A 2005 deal could cost India big today

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Satellite Dreams and Courtroom Wars: The Devas-Antrix Saga

Understanding India’s shrimp industry

Satellite Dreams and Courtroom Wars: The Devas-Antrix Saga

There’s an apartment in the posh 16th arrondissement of Paris — a locality full of museums and foreign embassies. The €3.8 million apartment belonged to the Indian government, and was once the home of the Deputy Chief of India’s mission. But one day, in 2022, in a scene straight out of a diplomatic thriller, a French court handed investors in a Bengaluru-based start-up the right to seize the apartment. This was one of the first shots in a cascade of similar attempts over Indian property located all over the world.

Behind this case was a decade-old satellite deal that had gone spectacularly wrong.

In the latest chapter of this sorry tale, last week, the Indian government got another piece of horrible news. All nine justices of the US Supreme Court unanimously struck down a key legal defense that Antrix, an arm of ISRO, was relying on to avoid enforcement of arbitration awards in American courts. The immediate consequence? A $1.29 billion award against India can now move ahead in foreign courts.

Foreign investors that were stung by our policy decisions, and frustrated by India’s perennial legal logjam, can suddenly access the assets we own in the United States — from PSU bank accounts to diplomats’ homes. This isn’t just a story of a few properties. It signals something much bigger — a PSU company can’t just break contracts as it wishes, or Indian assets all over the world could be dragged into the fight.

The Deal

But let’s tell you the story from the very beginning, as it unfolded.

Back in 2005, India’s space program was riding high. ISRO had proven it could launch satellites at prices that few entities in the world could match, and its commercial arm, Antrix, was hungry for revenue.

That’s when it came across Devas Multimedia — a Bengaluru startup founded by ex-ISRO scientists who’d attracted Silicon Valley venture capital. It planned to stream multimedia content and broadband straight to 3G handsets, leap-frogging India’s patchy ground networks. This included plans for satellite-based internet in rural areas — an idea that Elon Musk’s Starlink is now pursuing globally.

The two came up with a deal. Antrix planned to launch two satellites into geostationary orbit. It would lease 70 MHz of precious S-band spectrum on those satellites to Devas, for 12 years. In return, Devas would pay ₹167 crore upfront, and help pioneer satellite-based digital services across India. It was a bold plan — Netflix-meets-satellite TV, delivered directly to mobile phones — which was revolutionary for 2005. It drew interest from all over the world. It was backed by Deutsche Telekom, Mauritius-based funds, and US investors who were keen to tap into India’s digital future.

This was smart business for Antrix too. Instead of launching satellites that sat half-empty, they had found a way to generate steady commercial revenue. The project wasn’t without its snags: the S-band spectrum they were getting was the same frequency used by military and strategic communications. But it seemed like both sides were interested. It was a pioneering project, after all — and such complications were bound to exist.

Both sides spent years preparing. They built satellites, obtained licenses, and secured international approvals. Everything was on track for launch. And then everything changed overnight.

Cancellation, confusion, and chaos

In February 2011, the Cabinet Committee on Security, India’s highest decision-making body on strategic matters, decided it needed that S-band spectrum for “strategic and security purposes.” Antrix was instructed to terminate the deal immediately.

The timing was not coincidental. Late in 2009, the ‘Radia tapes’ were leaked. These featured more than 5,000 conversations between some of India’s top businesspeople and politicians — all around securing a part of the 2G spectrum for themselves.

The public was mad at the government’s “spectrum give-aways”. Anything to do with the word ‘spectrum’ came under the scanner. And a deal that handed valuable and sensitive satellite spectrum to a private company suddenly looked politically toxic.

And so, Antrix informed Devas that because of a policy change by the Government of India, it could no longer give away spectrum in the S-Band for commercial purposes. To Antrix, this was what lawyers call a “force majeure” — a fancy legal way of saying the contract had become unworkable due to something outside Antrix’s control. Along with this letter, they sent a cheque for ₹58 crore, to reimburse Devas for the upfront fees they had paid to reserve its satellite spots.

But Devas was not satisfied. Force majeure clauses typically cover unforeseeable events, like natural disasters or wars. Antrix was an arm of the government itself. How could a government claim that its own policy decisions were unforseeable? To Devas, this looked like a “self-induced” event — essentially, the Indian state was claiming it couldn’t fulfill a contract because it had changed its mind.

To Devas, the government was going back on its word, and for that, it owed Devas some serious money. To the government, it was taking a decision on national security, and a mere commercial contract had no place in such a decision.

The stage was set for a legal battle that would span continents.

Arbitration and a Global Asset Hunt

If Devas was purely an Indian company, it may have soon run out of options. But it was a company backed by major international investors. And that gave it a whole raft of new legal options. According to the original Antrix-Devas contract, any disputes between the two parties would be sent to international arbitration — outside India’s legal system. This was the option Devas chose to pursue.

By September 2015, a three-member ICC tribunal in Delhi delivered a unanimous verdict: Antrix had "wrongfully terminated" the contract, and it would have to pay. The numbers were staggering: $562.5 million in damages — and another 18% annual interest. Devas had originally sought $1.6 billion, but even this "reduced" award was massive by Indian standards.

But Devas’s investors weren’t done. Its foreign shareholders — entities based in Mauritius and Germany — filed separate claims under India’s Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) with those countries. These treaties are meant to protect foreign investors from arbitrary government actions. Between 2016 and 2020, these BIT tribunals also ruled in favor of the investors — adding another €195 million to India’s bill.

