 to 2025, P-IFCs expanded their loan books at a CAGR of around 11.5%. This might not sound like much, but consider it in its context — through much of the 2010s, the sector saw a period of stagnation, and even degrowth, from that base this is an impressive comeback.

This period has also seen major shifts in who they lend to.

Much of this lending used to be to traditional thermal power generation projects. But that is changing fast. Loans for renewables projects, for instance, rose from about 10% of the total portfolio in 2020 to roughly 17% by 2025. At the same time, lending to coal power plants fell sharply—from nearly half of all loans in 2020 to just 27% in 2025.

Traditionally, P-IFCs lent mostly to government-owned utilities (state electricity boards, state generation companies, etc.), and these still make up over 80% of their loan books. But there’s a gradual shift here as well. Private players — mainly renewable power producers — now account for 15–20% of loans, from about 10% five years ago.

That’s partly because the economics of renewables have improved dramatically. Plus, the government’s push for energy transition and easier access to green finance have made private developers more active and creditworthy, encouraging NBFCs and banks to lend more confidently to them.

The Policy-Driven Lending Angle

What explains the growth in the sector’s lending?

This isn’t merely a product of more organic, market-driven demand – a lot of the surge has been policy-driven. In recent years, the government has launched special programs to revive or reform the power sector. Companies like PFC or REC often serve as the nodal financing agencies for these schemes. That is, these companies are made accountable for those schemes, and become a single point of contact for companies that want to avail of it.

For instance, during COVID the government rolled out a Liquidity Infusion Scheme (LIS) to bail out DISCOMs, paired with a Late Payment Surcharge (LPS) scheme to clear the huge backlog of unpaid power bills DISCOMs owed generators. The money for these rescue packages was disbursed by PFC and REC. In their books, this looked like a spike in their loan disbursements — but these were, in fact, one-off programs driven by the government.

Much of the jump in P-IFCs’ loan book in recent years comes from such schemes.

As those schemes wind down, there’s a new policy push: the Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS). This is a government initiative to reform electricity distribution – things like installing millions of smart meters or upgrading wires and substations. Once again, PFC and REC have been made the nodal agencies for RDSS, and that shows up in their numbers. PFC, for instance, had approved over ₹1.17 lakh crore of loans for various RDSS projects by late 2023 alone.

With this in mind, let’s turn to how the big three P-IFC companies are doing, through their latest quarterly results.

Power Finance Corporation (PFC)

Power Finance Corporation is the largest of the trio, and a parent of REC. Its loan book spans generation, transmission and distribution, and lately, it has even added non-power infrastructure to the mix. If there’s a big Indian power project, chances are PFC is involved.

