Why Home Loans Aren’t Flying Anymore

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Is the best of Housing Finance behind us?

The importance of sending money home

Is the best of Housing Finance behind us?

Q3 FY25 results for Housing Finance Companies (HFCs) are out, providing a snapshot of the industry. HFCs generate revenue by borrowing at a cost and lending at slightly higher rates, but margins remain tight. Unlike credit cards with sky-high interest rates, home loans stay in the single digits (or slightly higher for affordable housing).

So, what really matters when analyzing HFCs?

Loan Growth Rates – Are they lending more than last year, and is the pace of growth slowing? Since charging high interest rates isn’t an option, growth depends on volume.

NPAs (Non-Performing Assets) – How many loans are turning bad? This number moves slowly because housing loans are long-term, and defaulting on them is often frowned upon in society.

Net Interest Margins (NIMs) – The difference between borrowing and lending rates. Margins are already tight, and this quarter, they’re getting even tighter.

We’ll take a quick look at three key players in the sector. But before that, here are two important trends shaping the industry: first, housing construction is slowing down, and second, raising funds has become more challenging.

The Housing Boom Is Losing Steam

Housing finance had experienced a strong growth streak after the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this was unsustainable, and it is now reverting to normal.

According to Knight Frank, sales and new launches in the affordable housing segment—once a major growth driver—have dropped in pace. The sector’s growth peaked in 2022 but has been slowing ever since.

Broader real estate numbers tell the same story. Anarock's data indicates that housing sales in the top seven Indian cities witnessed a marginal fall of 4% in 2024. When real estate slows, so does housing loan demand. According to RBI, Bank lending to homebuyers and HFCs has slowed, with home loan growth falling to 11% in 2024 (from 35% in 2023) and loans to HFCs shrinking to 2.7%.

