Global maritime trade is literally the lifeblood of the world economy. Around 80% of all the goods we trade, from oil and iron ore to cars and clothing, move by sea. Every day, huge ships connect producers and consumers across continents.

In this episode of Beyond the Charts, we’re unpacking how this massive system works and how it’s changing, based on insights from the UNCTAD Review of Maritime Transport 2025. We’ll look at what’s driving global shipping today, from shifting trade routes and new technologies to the growing pressures of geopolitics and climate goals, and what all of this means for the future of trade.

Let’s start with the big picture.

Growth amid volatility

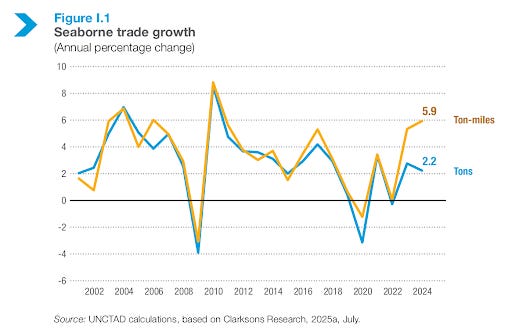

After the pandemic shock, maritime trade has bounced back, but not quite the way it used to. In 2024, global seaborne trade reached 12.7 billion tons, up 2.2% from the year before. That’s slightly above the average growth of the past decade but well below the boom years of the early 2000s. In other words, shipping recovered, but the long-term trend points to slower, more uneven growth. UNCTAD expects trade to rise by just 0.5% in 2025, essentially flat.

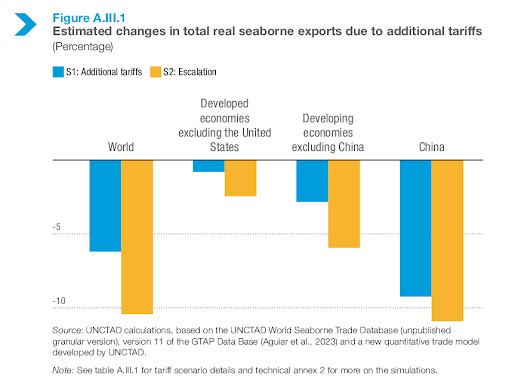

Why the slowdown? Global trade faces a tricky mix of headwinds: weak demand, persistent inflation, and tighter financial conditions. Even the WTO projects that overall merchandise trade will grow barely 0.1% this year.

Beyond short-term shocks, there’s a deeper story: the link between global trade and GDP is weakening. Economies are growing, but each unit of GDP now generates less cross-border trade than before. That’s why shipping volumes aren’t surging even as recoveries take hold.

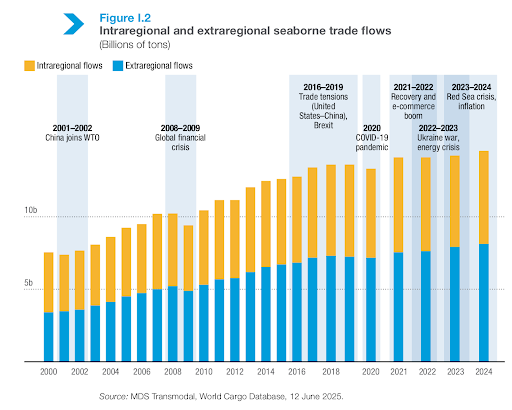

And yet, volatility remains the defining feature. Think about it: trade collapsed in 2020, roared back in 2021, slowed again with the Ukraine war, energy crisis, and inflation in 2022–23, and then was disrupted once more by the Red Sea crisis. These stop-start cycles make life hard for shippers and ports, which swing between capacity crunches and quiet docks.

Here’s a fascinating detail from the UNCTAD report: in 2024, while total trade volume rose 2.2%, shipping output in ton-miles jumped nearly 6%. That means ships were sailing farther on average—a direct effect of longer detours and rerouted trade. So even modest growth in trade can mean much higher demand for shipping if supply chains stretch out. But if routes shorten again, the same ships could suddenly be in excess supply.

For now, those longer voyages are keeping ships busier and freight revenues higher. The question is, what happens when the world’s sea lanes normalize?

Geopolitics redrawing the map of trade

Not since the Suez Canal crisis of the 1960s has the geography of global shipping been this disrupted.

Geopolitical tensions and climate shocks are literally redrawing the world’s sea routes, forcing ships to take longer, costlier detours.