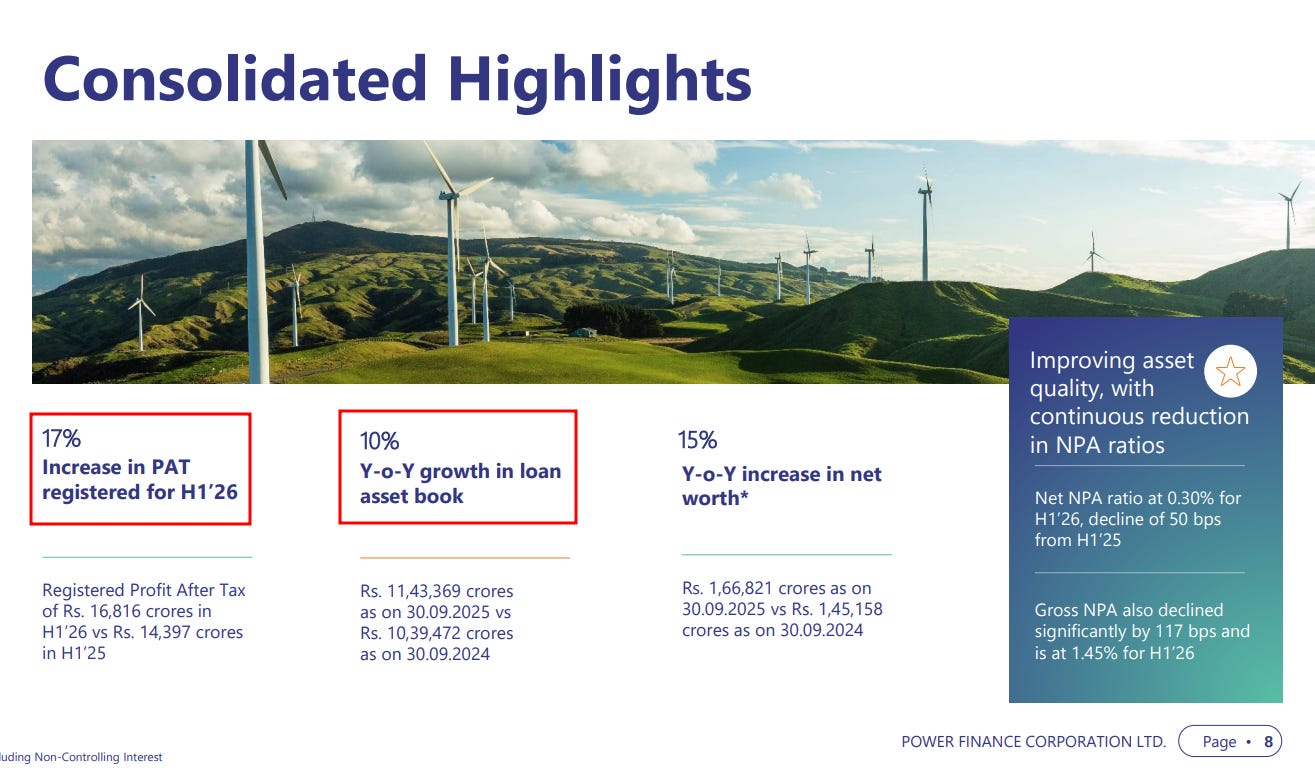

PFC just delivered solid results. In the first half of FY26, its consolidated profit after tax was a best-ever ₹16,816 crore, up 17% from last year. Its loan book expanded to ~₹11.43 lakh crore — roughly 10% up year-on-year — by the close of Sept 2025. Behind this growth was the funding it gave to renewable energy projects, as well as its large disbursements to distribution companies under schemes like RDSS.

PFC’s asset quality looks remarkably good for a lender in the infrastructure space. Its gross NPAs fell to just 1.45% by the first half of FY26. This was an improvement of 117 basis points in just a year, as the company resolved some long-stressed power projects and recovered past dues. Its net NPAs, meanwhile, are almost negligible at 0.3%.