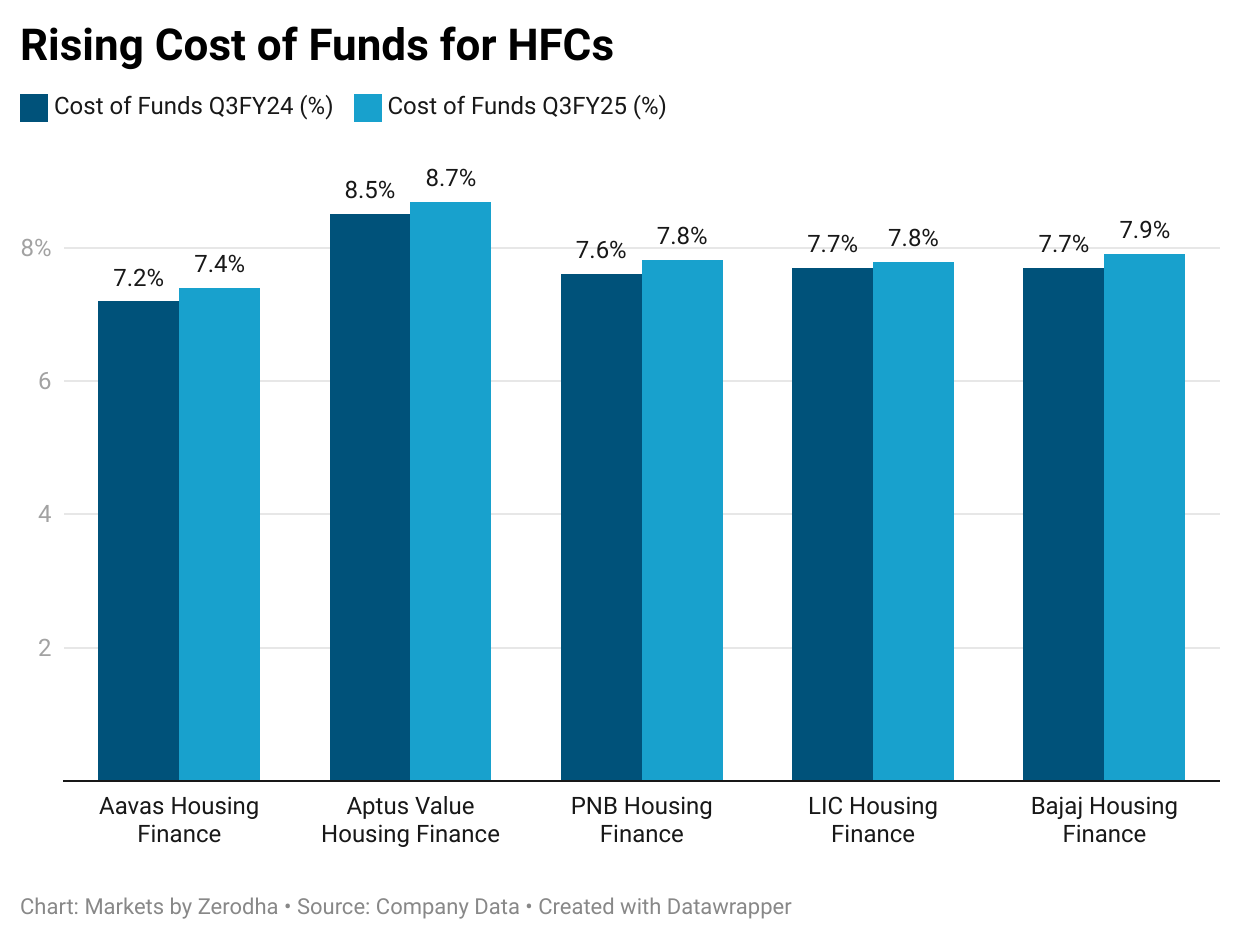

Slow but Steady Rising Cost of Funds

Despite stable interest rates, HFCs' cost of funds is rising — due to tighter bank lending. The RBI’s recent risk weight hike on NBFC loans made it costlier for banks to fund HFCs, forcing them to seek alternatives like NCDs and bonds. But that’s not really feasible for all NBFCs — it’s only big players who get easy access.

As a result, smaller HFCs are struggling, paying higher rates to attract funds. Every HFC we analyzed saw costs rise—Bajaj Housing Finance’s climbed to 7.9%, and Aptus Value Housing’s to 8.7%. Yet, home loan rates remain competitive, squeezing Net Interest Margins (NIMs). If interest rates drop but funding costs stay high, margins will shrink further, hitting profitability.

That’s what the sector looks like today. Now let us go deeper into a few company’s results.

Bajaj Housing Finance

This was the first full quarter for Bajaj Housing Finance since its listing last September.

The company posted a strong 26% YoY growth in assets under management, reaching ₹1.08 lakh crore in Q3 FY25. However, its RoE dropped to 11.5% (from 15%) due to the capital raised in its IPO, which temporarily increased equity. As leverage expands to 7-8x, RoE is expected to normalize at 13-15%.

Asset quality remains solid, with gross NPAs at 0.29% and net NPAs at 0.13%—slightly higher than last year but well-managed.

One of the biggest surprises in this quarter was the company’s rapid 57% YoY growth in its developer finance loan book. Developer finance refers to loans given to real estate developers to fund construction projects.

This growth came even as new project launches slowed across the real estate sector. It may seem counterintuitive, but it stems from Bajaj Housing Finance’s unique strategy—viewing developer lending as a feeder for its core home loan segment. By funding the construction of a project, the company secures the first opportunity to offer home loans to buyers of those properties.

Bajaj Housing Finance employs a "sweeps" collection strategy for developer loans. Unlike traditional models with long moratoriums, where repayment begins only after a project is completed, Bajaj requires small payments from the very first apartment sale. This ensures a steady cash flow, reducing the risk of a large default if sales slow down.

However, the success of this strategy will ultimately depend on how well NPAs are managed. Since developer loans are long-term, potential defaults may take time to surface. For now, it’s a high-growth bet, but its true impact will only become clear in the years ahead.

