In mining, uncertainty rules over all else

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Understanding mining II: Investment under uncertainty

How did Indian banks perform this quarter?

Understanding mining II: Investment under uncertainty

We began this year with a slightly different episode by our standards. We gave you a geological history of India, and the fascinating origins of the lands we live on. Some of you liked what we did. But many of you were left wondering why we were giving geography lessons.

Here’s why: imagine you ran a mining business, with rights over a large plot of land. Except, a lot of it is just mud and useless rock, and very little of it has valuable minerals that you can sell. How do you even know what your business is worth?

This is a fundamental problem. When you’re bidding for mining rights over a patch of land, you’re paying for an inventory of goods to sell. Only, you don’t know how big that inventory is. You don’t get to order any more either. There’s an element of faith to the business; any commercial decision around taking over a mine is made under deep uncertainty.

This makes any information on what you might find under the ground deeply valuable. In fact, long before you start extracting any resources from the ground, years are spent trying to estimate what you’ll find underneath.

Conversely, without enough information, even a mine with exceedingly valuable resources could seem unattractive. If you follow the financial news, you’ve probably seen many reports around failed mine auctions — with the blame pinned on “poor response”. Often, these failures aren’t because the rock itself is unattractive, but because we tried selling those blocks without knowing enough about them.

The value chain of building certainty

When the process of finding resources begins, you’re essentially trading in geological rumours. One can only make calculated assumptions that the ground could yield something valuable. Over a series of attempts at data collection, you narrow your estimates until you have a deep sense of what a mine could yield — within 10-15% of what is actually available.

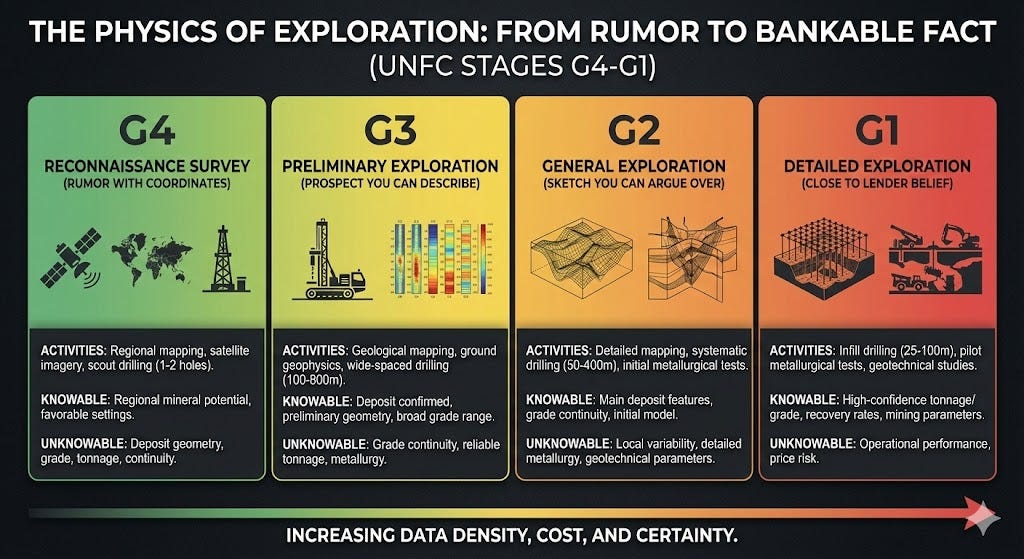

To understand this better, thankfully, there’s a framework one can use: the United Nations Framework Classification (UNFC), which India signed in 2003. It breaks this process of assessment down into four stages — from G4 to G1, as our data density improves.

G4: Reconnaissance

At this early stage, one has little more than a well thought-out estimate. You might have satellite imagery, for instance, which tells you whether the lay of the land will help you or not. You might even have found tiny rock samples in a stream nearby that could carry valuable resources. But there’s nothing you can say with certainty, yet. All you know is that you’re interested.