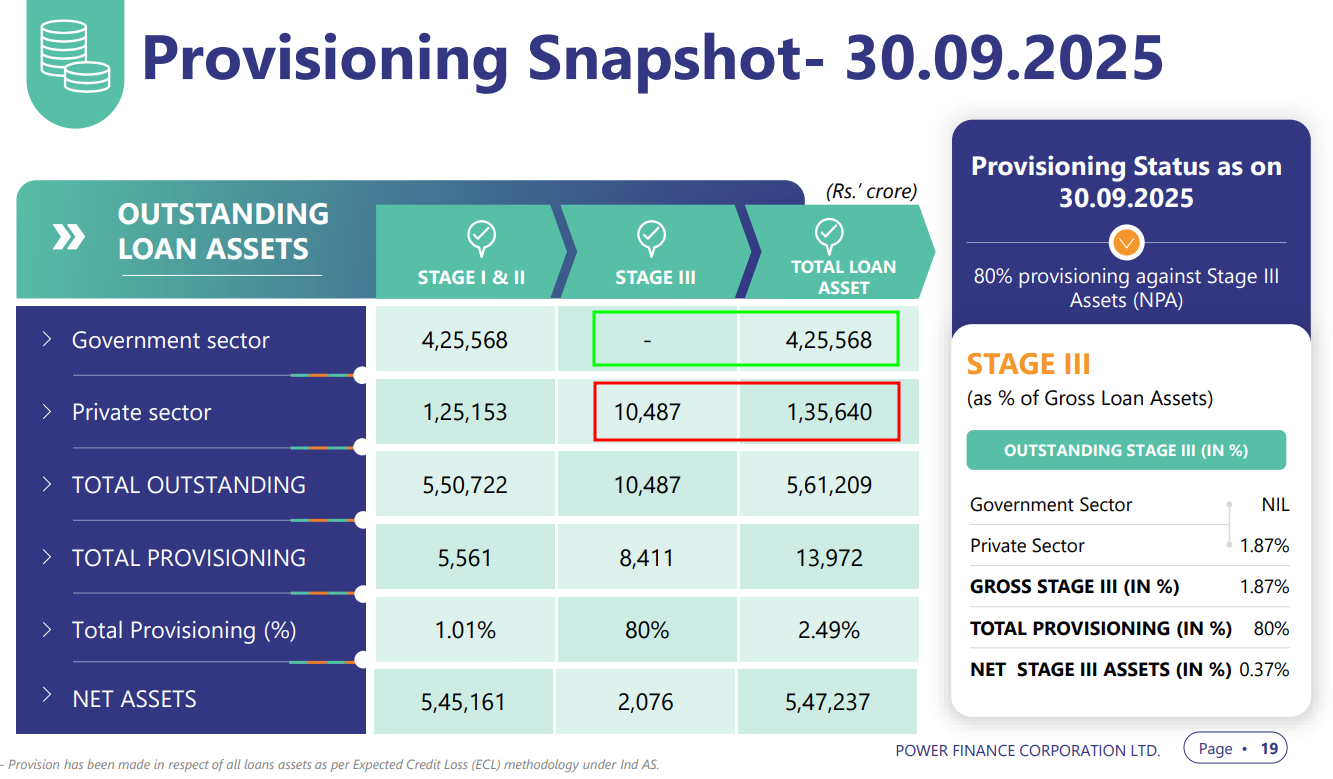

How did it manage such clean books? PFC benefits from its heavy exposure to state entities. When these are in trouble, their loans are often restructured or backed by a state guarantee. These are never classified as bad loans, no matter how long their payments are pending. Purely commercial lenders, meanwhile, would have to label a defaulting borrower as NPA.

So, the main takeaway from PFC’s pristine 1.45% NPA is that loans to state utilities are inherently protected. The risk the company takes is much more visible in its private sector lending, where NPAs stand at over ~7.7%.

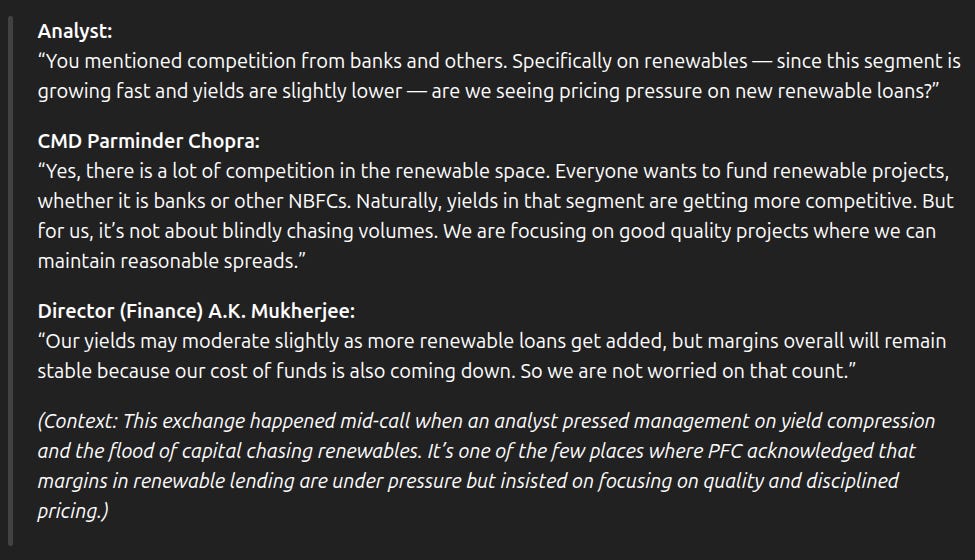

PFC is gradually shifting its own lending in line with India’s energy trends. It still finances big thermal plants, but there are hardly any ones coming up. Renewables are where its growth is coming from, as PFC’s management noted. The yield on these loans, however, is slightly low, with intense competition to lend to the segment.