Bajaj is also expanding into the near-prime (₹30-50 lakh) and affordable (<₹30 lakh) segments, setting up a dedicated business unit. The focus is on new construction loans, targeting first-time homebuyers in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities across Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Rajasthan.

LIC Housing Finance

LIC Housing Finance's Q3 FY25 results show a company in transition — balancing falling margins and slower disbursements, cleaning up bad loans, and betting on affordable housing for growth.

One of the biggest challenges LIC Housing Finance faces is the pressure on its Net Interest Margins (NIM), which fell from 3.0% in Q3FY24 to 2.7% in Q3FY25. The biggest culprit? Its rising cost of funds, which has crept up to 7.7%.

To get around this, the company hiked its Prime Lending Rate (PLR) by 10bps in January 2025. This serves as a benchmark for interest rates on a wide range of financial products. It is, however, hard to judge whether this increased PLR would be enough to offset the margin pressure.

LIC Housing Finance has aggressively reduced its bad loans, bringing Gross NPAs down from 4.26% to 2.75% YoY. However, this improvement didn’t happen naturally. The company sold ₹510 crore worth of bad loans at a loss and wrote off another ₹174 crore.

Project finance remains a pain point, with 27% of loans in GNPA. Unlike Bajaj Housing Finance, which is expanding, LIC is cutting back on developer loans to reduce risk.

Its AUM growth is sluggish — at 6% YoY, it’s below industry trends, with ₹800-900 crore in loan disbursements, which were delayed due to property registration issues in Bangalore and legal hurdles in Hyderabad—though the former is now resolved.

If there’s one bright spot for the company, though, it’s LIC’s official entry into affordable housing. They have launched a new Strategic Business Unit (SBU) focused entirely on near-prime and affordable loans, similar to Bajaj Housing Finance.

These loans will be priced 250-300 bps higher than regular home loans, making them more profitable. But there is no lunch, high profitability comes with more risk of the possibility of higher NPAs. Keeping this in mind it aims to grow this segment to ₹25,000-30,000 crore in 3 years, making it 10% of its total loan.

Aavas Financiers

Aavas Financiers remains a pure-play affordable housing lender — unlike Bajaj and LIC, which are just expanding into this space. 80% of its loans are below ₹25 lakh, and 45% are under ₹15 lakh — where yields are 200 bps higher, making them more profitable.

Talking numbers, total loans (AUM) grew 20% YoY to ₹19,200 crore, showing strong expansion. New loan disbursements jumped 17% YoY to ₹1,600 crore, proving demand is still high.

However, Aavas too is hit by industry-wide problems: its margins are shrinking. NIMs fell 40 bps YoY to 7.54%, even after Aavas hiked its lending rates by 25 bps.

Why? Well, not all of Aavas’ loans got the higher rate yet – the PLR hike applies to new loans, but old loans are still given at lower rates. Moreover, Aavas is holding onto extra cash. They borrowed more than they lent, keeping a liquidity buffer. While this gives them flexibility, the fact that this money isn’t generating interest hurts their NIMs.

The standout thing for their business remains the lowest balance transfer (BT) outs in the sector at 5.4%. Customers seem to stick to the company instead of moving their business elsewhere — especially in Tier 3-5 cities, where competition is low.

One of the things highlighted in their results was the new core banking-based loan management system (LMS) that they launched. They claimed it has improved efficiency. The loan approval time went down by 30%, online disbursals up by 70%, and paperwork costs cut by 47%.

The importance of sending money home

We don’t live in an equal world. There are parts of the world — like our own country — where many people find it impossible to fund deeply important things, such as medical emergencies, or their children’s education. And then, there are other places where the average person earns as much as 30-40 times as much as an average Indian, and people consider themselves entitled by birth to all sorts of needs.

How do you bridge this gap? How do you ensure greater parity in the resources that people from wealthy and poor nations can access, without upsetting either? This is one of the world’s most complex economic questions. Experts spend years tinkering with foreign aid programs, loan channels, or investment agreements, all with the hope of finally perfecting some mechanism of wealth transfer.