G3: Preliminary exploration

If the results of G4 are promising, you want to dig deeper. Now, you want to confirm if your hunch is correct; if there’s actually a deposit, and if so, how far it stretches. You also want to know how good the ore quality could be.

So, you start exploring the area systematically. You start drilling a series of holes into the ground, with wide spaces between them. For some minerals, these might be 100 meters apart; for others, 800 meters apart.

Drilling gives you large “columns” that you can study, to get a sense of what’s underneath the ground.

You don’t yet know what that entire patch of land holds. But now, you at least have a sense of what lies underneath a few points across that land, even if those points are a few hundred meters apart. You also now know the grades of ore you might find underneath.

From this, you can begin to infer the deposits you might find. But the assumptions aren’t yet over. The drill-holes are as far as half a kilometer apart — and there could be anything in between. It’s still too early to guess at what it might be worth, or what it might cost to pull it all out. But you know there’s a mass of ore underground.

G2: General exploration

If the G3 test passes, you double down.

You start drilling holes a lot closer — between 50-200 meters apart, based on what you’re looking for. At this stage, you’re trying to get an accurate sense of the major geological formations under the ground, and what you might find useful. You also start testing samples in a laboratory, to understand how hard it’ll be to process that ore.

This is when you can begin forming estimates of the economics this site might entail. These estimates aren’t very accurate — you should expect at least a 20-30% error. You’re not sure if there are patches in between where the ore quality drops, or if the body of ore twists or slops in a way you didn’t expect. But you’re getting there.

G1: Detailed exploration

And at last, the G1 stage. Now, you’re no longer just prospecting. You want certainty to fine-tune investment decisions.

You increase your drilling density once more — maybe every 25-100 meters. But you’re not just looking at ore quality now. You’re carrying out large pilot tests. You’re also trying to understand the constraints you might run into — things like where groundwater might be, or if the soil is too weak to hold as you mine. It is only now that you have proven reserves, with a high degree of confidence.

If all goes to plan, this is when you actually begin operations — having spent hundreds of crores, and years of your time. And if you do begin operations, you’ll be spending a lot more.

Who bears the risk?

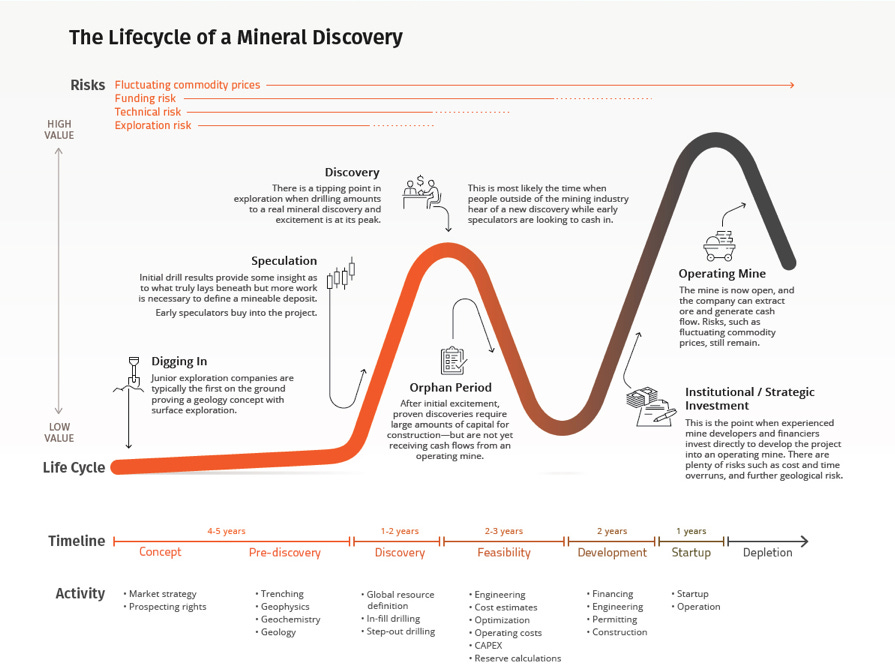

Before a mine sees its first Rupee in revenue, there’s a long gestation period where you keep spending ever-larger amounts just to create certainty. Who foots that bill?