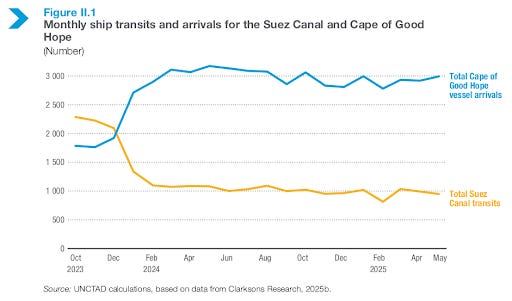

Take the Red Sea. It’s one of the most important arteries of global trade, linking Asia and Europe through the Suez Canal. But since late 2023, escalating conflict around the region has made it too risky for many vessels to pass through. By May 2025, traffic through the Suez Canal had dropped almost 70% from 2023 levels. Instead, ships began sailing thousands of extra miles around Africa’s southern tip—the Cape of Good Hope.

The Panama Canal has faced its own crisis, not from war, but from climate. A historic drought lowered water levels and forced authorities to restrict the number of ships passing through in 2024. Between the Red Sea and Panama disruptions, vessels were suddenly traveling much longer routes, causing massive delays and driving up costs.

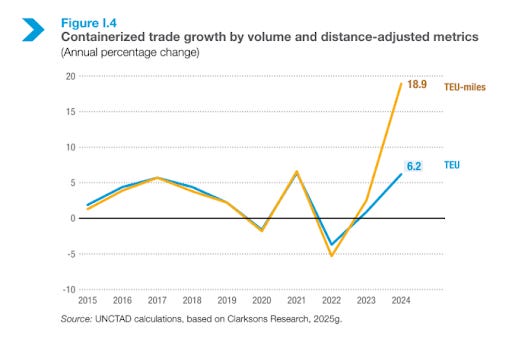

The numbers tell the story. While total trade volume in 2024 grew just 2.2%, total shipping output in ton-miles jumped nearly 6%. Container ships saw an even sharper rise,

up almost 19%.

In short, the same cargo now needed more ships and more sailing time to move. That kept freight markets tight, even without a surge in trade volumes.

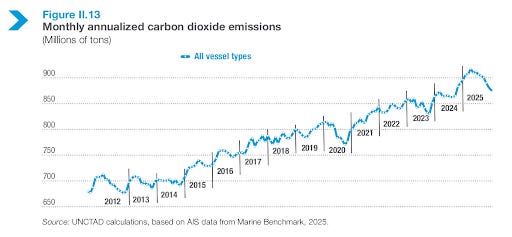

But there’s a trade-off. Longer voyages mean higher fuel and insurance costs, more emissions, and slower deliveries. According to UNCTAD, global shipping emissions rose 5% in 2024, partly because of these extended detours.

And it’s not just the Red Sea or Panama.

The war in Ukraine has completely reshaped energy routes. Russian oil that once flowed to Europe now travels on longer-haul voyages to Asia, while Europe imports oil from the U.S. and the Middle East instead. That “shuffle” has pushed up average voyage distances for tankers.

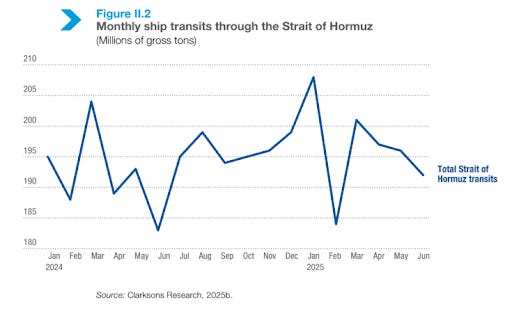

Meanwhile, tensions around the Strait of Hormuz, which handles 11% of world maritime trade and over a third of all seaborne oil, continue to keep the world on edge. The flare-up between Iran and Israel in mid-2025 sent tanker freight rates soaring due to rising war-risk premiums.

Even trade policy is reshaping shipping lanes.

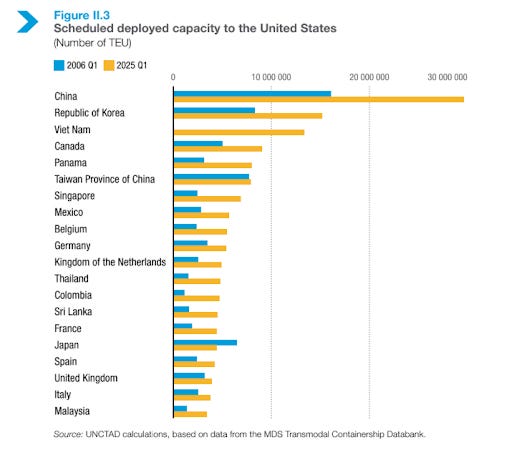

In 2025, the U.S. introduced new tariffs and proposed port fees on certain foreign-built or -operated vessels. These measures are still evolving, but they could change how global fleets are deployed and which ports they frequent.

All this is driving a deeper shift in how supply chains are organized. Companies are diversifying production and sourcing, moving away from over-centralized models. We’re already seeing stronger export growth from Southeast Asia—countries like Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia—as well as from India and Mexico.

ow, it’s important to separate what’s temporary from what’s structural.