The Indian government, however, has refused to pay anything out. And so, those awards have been racking up interest.

Here’s the math: $562.5 million at 18% annual interest since 2015 has now ballooned up to roughly $1.3 billion. Add the BIT awards, and India faces a potential liability exceeding $1.5 billion. Think about that number for a moment. It’s roughly equivalent to India’s annual space programme budget. For a deal that would originally bring ₹167 crore to India’s coffers, it is now liable for a penalty 60 times that amount.

But what was Devas to do if India wouldn’t pay?

Its investors launched a worldwide hunt to claim Indian government assets. Anything that any arm of the Indian government owned was fair game. Armed with their arbitral awards, they began seeking rights over these properties all over the world. That is how, in January 2022, a Paris court allowed investors to place a “judicial mortgage” on the €3.8 million Indian government apartment.

Following the victory, a Devas adviser warned: “India has assets like this all over the world. This is just the beginning.”

It didn’t have the same success everywhere. The UK proved trickier. It had a law — the State Immunity Act 1978 — that protected the assets of other sovereign countries from such proceedings. Canada saw partial success: the Quebec Superior Court granted Devas investors’ request to attach 50% of Air India funds held by the ‘International Air Transport Association’ or IATA.

But the real theatre unfolded in the United States. In 2018, a federal court in Seattle confirmed the ICC award and entered a $1.29 billion judgment against Antrix. And this meant that all Indian assets in the United States were up for grabs. Investors began hunting for attachable assets of whatever variety — PSU bank accounts, revenue streams, and overseas holdings of public companies like Air India (before its privatization).

But then the Ninth Circuit threw a wrench into the works. In 2023, it held that US courts lacked jurisdiction over Antrix, because it didn’t have a sufficient connection to America. Under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA), foreign states are generally immune to court proceedings. A US court can exercise jurisdiction over them (or their off-shoots) only if there’s an exception to this immunity. One such exception is the “arbitration exception” — foreign countries can be dragged to court if the case is about enforcing an arbitration award made under a treaty.

Did this apply here? The Ninth Circuit held that it could, but before that, the court would have to see if there were “minimum contacts” between the foreign entity and the US. This rule usually looked at whether a US court could go after private companies. But the Ninth Circuit took the same logic to a government company like Antrix. This could have derailed investors’ attempts to take over Indian property in the United States — at least until the Supreme Court stepped up.

But before we get to that, let’s take a detour.

The fraud counter-offensive

There’s a twist in the case.

In 2015, the CBI registered an FIR against Devas and its officials — claiming that they bagged their original deal through corruption. A year-and-a-half later, the CBI completed its investigation, and filed chargesheets indicting everyone for “criminal conspiracy, criminal misconduct, cheating and other corrupt practices”.

Essentially, the CBI said that it had completed its investigation, and found that there was corruption at the heart of the deal. But Devas’ key officials all live abroad, and unless they come to India, they can’t be put on trial. And so, the CBI’s investigation hasn’t yet been confirmed judicially. We don’t know if the CBI actually found enough evidence to back its case.

But this became something that the Indian government could fall back on before Indian courts.

In 2021, Antrix went to the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT), Bengaluru with an interesting request — it said that Devas was created for running fraud, and asked that the company be wound up. The NCLT found exactly that. It decided that Devas’ very legal existence would be dissolved. Devas appealed this all the way to the Supreme Court, but it, too, endorsed this finding. Fraud vitiates everything, it held. If the original contract was fraudulent, then any arbitration award based on it was also tainted.

Based on this, the Delhi High Court invalidated the original arbitration award in August 2022. It’s reasoning was blunt — if you enforced an award based on a fraudulent contract, that would “perpetuate the fraud”. From India’s perspective, this was a righteous cleanup operation — protecting taxpayers from having to pay for a corrupt deal.

Meanwhile, after trying and failing to get the founder of Devas, Ramachandran Viswanathan back to India, a special court has declared him a ‘fugitive economic offender’ — a tag reserved for the likes of Vijay Mallya and Nirav Modi.

As things stand, courts in India and abroad see the same issue in opposite ways. On one hand, there’s a finding by an international arbitration panel, that India owes $1.3 billion to Devas. Courts all over the world have honoured this finding. On the other hand, India’s highest courts have held that Devas’ very existence is nullified, and that award has no meaning if it’s pushing a fraud ahead.

Legally, this case is a complete nightmare. But let’s get back to the US Supreme Court.

US Supreme Court 2025

The latest chapter in this showdown came at the US Supreme Court, last week. The legal question was highly technical: did Antrix need a strong connection to the United States to be sued there? This bit of legal pedantics was, however, a billion-dollar question.

On June 5, 2025, all nine Supreme Court justices decided otherwise. It emphasized that the law clearly created a “comprehensive framework” for suing foreign governments. There was nothing in there about strong connections to the United States. Adding extra tests would “weaken the link Congress forged” and create gaps in the law.

Now, the Supreme Court’s holding is extremely specific. It doesn’t give finality over everything — it just kills a legal loophole that the Indian government tried to use. There are other approaches that the government can take, though there’s no guarantee that they would work either. The case now returns to the Ninth Circuit, where Antrix will have to deploy other defenses.

But when you zoom out, it points to the sheer mess that a single contract can land us under.

The Anatomy of the Sovereign Risk Nightmare

The Devas-Antrix saga is a masterclass in how small problems can turn into massive liabilities.