There are, broadly, two choices a country can make. One, the government spends heavily on exploration, and then sells bankable mining sites for a high cost, recouping that investment. Two, the government steps away completely — making exploration easy for private entities, letting them scope out a large number of promising sites, while finding a business model that compensates them for that risk. The former creates certainty; the latter, abundance.

India made a third choice: where the government becomes a bottleneck to exploration, but auctions sites pre-maturely. This is the worst of both worlds.

Indian mine licensing: a brief history

Before 2015, India had an ad hoc system for granting mining leases: we gave out “prospecting licenses” on an opaque, first-come-first-serve basis. This was an open door to corruption — ruining the reputation of the entire sector.

But it had one lone benefit: private companies would spend their own risk capital in trying to find new deposits — with the hope that if they succeeded, they would reap the revenue.

In 2015, the government created a more robust set of procedures: under the Minerals (Evidence of Mineral Contents) Rules, 2015 (or MEMC Rules). Now, all preliminary exploration would have to start with the state. The pipeline of all future mining in India would be created by state entities, like the Geological Survey of India (GSI), and the Mineral Exploration Corporation Limited (MECL).

Private miners would only come in at this point: through a competitive auction. The government would issue two types of licenses. If a site reached the G2 level, it could auction off “mining leases” — 50 year permits to extract resources. If a site was still at the G3 or G4 level, however, it could still give out “composite licenses” — where a miner would get seven years to complete prospecting, and if they wanted to proceed thereafter, could convert it to a mining lease.

In 2023, the government also introduced “exploration licenses”. We’ll get to those shortly.

Where it all breaks down

It isn’t easy to create a pipeline of new mining projects. Most sites that look promising actually have very little commercial value. Finding this out, however, is a complex and expensive affair. Across the world, less than one in every thousand sites make the entire journey from reconnaissance to operations.

This is a job that was poorly suited for entities like the GSI. They were not designed to run repeated, capital-intensive drilling projects. And moreover, there are simply too many bureaucratic obstacles to cross. They cannot risk hundreds of crores of taxpayer money on high-risk drilling campaigns that might yield zero returns.

This creates a bottleneck at the very top. Since the MEMC Rules came into force, new exploration slowed to a trickle. The pipeline of new projects was choked at the very beginning.

This was, in fact, why India eventually introduced exploration licenses: giving rights to private entities to carry out preliminary exploration instead. But unlike other countries, in India, these are state contractors. If they successfully find resources, they can’t monetise those successes — they must immediately surrender those to the government. At least so far, this hasn’t led to an outpouring of fresh projects.

But imagine a site does make it to auctions.

Few sites, if any, are well-explored at this point. They’re almost never at the G1 level. As The Energy and Resources Institute notes, their estimates are often subjective and error-prone. Meanwhile, bidders aren’t allowed to conduct their own surveys either before an auction. In essence, they’re asked to bid hundreds of crores on the back of, well, an erroneous PDF file. Naturally, they’re rarely confident enough to bid, often sitting bids out.

At the same time, these auctions are priced in a way that emphasises on revenue generation, not efficient development.

Any bid must account for a host of fixed costs. This includes royalties to the state government — which are already among the world’s highest. Then come the amounts bid for. The bidding process doesn’t even account for how hard a mineral extraction process is. The government simply assigns an “average sale price” for the mineral, and bids are solicited as a percentage of that.

Consider, for instance, the Reasi Lithium reserve — supposedly the answer to our green transition. The lithium there came mixed with clay, and separating the two was something that had never been attempted. And yet, auctions were announced at the G3 level itself. Unsurprisingly, it failed.

Successful auctions, too, can end up wildly overpriced. In one extreme case, for instance, for iron ore in Madhya Pradesh’s Pratappura went for 275% — or nearly thrice — of the resource value.