Some of these detours, like the Red Sea reroutes, will probably end when security improves. But others may be here to stay. Climate-driven water shortages, like those at the Panama Canal, could become more frequent. And geopolitical rivalries aren’t going anywhere. That means global shipping might have to stay permanently more flexible, adapting to an era of shifting trade corridors.

The impact of all this isn’t shared equally.

For businesses, longer routes mean higher logistics costs and more uncertainty.

For policymakers, it highlights the need for secure trade corridors and better regional connectivity. And for consumers, it often translates into higher prices for imported goods.

But the harshest impact falls on developing countries, especially small island and landlocked nations. As UNCTAD’s foreword puts it:

“Small island developing States watch their import bills soar while their export competitiveness erodes. Landlocked developing countries sometimes pay transport costs three times the global average, and that gap widens with each disruption.”

In other words, the great rerouting of global trade isn’t just a story about ships and canals. It’s a story about how distance, politics, and climate are reshaping the cost of being connected to the world.

Container shipping: Navigating new routes and capacity shifts

If you’ve ever seen those giant ships stacked high with colorful containers, you’ve seen the workhorses of global trade.

Container shipping keeps the world’s supply chains running, moving everything from electronics to furniture to clothing in standardized steel boxes that make global trade possible.

But after a wild few years, this sector is now in the middle of a reset, adapting to new trade routes, new partnerships, and a lot of uncertainty.

Let’s start with how trade routes themselves are changing.

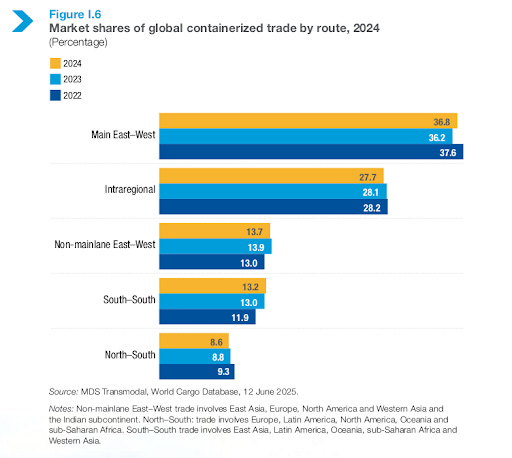

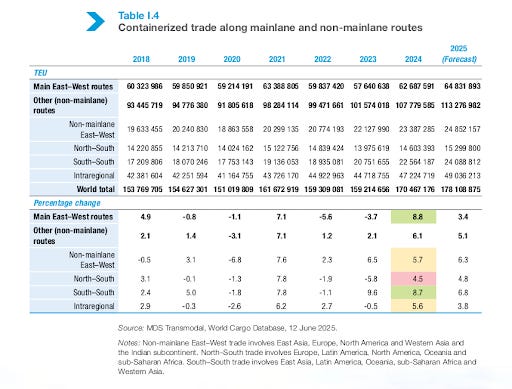

The big East–West corridors, connecting Asia with Europe and North America, still dominate global container traffic. But growth is shifting elsewhere. South–South trade routes like Asia–Africa, Asia–Latin America, and intra-Asia were the most dynamic in 2024. As developing economies industrialize and trade more with one another, we’re seeing more direct shipping links between these regions.

This isn’t just about new markets; it’s also about resilience. Shippers are deliberately diversifying routes and building more flexible supply chains to avoid dependence on any single chokepoint or trade lane. In other words, global trade is learning to hedge against shocks.

Now, the industry side of the story.

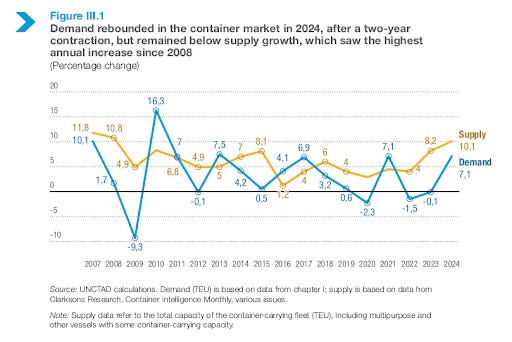

After the pandemic, container lines made record profits as freight rates hit historic highs. From 2021 to 2022, they went through what UNCTAD calls a “cash-flow boom.” Carriers used that windfall to order a wave of new, larger ships.

Those vessels are now being delivered just as demand growth is slowing. In 2024, total container shipping capacity jumped nearly 10%, the biggest annual increase since 2008, raising fears of too many ships chasing too little cargo. When that happens, freight rates usually fall.