And yet, one of the most effective mechanisms of global wealth transfer is something far more organic, decentralized, and largely ignored — remittances. That’s the big insight from a fascinating recent report by Our World In Data.

Broadly speaking, "remittances" refer to the money that migrant workers send back home to support their families. Collectively, global remittances amount to more than three times what all the world’s governments spend on foreign aid.

In fact, there’s some evidence that the world’s remittances are as significant as, or perhaps even more important than, foreign direct investment:

We’ve spent plenty of time on The Daily Brief talking about India’s foreign investment or international trade. Today, we thought we’d instead do a quick run-through of perhaps the most underrated channel of global wealth transfer.

Let’s dive in.

Who sends remittances, and who receives them?

Approximately 3% of the world — around 200 million people — lives outside their home countries. Many of these people regularly send money back home. In all, around 800 million people, or roughly one in ten people, depend on these transfers.

Of course, very few countries in the world are actually attractive enough to draw migrants. This gives a distinctly asymmetric pattern to international migration. 60% of the world’s migrants move to just 10 countries for their livelihood. These countries are uniformly rich.

And so, unsurprisingly, most of the world’s remittances flow from wealthy countries to poorer ones:

The specifics are telling:

The entire world aspires to move to the United States, and that shows up in the numbers. It constantly ranks as the single largest source of global remittances. In 2022, more than $79 billion left the United States in remittances.

More interestingly, however, the Middle East features prominently in this list. Saudi Arabia — which has long been a labor migration hub for South Asians and Africans — regularly features close to the top.

India has constantly received the largest share of global remittances, for well over a decade. In 2022, we broke the $100 billion mark, taking in $111 billion in remittances — a sum larger than the GDP of many smaller nations. Mexico is now the world’s second-largest recipient of remittances, followed by China.

That said, we’re a large country. In percentage terms, remittances are a relatively small part of our economy. There are other, smaller countries for whom remittances matter much more. In Tajikistan, Nepal, or Lebanon, for instance, remittances account for 25-50% of GDP. For them, migration isn’t merely important — it’s absolutely vital.

The outsized impact of remittances on households

Remittances are a particularly interesting channel for money flows.

For one, because of global differences in incomes and purchasing power parity, a little can go a long way. On average, migrant workers send a relatively small portion of their incomes — around 15% — back home. But this can be huge. 15% of the average American paycheck, for instance, is almost six times the income of the average Indian. These differences are so large that receiving remittances from abroad can completely change people’s lives back home.

What’s more — remittances are extremely efficient.

Most top-down channels of money transfer — from foreign investment to aid — get bogged down by bureaucracies and transaction costs. In fact, there’s some evidence that foreign aid can even do more harm than good. It creates a source of ‘easy money’ for governments, which increases corruption and makes them less likely to take up the hard work of reform.

Remittances are the opposite. Because individual people send money home, that money goes to the exact people who require it. People are the most likely to send money home when their families need it the most. Households receiving remittances have a high likelihood of having elderly people, women, or children. Researchers looking at US-Mexico migration found that remittances tend to lower inequality. Over time, In fact, they realized that remittances became more and more pro-poor — as migration went up, poorer and poorer people began heading abroad.

All of this means that remittances have a very real impact on everything from education to health, to hunger.

Remittances are also very resilient. Unlike foreign investments that pull back during crises, for instance, remittance flows are counter-cyclical — they increase when economic conditions worsen.

It’s still hard to send money home

Because of all the many benefits of remittances, it’s particularly tragic that sending money home is rather difficult. Much of the remittance money is actually lost to banks and money transfer companies.