To anyone seated abroad, it looks like India is making its legal strategy up as it goes. What started as a relatively simple space deal — the kind of thing India has just approved for Starlink — kept turning uglier year-after-year.

Instead of a pioneering space industry, we got an abrupt policy change, which turned into allegations of fraud, which ended in attempts to dissolve the company altogether. Meanwhile, India has been running from pillar-to-post trying whatever legal strategy could work in courts across the world. By contesting every award and appeal, India allowed compound interest to balloon a $562 million judgment into $1.3 billion — roughly eight times the original spectrum value. The 18% annual interest meter is still running, adding millions each month to the tab.

Was Devas actually a fraudulent company built to rip India off? We don’t know — and we won’t know for sure, at least as things stand.

But it paints a sorry picture. While we pitch India as a stable, rules-based investment destination, our conduct in the case has become a case study in sovereign risk management programs worldwide. All this reputational damage — over a contract worth a few hundred crores.

Understanding India’s shrimp industry

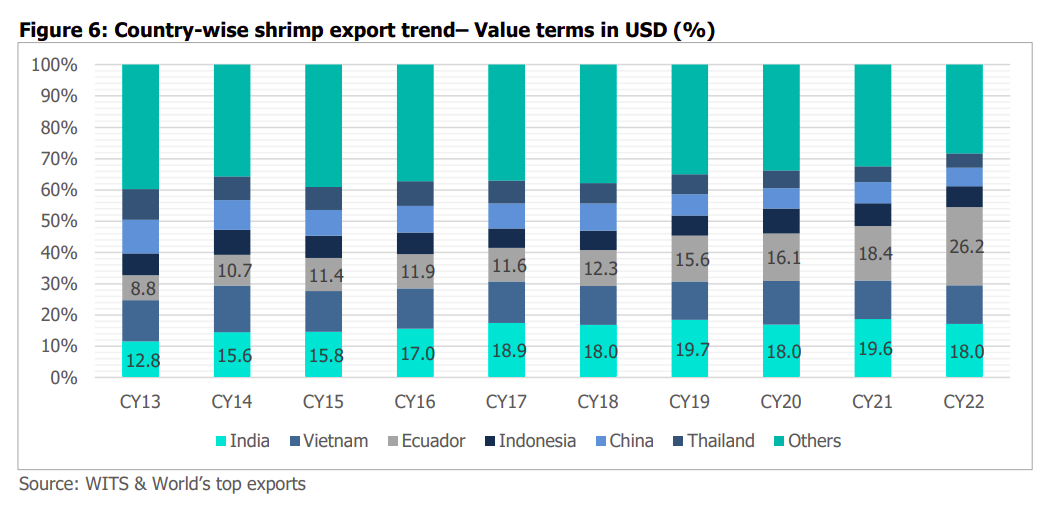

Today, we are looking at the shrimp sector. We never really went into this space before, so our understanding before writing this piece was honestly non-existent. But from what we’ve read, this is one of those rare industries where India is vying for global leadership.

We’ll get into the Q4 results of two listed companies in the space — Avanti Feeds, which is the largest shrimp feed manufacturers in the country, and Apex Frozen Foods, one of the largest shrimp exporters. But before we get there, we need to first get the lay of the land. Because once you scratch the surface, things get really interesting — from court cases to disease.

Understanding the shrimp business

Let’s start at the very beginning.

So, what even is shrimp farming?

When we say ‘shrimp’, we’re talking about these little guys who live underwater:

Yeah, there’s a whole industry around farming those little creatures.

What does farming even mean, when it comes to animals? Well, we’re growing shrimp in ponds instead of catching them from the sea. It’s a part of what’s called aquaculture — basically the aquatic version of agriculture. In India, most of this shrimp farming happens in saline ponds near the coast — especially on the eastern side of the country.

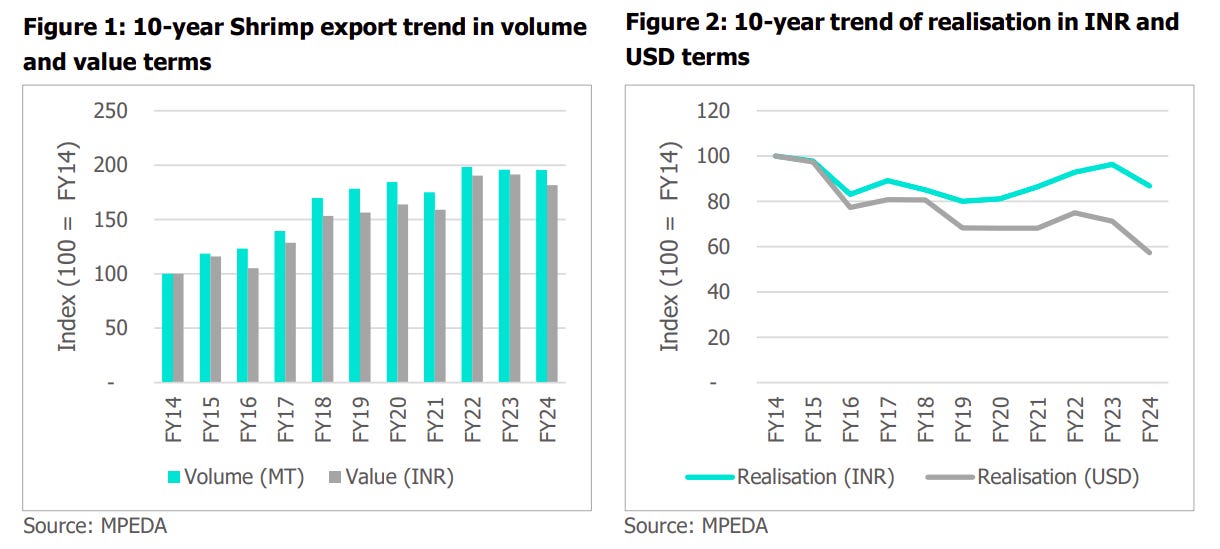

Today, farmed shrimp completely dominates over shrimp fishing. The stuff we catch from the sea — what’s called wild-caught shrimp — is only a small fraction of what we produce. And we eat very little of it. Almost all our shrimp is exported.