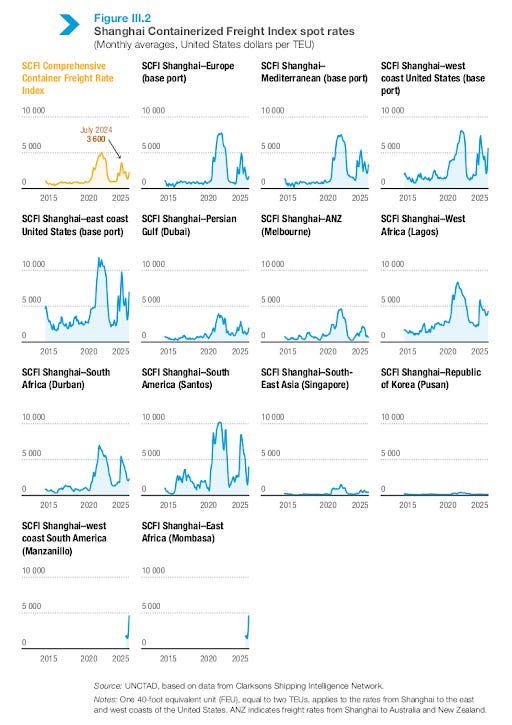

And rates have indeed been swinging wildly.

The Red Sea crisis in early 2024 sent them soaring close to pandemic peaks. By the end of the year, they had cooled, but they stayed well above pre-crisis levels. Then, in the first half of 2025, they spiked again, this time because exporters rushed to ship goods ahead of possible tariff changes and amid rising geopolitical risks.

The report sums it up neatly: trade policy uncertainty, new domestic shipbuilding programs, and shifting alliances are making this one of the most volatile periods in container shipping history.

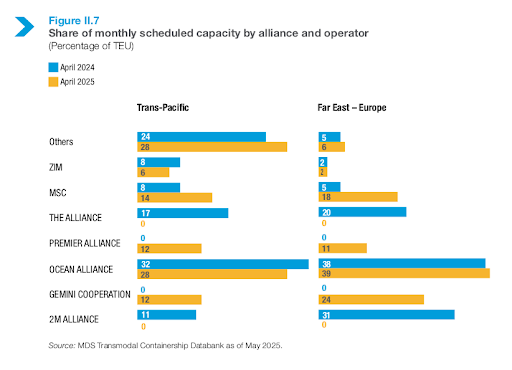

Speaking of alliances, the industry map is being redrawn.

The long-standing 2M alliance between Maersk and MSC ended in 2025. Maersk joined Hapag-Lloyd to form the new Gemini Cooperation, while ONE, HMM, and Yang Ming created the Premier Alliance.

Meanwhile, MSC, now the world’s largest carrier, has decided to go solo.

These new partnerships aim to match capacity with shifting trade flows, but they’re also causing short-term confusion for shippers about routes, schedules, and reliability.

So where does that leave the industry?

The container sector is coming down from the extreme highs of 2021–22 and entering a more balanced but uncertain phase. Fleet capacity is growing faster than trade volumes. Routes are becoming more diverse. Alliances are reshaping.

UNCTAD expects containerized trade to keep expanding, though at a slower pace than fleet growth. For businesses, that could mean lower freight costs than in the boom years, but also more volatility as carriers adjust.

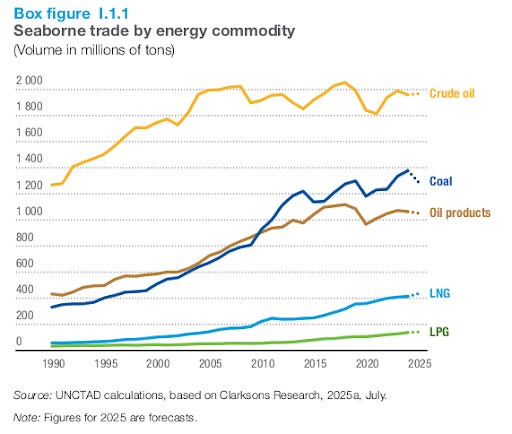

Energy cargoes: fossil fuels down, gas up

The makeup of what the world ships by sea is changing—and nowhere is that more visible than in the energy trade. For decades, bulk energy cargoes like oil and coal dominated maritime shipping. Today, decarbonization goals and geopolitics are reshaping those flows, some changes temporary, others structural.

Let’s start with coal.

Despite the global shift toward cleaner energy, coal remains a heavyweight in dry bulk shipping. In fact, 2024 saw a 3.3% jump in seaborne coal trade, reaching its highest level since 1980. The main reason? Strong demand from Asia—especially China and India—and industrial stockpiling by several importers.

But as UNCTAD points out, this is a “temporary rebound” rather than a comeback. In the long run, coal’s share in maritime trade is flattening out, while gas and cleaner fuels slowly gain ground. The center of gravity has decisively moved eastward: European and North American imports are shrinking, and Asia now dominates both demand and trade routes.