There are other issues we don’t have the space to go into, here — from the lack of coordination of granting licenses to the winning bidder, to a “winner’s curse” which forces many successful bidders to give up their mines. The net result of it all is inefficient commercialization of what mines we do have.

And the mining hasn’t even begun

Imagine you win a bid, however, and your commercial plans fall into place. Now, you actually have an inventory in place… on paper. Then comes the real work — of actually pulling those rocks out of the ground. That’s a long and complex process in its own right, with many issues, concerns and points of failure.

But for that, you’ll need to wait for the next part of this series.

How did Indian banks perform this quarter?

The financial results for the quarter ending Dec’25 are coming in. And we now have numbers from India’s four largest private banks. The largest, SBI, is yet to publish them.

Jokes aside, banking doesn’t usually change in a single quarter. And for the most part, this quarter was much the same as what we had said last quarter — barring a few very interesting exceptions. However, what helps is to zoom out and view the quarter as part of a much bigger story that’s been unfolding. We did one such story earlier this month while covering the RBI’s 2025 review of Indian banking.

Before we get into the why, let’s start with the headline numbers.

The big numbers

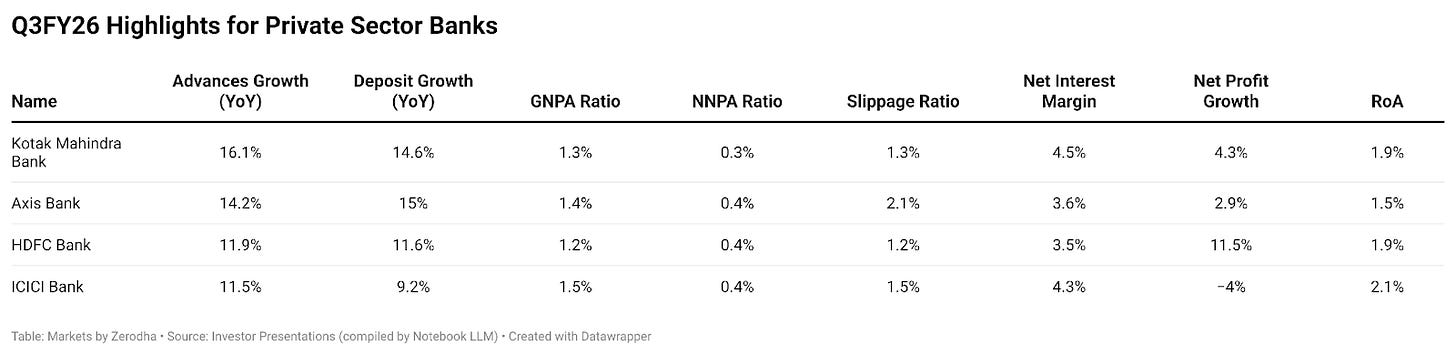

First, what did loan growth look like? It is mostly healthy across all the banks, with some differences.

Axis and Kotak have recorded much higher growth than their peers HDFC and ICICI, but that’s mostly because they’re coming off a smaller base. HDFC and ICICI, meanwhile, are stable anchors of Indian banking, growing at the industry average. But the headline loan growth number is not as interesting as the loan mix quality. We’ll return to this eventually.

Secondly, bank deposits, which are needed to sustain loan growth. On that front, Axis and Kotak put up strong deposit growth of ~15%. HDFC and ICICI are slower. Partly, that’s due to their sheer size. But partly, it’s also because across the system, deposit growth is not running comfortably ahead of credit growth. Banks aren’t really drowning in cheap money — if anything, the opposite might be more true.

If deposits do not keep pace with loan growth, banks resort to harder choices. One, they may borrow more from other places. Two, they could stretch their balance sheet harder against the same deposit base. Or lastly, they make deposit rates more attractive, causing a price war between banks, while also making their own cost of funds worse. We will also return to this later.

Third, margins. Net interest margins are still healthy, but they also look like they are no longer climbing.