To give you a sense of the numbers: In FY24, India exported seafood worth $7.38 billion — and frozen shrimp alone accounted for about 66% of that value, making it by far the most valuable export item in the seafood basket.

But this wasn’t always the case

India’s shrimp story really began in the 1980s and 1990s. Back then, the dominant shrimp species was something called the black tiger shrimp, which is native to India. Farmers started cultivating it in coastal ponds, and demand — especially from Japan and the U.S. — took off.

But this early boom came with serious problems. Farms started popping up all along the coastline without regulation. They often destroyed mangroves and polluted nearby water bodies. It got so bad that in 1996, the Supreme Court banned shrimp farming in sensitive coastal areas through a landmark case — S. Jagannath vs Union of India. That one judgment stalled the industry for a while.

But eventually, it led to the formation of the Coastal Aquaculture Authority (CAA), which still regulates shrimp farm licensing today.

Meanwhile, there was another problem. Disease.

The disease that wiped out entire farms

By the early 2000s, black tiger shrimp farming was struggling. A virus called White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) kept hitting farms. Infected shrimp would die off in just a couple of days, wiping out entire ponds. Farmers were spooked. Some quit altogether. And the industry hit a wall.

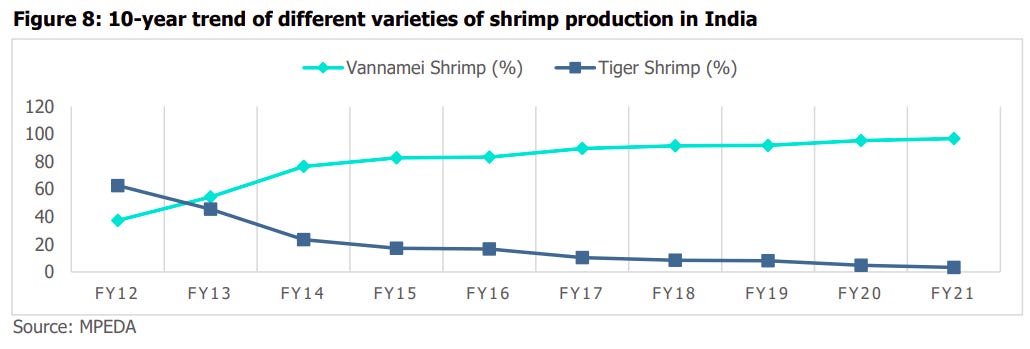

Then came the big turning point: Vannamei.

In 2009, India allowed the cultivation of Litopenaeus vannamei, also known as whiteleg shrimp. This species wasn’t native — it came from the Pacific coast of Latin America. But it had a few key advantages. It grew faster. It was cheaper to farm. It could be stocked at much higher densities (30–60 shrimp per square metre)

But most crucially, it was Specific Pathogen Free (SPF)

That SPF tag meant that the parent shrimp — called broodstock — were certified to be free of major shrimp diseases. Not genetically modified; just carefully bred in biosecure facilities (usually in the U.S. or Mexico) and tested repeatedly to ensure they were clean. India started importing these broodstock, and hatcheries began spawning them to create billions of baby shrimp — or post-larvae — for farmers.

That changed the game, and the industry exploded.

Okay, so how does the value chain actually work?

You start with broodstock. These are adult, disease-free shrimp imported from overseas. Think of them as the grandparents. They’re not farmed for food — they’re kept in secure tanks at hatcheries to breed.

Then come the hatcheries. This is where the broodstock lay eggs. These eggs hatch into larvae, and after 15–20 days, grow into post-larvae (PL) — essentially baby shrimp. These PL are then sold to farmers at ₹250–500 per 1,000 PL.

Farmers buy these baby shrimp and stock them in farms — open ponds, usually 1–2 acres in size. They feed them with commercial ‘shrimp feed’ — a mix of fishmeal, soy, and nutrients. The shrimp grow over 90–120 days.

Once they hit the desired size — say 30–50 shrimp per kg — they’re harvested and sent to processing plants.

In these plants, they’re cleaned, peeled, frozen, packed, and exported to markets like the U.S., China, and Europe.