REC Limited (REC)

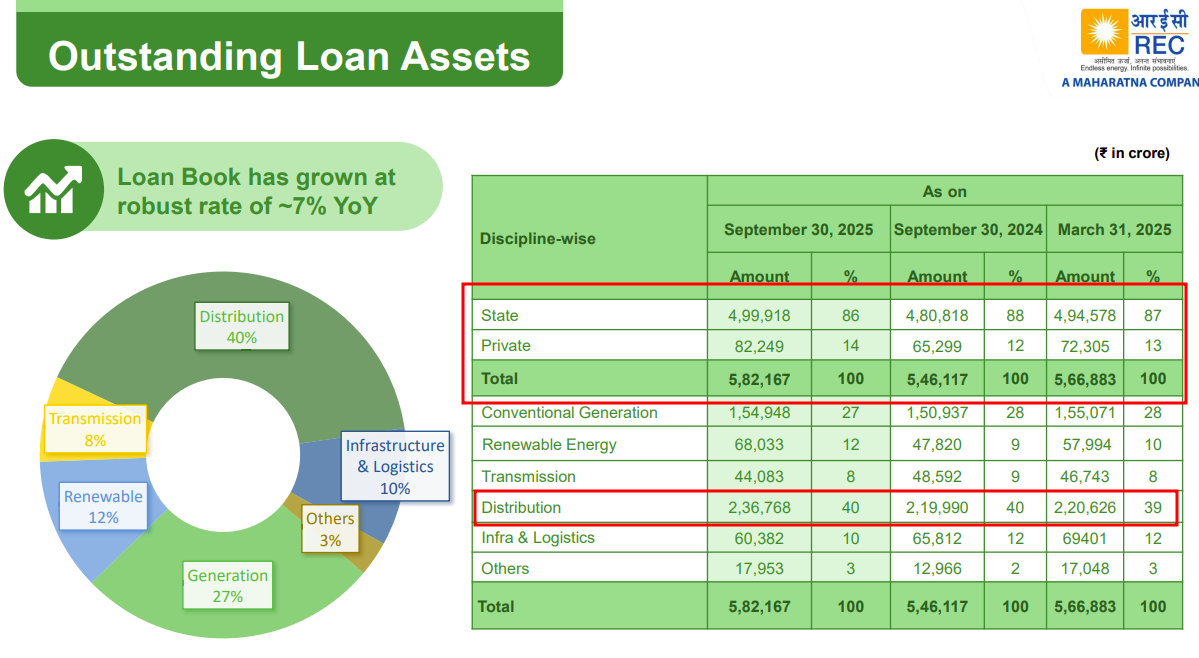

REC historically focused on financing distribution networks and rural electrification, and that’s where 88% of its lending still goes. It has always been the go-to financier for the government’s distribution schemes — it was the nodal agency for the government’s 100% household electrification drive, and is currently a nodal agency for RDSS. This does, however, mean that REC’s fortunes often rise and fall with government policy pushes.

Most of its loan book, like PFC, is dominated by government companies — which make up roughly 86% of its lending. Large chunks of that is lent to distribution companies and state electricity boards.

Over time, however, REC has been entering newer segments. As a Maharatna PSU, its footprint is now visible across different segments. In fact, REC has outpaced PFC in diversification. About 12% of its portfolio is now in non-power infrastructure — like metros, ports, and other government projects. Just 3% of PFC’s lending, meanwhile, goes there.

Like PFC, REC too had a great half-year. The company’s own borrowing costs were low, and it took low credit losses. This gave the company its highest ever half-yearly profit, with a PAT of ₹8,877 crore — 19% above last year.

Meanwhile, its loan book grew to ₹5.82 lakh crore — 7% higher than last year. That looks relatively moderate, but consider that REC had already seen a bump from scheme lending in recent years.

Much like PFC, REC too benefits from the fact its loans to state entities rarely turn into write-offs. This makes its asset quality front seem exceptionally clean — with net impaired assets at just 0.24% of loans, and gross NPAs around 1%.

Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA)

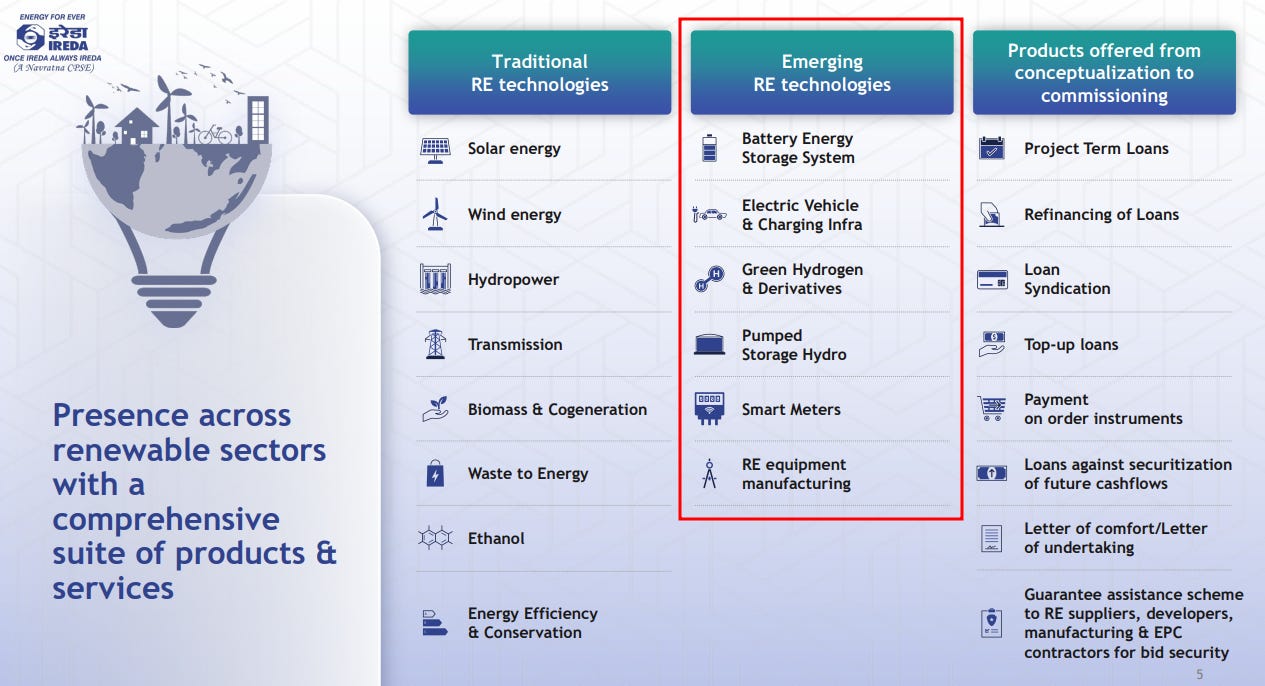

The Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) is the smallest of the trio. But while niche, its role is crucial. It is run under the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, and focuses exclusively on renewable energy and energy efficiency projects. It has been instrumental in funding solar, wind and hydro projects, and with time, is also focusing on emerging areas like green hydrogen and energy storage.