That might partly be because of the new rate environment — in December 2025, the repo rate got cut. This creates a unique friction for banks. Yields on loans usually respond faster to a rate cut, falling immediately. However, deposit costs are slower to decline because fixed deposits roll off over time. So the bank’s income line adjusts quickly, while its funding cost adjusts slowly. This pulls margins down in the short-term for everyone.

Lastly, asset quality is still very clean. The headline GNPA numbers are roughly in the 1.2-1.5% zone. But that does not mean the quarter was free of noise. Some regulatory scrutiny and classification issues made their provisions jump. This, in turn, made reported numbers look messy even as borrowers paid on time. And that’s what we’ll be talking about next.

From “technical compliance” to a P&L item

Throughout India’s economic history, our banks have been mandated by the RBI to lend a portion of their portfolio to specific sectors (like agriculture) to help the country’s development. This is called Priority Sector Lending (PSL).

Now, the RBI is tightening the screws on how loans are classified. Earlier, banks would have given some loans for agri and categorized them as PSL. However, the RBI felt that banks had improperly classified these loans. So now, to reduce uncertainty from this mistake, it has asked banks to provision more money — if, in any case, these loans turn bad (even if they’re unlikely to).

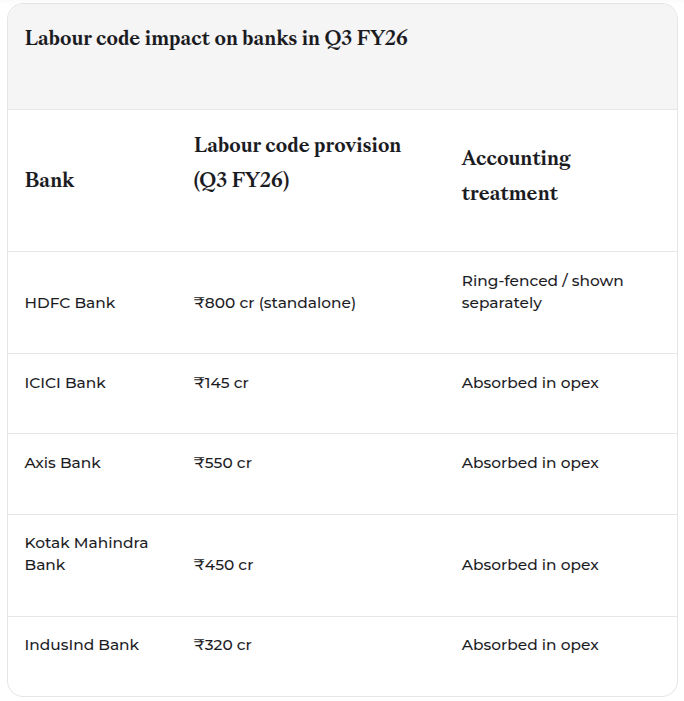

ICICI took the sharpest blow: a ₹1,283 crore standard asset provision on an agri-PSL pool for technical non-compliance. HDFC had the same pattern on a smaller scale: a ₹500 crore one-time agri-PSL compliance impact.

In the same spirit, labour code provisions also popped up across banks. These changes make it more expensive for companies to maintain the same level of workforce, since it increases the statutory requirements for them. This again, is a one-time impact hurting the banks.

The deposit problem is the whole problem

For most private banks, deposits are not keeping up with loans in a comfortable way. And there are no easy fixes to this problem. In Axis’ view, this is not a one-quarter mismatch that magically repairs itself. They think it may take around one-and-a-half years before deposit growth and loan growth start converging in a meaningful way.

Kotak, meanwhile, framed their deposit growth problem more broadly. A bank’s deposits don’t only get squeezed because customers switch to a competitor bank’s plans. It also happens if they decide to allocate more money to the stock market or commodities. In essence, the humble, stable savings account is competing with markets that feel more high-risk, high-reward.

HDFC admitted that they fell short of their own deposit ambition, and even said why. They didn’t want to pay up for bulk deposits at the prevailing market rate, even though they could have easily chosen to do so.