That means longer voyages, for instance, coal shipments from Colombia or Russia traveling farther to reach Asian ports. Yet, even with occasional demand spikes, the broader trend is clear: a gradual decline in coal’s role as climate policies tighten over the coming decade.

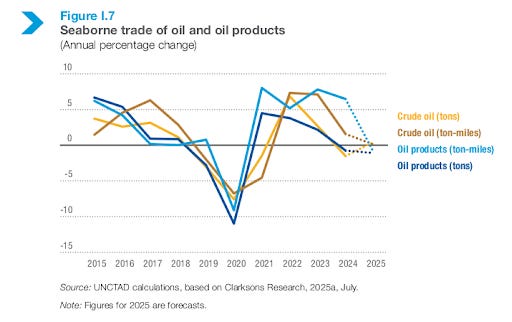

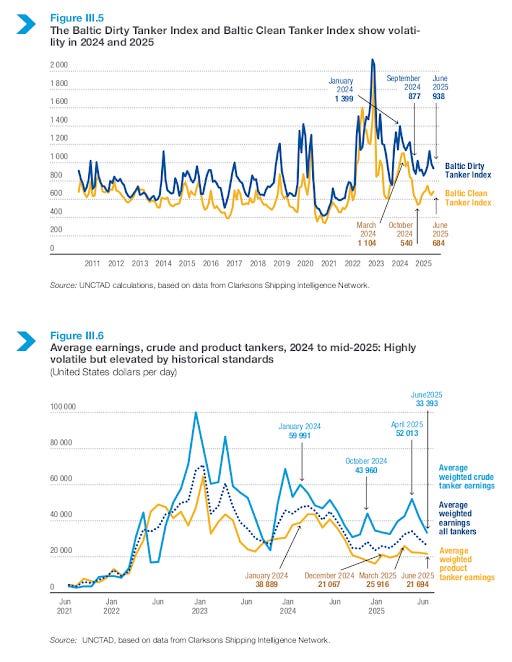

Oil tells a similar story: long-term pressure from the energy transition, but short-term turbulence from geopolitics. In 2024, seaborne crude oil shipments fell by 1.5%, and refined petroleum products slipped 0.7%, extending a pattern of stagnant growth seen since 2010. But interestingly, ton-miles, which measure both cargo and distance, rose: up 1.6% for crude and 6.5% for refined products.

Why? Because the war in Ukraine and related sanctions have forced a massive reshuffling of routes. Europe has cut pipeline imports from Russia and is now buying oil from the U.S. and the Middle East, while Russia sends its barrels east to Asia.

So even though less oil is moving overall, ships are sailing much farther. Tanker markets stayed firm in 2024, not at the wild peaks of 2022–23, but still profitable thanks to those longer hauls. And new players like Brazil and Guyana are emerging as exporters, driving even more long-distance shipments to Asia.

Then there’s liquefied natural gas, or LNG, the most dynamic fossil fuel in maritime trade right now.

Often seen as a “bridge fuel” in the energy transition, LNG has become central to global energy security. In 2024, LNG trade volumes rose 1.1%, but ton-miles surged a massive 12.2%. That means much longer voyages, from Africa and the U.S. to Asia and Europe, as new export terminals came online in both regions.

UNCTAD expects this momentum to continue in 2025 as more liquefaction capacity ramps up. The LNG fleet is growing fast, with a record order book and new routes forming as the U.S. joins Qatar and Australia among the top exporters.

And beyond these fuels?

There’s already talk of hydrogen and ammonia as potential clean-energy cargoes of the future. But for now, UNCTAD notes, they’re more relevant as alternative ship fuels than as major traded commodities.

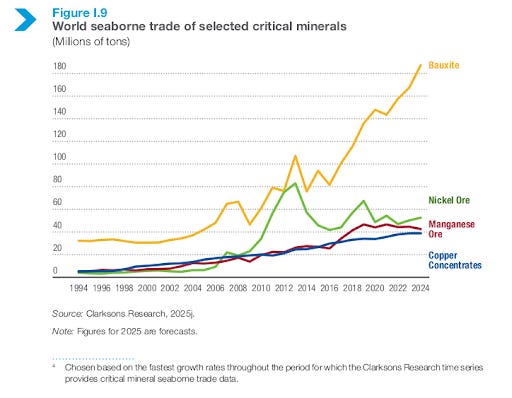

Critical minerals

For most of the 20th century, oil was the world’s “strategic commodity.” In the 21st, a new set of materials is taking that title—critical minerals. These are the metals that power clean energy and high-tech industries; think about lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, and more. They’re what make electric-vehicle batteries, wind turbines, solar panels, and smartphones possible. And as demand for all these products soars, seaborne trade in these minerals has surged, turning ships into the new arteries of the green economy.