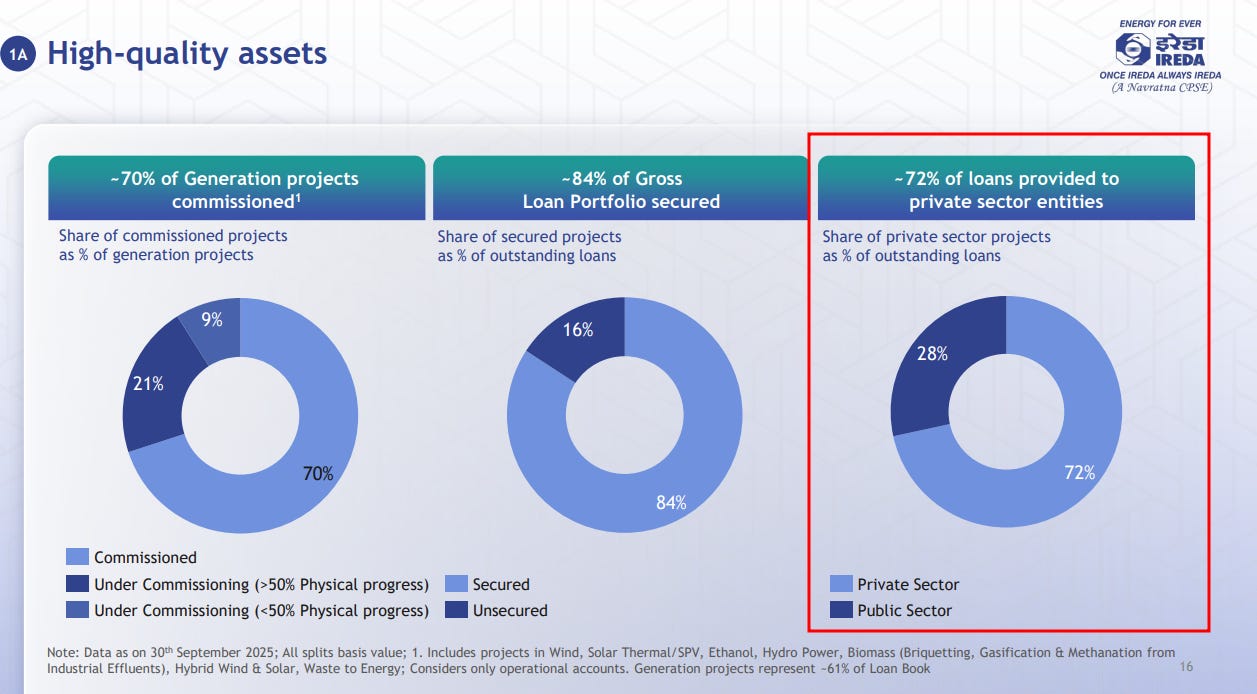

Unlike PFC/REC, which lend heavily to state-run entities, a large number of IREDA’s borrowers are from the private sector, although it does fund some public sector renewables, like solar parks. This makes IREDA’s business somewhat different — it’s more specialized, and historically has a somewhat higher credit risk.

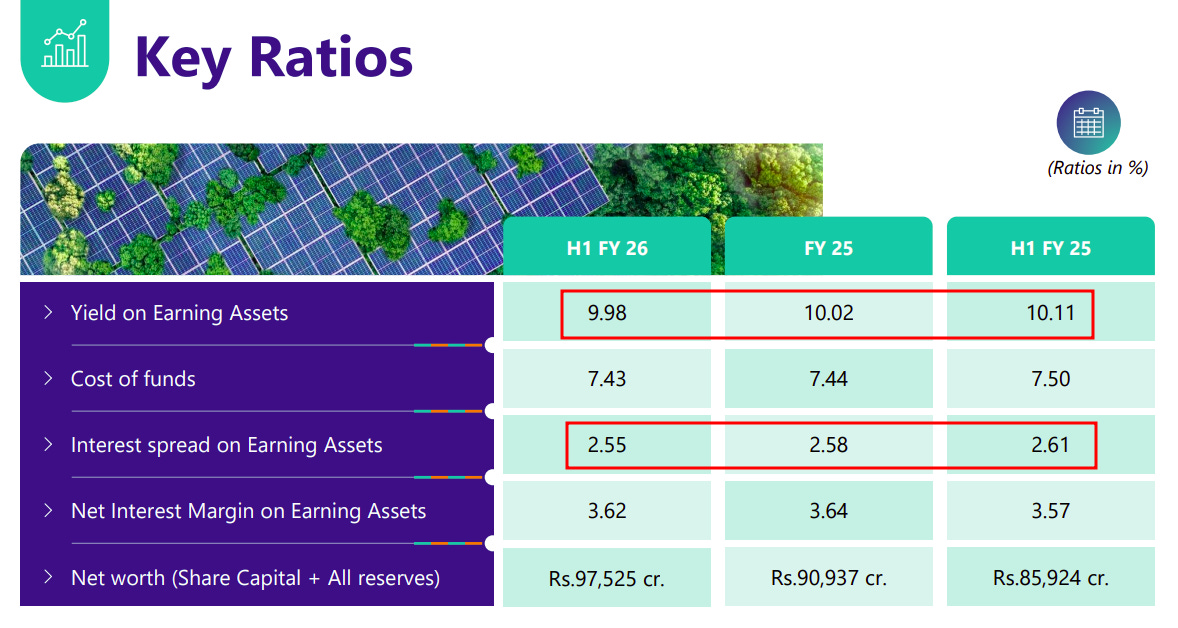

As India transitions its electricity mix, IREDA is growing rapidly. Its loan book stood at ₹84,477 crore at the close of September 2025 — a whopping 31% higher than a year ago. With this larger book, along with stable interest spreads, its operating profit jumped ~52% year-on-year. This makes it the fastest growing of the three power IFCs in discussion.