Each bank has a slightly-different view on the root of their deposit constraint, and their playbooks for solving this problem vary accordingly.

HDFC is trying to solve the deposit constraint the slow way, through distribution and customer stickiness. What they’re betting on is their older bank branches — as branches mature, they become far more productive over time.

And they provided evidence of this already happening in the earnings call. Their 5–10 year vintage-branches are doing 3-times the deposits compared to 5 years ago. Over 1,300 branches are moving into this higher-productivity bucket. Moreover, ~4,800 branches added in the last 5 years already contribute over 20% of incremental deposits.

In fact, for HDFC, even credit cards get framed as a deposit funnel and not just a lending product. That’s because card customers maintain deposit balances worth over 5 times what they spend on their card. This shows how every product is a way to deepen banking relationships.

Kotak, on the other hand, is being unusually explicit about making their deposits more stable. They are reducing interest rate-linked savings and pushing fixed-rate savings for their customers. This is a deliberate attempt to make deposits less sensitive to rate cuts, and also less volatile, even if it hurts margins.

Kotak’s savings account balances also look weaker for a slightly boring reason: some of that money hasn’t left the bank, but just moved places. Customers set a threshold, and once their savings balance goes above it, the excess automatically shifts into a fixed deposit that earns a higher rate. If the savings balance later falls below the threshold, money gets swept back from the deposit into the savings account.

So optically, savings accounts fall and the current-account-savings-account (CASA) ratio looks worse. However, the customer stays, albeit at a higher-cost.

In ICICI’s case, the deposit growth isn’t really weak because of retail customer stress. Much of the softness came from institutional savings balances, especially government-type floats (like a PSU’s bank deposits). These balances are usually huge in size, so when they drop, the headline deposit print looks worse than it actually is.

In all these cases, banks don’t seem to be brute-forcing growth in the mere quantity of deposits. After all, you can always gain more deposits by giving higher deposit rates and sacrificing margins — but that’s unsustainable in the long-term. Banks are prioritizing the quality and the deposit mix just as much, if not more.

Unsecured lending is being “managed,” while Corporate is the pressure valve.

Now, what about the quality and mix of bank loans?