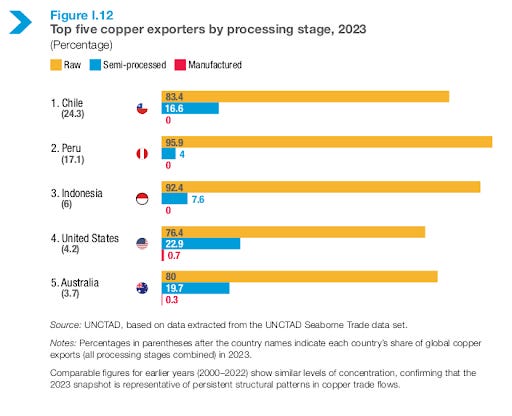

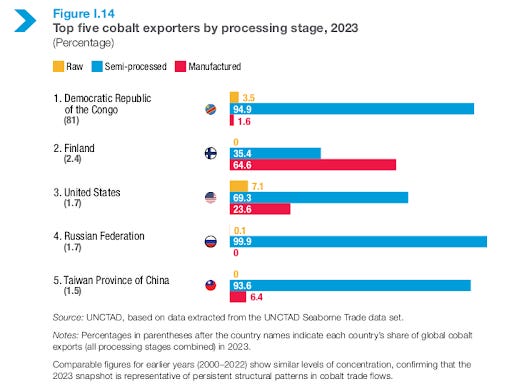

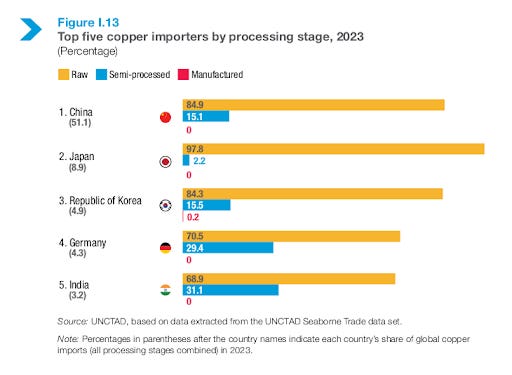

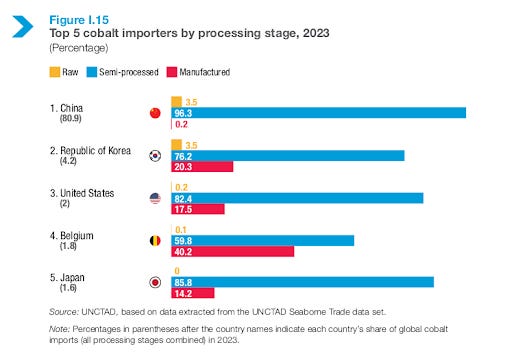

The report calls this one of the defining shifts of our time. Asia, and especially China, has become the central destination for many of these minerals because that’s where most of the processing and manufacturing happens. Meanwhile, Africa, Latin America, and Oceania are the main sources. Think copper from Chile and Peru, cobalt from the DRC, bauxite from Guinea, and nickel ore from Indonesia almost all flowing toward Asia.

But here’s the catch: production and trade are highly concentrated.

The report notes that global trade in critical minerals “remains concentrated in a handful of exporters,” which makes supply chains vulnerable to both political and logistical shocks. One striking example: in 2023, the DRC accounted for more than 80 percent of all seaborne cobalt exports. That level of dependence mirrors the old reliance on a few oil producers decades ago.

Naturally, this has set off a geopolitical scramble. Importing countries are racing to secure supply.

The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act and the EU Critical Raw Materials Act both aim to diversify sources and expand domestic processing. On the other side, resource-rich countries are asserting more control, imposing export restrictions, as Indonesia has done for nickel, or adding local-content rules to keep more value at home.

For maritime trade, this means bigger cargo volumes and new routes. UNCTAD reports steady growth in seaborne shipments of bauxite, nickel ore, manganese ore, and copper concentrates, mostly carried by bulk carriers.

Strategically important lanes now link Africa, Latin America, and Australia with Asia’s industrial centers, above all, China. If you trace copper and cobalt flows on UNCTAD’s maps, Asia clearly sits at the heart of this new network.

Is this shift temporary? Hardly.

UNCTAD’s projections show global demand for these energy-transition minerals could nearly triple by 2030 and quadruple by 2040. That means decades of expansion in mining, processing, and, crucially, shipping.

While recycling and technology might ease the pressure later, the near-term reality is clear: the ocean trade in critical minerals is entering a long-term growth phase. And just like oil once did, these materials are already reshaping alliances, with countries forging new strategic partnerships around minerals to secure their place in the clean-energy supply chain.