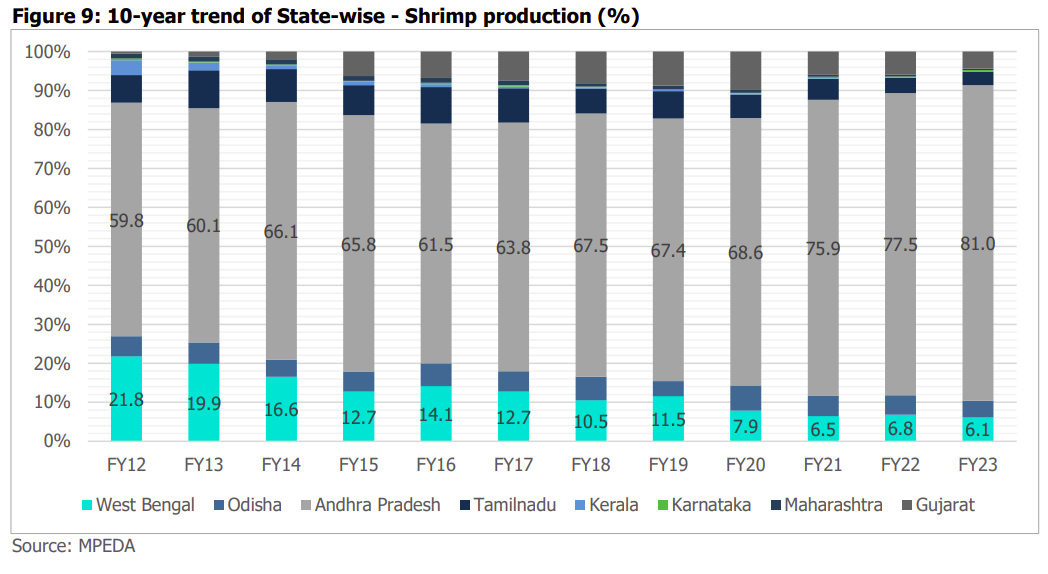

This whole supply chain has thousands of smallholder farmers, especially in Andhra Pradesh — which alone accounts for over 60% of India’s shrimp production.

How much money does the industry make?

Let’s break it down.

Shrimp farmers basically have to feed shrimp, and ensure that nothing kills them. Their biggest cost is feed — around 45-50%% of total cost. Other big costs include electricity (for aerators), post-larvae seed, water quality treatments, and labour.

How much do they earn? That’s a question of how many shrimp survive, how well they grow, and how the markets are. This gives us three key metrics:

Survival rate (how many shrimp make it to harvest)

Feed conversion ratio (FCR) (how efficiently the feed turns into shrimp mass)

Market price (which swings based on global supply and demand)

In good times, farmers can make decent margins — especially with large shrimp (like 30–40 count per kg). But occasionally, the market sees a downturn — like in 2023, when prices crashed. Suddenly, margins fell to as low as 5–6%, and many farmers skipped a crop entirely.

Meanwhile, processors run a bulk business, running on thin, single-digit margins. They’re often making a razor thin 4–7%, but at high volumes.

With all that context, we’ll look at 2 companies: Avanti Feeds and Apex Frozen foods.

Avanti Feeds

Avanti Feeds is India’s largest shrimp feed manufacturer — with around 50% market share.

Last quarter was a mixed one for the company. Its margins bounced back from previous lows, with feed carrying the weight of its business. Exports, however, got bruised by duties. Agility and timing carried the company through this phase.

What business are we looking at?

Avanti’s feed business is largely tied to the health of India’s aquaculture industry—especially shrimp farming.

Farmers rely on companies like Avanti to supply protein- and carbohydrate-rich feed made of ingredients like fish meal, soybean meal, and wheat flour. When raw material prices soften, margins expand. When climate, disease, or input costs get tricky, volumes and margins take a hit.

Shrimp feed is Avanti’s cash engine, and in FY25, it benefited from both higher volumes and easing input costs. But the company also has a processing segment, which deals with cleaning, freezing, and exporting shrimp to countries like the US and Japan. This saw higher volumes but lower profitability, thanks to a complicated tariff story.

So how did Avanti perform in Q4 FY25?