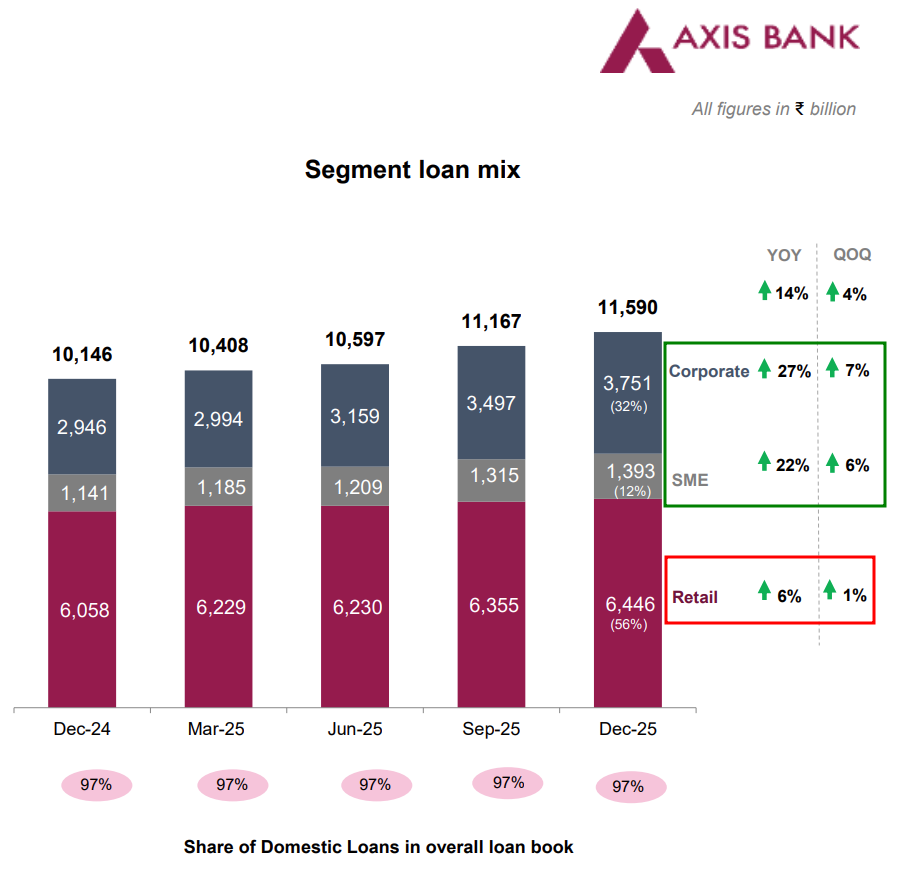

Well, there has been an ongoing shift from high-yield, higher-volatility loans to lower-yield, lower-risk ones. On one hand, risky unsecured retail loans, which aren’t linked to any collateral, are having their growth trimmed. Instead, other less-risky growth engines, like loans to corporates and SMEs, are being prioritized.

Now, unsecured retail is a high-return product when it behaves. The problem is that when it stops behaving, as it has, it does too fast for anyone to react on time. Since CoVID, banks had gone gung-ho lending to this segment, since it not only promised fat yields, but also high growth. But then the tide turned, as the risk of unsecured loan books became too big for the rewards it promised. This attracted the regulator’s keen eyes on the segment, too.

Banks would rather deal with this risk now rather than letting it show up later as a surprise. So, they’re acting early. They’re putting a cap on unsecured loan growth, tightening where they see early signs of stress, and growing other loan products.