Decarbonizing the fleet

Even as ships carry the materials needed for the world’s green transition, the shipping industry itself faces one of its toughest challenges yet: decarbonization.

Maritime transport is incredibly efficient for moving huge amounts of cargo, but because of its sheer scale, it’s still a major emitter. Big ships burn fossil fuels, and the sector accounts for about 3% of all global emissions. UNCTAD calls this “the gap between ambition and reality”, a gap the industry now has to close.

And it’s not getting easier. In 2024, shipping emissions rose about 5%, partly because vessels had to take longer routes and sail faster to meet delivery schedules. Meanwhile, more than 90% of the global fleet still runs on conventional fuels. Only 8% can currently use cleaner alternatives.

To change that, regulators are moving fast. In July 2023, member states of the International Maritime Organization adopted a climate strategy aiming for net-zero emissions from shipping by around 2050, with interim goals for 2030. Then, in April 2025, the IMO’s environment committee approved draft measures under a new Net-Zero Framework, a global system that combines technical and economic tools to drive change.

Here’s how it works:

First, a fuel standard: ships will need to reduce the greenhouse gas intensity of the fuel they use over time.

Second, a pricing mechanism: ships that exceed emissions targets will have to buy “remedial units,” contributing to a new Net-Zero Fund, while cleaner ships could earn rewards. That fund would then help finance innovation, port infrastructure, and a just transition for developing countries.

So, what does a low-carbon future look like at sea?

It won’t be one single fuel or technology, but a mix. LNG is already being used as a transition fuel, making up over a third of all new ship orders in 2024. Methanol is gaining ground quickly, while ammonia and hydrogen are seen as the next generation of zero-emission fuels, though technical and safety hurdles remain. At the same time, efficiency improvements—better hull design, slow steaming, smarter routing, and even wind-assist technologies—are helping ships burn less fuel.

The orderbook shows how fast the industry is pivoting.

As of May 2025, more than half of all ships on order, about 53% by tonnage, are being built to run on alternative fuels. But this creates a “zero-carbon fuel dilemma.” Ships last 20 to 30 years, and no one knows which future fuel, be it ammonia, hydrogen, or something else, will win. That uncertainty makes it challenging for shipowners to commit today.

Existing regulations are also tightening. Since 2023, measures like the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) and the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) have forced ships to meet efficiency benchmarks. Those that don’t must either slow down or retrofit—both of which affect costs and capacity.

And if the IMO’s carbon-pricing plan is approved, operating costs will rise further for high-emission vessels, giving shipowners another reason to go green.

But going green won’t be cheap. UNCTAD estimates annual investment needs between $8 and $28 billion for new or retrofitted ships and an additional $30 to $90 billion a year for onshore infrastructure, things like green-fuel production, storage, and port refueling systems. Many older ships will likely be recycled, converted, or replaced in the coming decade as the fleet turns over.

In short, the decarbonization of shipping is no longer a distant goal; it’s a massive industrial transformation already underway. And while the road to zero-carbon seas will be long and costly, the direction is now set: global shipping is finally starting to clean up the cargo that makes the world go round.

Ports and People

Maritime trade isn’t just about ships and cargo. It’s also about the ports and the people that keep this massive system running. The last few years have stress-tested both, pushing ports to become smarter l and more efficient while also reminding the world just how vital human labor is to global trade.

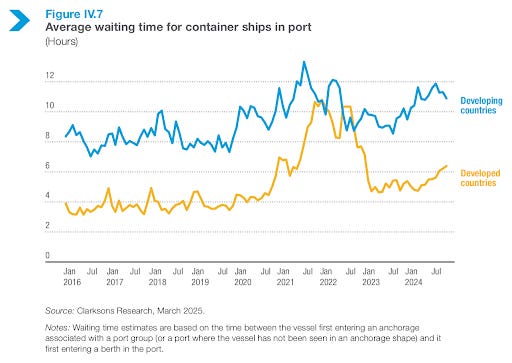

Ports are where sea meets land, and they’ve been under pressure. Even in 2024, congestion was rising. UNCTAD data show that the average vessel waiting time increased from 5.2 to 6.4 hours in developed countries and from 10.2 to 10.9 hours in developing ones. Those few extra hours may not sound like much, but across thousands of ships, they ripple through the entire supply chain, adding costs and delays that businesses and consumers ultimately feel.