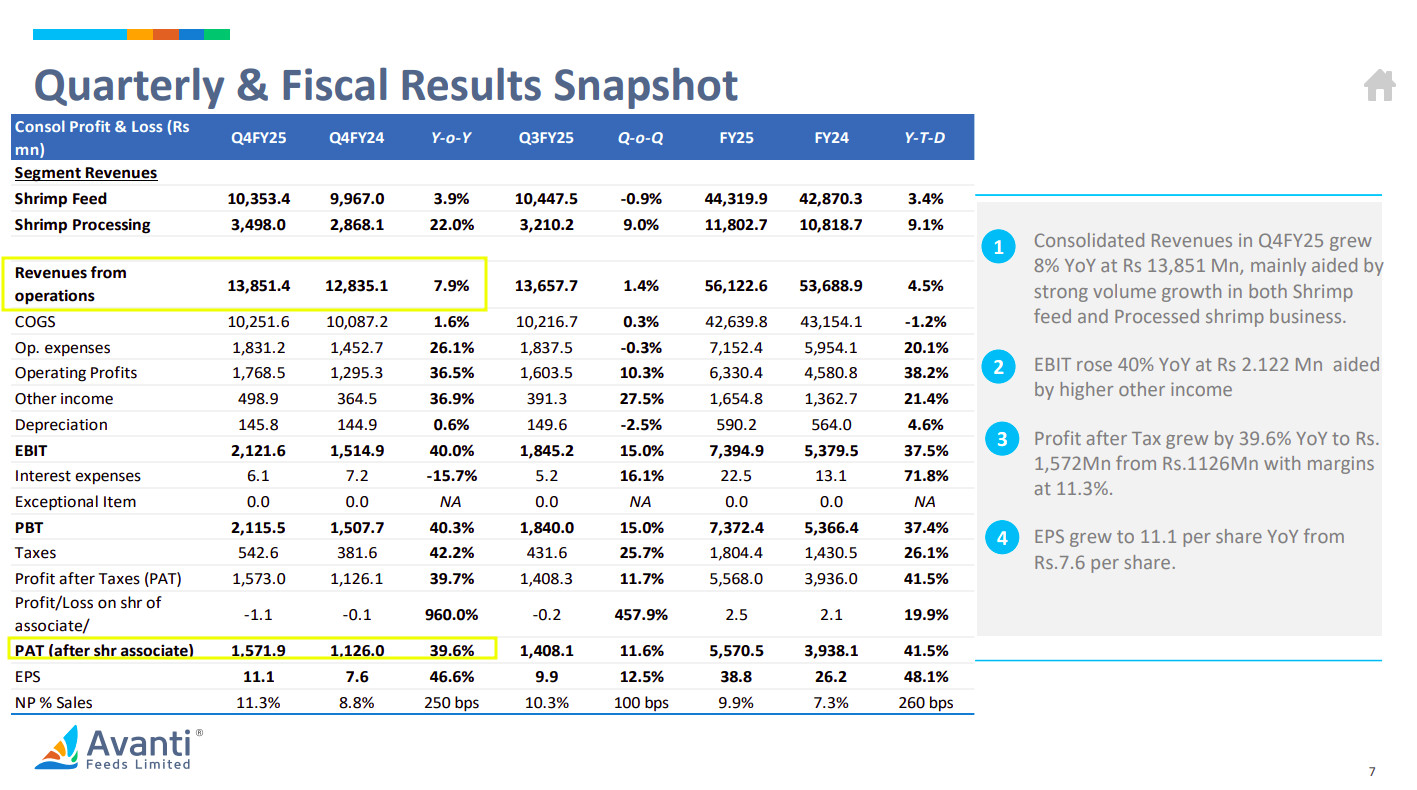

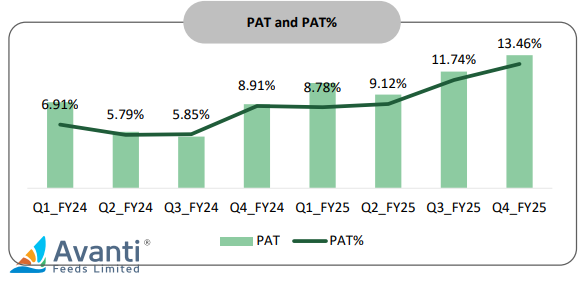

At a consolidated level, Avanti’s revenue grew 8% YoY to ₹1,385 crore. But much more of that turned into profit than a year ago. Its PAT was of ₹157 crore, up around 40% year-on-year.

The star of the show? Feed.

Last quarter, its revenue from feed was up marginally — ₹1,035 crore, up from ₹996 crore last year. The company also did decent volumes, of 1.30 lakh MT, slightly higher than last year. This is a good sign. Despite weather and disease challenges in aquaculture, demand remains stable.

But the real story lay in the segment’s sheer profitability. The company saw both its profit and its profit margins grow

This was primarily driven by a drop in key input costs. Fishmeal prices fell to ₹91/kg (from ₹99), and soybean meal prices fell to ₹43/kg (from ₹52). On the other hand, the company also has to pay for wheat flour. And those rates are linked to the MSP. Those costs moved up slightly.

As its management said:

“The softening of fish meal and soybean meal improved profitability. But with the MSP hike, we’re already seeing some price firming. It’s a volatile basket.”

But the processing business is telling a different story

Here, the numbers are more nuanced. The company’s revenue rose to roughly ₹350 crore from ₹287 crore YoY, a 22% jump, backed by higher volumes and better realization. But its profitability took a hit. The company’s EBITDA margins fell to 7.6% from 13.7% last year.

Why the sudden decline? It was a mix of America’s tariffs, the increase in freight costs. Both, together, inverted how its business looks. As per its management:

“Earlier, processing gave us better margins than feed. But with these duties, that’s flipped. Now feed is more profitable.”

Still, they’re not exiting the game. In fact, they’re doubling down on value-added shrimp products — like peeled, cooked, or tail-on formats — that command better pricing and face less competition from low-cost exporters like Ecuador. As its management says:

“Ecuador is cheaper, yes. But they can’t match us in medium value-added formats. That’s our strength.”

Tariff trouble and the export workaround

India’s shrimp exports to the US now face one of the highest effective duties — 33.12% — when you combine anti-dumping, countervailing duties, and the recent 10% reciprocal tariff introduced in April 2025. This sudden jump could well have killed the average export-oriented business. But here’s where Avanti showed its agility.

“We proactively informed our US customers and passed on a 10% price hike. Most accepted. We also pre-shipped large volumes before the new tariffs hit.”

Somehow, the company maintained sales growth in Q4 despite the adverse policy environment — largely by seeking out new customers. But they’re also aware that this can’t go on forever.

“We’re pushing hard to diversify to Japan, Korea, EU, and the Middle East. We can’t remain overly dependent on the US.”

Is there any respite in sight? Its management hinted that US-India trade talks are advancing, and if duties get relaxed — even partially — it could provide significant upside.