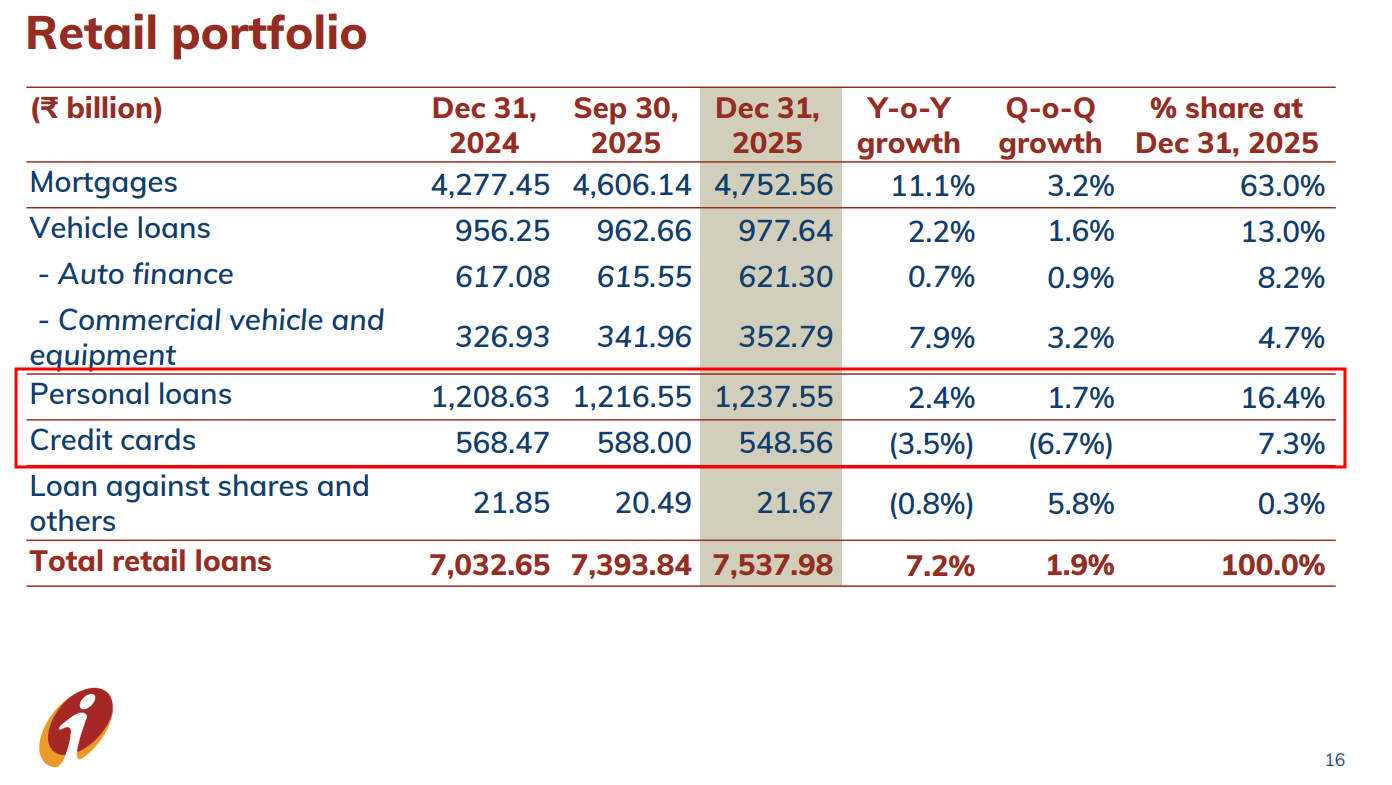

Take ICICI, for instance. Its credit card book shrank sequentially, and personal loan growth has moderated sharply. But that’s not demand disappearing. Rather, that’s ICICI limiting the supply of riskier loans at the peak of the cycle, especially when we have other growth engines.

Meanwhile, Axis has shifted growth away from retail loans and towards wholesale products sold to corporates and SMEs. They also explicitly linked part of the margin compression to this shift, a trade-off they seem to be okay with. They’ve taken lower-yield corporate assets, accepted a bit of margin dilution to keep growth going, and are evading a narrative problem in unsecured retail.

In Kotak’s view, their unsecured loan book does seem to be stabilizing. But the bank has also flagged specific stress pockets — like rural, vehicle finance, and microfinance.

The next quarter’s scoreboard

Nothing really broke this quarter, but the friction points got louder. On that note, what do we watch out for in the next quarter?

For one, the RBI’s rate-cut has still not fully transmitted through the banking system. Loan yields move first, while deposit costs lag. Q4 is where that timing mismatch will show up more honestly.

Secondly, does the noise from PSL compliance noise fades or continues to spread? It doesn’t really change borrower behavior but it does impact balance sheets. Ideally, as per most banks’ commentary, this should be contained.

Then, there’s bank deposits. The issue isn’t just growth, but also whether banks can add deposits without creating a price war. We’ll have to carefully watch the mix of funding and incremental cost of deposits.

Lastly, the mix of assets. Unsecured retail has taken a backseat, while less-risky loans to corporates are being pushed more. But we don’t know yet how permanent this shift is, or what more it entails. After all, if corporate loans keep growing, the banks should also strengthen their relationship with other companies, even create new fee pools with more cross-selling.

Tidbits

Electric two-wheeler companies are asking the government to extend PM E-Drive subsidies beyond March 2026. They warn that removing incentives could push prices up and slow demand, especially among first-time buyers. The industry says policy clarity is key to keep investments and expansion on track.

Source: Business StandardTCS plans to build a new technology campus in Brazil with a $37 million investment. The centre will serve clients across Latin America and is expected to create over 1,600 jobs over time. The move signals TCS’s long-term bet on the region’s growing tech demand.

Source: The Economic TimesAmazon revealed another round of global job cuts after an internal email was mistakenly sent to employees. The message suggested workers in the US, Canada and Costa Rica had already been informed. The layoffs appear to be part of Amazon’s broader cost-cutting push after rapid pandemic-era hiring.

Source: The Guardian

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Kashish

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