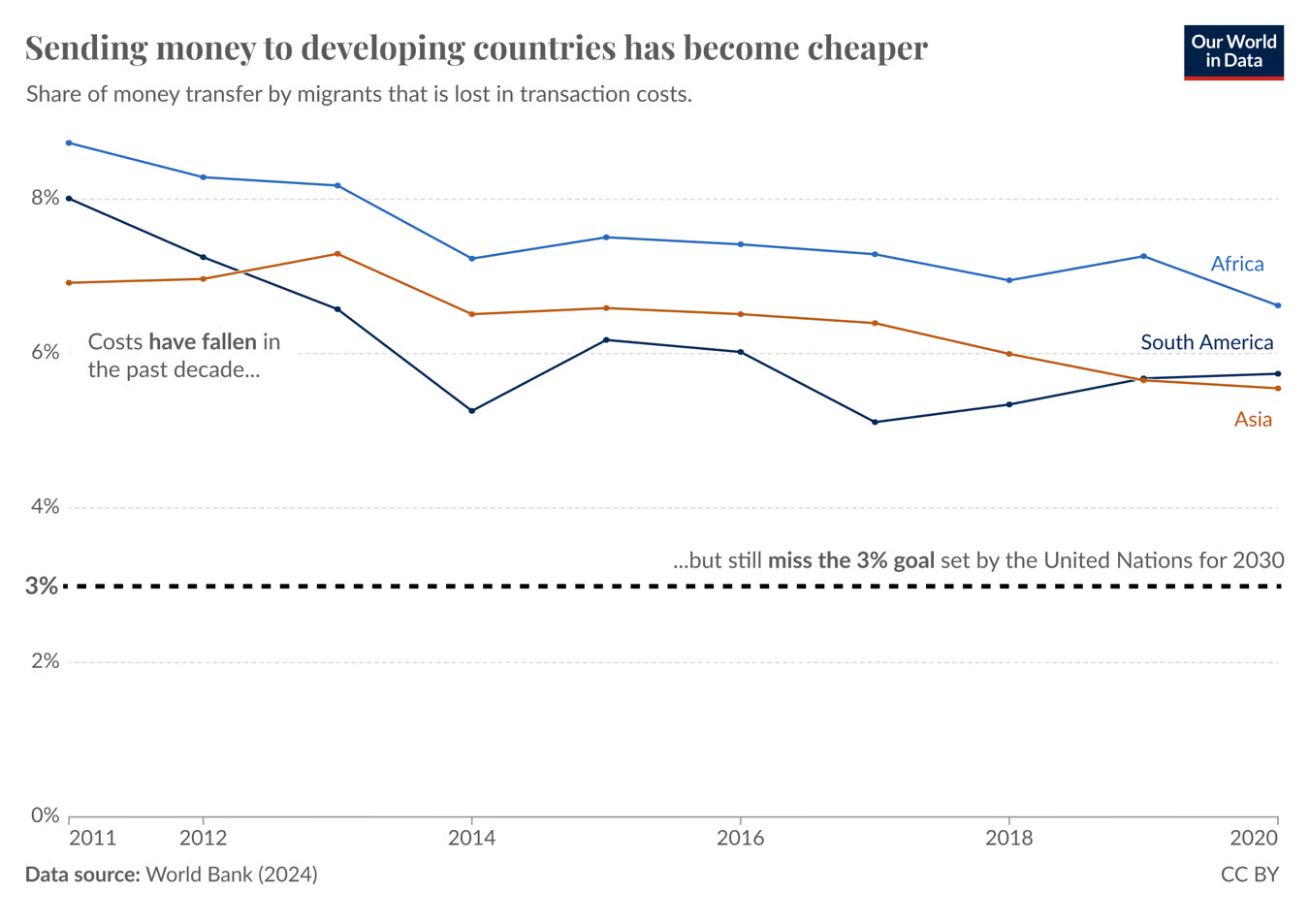

The global average fee for sending remittances is 6%. That is, for every $100 someone sends home, $6 is lost in transit. Things are worse in some parts of the world. In some African corridors, for instance, these transaction costs exceed 8%, with extreme cases hitting 10%. Tragically, these are the poorest parts of the world and need that money the most.