Apex Frozen Foods

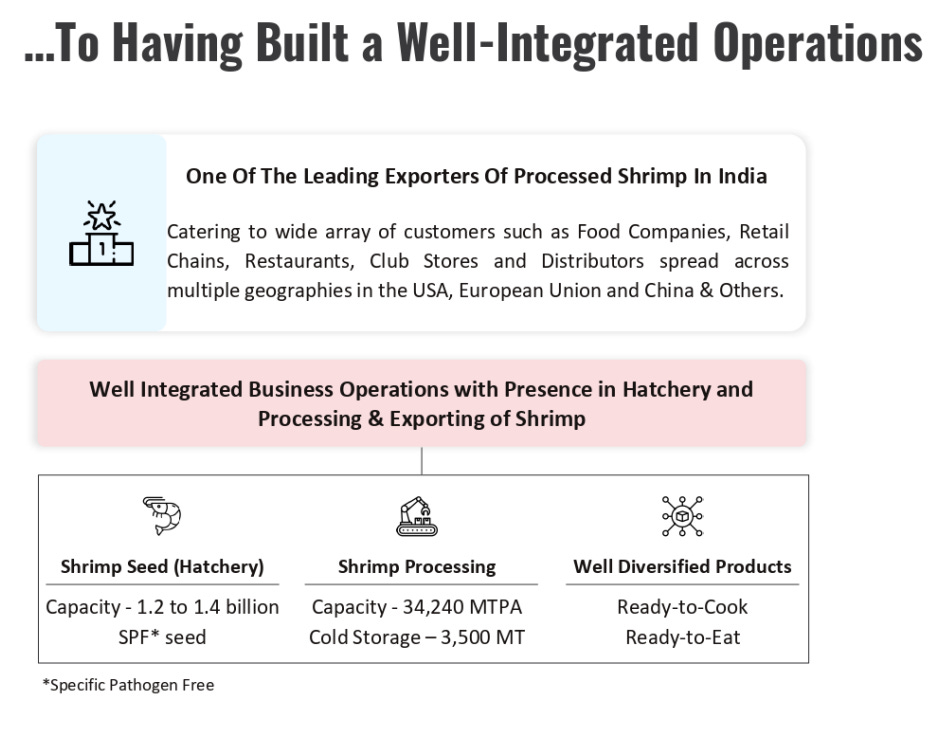

Apex is one of India’s leading exporters of processed shrimp. Unlike players that do only one part of the value chain, Apex is fully integrated — they produce shrimp seed (hatchery), handle farming and processing, and then export the final product.

Their facilities, mostly based in Andhra Pradesh, are located close to key shrimp farms and ports like Kakinada and Vizag. They have two processing plants with a total capacity of 34,240 metric tonnes (MTPA), including a growing share of ready-to-eat products.

Apex isn’t just selling plain shrimp. It’s among the few Indian companies with a serious push into value-added shrimp offerings, like ready-to-eat items. They’re growing this aggressively. In FY25, 26% of their total volumes were RTE — up from 15% in FY21. This move up the value chain is interesting. Margins in basic shrimp exports are thin and volatile. Apex is trying to break out of that trap.

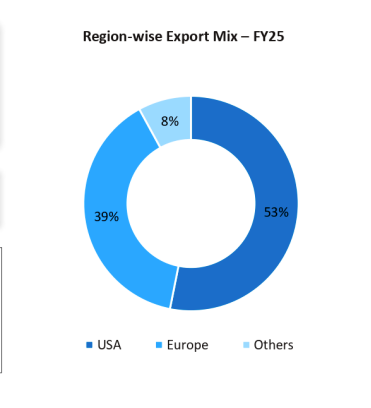

In terms of geography, the US is still their biggest market (~53% in FY25), but the European Union has become a fast-growing second engine (~39% now, up from 26% last year).

So what happened in Q4?

Q4FY25 was a quarter of recovery for apex.