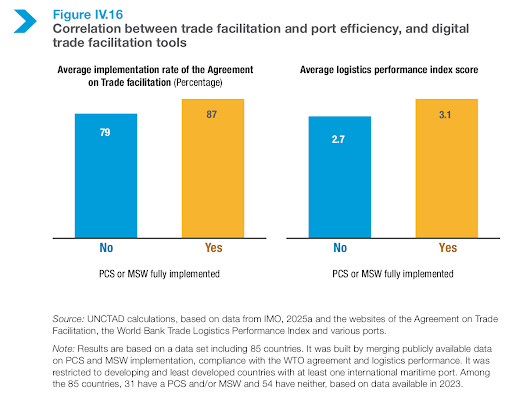

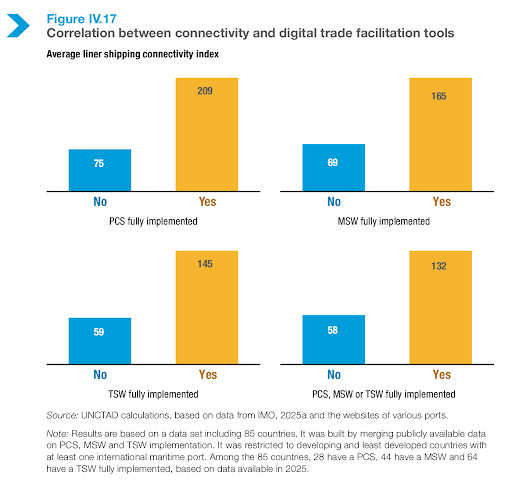

To fix this, ports are going digital. Tools like Maritime Single Windows and Port Community Systems are transforming how information flows—allowing ships, customs, and port authorities to exchange data electronically instead of relying on paper or siloed systems. This means faster cargo clearance, smoother vessel scheduling, and more predictable turnaround times. UNCTAD’s data even show that ports using these systems tend to score higher on logistics and trade facilitation indicators. Automation, from yard cranes to container tracking, is speeding things up even further.

But digitization brings new risks. As ports become more connected, they also become more vulnerable to cyberattacks that can cripple operations.

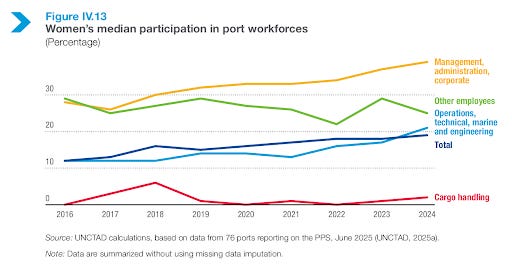

Then there’s the human side of the story. Ports depend on people, and the workforce itself is evolving. There’s been progress on gender diversity; in 2024, women held 39% of management and administrative roles in reporting ports. But in hands-on operational jobs like cargo handling, that figure drops to just 2%. Automation could help change that by making physically demanding roles more accessible, but it’ll take active policy support to close the gap.

At sea, the situation is even more urgent. The industry faces a growing seafarer shortage, worsened by the tough conditions exposed during the pandemic. The report highlights that protecting seafarers’ rights, fair treatment, shore leave, repatriation, and safe working conditions under the Maritime Labor Convention is essential to attract and retain skilled crews. Without them, global trade literally stops.

As automation advances and autonomous ships edge closer to reality, the kinds of maritime jobs will change. Some traditional roles may disappear, but new ones, in technology, data, and remote operations, will emerge. Managing this transition fairly, through training and upskilling, is key to keeping the system both efficient and humane.

Digitalization and human welfare now sit side by side as priorities. “Smart ports” using data, AI, and IoT are becoming the norm, enabling faster, cleaner, and more reliable trade flows. And international frameworks, from the IMO’s Facilitation Convention, which mandates digital port systems, to the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement, are pushing for universal adoption, especially in developing countries that risk being left behind.

Looking ahead

Maritime trade has always been called a barometer of the global economy, sensitive to every breeze or storm. And right now, it’s sailing through both: short-term turbulence and long-term transformation.

The challenge is knowing which is which.

Structural shifts are the deep, lasting changes: a slower pace of global trade, new routes shaped by emerging markets, the reshaping of energy cargoes as the world goes green, the rise of critical minerals, and the twin revolutions of decarbonization and digitalization within shipping itself. These are the forces that will define maritime trade for decades to come. To stay ahead, shipping lines might focus on high-growth routes in the Global South, invest in dual-fuel vessels, or build expertise in moving new cargoes like critical minerals.

Meanwhile, cyclical forces, like geopolitical uncertainty, will keep testing the system. The trick is to stay resilient enough to ride out those waves without losing sight of the horizon. A port might expand and digitize, but it also needs contingency plans for sudden disruptions. A shipping company might enjoy a temporary freight spike, but if it rushes to order too many new vessels, it risks repeating an old mistake and being caught in the next downturn.

Ultimately, maritime trade isn’t just about ships or cargo; it’s about connection. It reflects how economies rise, adapt, and endure through change. If the industry can stay steady through today’s turbulence, it won’t just weather the storm; it’ll help steer global trade toward a more resilient and sustainable future.

That’s it for this edition. Thank you for reading, and do let us know your feedback in the comments.