Moreover, the countries that need remittances the most suffer from the worst structural challenges. Their citizens lack access to bank accounts or digital payment options, for instance, forcing them to rely on costly informal channels — like hawala networks.

The United Nations wants to bring the global average cost for remittances to drop down to 3% by 2030. While things are slowly getting there, we’re still nowhere close.

One of the most efficient and under-appreciated routes of spurring development, therefore, could simply lie in making remittances easier. Our World in Data suggests two approaches:

Transparency: Governments can push money-transfer companies to clearly display their fees and exchange rates. This makes migrants’ lives easier, as they can easily figure out the cheapest option available to them. Taking things one step further, countries like Australia and New Zealand have even launched platforms that allow migrants to compare costs across platforms.

Banking integration: Governments can also invest in payment networks that connect the banking systems of different countries. The United States and Mexico tried doing so, for instance — and remittance fees came down to $0.67 per transaction. Such changes can have serious cost implications for migrants.

Not only will these interventions ensure that more money reaches home, but it will also make migrants more likely to try sending money back in the first place. The United Nations believes that if average remittance costs come down to 3%, that could add an extra $32 billion to global remittances.

An untapped growth lever

To tell you the truth, we hadn’t really processed how big remittances are when we started with this story. Remittances always felt like a second thought — behind foreign investments and trade. But the numbers defy this. Remittances are the second largest line item in our external accounts, only behind services exports. At more than $100 billion a year, they dwarf the net FDI coming into India. They practically offset our trade deficit.

In all, they make up ~3.7% of our GDP. For context, that’s approximately the size of India’s financial services industry or our petrochemicals industry. That’s absolutely massive.

Remittances are a reminder that mobilizing capital isn’t just a matter of corporate finances or big institutions. Millions of individuals — making quiet but important contributions to their families and communities — are equally a part of this story. Reducing barriers to these transfers won’t just make transactions cheaper — it could be a big, untapped lever for India’s growth.

Tidbits

Swiggy reported a ₹799 crore net loss in Q3 FY25, widening from ₹574.4 crore last year, driven by higher capex on quick commerce and infrastructure investments. Despite this, revenue surged 31% YoY to ₹3,993 crore, with total consolidated income reaching ₹4,095.8 crore. Adjusted EBITDA losses grew by ₹149 crore, mainly due to ESOP charges and depreciation costs. The company’s B2C Gross Order Value (GOV) grew 38% YoY, reflecting strong consumer demand.

Adani Green Energy Ltd (AGEL) is in talks with Indian banks to raise $2-2.5 billion over the next 6-8 months to ramp up its renewable capacity. The company, which has maintained an annual run rate of 3-4 GW, plans to accelerate additions to 7-8 GW annually to hit its 50 GW target by 2030. A major chunk of this growth will come from Khavda, Gujarat, where capacity is set to rise from 2.4 GW to 30 GW by 2029. In FY24, AGEL added 3 GW, with total capacity expected to close at 5 GW for the year, bringing its portfolio to 12 GW as of December 2024.

The NSE has witnessed a significant slowdown in its derivatives market following Sebi’s regulatory crackdown. The average daily traded volume (ADTV) in equity futures plummeted by 15% to ₹1,71,825 crore, while equity options saw a 7% dip to ₹61,295 crore. These declines reflect the impact of six measures Sebi introduced in October 2024, including reducing weekly expiries from five to one, increasing lot sizes to ₹15-20 lakh from ₹5-10 lakh, and mandating upfront option premia collection.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Pranav

🌱One thing we learned today

Every day, each team member shares something they've learned, not limited to finance. It's our way of trying to be a little less dumb every day. Check it out here

This website won't have a newsletter. However, if you want to be notified about new posts, you can subscribe to the site's RSS feed and read it on apps like Feedly. Even the Substack app supports external RSS feeds and you can read One Thing We Learned Today along with all your other newsletters.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉 Join the discussion on today’s edition here.

Never thought I would read about Remittances from this perspective. Great work🙌

Remittance! Loved it!!! 😊