However, its bottom-line growth was much more muted — at ₹796 crore, its Q2 profit after tax was just ~3% higher than last year. This could be a result of higher provisions or borrowing costs. Notably, one of IREDA’s borrowers slipped into NPA in mid-2025, due to a court order involving tariff issues in Andhra Pradesh. This may have forced IREDA to book a provision.

This hints at a larger facet of IREDA’s business: while business is growing fast, its loan book also shows pockets of stress. Its gross NPA ratio is about 3.2% — far higher than PFC/REC’s ~1% levels. That’s simply the reality of lending to numerous private projects in the somewhat untested space of renewable energy.

A bumpy road

As government-led vehicles that are pouring funds into areas that desperately need development, each of these three companies have indispensable in financing India’s energy transition. But there are nuances to consider.

Overreliance on policy-driven lending

A significant part of PFC and REC’s recent growth spurt has come from government schemes — many of which are one-off or short-term pushes. Once a scheme runs its course, disbursements under that program stop. For example, the LPS scheme for clearing DISCOM dues gave a big boost to loan books in FY24-25, but those were lump-sum emergency loans. Similarly, RDSS is fueling a lot of lending now, but it has a fixed outlay and timeline.

This makes their numbers lumpy. Unless there’s a continuous pipeline of new schemes, P-IFCs could face a growth slowdown. This opens a question of sustainability: can these companies keep up double-digit loan growth once the current programs peak?

Low NPAs are not the whole story

As we’ve noted before, the impressive NPA numbers at PFC and REC come from their exposure to government-owned entities, which essentially carry an implicit sovereign guarantee. And so, stress doesn’t always translate into an NPA in their books.

But crucially, that doesn’t mean that stress is absent. It’s just not reported.

For instance, many state DISCOMs are in poor financial shape, but their loans from PFC/REC are still considered “standard”. That doesn’t mean these companies will receive payments in time. The quality of their assets needs monitoring beyond the headline numbers.

By contrast, IREDA’s higher NPA ratio (~3%) offers a peek into the actual stress levels in parts of the power sector.

Profit margins may have peaked?

PFC and REC have enjoyed very healthy net interest margins in recent years — ~3.5-3.6%. They’ve benefited from low funding costs at one end, and decent yields at the other. However, going forward, those margins could face pressure. As more lenders chase renewable energy projects, the competition is heating up — as we saw with PFC’s yield on assets.

Another factor is the interest rate cycle: if interest rates stabilize or fall, P-IFCs will see their asset yields adjust down, while their own borrowing costs might come down with a lag, if they’ve locked-in higher-rate funding earlier. Their margins, therefore, might compress a bit.

Wrapping Up

At their core, PFC, REC, and IREDA are lenders — but calling them just that misses the point. Their growth, profitability, and even risk appetite are constantly shaped by external forces: government policy, energy transition priorities, and the fiscal health of state utilities. Often, their lending isn’t driven by market demands, but by where the government needs capital to flow. That means these aren’t traditional lending stories, where margins and NPAs tell the full tale. They’re a way to take an exposure to India’s power transition, anchored in policy.

If you’re assessing these companies, look at the sectoral direction, state finances, and reform momentum. Those, rather than traditional financial metrics, are where the real story lies.

Tidbits

Novo Nordisk has slashed prices of its obesity drug Wegovy in India by up to 33%. Wegovy’s lowest dose of 0.25 mg is now priced at ~₹10,850, down from over ₹16,000 earlier.

Source: ReutersJSW Steel is reportedly planning to offload 50% of its stake in Bhushan Power & Steel Ltd. (BPSL), worth ~₹16,000 crore. This was right after the Supreme Court upheld JSW’s acquisition of BPSL after a long battle in court.

Source: The Hindu Business LineIndia’s refiners will receive their full-term crude oil allocations from Saudi Arabia and Iraq for December 2025, while also allowing more optional contracts. Some Middle Eastern producers, like Saudi Aramco and SOMO, have even reduced prices amid uncertain global demand.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish.

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Very well explained and to the point. I truly appreciate all the hard work you put in to make things simpler for us.

A good article!

would also like to read about state-level milk players like Nandini, Aavin etc.. if that's possible,

KUTGW