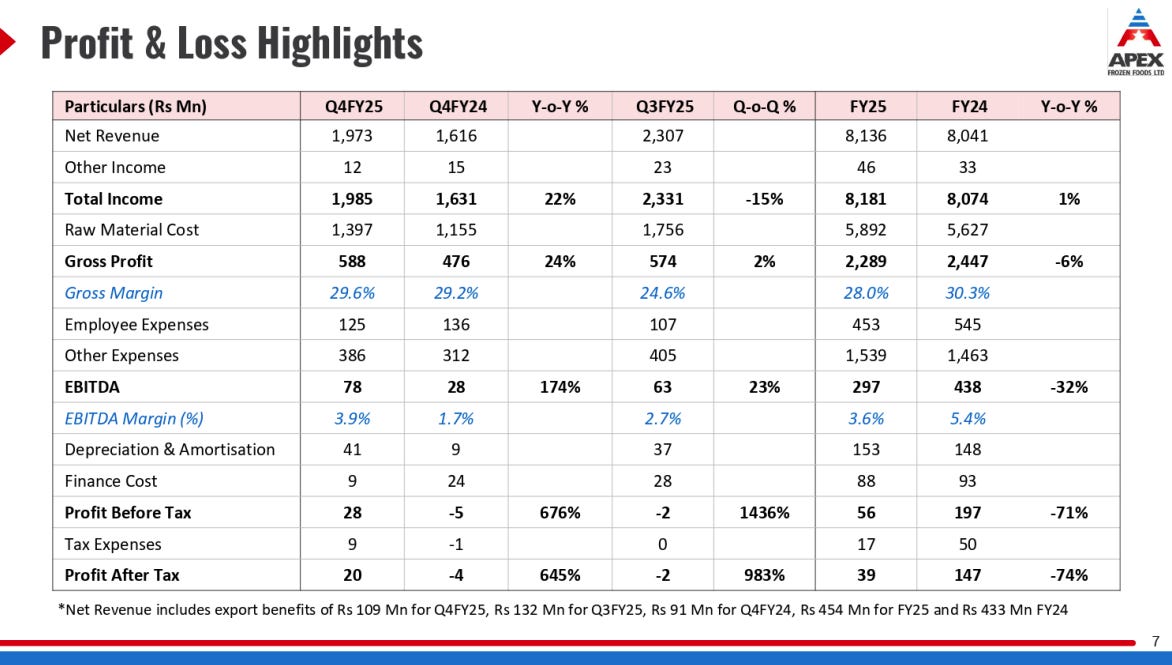

Its revenue rose 22% YoY to ₹197 crore. It’s a big jump, but that’s nothing compared to its profitability. Its EBITDA jumped an incredible 174% YoY to ₹7.8 crore. And that turned the company profitable: its PAT swung from a loss of ₹4 crore last year to a profit of ₹2 crore.

What helped?

The company started earning more on its sales. Its average shrimp selling price was ₹794/kg, up 20% YoY and 6% QoQ. EU sales, in particular, boomed: shipments to Europe rose 70% YoY in Q4, and now form a solid 39% of annual sales — up from 26% just a year ago.

Meanwhile, at the other end of its operations, Apex also benefited from lower raw shrimp prices, which dropped 4% QoQ to ₹358/kg.

Essentially, it paid less for its inputs, and was paid more for its sales. Its gross margins, as a result, become much more comfortable.

Reasons for hope?

Let’s start with the strategic shift. We’ve told you about Apex’s move towards higher-margin ready-to-eat products. But they’re running into a problem. One of their processing units, which handles ready-to-eat products, hasn’t yet received full approval from the EU. As a result, they’re locked out of selling their most profitable products into one of their fastest-growing regions.

But that might change soon. As MD Karuturi Chowdary said:

“We are just awaiting [EU approval] anytime soon. The moment it is done, it paves way for us to grow our Ready-to-Eat business… especially in our second largest market.”

This could be a game changer for the company. It can pump out 10,000 MTPA of ready-to-eat items. Once the EU approves this plant, Apex expects to add 2,500 MT of extra volume in the first year alone. That could add massively to their margins.

You can see a similar upward trajectory elsewhere. They’re finally done with legacy issues—old bad debts, customer churn, and provisioning. Over FY23 and FY24, they lost business to Ecuador and Vietnam. But they’re recovering — they have now regained some lost U.S. clients while also expanding in Europe. As Chowdary put it:

“We believe we have come out of the negatives… [and] we are done with all those legacy issues which were hanging in the company.”

Tidbits

JK Cement Acquires 60% Stake in Saifco Cements for ₹150 Crore

Source: Business Line

JK Cement Ltd has acquired a 60% equity stake in Srinagar-based Saifco Cements at a total consideration of ₹150 crore. Saifco operates an integrated cement plant in Khonmoh with a clinker capacity of 0.26 MnTPA and grinding capacity of 0.42 MnTPA. The company reported a turnover of ₹73.17 crore in FY25. As part of the deal, JK Cement will assume management control and nominate three out of five board directors. The investment includes payments made both to the promoters and into the company. This move marks JK Cement’s first manufacturing presence in the Kashmir region. The acquisition aligns with the company's broader strategy to deepen its footprint in the northern markets. JK Cement’s existing grey cement capacity stands at 24.34 MnTPA, making this a relatively small but regionally strategic addition.

Govt Raises Onion Cost Recovery Benchmark to 72% Amid Buffer Stock Push

Source: Mint

The government has increased the onion cost recovery rate to 72% for the current rabi season, up from 65% last year. This means private contractors storing onions under the central buffer scheme must ensure that 72 kg out of every 100 kg remain marketable post-storage. The move is part of efforts to build a 500,000-tonne buffer stock for price stabilization, with NAFED and NCCF overseeing procurement. Private players have been brought in to procure, store, and transport onions, with staggered payments and provisions for incidental costs. The higher threshold aims to reduce spoilage, improve accountability, and curb supply-side manipulation often cited by traders. While this step enhances operational efficiency and may help in controlling retail price volatility, it does not directly benefit farmers, who typically sell before the storage phase.

Tata Steel to Begin Low-Carbon Project in UK by July

Source: Business Line

Tata Steel is set to commence construction of its electric arc furnace (EAF) project at Port Talbot in July 2025, aiming to begin operations by 2027. The project is backed by £500 million in funding from the UK government. This marks a strategic shift from traditional blast furnace-based steelmaking to a low-emission model using locally available scrap. As part of the transition, Tata Steel has already shut down its heavy-end operations in the UK and is currently meeting demand through imports from India and the Netherlands. The company plans to reduce its fixed costs in the UK from £762 million in FY2024–25 to £540 million in the following year. Cost rationalisation will be driven by optimisation of substrate sourcing, IT infrastructure modernisation, downstream rationalisation, and a cut in corporate overheads. Planning approvals for the project have been secured, and the structural transformation is aimed at aligning operations with evolving market and environmental expectations.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Apoorv and Krishna.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

both the stories were great, good write up and keep it up. looking ahead for such similar stories

Fascinating read! I’m Harrison, an ex fine dining line cook. My stack "The Secret Ingredient" adapts hit restaurant recipes for easy home cooking.

check us out:

https://thesecretingredient.substack.com